Introduction

- Page ID

- 174157

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

I’m a writer. I sold my first national magazine article when I was 16. Writing paid most of my college expenses. When my father lost his job during my junior year, it got me a researcher job working for a congressman who was writing a book. A story I wrote as a college “stringer” for the Associated Press appeared in newspapers worldwide, including Hong Kong. It enabled me to win a national collegiate newswriting award. I’ve been writing for money ever since that first magazine article.

I’m also an editor. I didn’t set out to be an editor. I set out to be a reporter. But my bosses, beginning with my very first job, saw in me something that said I had the essential skills needed to plan, organize, and direct coverage of news. So that’s what I’ve done most of my life.

For a bit less than a year, I also wrote editorials. To be honest, I found editorial writing less satisfying than reporting or editing, so I left that part of the journalism trade. But during those few months, I learned how to craft an argument in print to sway peoples’ minds.

Writing is a foundational skill. I challenge you to name one job where being a better communicator wouldn’t be a benefit.

This is a course on writing, specifically writing for public relations. But in many important respects, it is also a course in journalistic writing because the two are very similar. Working as a newspaper reporter or a radio/tv reporter traditionally is an excellent stepping stone to a satisfying career in public relations. It still is.

The difference between the two is largely a matter of whom you serve. In journalistic writing, you write for the broad general public. Some journalists, however, don’t write for the broad general public; instead, they write for a niche market, such as the automobile industry or the beer industry. But they still follow all the rules and principles of journalistic writing.

In public relations writing you are writing on behalf of a client. Usually, you are hoping to get the client’s message in front of members of the broad general public. Sometimes to do that, you have to go through “gatekeepers” – editors who decide whether your message is worthy of being in their publication or on their airwaves, or on their online news publication.

Other times, you may be writing for a publication the client distributes to some or all members of the general public. Many hospitals, for instance, produce quarterly magazines of 16 to 20 pages that feature two or three stories about a patient who had a dread disease or serious injury, was treated at that particular hospital by a particular doctor, who recovered and now is living happily. The hospital’s objective in producing that magazine is get you to be a patient.

In still other cases, you may be writing for an internal audience, usually employees, but in the case of colleges also alumni. The goal when writing for employees is to reinforce the idea that they are working for a fine college. The goal when writing for alumni is to maintain the bond between the college and the student that existed when the alum was a student. If that bond is maintained, the college expects three things will happen:

--First, the alum will encourage young people to attend his college, so it becomes a “free” marketing effort.

--Second, the alum will make donations to the college over time. Sometimes these donations can be substantial. An Associated Press reporter upon his retirement made a $1 million commitment to the journalism program from which he got his start 40 years earlier.

--And third, the college expects the alum will come back to campus for football, basketball, softball, soccer or any one of a multitude of other sports.

In all cases, the key to success is writing. To put it quite bluntly, if you cannot write, and write well under pressure, your prospects in either journalism or public relations are substantially diminished.

But how do you learn how to write? Fundamentally, writers write. They write a lot. They read books about writing. In short, they work at writing and at becoming better writers. That’s where a course like this is useful even to an experienced writer. I have never taken a writing course or writing workshop that I haven’t learned something new or been reminded of something I learned but forgot long ago.

For someone who is not an experienced writer, a course such as this gives you the basic framework in which to begin to develop your skills.

The second things writers do is read. They read a lot. They read different genres. But especially they read fiction and nonfiction works in the area in which they focus. If you were a journalist on Dec. 7, 1941, the morning when Japanese bombers attacked Pearl Harbor, how would you report the news? Read how the Associated Press reported the attack:

AP WAS THERE: 75 years ago, the AP reported on Pearl Harbor

A couple of explanatory comments: A “Flash” is rarely used by news services. It is intended to alert editors to news of extraordinary importance. In 1941, when AP stories were distributed by teletype machines, it would have been preceded by the sound of eight bells ringing, followed by eight bells.

A “Bulletin” is also rare, but not nearly as rare as a Flash. A Bulletin is used to communicate breaking news of major importance. When a flash is issued, it is immediately followed by a bulletin, as in the example above.

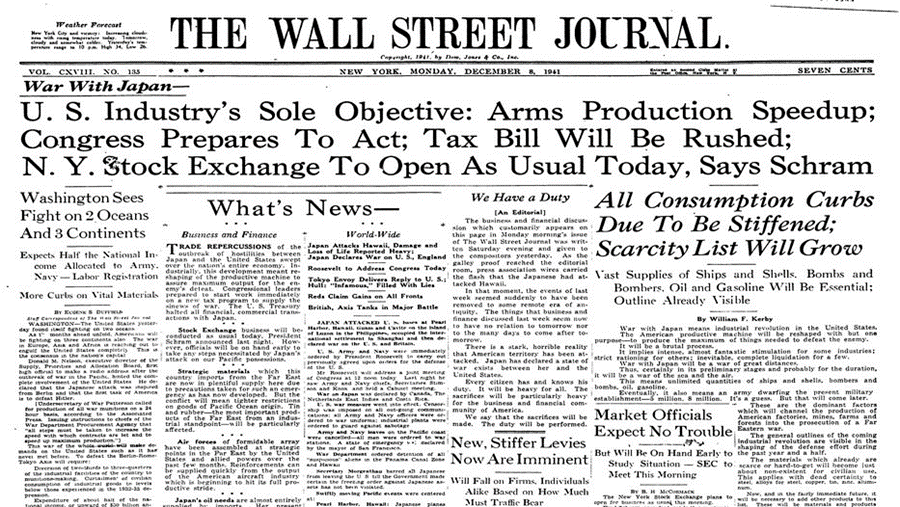

The result of the attack would be a transformation of American society. Here’s the front page of The Wall Street Journal the next morning:

Here’s a link to one of the two lead stories that morning which made clear “the war in Europe, Asia and Africa,” which had been raging since 1938, “is reaching out to engulf the United States completely.”

Washington Sees Fight on 2 Oceans and 3 Continents

Notice in both the AP reporting and the WSJ reporting how clear and concise the information is. (To read the Wall Street Journal story, you’ll need a subscription. Student subscriptions are $4 a month and come with a bunch of extra benefits. Details are here.)

And here’s a link to The Washington Post front page the day after the attack.

The essence of journalistic writing is to focus on what’s important, to write, to use short sentences and simple words (which usually are simpler), and short paragraphs. Journalists and public relations professionals overwhelmingly use AP Style. Why? Because it enables you to tell your story quickly and concisely.

That’s what you’ll learn in this course. How to tell your story quickly and concisely.