2.3 Intersectionality

- Page ID

- 155419

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)"Intersectionality is not just a form of inquiry and critical analysis but it is also a form of praxis that challenges inequalities and opens a collective space for both recognizing common threads across complex experiences of injustice and responding to them politically" (Ferree, 2018). Using an intersectional lens to analyze social systems, it is useful to consider how capitalism, racism, sexism, heterosexism, ageism, and/or ableism intertwine to stratify society and impact life chances for individuals and groups. Collins & Bilge (2020) combine the critical inquiry into inequalities and stratification with critical praxis to advance social justice. Thus, intersectionality is not only a lens and theory but also a potential solution to social problems, reminding sociologists that the many status intersections of race, social class, gender, sexuality, age and/or disability should be considered when seeking remedies to social ills.

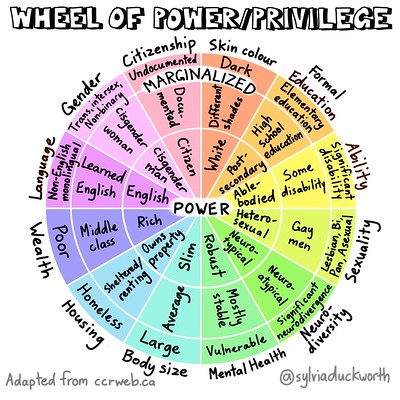

Review the illustration below and consider in which sections you are operating from a place of privilege, and in which you are on the margins. Do you believe some components are more impactful than others? Which ones and why?

Intersectionality

Originally introduced by legal scholar, Kimberle Crenshaw, the term intersectionality was born of an analysis of the intersection of race and gender. Her analysis of legal cases involving discrimination experienced by African American women involved not only racism but also sexism, yet legal statutes and precedents provided no clear analysis of their intersection, but instead treat them as separate social categories. To understand the intersection of these social categories resulting in their ill treatment, both forms of oppression would need to considered jointly. Crenshaw advocates for social scientists to integrate race and gender into their "frames" to better capture the complexity of life experiences, particularly the experiences impacting African American women. Crenshaw used the example of police brutality and the countless African American male victims, with few recognizing the names of African American women brutalized by the police. The #SayHerName campaign was born of an intersectional frame revealing the importance of naming African American female victims of police brutality such as Breonna Taylor, Sandra Byrd, and Rekia Boyd.

Check out this video of Kimberlé Crenshaw explaining the premise of intersectionality:

Black feminist sociologist Patricia Hill Collins (1990) further developed intersection theory, which suggests we cannot separate the effects of race, social class, gender, sexual orientation, age, disability, and other attributes. ‘‘The events and conditions of social and political life and the self can seldom be understood as shaped by one factor . . . . Intersectionality as an analytic tool gives people better access to the complexity of the world and of themselves’’ (Collins, 1992, p.2). We are all shaped by the forces of racism, sexism, classism, heterosexism, ageism, and ableism, though we are likely impacted very differently by these forces.

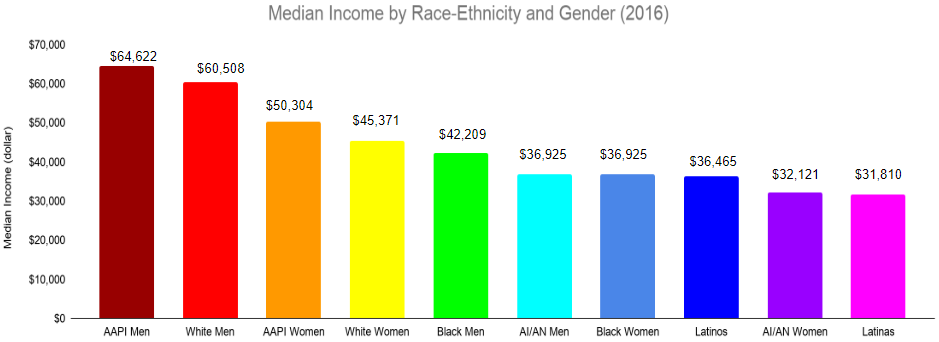

When we examine race and how it can bring us both advantages and disadvantages, it is important to acknowledge that the way we experience race is shaped, for example, by our gender, social class, sexual orientation, age, disability and other statuses which are structured into our social systems. Multiple layers of disadvantage intersect to create the way we experience race, evidenced in concepts such as double jeopardy or triple jeopardy when an individual has two or three potentially oppressive statuses, respectively. For example, if we want to understand prejudice, we must understand that the prejudice focused on a Euro American woman because of her gender is very different from the layered prejudice focused on a poor Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) woman, who is affected by stereotypes related to being poor, being a woman, and her race-ethnic status. In contrast, writer Alice Walker suggested these individuals instead may have double or triple insights into the human condition. Rosenblum and Travis (2011) have argued that what one notices in the world depends in large part on the statuses one occupies . . . thus we are likely to be fairly unaware of the statuses we occupy that privilege us . . . [and] provide advantage and are acutely aware of those . . . that yield negative judgments and unfair treatment.

Collins (1990) writes that not all African American women experience life, and hence life chances, the same. A middle class heterosexual, Christian African American woman has more privileges than a poor, lesbian African American transgender woman. In fact, Collins explains that there are no pure oppressors or pure victims. In the previous example, this more privileged African American woman may be oppressed based on her gender and race-ethnicity, but she may be oppressive based on her religion, social class, and sexuality.