17.5: Urban Problems and Policy

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 57124

- Boundless

- Boundless

Suburbanization

Suburbanization is a term used to describe the growth of areas on the fringes of major cities.

Learning Objectives

Analyze the various push and pull factors that lead to suburbanization, including the concept of white flight, as well as the impact of suburbanization on urban areas

Key Points

- In the mid-twentieth century United States, suburbanization was caused by federal governmental incentives to encourage suburban growth and a phenomenon dubbed ” white flight ” where white residents sought to distance themselves from racial minorities in urban areas.

- Push factors are those that push people out of urban areas while pull factors are those that entice individuals to leave urban zones for the suburbs.

- Pull factors are those that attract people to suburbs in particular (like more land or bigger homes).

- White flight refers to the large-scale migration of whites from racially mixed urban regions to more racially homogenous suburban areas.

Key Terms

- Interstate Highway System: The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways (commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, Interstate Freeway System or the Interstate) is a network of limited-access roads, including freeways, highways, and expressways, forming part of the National Highway System of the United States.

- white flight: The large-scale migration of whites of various European ancestries, from racially mixed urban regions to more racially homogeneous suburban areas.

- Redlining: Redlining is the practice of increasing the cost of services such as banking and insurance or denying access to jobs, health care, or even supermarkets to residents in particular areas.

Suburbanization is a term used to describe the growth of areas on the fringes of major cities. Sudden and extreme relocation out of urban areas into the suburbs is one of the many causes of urban sprawl, as suburbs grow to accommodate the increasingly large population. Many residents of suburbs still work within the central urban area, choosing instead to live in the suburbs and commute to work.

Suburbanization is caused by many factors that are typically classified into push and pull factors. Push factors are those that push people out of their original homes in urban areas into suburban areas. Pull factors are those that attract people to suburbs in particular. The main push factors in encouraging suburbanization have to do with individuals feeling tired of city life and the perception that urban areas are overpopulated, over-polluted, and dirty. Further, the mid-twentieth century movement of “white flight” significantly contributed to the rise of suburbs in the United States. The term refers to the large-scale migration of whites from racially mixed urban regions to more racially homogenous suburban areas. White flight began in earnest in the United States following World War II and continues, though in less overt ways, today.

For many of the families that fled the city in favor of the suburbs, the catalyst was the perception of racially diverse urban areas as lower-class and crime-ridden. Real estate law at the time enabled this process, as many minorities were legally excluded from purchasing properties in suburban areas. These racist practices, called redlining, barred African-Americans from pursuing home ownership, even when they could afford it. Suburban expansion was reserved for middle-class white people, facilitated by increasing wages in the postwar economy and by federally guaranteed mortgages that were only available to whites because of redlining. African-Americans and other minorities were relegated to a state of permanent rentership.

The effects of white flight are still seen today. Take, for example, the case of St. Louis, Missouri. St. Louis is a city surrounded by suburbs that are clumped together as the county of St. Louis. St. Louis County developed as whites fled the city for the suburbs. The racial makeup of the city St. Louis and St. Louis County still reflect the racial component of the county’s origins. According to the 2010 United States Census, the city of St. Louis is 49.2 percent African-American, 43.9 percent Caucasian, 3.5 percent Hispanic, 2.9 percent Asian, and 0.3 percent Native American. By comparison, St. Louis County is 70.3 percent Caucasian, 23.3 percent African American, 3.5 percent Asian, 2.5 percent Hispanic, and 0.03 percent Pacific Islander. At the turn of the century, the racial disparities were even more exaggerated.

Pull factors for suburbanization at the turn of the century included more open spaces, the perception of being closer to nature, and lower suburban house prices and property taxes in comparison to cities. Certain infrastructure changes encouraged families to leave urban areas for suburban ones, primarily the development of the Interstate Highway System and insurance policies favoring suburban areas. Following World War II, President Dwight D. Eisenhower launched an initiative to create federal highways to allow for expansion outside of urban areas. Thus, the interstate highway project of the 1950s was developed with suburbanization in mind. Additionally, the government agreed to underwrite mortgages for suburban one-family homes. In effect, the government was encouraging the transfer of the middle-class population out of the inner city and into the suburbs. This movement is thought to have exacerbated urban decline in cities. Insurance companies also fueled the push out of cities and the growth of suburbs, as it redlined many inner-city neighborhoods. This means that insurance companies would refuse to grant mortgage loans to families seeking housing in urban areas and would instead offer lower rates in suburban areas; combined with the federal loans for single-family suburban homes, one sees a joint enterprise between both public and private entities to encourage suburbanization.

The mass movement of families from urban to suburban areas has had a serious economic impact with changes in infrastructure, industry, real estate development costs, fiscal policies, and more. As a result of the mass residential migration out of urban centers, many industries have followed suit. Companies are increasingly looking to build industrial parks in less populated areas, largely to match the desires of employees to work in more spacious areas closer to their suburban homes. “Making it to the suburbs” has become a modern iteration of the American dream. As residential wealth and corporations continue to leave urban zones in favor of suburban areas, the risk of urban decline increases.

Disinvestment and Deindustrialization

Deindustrialization refers to the process of social and economic change ignited by the removal or reduction of industrial activity.

Learning Objectives

Examine the four elements of deindustrialization and its impact on society, in terms of economic restructuring and societal crisis

Key Points

- Deindustrialization is primarily caused by offshoring and shifts toward service sector economies.

- Deindustrialization can have serious socioeconomic consequences in urban areas that used to be reliant on the manufacturing industry for jobs.

- The shift to a service sector economy is called economic restructuring.

- Real industrial production rose in the United States in every year from 1983 to 2007. However, the number of American workers in the manufacturing industry has declined steadily from its peak of 31.5 million in 2000.

Key Terms

- economic restructuring: Economic restructuring refers to the phenomenon of shifting between two types of economies, such as from a manufacturing to service economy or agricultural to manufacturing economy.

- balance of trade deficit: A situation in which a country imports more manufactured products than it exports.

- Foreign direct investment: Foreign direct investment is investment directly into production in a country by a company located in another country, either by buying a company in the target country or by expanding operations of an existing business in that country.

Deindustrialization refers to the process of social and economic change ignited by the removal or reduction of industrial activity/capacity in an area that was formerly supported by the manufacturing industry. Deindustrialization is limited to recent historical moments. It is the inverse process of industrialization —the process of social and economic change that began in the eighteenth century, transforming agrarian societies into industrial ones.

Characteristics of Deindustrialization

Deindustrialization is marked by some combination of four elements.

First, a straightforward decline in the output of manufactured goods or in employment in the manufacturing sector may indicate deindustrialization. However, not every simple decline in output or employment of the manufacturing sector necessarily indicates deindustrialization; short-run downturns may be part of the economic cycle and should not be mistaken for long-term deindustrialization.

Second, deindustrialization may be indicated by a shift from manufacturing to the service sector— economic sectors that focus on serving others rather than producing some physical object. Service sector jobs are seen in government, telecommunication, healthcare, banking, education, legal services, tourism, real estate, or consulting. This shift towards service sector employment would result a shrinking manufacturing sector.

Third, deindustrialization can be marked by a balance of trade deficit, or a situation in which a country imports more manufactured products than it exports.

Finally, deindustrialization can be observed when a nation’s balance of trade deficit is so sustained that the country is unable to pay for the necessary imports of materials needed to further produce goods, initiating a downward spiral of economic decline.

Economic Progress

How is it that economies find themselves in situations of deindustrialization? One explanation centers on economic progress. As economies that were once industrial improve their methods through technological innovation, businesses will find ways to increase productivity or product growth while decreasing the amount of resources they need to devote to production. One “resource” that is particularly expensive is labor. With better technology, employers are able to produce at least the same amount of their product with fewer employees. The decline in employment in manufacturing sectors that comes about from this progress can indicate deindustrialization.

Economic Resturcturing

Another explanation focuses on economic restructuring—institutional and governmental encouragement of the development of a more robust service sector, often at the expense of the manufacturing sector. As the service sector has developed, more and more manufacturing plants have shifted their operations overseas in a process called offshoring. American companies are still involved in the financial aspects of the company; the company remains an American property or American financiers invest through foreign direct investment in companies based abroad. In this model, daily operation occurs overseas, including the hiring of foreign workers in the country where the manufacturing operations are now based. Offshoring demonstrates the importance of scale when considering the process of deindustrialization. While moving a company from the United States to India might result in deindustrialization in America, it does nothing to diminish industry globally. Rather, it redistributes industrialization to India. As such, deindustrialization can be seen as a redistribution of industrial capacity and development rather than a simple decline.

Deindustrialization as a Crisis

When one limits one’s view to a national context, deindustrialization is seen as a crisis. The fact that global industrial capacity has merely been redistributed is little comfort when jobs are being lost at home. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), real industrial production rose in the United States in every year from 1983 to 2007. However, people commonly refer to the United States being in caught in a deindustrialization crisis; growth has slowed and more countries have moved their operations overseas. The number of American workers in the manufacturing industry has declined steadily from its peak of 31.5 million in 2000.

The city of Detroit represents the deindustrialization crisis in the American context. After free-trade agreements were instituted with less-developed nations in the 1980s and 1990s, Detroit-based auto manufacturers relocated their production facilities to other countries with lower wages and work standards. This process took a heavy toll on an auto industry, which was already losing jobs due to technological innovations that required less manual labor. Detroit was once a center of production associated with a high-quality, middle-class standard of living. Today, Detroit is associated with a high concentration of poverty, unemployment, noticeable racial isolation, and a deserted urban center. Deindustrialization can have strongly negative effects in urban areas that were formerly heavily reliant upon the manufacturing sector.

The Potential of Urban Revitalization

Urban revitalization involves redeveloping blighted urban areas for new uses.

Learning Objectives

Examine the postwar development of urban revitalization, specifically related to Title I of the Housing Act of 1949

Key Points

- Urban revitalization has been around since European city planners in the nineteenth century began to consider how to reorganize overpopulated urban areas.

- Title I of the Housing Act of 1949 kick-started the urban renewal program that would reshape American cities.

- Urban renewal can have many positive effects, including better quality housing, reduced sprawl, increased economic competitiveness, improved cultural and social amenities, and improved safety.

- The government has only had mixed success in actually restoring urban areas and has tried to rebrand urban renewal as community redevelopment.

Key Terms

- eminent domain: (US) The right of a government over the lands within its jurisdiction. Usually invoked to compel land owners to sell their property in preparation for a major construction project, such as a freeway.

- Housing Act of 1949: The American Housing Act of 1949 was a landmark, sweeping expansion of the federal role in mortgage insurance and issuance and the construction of public housing. It was part of Harry Truman’s program of domestic legislation, the Fair Deal.

Urban revitalization is hailed by many as a solution to the problems of urban decline by, as the term suggests, revitalizing decaying urban areas. Urban revitalization is closely related to processes of urban renewal, or programs of land redevelopment in areas of moderate- to high-density urban land use. Urban revitalization has been around since European city planners in the nineteenth century began to consider how to reorganize overpopulated urban areas. However, the modern instantiation of urban revitalization is very much a product of the post-World War II economic and social environment. With the influx of money following World War II, the federal government spotlighted American urban areas as the object of renovation.

Most of the postwar development was focused on suburbanization, but urban revitalization was a statutory corollary to suburban development. Title I of the Housing Act of 1949 kick-started the urban renewal program that would reshape American cities. The Act provided federal funding to cities to cover the cost of acquiring declining areas of cities perceived to be slums. According to the act, the federal government paid two-thirds of the cost of acquiring the site, called “the write down,” while the local governments paid for the remaining one-third. Most of the money went towards purchasing the property from the present owners. This process is called ” eminent domain,” or the process through which the government acquires private property for the larger public good. The process of eminent domain requires that the government provide due compensation but does not necessarily require the private property owner’s consent. In the post-war era, after acquiring the properties, the government gave much of the land to private developers to construct new urban housing. These federal incentives to revitalize declining urban areas were particularly attractive to cities that were in states of economic decline at the time.

Urban revitalization certainly provides potential for future urban growth, though the story of successes and failures remains mixed so far. Urban renewal can have many positive effects. Replenished housing stock might signify an improvement in quality; urban renewal may increase density and reduce sprawl, and it might have economic benefits that improve the economic competitiveness of the city’s center. It can also improve cultural and social amenities, through the construction of public spaces and community centers, and can improve safety.

Urban Gentrification

Gentrification occurs when wealthier people buy or rent property in a low-income or working class neighborhood, displacing residents.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the process of gentrification based on three models – demographic, sociocultural and political/economy

Key Points

- While gentrification can bring about higher tax revenues from higher property values, gentrification also dislocates pre-gentrification residents by raising rents beyond their price ranges.

- Gentrification has encountered backlash from the original residents of a community, many of whom organize to fight against the white and wealthy incoming population.

- Several explanations for gentrification exist, including a demographic-ecological model, a sociocultural model, and a political economic model.

Key Terms

- baby boomer generation: The baby boomer generation, or those born during the spike in births in the twenty years following World War II, is starting to reach senior citizenship, and will soon pull from the public funds of Social Security and Medicare.

- urban pioneers: In the 1970s, the first few suburban transplants were called urban pioneers and demonstrated that cities were actually appropriate and viable places to live.

- gentrification: The process of renewal and rebuilding accompanying the influx of middle class or affluent people into deteriorating areas that often displaces earlier usually poorer residents.

Gentrification has gained attention over the last 50 years, as sociologists attempt to explain the influx of middle-class people to cities and neighborhoods and the displacement of lower-class working residents. Gentrification occurs when wealthier people buy or rent property in low- income or working class neighborhoods, driving up property values and rent. While it brings money into blighted urban areas, it often comes at the expense of poorer, pre-gentrification residents who cannot afford increased rents and property taxes.

How to Gentrify Your Neighborhood – A Video Parody: This comedy video raises many critiques of gentrification by parodying the gentrification of Brooklyn, NY. Many critics of gentrification point to its effects on racial composition of the neighborhood as low-income residents are displaced.

The first urban pioneers in a gentrifying neighborhood may have lower incomes, but possess the cultural capital (e.g., education) characteristic of suburban residents. They are often socially and professionally dominant while economically marginalized. Partially due to their age and low-incomes, these individuals frequently reside in households with roommates and are more tolerant of the perceived evils of the city, such as crime, poor schools, and insufficient public services. Thus, they are willing to move into marginal neighborhoods. When the number of urban pioneers reaches such a critical mass, it attracts business investment and new amenities such as bars, restaurants, and art galleries. Once the urban pioneers and businesses have taken the financial risk out of the community, risk-averse investors and residents may enter the newly gentrified neighborhood. Renewed business attracts more investment capital and new residents, increasing local property values. Ironically, upon full gentrification, the urban pioneers are frequently evicted as rents and taxes rise, and the young, poor professionals can no longer afford to live in the area.

Gentrification is often resisted by those displaced by rising rents. However, while protests have an economic dimension, claims are usually articulated as a loss of culture or dismay over the homogenization and flattening of a formerly diverse neighborhood: gentrification generally increases the proportion of young, white, middle- to upper-income residents.

Explanations of Gentrification

Demographic

The demographic explanation emphasizes the impact of the baby boomer generation, born after World War II. In the 1970s, this led to a spike in the young adult population, increasing demand for housing. To meet the demand, urban areas had to be “recycled,” or gentrified. The new baby boomer residents departed from the suburban family idea, marrying later and having fewer children; women in the baby boomer generation were the first to enter the workforce in serious numbers. New urban residents were composed of higher, dual-income couples without children, less concerned about space for large families—one of the main draws to the suburbs for their parents. Instead, they were interested in living in cities close to their careers and enjoying the amenities their higher incomes could afford.

Sociocultural

The sociocultural explanation is based on the assumption that values and beliefs influence behavior. It focuses on the changing lifestyles and values of the middle- and upper-classes in the 1970s. At this time, the suburban ideal was falling out of favor; fewer people were moving to suburbs and more were moving back to cities. These first few suburban transplants, or urban pioneers, demonstrated that cities were viable places to live and began developing a type of inner-city chic that was attractive to other baby boomers, which in turn brought an influx of young affluence to inner cities.

Political Economy

Political economic explanations argue new economic or policy incentives contribute to gentrification. In part, the changing political climate of the 1950s and 1960s produced new civil rights legislation, such as anti-discrimination laws in housing and employment and desegregation laws. These policies enabled black families to move out of urban centers and into the suburbs, thus decreasing the availability of suburban land, while integrationist policies encouraged white movement into traditionally black urban areas.

An alternative explanation suggests that developers and government encouraged gentrification with an eye toward profit. Gentrification may be driven by governments hoping to raise property values and increase revenue from taxes. It may be the result of fluctuating relationships between capital investments and the production of urban space. During the two decades following World War II, low rents in the city’s periphery encouraged suburban development; as capital investment moved to suburbs, inner-city property values fell. Developers were able to see that they could purchase the devalued urban land, redevelop the properties, and turn a profit.

Shrinking Cities and Counter-Urbanization

Counterurbanization is movement away from cities, including suburbanization, exurbanization, or movement to rural areas.

Learning Objectives

Analyze the reasons for suburbanization and counterurbanization, specifically white flight

Key Points

- White flight is one explanation for widespread counterurbanization in the post-WWII era in the U.S. It refers to the movement of middle and upper- class whites to suburbs to avoid living in areas with high proportions of racial minorities.

- Counterurbanization can lead to shrinking cities. Cities with declining populations experience economic strains as infrastructure exceeds the needs of a shrinking population and costs more per capita than during the city’s peak.

- Several approaches have been employed in attempts to address the problems of shrinking cities. Often these approaches aim to increase urban density.

Key Terms

- exurbanization: Exurbanization refers to the process in the 1990s when upper class city dwellers moved out of the city, beyond the suburbs, to live in high-end housing in the countryside.

- urban decay: Urban decay is a process whereby a city, or part of a city, falls into disrepair and decrepitude.

- white flight: The large-scale migration of whites of various European ancestries, from racially mixed urban regions to more racially homogeneous suburban areas.

Suburbanization and Counterurbanization

Recently, in developed countries, sociologists have observed suburbanization and counterurbanization, or movement away from cities, which may be driven by transportation infrastructure or social factors like racism. In developing countries, urbanization is characterized by large-scale movements of people from the countryside into cities. In developed countries, people are able to move out of cities while maintaining many of the advantages of city life because improved communications and means of transportation. In fact, counterurbanization appears most common among the middle and upper classes who can afford to buy their own homes.

White Flight

Sociologists have posited many explanations for counterurbanization, but one of the most debated known as “white flight. ” The term “white flight” was coined in the mid-twentieth century to describe suburbanization and the large-scale migration of whites of various European ancestries from racially mixed urban regions to more racially homogeneous suburban regions. During the first half of the twentieth century, discriminatory housing policies often prevented blacks from moving to suburbs; banks and federal policy made it difficult for blacks to get the mortgages they needed to buy houses, and communities used restrictive housing covenants to exclude minorities.

White flight during the post-war period contributed to urban decay, a process whereby a city, or part of a city, falls into disrepair and decrepitude. Symptoms of urban decay include depopulation, abandoned buildings, high unemployment, crime, and a desolate, inhospitable landscape. White flight contributed to the draining of cities’ tax bases when middle-class people left. Urban decay was caused in part by the loss of industrial and manufacturing jobs as they moved into rural areas or overseas, where labor was cheaper.

Suburbanization

In the United States, suburbanization began in earnest after World War Two, when soldiers returned from war and received generous government support to finance new homes. These young men were also interested in settling down, buying their own homes, and achieving independence and a less hectic daily life with a more affordable cost of living than they could find in cities. Thus, suburbs were built—smaller cities located on the edges of a larger city, which often include residential neighborhoods for those working in the area. Suburbs grew dramatically in the 1950s when the U.S. Interstate Highway System was built and automobiles became affordable for middle class families.

Exurbanization

Around 1990, another trend emerged, called exurbanization: upper class city dwellers moved out of the city, beyond the suburbs, to live in high-end housing in the countryside. This exurbanization may be a new urban form. Rather than densely populated centers, cities may become more spread out, composed of many interconnected smaller towns. The history of counterurbanization calls into question depictions of urbanization as a one-way process. The modern U.S. experience has followed a circular pattern over the last 150 years, from a largely rural country, to a highly urban country, to a country with significant suburban populations.

Shrinking Cities

Whatever its causes, counterurbanization has had serious effects on cities. As a result of counterurbanization, some cities are now losing population. These shrinking cities may face serious problems as they attempt to maintain infrastructure built for a much larger population. As cities shrink, residents must contribute more per capita to maintain fixed infrastructure costs (e.g., for roads, sewers, and public transportation). Dispersed neighborhoods that characterize shrinking cities are also a major source of fiscal distress. These cities must still provide services like fire protection and trash pickup to fewer and fewer citizens over a larger geographic distance, raising the per capita cost.

Several approaches have been employed in attempts to address these problems. Often these approaches aim to increase urban density. For example, planners may revitalize core areas, like downtown, to make them more attractive to businesses and residents. Other cities have tried setting an urban growth boundary to limit sprawl, which increases density within the boundary. The boundary generally encompasses the city and its surrounding suburbs, requiring the entire area to work together to prevent urban shrinkage. This method is being used successfully in many cities (such as Portland, Oregon) to maximize returns on infrastructure investments.

Contributors and Attributions

- Curation and Revision. by: Boundless.com. CC BY-SA

CC licensed content, Specific attribution

- Suburbanization. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Suburbanization)

- St.nLouis. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Louis%23Demographics)

- White flight. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/White_flight)

- St.nLouis County, Missouri. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Louis_County,_Missouri%23Demographics)

- Redlining. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Redlining)

- Interstate Highway System. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Interstate%20Highway%20System)

- white flight. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/white%20flight)

- Industrialisation. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrialisation)

- Deindustrialization. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Deindustrialization)

- economic restructuring. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/economic%20restructuring)

- Boundless. (CC BY-SA; Boundless Learning via www.boundless.com//sociology/definition/balance-of-trade-deficit)

- Foreign direct investment. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Foreign%20direct%20investment)

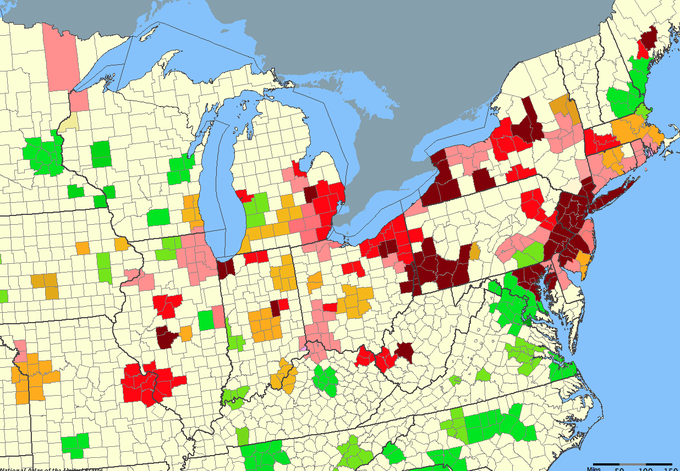

- Rust Belt. (Public Domain; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Rust_Belt)

- Deindustrialization. (Public Domain; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Deindustrialization)

- Berman v. Parker. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Berman_v._Parker)

- Urban renewal. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Urban_renewal)

- Housing Act of 1949. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Housing%20Act%20of%201949)

- eminent domain. (CC BY-SA; Wiktionary via en.wiktionary.org/wiki/eminent_domain)

- Rust Belt. (Public Domain; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Rust_Belt)

- Deindustrialization. (Public Domain; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Deindustrialization)

- Urban renewal. (Public Domain; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Urban_renewal)

- Gentrification. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Gentrification)

- gentrification. (CC BY-SA; Wiktionary via en.wiktionary.org/wiki/gentrification)

- Boundless. (CC BY-SA; Boundless Learning via www.boundless.com//sociology/definition/urban-pioneers)

- Boundless. (CC BY-SA; Boundless Learning via www.boundless.com//sociology/definition/baby-boomer-generation)

- Rust Belt. (Public Domain; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Rust_Belt)

- Deindustrialization. (Public Domain; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Deindustrialization)

- Urban renewal. (Public Domain; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Urban_renewal)

- Gentrification. (Public Domain; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Gentrification)

- How to Gentrify Your Neighborhood - A Video Parody. at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nc2Uv0wEUWs. Public Domain. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Shrinking cities. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Shrinking_cities)

- Counter urbanization. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Counter_urbanization)

- white flight. (CC BY-SA; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/white%20flight)

- Boundless. (CC BY-SA; Boundless Learning via www.boundless.com//sociology/definition/urban-decay)

- Boundless. (CC BY-SA; Boundless Learning via www.boundless.com//sociology/definition/exurbanization)

- Rust Belt. (Public Domain; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Rust_Belt)

- Deindustrialization. (Public Domain; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Deindustrialization)

- Urban renewal. (Public Domain; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Urban_renewal)

- Gentrification. (Public Domain; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Gentrification)

- How to Gentrify Your Neighborhood - A Video Parody. at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nc2Uv0wEUWs. Public Domain. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Baltimore, Maryland. (Public Domain; Wikipedia via en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Baltimore,_Maryland)