8: Our Way Forward

- Page ID

- 145370

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)At the end of the module, students will be able to:

- evaluate responses and strategies to coping with subordinate or minority status

- explain racial and social justice practices and social movements

- explain the importance of race and ethnicity in the creation of cultural expressions, social developments, progress, and change

- summarize the process for creating cultural awareness and building cultural intelligence

- demonstrate methods and approaches for working with others in a culturally diverse society

- describe and apply anti-racist and anti-colonial practices

KEY TERMS & CONCEPTS

|

Acceptance Adaptive Responses Alternative Movements Anti-Racist & Anti-Colonial Tools Approaches to Reducing Prejudice Assertiveness Assimilation Avoidance Change Agents Change-Oriented Responses Conflict Prevention Strategies Conflict Reduction Techniques Conflict Resolution Conspiracy of Silence Contact Hypothesis Cooperativeness Cross-cultural Conflict Cultural Bias Cultural Intelligence Cultural Realities |

Displaced Aggression Dynamics of Power Education Experiential Exercise Global Consciousness Individual & Group Therapy Interpersonal Conflict Persuasive Communication Race-Based Traumatic Stress Reform Movements Reframing Religious or Redemptive Movements Resistance Movements Resocializaton Revolutionary Movements Social Movement Socio-Cultural Lenses Toxic Stress Truthfulness Types of Ignorance |

INTRODUCTION

The fight for equality and humanitarian treatment in the United States has been difficult and often absent for racial-ethnic groups throughout our history. Today, many Americans remain blind or apathetic in acknowledging and correcting the transgressions of our past. Fulfilling the promises created by the founders of this nation is attainable and may be realized if people act, hold each other accountable, and live by the words pledge and vowed in the Constitution by its citizenry.

RACIAL & SOCIAL JUSTICE

At the beginning of our story, we asked if someone had ever misrepresented or taken advantage of you. We asked these questions to invoke an emotional frame of reference for you to begin to empathize and develop understanding about the impact of the United States and its history on people of color. It is difficult to comprehend another person’s pain, particularly if we have never experienced it ourselves, so we began with generalizations to help you build a mental bridge about the feelings that are invoked when you have been wronged or treated unfairly by others.

Racism and discrimination inflate race-based traumatic stress. Stress is a physiological and cognitive reaction to situations of perceived threats or challenges (Resler, 2019). Day-to-day stress is tolerable with coping skills and supportive relationships; however, exposure to adverse experiences over a long period of time can become harmful and toxic. Individuals experience toxic stress when they must maintain a level of hyper-vigilance to unpredictable or dangerous environments. Being a racial minority leads to greater stress because of the prevalence of systemic racism and racial discrimination (Resler, 2019). Racial minorities are in a constant state of red alert from having to anticipate racial events and interactions and being cognitively aware of how to respond appropriately for survival. Racial trauma can result in psychological affliction, behavioral exhaustion, and physiological distress (Comas-Diaz and Jacobsen, 2001).

When we are confronted by pain or trauma inflicted by others, we either develop adaptive strategies or change-oriented strategies to cope. Depending on the social conditions, our responses to such social and psychological distress vary. Minority groups, as a whole, function the same way by adapting to or changing the status quo.

There are four common adaptive responses to subordinate or minority status: acceptance, displaced aggression, avoidance, and assimilation (Farley, 2010). Each adaptive response consents to having unequal status and attempts to adjust or live within the social system. Acceptance involves the greatest degree of giving into a subordinate position. Some minorities accept inferior status because they are convinced the ideology of the dominant group is superior, others believe they cannot change their situation and become apathetic, and several pretend to accept their status by playing on dominant group prejudices such as acting dumb to fool the majority and navigate social contexts (Farley, 2010).

Displaced aggression is another adaptive response to subordinate status. In social systems where people are powerless, frustration and hopelessness are directed towards each other rather than the dominant group. Because minorities are oppressed by the dominant group and the power structure does not permit a mechanism for them to retaliate or strike back, they displace their emotions and aggression onto each other (Farley, 2010). Examples are seen in communities of color where minority group members commit violent acts on one another. In a state of displaced aggression, it is common for minorities to scapegoat or blame each other for their lack of power and lower status. Fighting each other releases the pain of being powerless while also inflating the misnomer of having more power than their minority group counterparts.

Another common method for adapting to subordinate status is avoidance. Some minority group members avoid contact with the dominant group to cope with the state of being powerless. By avoiding contact with the dominant group, minorities are able to forget or ignore their subordinate status (Farley, 2010). As a way of avoiding their inferior reality, other minority group members attempt to escape by using drugs and alcohol.

Lastly, assimilation is a way minority group members adapt to subordinate status. Assimilation necessitates minority group members to become part of or accepted by the majority or dominant group. This response relies heavily on socially and culturally transforming one’s position or role in society (Farley, 2010). To become part of the majority group or be accepted by the group, minorities must pass or fit into the dominant white culture. In an effort to assimilate, minority group members practice code switching where they alternate between their native or indigenous self into an assimilated and acculturated self.

BIOGRAPHICAL REFLECTION 8.1

THE BLUE MORNINGS

As a child, one of my earliest memories was of the “blue mornings.” That time before the sun rises when the night is almost gone. When I was about six-years-old, I used to wake up afraid because my three other siblings and I were in a strange place, waiting for my mom to come home from wherever she was. I worried about her never coming back.

My childhood had many blue mornings of fear and sadness. My grandmother was from Mexico, and she embodied everything that a Mexican grandmother could be. She died around this time, and suddenly, my 26-year-old mother, who was addicted to heroin, and had four children that she was not used to taking care of, was now motherless, and we were motherless as well as my grandmother had become our mother.

On the next blue morning I remember, my mother was arrested, and we had to go live in a foster home with relatives. I woke up to a year of blue mornings without her because she was in prison for a year. I worried about her and wondered whether she was safe. I was so excited to get mail from her which usually had beautiful drawings.

When she was released from prison, it seemed like we were all going to be together, and we were for about a year. She and my stepfather were both on parole, and we had parole agents visiting our home. That “family chapter” would come to a screeching halt when my stepfather was shot and killed in front of our home later that summer. We moved immediately to stay with my grandfather for a few weeks.

My mother found a boyfriend soon after and left us to move to Los Angeles with him. These blue mornings were packed with fear. We went back to a foster home to live with relatives until she got a place and could come and get us. She eventually did, about two years later, and we lived with her for a few months.

We came home from school one day, while living in Los Angeles, to a packed-up home. My mother announced that we were leaving to go back to Fresno. We were on a Greyhound bus headed back to Fresno to live in a migrant camp for a few weeks, then back to the foster home. These blue mornings were ones of exhaustion. We stayed there for two years until we got to high school.

Throughout the blue mornings of moving, grief, loss, trauma, fear, abandonment, and more loss, God was there. Even if we were the poorest people I knew, even if we moved every school year, even if my mother was lost and was not paying attention to God…he was paying attention to us, we were protected.

The most profound blue morning was a blessing that came at age 21. I committed to a life of faith that included forgiveness and hope for a future. My blue mornings were times that I prayed and spent time with God in the process of building a different life. This helped me develop a life that was not defined by my upbringing, but instead, redefined. I realized the gift of being born in a country where I had resources and the ability to get educated as a woman of color. Refined in the understanding that I was given many tools to help me step up and out of this life. I also recognized that not everyone is given the same. Because of those blessings, I did well in school and ultimately became a parole agent myself. I recently retired from that career after 25 years and am now a professor of Criminal Justice at a local junior college. God did that. There were so many jobs I was not qualified for, so many instances when the answer should have been no, but it was yes.

In the thousands of blue mornings that I spent with Him…He healed me…He helped me…He restored me…He defined me.

He transformed the blue mornings from a time of sadness trauma to a time of gratitude and hope. Now, the blue mornings are a time that I walk and take in the new day with so much hope. They are the times that I pray and cry out in appreciation for what I get to wake up to every day. The blue mornings no longer represent fear, trauma, loss, and rejection, but represent my special time with God. The time that he reminds me, it’s always bluest before daybreak. It is the best time.

This story “The Blue Mornings” by Guadalupe Capozzi is licensed under CC BY NC ND 4.0

Rather than adapt or accept subordinate status, some minority groups focus on change-oriented responses. Change-oriented responses focus on altering majority-minority relations and transforming the role of the minority group in the social structure and system (Farley, 2010). The goal is to increase the political, social, and economic power of the group while preserving its culture. Change-oriented responses are realized and implemented through social movements. A social movement is an organized effort to bring about social change. Social movements can develop on the local, national, or global level (Conerly, Holmes, & Tamang, 2021).

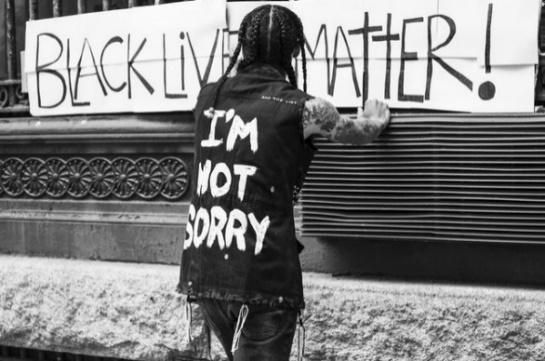

David Aberle (1966) observed and categorized six types of social movements. The first are reform movements which concentrate on modifying a part of social structure or system. Black Lives Matter is a reform movement motivated to stop police brutality by pressuring elected officials and law enforcement agencies to change policing practices. The second are revolutionary movements that center on changing society. The Civil Rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s worked to gain equality rights under the law for Black Americans in the United States. Religious or redemptive movements converge to provoke spiritual growth or change in people. American Indian Residential Schools of the mid-17th through early 21st centuries forced Native American children to give up their culture, language, and religion in an effort to assimilate them into Euro-American ideologies and beliefs. Alternative movements focus on self-improvement both in transforming personal beliefs and behaviors. Anti-Racist practices and support for Critical Race Theory are spreading throughout the United States specifically among White Americans. This alternative movement is grounded in the premise that race is socially constructed and used to oppress and exploit people of color in the United States. Finally, resistance movements strive for preventing change to existing social structures or systems. White supremacy groups involving the American Front, Klu Klux Klan, Proud Boys, and Christian Identity are participating in resistance movements throughout the United States. In California alone, there 72 active white nationalist hate groups supporting resistance (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2020).

Awareness leads people to start a social movement for change or resistance. An effective social movement must have an organized course of action to achieve a goal, a method to create interest or promote the movement, a message to communicate the significance for change or resistance, and a large number of unified and committed people supporting the cause. Social movements develop and evolve in five stages: (1) initial unrest and agitation, (2) mobilization, (3) organization, (4) institutionalization, and (5) organizational decline and possible resurgence (Henslin, 2011). The longevity of a social movement and its effectiveness strongly depend on the ability to maintain involvement of a large group of people over time.

Other social and environmental factors influence the effectiveness of a social movement to create or resist change. The physical environment affects the development of organizations including social movements. People organize their activities and way of life relative to weather conditions. A second factor of success is the political organization or structure of a society (i.e., democratic, authoritarian, etc.). Political authorities have the power to mobilize a community and political agencies can strongly affect the course of development and action in a society. Culture is another stimulating factor of efficacy. Social change requires transformation of social and cultural institutions religion, communication systems, and leadership. If society is not prepared for change, then it will resist so a social movement’s success depends on the cultural climate of the community. Lastly, the mass media serves as a gatekeeper for social change by either spreading information supporting or contradicting a movement’s message (Henslin, 2011). If social movements are unable to reach a large number of people, they cannot form an organized course of action.

REDUCING PREJUDICE

In Module 6, we examined three types of prejudice: cognitive (formulated by beliefs), affective (framed by disdain), and conative (expressed through discrimination). These and other forms of prejudice develop from a multitude of causes including personality, socialization, and historically fixed foundations in our social structure and institutions (Farley, 2010). Because the causes of prejudice are diverse and multi-dimensional, identifying a single solution to reduce societal bigotry is impossible.

The best approaches to reducing prejudice vary by person and context. For some, education and contact with minorities may improve understanding and compassion. Others may need a change in their social setting or environment to escape conformity and the peer pressure of intolerance. Certain people might require therapy to address the underlining personality issues causing narrow-minded thinking and behavior (Smith, 2006).

There are five major approaches to reducing prejudice. Each approach must be geared to a specific individual or situation. The effectiveness of each approach will depend on the techniques practiced and the type and causes of prejudice being addressed.

Stiff and Mongeau (2003) found persuasive communication such as written, oral, audiovisual, and other forms of communication effectively influence people’s attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. If persuasive communication is directly aimed at reducing prejudice, then results reduce prejudicial thinking and behavior. Change occurs when the following conditions are present (Flowerman, 1947; Hovland et al., 1953; McGuire, 1968, Farley, 2010). First, the audience or receiver must be attentive, and the communication or message must be heard. This condition is challenging to overcome because many people have learned to avoid or ignore persuasive communications including advertising, political messages, and propaganda. Second, the audience or receiver must understand or comprehend the communication that prejudice is immoral and harmful. Third, the communication must be received in a positive way or through a positive experience to reinforce discontinuing prejudice as a good idea. Lastly, the audience or receiver must internalize and retain the message to eliminate prejudice. According to Triandis (1971), these conditions are met when those delivering the communication are credible and respected, the content and dissemination of the message are conveyed appropriately at the right time, place, and setting, and the characteristics of the audience are open to the idea of reducing prejudice because prejudice has no psychological or emotional function for them. Therefore, persuasive communication is most effective for people who are unprejudiced or least prejudiced.

Education is an enlightening experience focused on human development. Learning either formally in school or informally enhances growth, development, and understanding by such activities as reading, viewing, and reflection. Education facilitates learning by teaching information including rights, duties, and moral obligations of humanity. Schooling and instruction about intergroup relations helps people breakdown stereotypes and reduces prejudice through simulation and experiential exercises (Lewin, 1948; Fineberg, 1949; Farley, 2010). For example, role-playing activities help students view situations from another person’s perspective, building empathy and understanding about the injustices and inequalities some people confront or face.

Intergroup learning occurs best with impartial teachers, the inclusion of minority role models, non-discriminatory practices, and curriculum free of stereotypical portrayals of minorities (Lessing and Clarke, 1976; Farley, 2010). Dovidio and Gaertner (1999) found educational programs are effective in reducing prejudice when they provide wide-ranging information about minority groups and their members. Some common techniques that address prejudice are teaching facts about race and ethnic relations, imparting tolerance, interactive activities that replicate experiences and evoke real world situations, and intergroup contact.

The contact hypothesis suggests intergroup contact reduces prejudice by exposing people to minority group members. Intergroup contact allows people to discover the inaccuracies or errors in their thinking and understanding about others. Pettigrew (1998) found intergroup contact reduces prejudice by learning about the out-group and in-group, liking people in the out-group, and altering behavior.

Integrated social settings help people see that their stereotypes or fears about out-groups are unfounded (Farley, 2010). Intergroup contact is most effective in reducing prejudice when people involved share similar status and power, and no one can exercise dominance or authority over another. Additionally, contact should be noncompetitive and nonthreatening while inspiring interdependence and cooperation. It is important for contact to go beyond the superficial and work towards effectively changing the attitude regardless of situation or setting (Hewstone, Rubin, and Willis, 2002). When participants engage in intergroup contact, they develop appreciation for each other by listening and learning from each other, engage oneself to speak freely and discuss tough issues or subjects with others, critically self-reflect about power and privilege differences group members experiences, and build alliances to reduce intergroup inequalities (Nagda, 2006).

For some people, prejudice serves as a way to handle personal feelings of insecurity or low self-esteem (Farley, 2010). Individual and group therapy is the best approach to resolve personality problems leading to prejudice. Individual therapy centers on discovering unaddressed psychological issues of prejudice; however, group therapy is the most commonly used to reduce prejudice because it takes less time to create change in more people (Allport, 1954; Smith, 2006; Farley, 2010). Cognitive-behavioral therapy changes personality patterns to reduce prejudice. Rational-emotive therapy helps people develop social relationships by reducing anger and hostility. Researchers have found these forms of therapy include methods that work towards increasing self-acceptance decrease prejudice (Grossarth-Maticek, Eysenck, and Vetter, 1998; Ellis, 1992; Fishbein, 1996; Farley, 2010).

As mentioned previously, experiential exercises including simulation activities are helpful in reducing prejudice. Experiential exercises, like the Privilege and Life Chances activity in Module 7, provide an opportunity for a learner to be exposed to a new condition or a wrong behavior (Armstrong, 1977). To reduce prejudice, these exercises are designed to simulate discrimination to inform people about the irrationality, psychological effects, and emotional consequences of prejudice and discrimination. This approach is often combined with others including education, intergroup contact, and therapy.

Experiential exercises are most effective with thorough discussion, debriefing, and reflection (Fishbein, 1996). Facilitation of the structured exercise centers the learner’s experience and ways to bring about change. This approach is valuable for reducing affective prejudice such as liking or disliking, reducing implicit bias, and encouraging people to take change-oriented action to address intergroup conflict and inequality (Lopez, Gurin, and Nagda, 1998; Farley, 210).

BIOGRAPHICAL REFLECTION 8.2

MY TURN, WHY ENDING RACIAL PREJUDICE IS NOT A HOPELESS CAUSE

I am an African-American man who has never really understood how a person is wired to have prejudicial feelings toward someone simply because of color. I wasn’t brought up that way, and I’ve never bought into the idea that history or tradition is an excuse to behave that way.

Maybe it is because I was raised in a fairly sheltered environment growing up as an African-American child of the 60s; I somehow escaped having the “N” word tossed my way all the way through seventh grade. Maybe I owe it to my private Catholic school education, which kept me effectively cloistered from severe racial slurring incidents.

Don’t get me wrong, I was well aware that I was Black, and I instinctively sensed that there were parts of my hometown that I needed to avoid, on account that I didn’t look like others from those parts. So, I did. And before seventh grade was over, I transferred to a new school where I was very harshly introduced to the ‘N’ word and was reminded of it many times thereafter.

It seems we all cope with racial prejudice in our own way. Some of us deal with it politically, some spiritually, and others rather ignore it as something that hopefully “other people” will have to deal with, but certainly not “me.”

Some people retaliate against racial slurs with violence as it seems the only way to show both the offender and onlookers that the offense is intolerable and will not be tolerated, period. But what if the bigot is bigger and stronger than the subject of the bigotry? Then “whipping his a--” may not be an option to solve the issue. And no, putting a bullet between the offender’s eyes is not the answer either! It just doesn’t seem logical to serve a life sentence behind bars when you were the offended person to begin with.

Since my name is Daryl, not Dwayne Johnson, nor am I interested in shooting anyone, my way of dealing with this issue of race is to write about it, and hopefully you, will see that this racial prejudice business should be just as intolerable for anyone else as for me.

Truthfully, I don’t know if racial prejudice will ever totally be resolved. But I do know that it can be much reduced if the following things occur with increasing frequency:

- Racial slurs of any kind, against any race, or even within the same race should never occur, ever at any time. The idea of Blacks using the “N” word ourselves was apparently meant to diffuse the power of said word, but it was an ineffective strategy. It served only to confirm for many that we have a less than lofty view of ourselves ironically - for using the same word meant to offend us. As a former U.S. Air Force officer, I remember an occasion when I was stationed at a new base. Shortly after my arrival, one of my young black subordinates said to me “Hey, N______, it’s about time you showed up.” That did not occur again of course but looking back I can only roll my eyes in bewilderment and wonder. If Caucasians called each other “Honkeys,” it would seem no less absurd to me.

- We need to minimize telling racial jokes either openly or behind the backs of the race being joked about. This is a big one, and not an easy one for some people to let go of. But when everyone agrees that racial “jokes” are neither funny nor in good taste, we’ll take a big step toward racial harmony. When minorities are defended when no minority is present in the room, then a big step will have been taken toward cultural sensitivity. But as long as the practice of ethnic “jokes” continues, there will always be a secret discontent between races, each one secretly wondering if the other can really be trusted to have mutual respect behind closed doors.

- Schools need to continue taking active steps to promote diversity instruction that teaches accurate history about human trafficking and slavery that occurred over the years, and how that behavior led to where we stand now. There isn’t a single race, not one, that has not made grievous errors historically when it comes to treatment of even its own.

- Finally, we need honest, open discussions where young people feel safe sharing their thoughts regarding aspects of other cultures that they don’t understand, including differing facial features, skin color, language, personal expression, dress and music. But it can’t simply end there. The resultant bridging should be an understanding that different races celebrate and appreciate each other’s differences, not simply their own.

To close, this is not intended to be “Solving Racial Prejudice for Dummies,” nor “The End of Racial Prejudice 101”. And Heaven knows the four areas noted above will not be easy for some of us to do. And I know that some individuals will stubbornly put their foot down and refuse to budge because staying separate from people different from them is more comfortable for them, and it seems to make more sense to them. But in the long run, is it really better, or does it just seem to be?

Racial prejudice won’t end by attrition alone - maintaining a laissez-faire approach to this social problem, in essence waiting until all bigoted people somehow change or die, one by one. If that’s the case, I need to be cryogenically put to sleep for several hundred years. When I wake up, no doubt some of them will still be here waiting for me.

At the end of the day, it’s safe to say that many people of all races are simply weary of racial separatism, and long for a nation where there is a widespread commonality in being just fine with the fact that we are all different. I hope this affirms for many that there is truly hope that one day we will all - or at least most of us, bond together in unity. Our country is worth it.

This story “My Turn” by Daryl Johnson is licensed under CC BY NC ND 4.0

BUILDING COMMUNITY

Racial equity requires change agents or people who are willing to initiate and manage struggles over injustice, inclusion, and unequal relations of power. Building an equitable society involves altering our social arrangements and behaviors (Bruhn and Rebach, 2007). Transforming society away from prejudice and discrimination means constructing a new social structure where all people have equal rights, liberties, and status.

Meaningful social change starts with each of us. Ending racial prejudice and inequality is everyone’s responsibility. Ivey-Colson and Turner (2020) and the UOTeaching Community (2020) offer some anti-racist and anti-colonial tools from the works of Dr. Ibram X. Kendi, Dr. Robin DiAngelo, Dr. Leilani Sabzalian, Dr. Gloria Jean Watkins (Bell Hooks), and other academic experts. These tools require daily practice to counter racial prejudice and discrimination, systemic racism, and oppression of minority racial and ethnic groups. The following tools serve as a model to 1) inform people about lesser-known facts, 2) confront and address past shame, anger, and blame, and 3) develop empathy (Ivey-Colson and Turner, 2020).

| Education | Enact cultural and linguistic dexterity by harvesting knowledge and facts about racial-ethnic minorities |

| Mindful awareness | Be present in the daily practice of being anti-racist, anti-colonial, and anti-oppressive |

| Courage | Show compassion and vulnerability even when it’s uncomfortable |

| Individuality | Acknowledge the quality and character of an individual rather than perpetuate myths and stereotypes |

| Humankind | Recognize and value the diverse range of human experiences that exists in each of our lives and act as all humans are worthy of compassion or benevolence |

| Anti-colonial literacy | Cultivate egalitarian partnerships and sharing with tribal nations to enhance indigenous education and survivance |

| Anti-racist work | Act and express anti-racists ideas |

| Equality | Engage in treating all humans as equals and promote equity |

| Empathy | Share, think, and care about others |

| Allyship | Take risks and share your privilege to support marginalized groups and people of color |

| Love | Spread love and healing over fear and oppression - Mix care, affection, recognition, respect, commitment, and trust as well as honest and open communication |

|

Source: Adapted from Ivey-Colson, K. & Turner, L. (2020). 10 keys to everyday anti-racism. Greater Good Magazine. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/ten_keys_to_everyday_anti_racism and UOTeaching Community. (2020). Anticolonial pedagogy. University of Oregon. https://blogs.uoregon.edu/uoteachingcommunity/about/anti-oppressive-pedagogy-study-circle/anticolonialism-pedagogy/ |

|

Cultural Intelligence

In a racial-ethnic diverse society, it is becoming increasingly important to be able to interact effectively with others. Our ability to communicate and interact with each other plays an integral role in the successful development of our relationships for personal and social prosperity. Building cultural intelligence requires active awareness of self, others, and context (Bucher, 2008). Self-awareness requires an understanding of our personal identity including intrinsic or extrinsic bias we have about others and social categories of people. Cultural background greatly influences perception and understanding, and how we identify ourselves reflects on how we communicate and get along with others. It is easier to adjust and change our interactions if we are able to recognize our own uniqueness, broaden our percepts, and respect others (Bucher, 2008). We must be aware of our identity including any multiple or changing identities we take on in different contexts as well as those we keep hidden or hide to avoid marginalization or recognition.

Active awareness of others requires us to use new socio-cultural lenses. We must learn to recognize and appreciate commonalities in our lives and cultures not just differences. This practice develops understanding of each other’s divergent needs, values, behaviors, interactions, and approach to teamwork (Bucher, 2008). Understanding others involves evaluating assumptions and truths. Our personal socio-cultural lens filters our perceptions of others and conditions us to view the world and others in one way blinding us from what we have to offer or how we complement each other (Bucher, 2008). Active awareness of others broadens one’s perspective to see the world and others through a different lens and understand diverse viewpoints that ultimately helps us interact and work together effectively.

Today’s workplace requires us to have a global consciousness that encompasses awareness, understanding, and skills to work with people of diverse backgrounds and cultures (Bucher, 2008). Working with diverse racial-ethnic groups involves us learning about others to manage complex and uncertain social situations and contexts. What may be socially or culturally appropriate in one setting may not apply in another. This means we must develop an understanding of not only differences and similarities, but those of social and cultural significance as well to identify which interactions fit certain situations or settings.

As we come into contact with racial-ethnic diverse people, one of our greatest challenges will be managing cross-cultural conflict. When people have opposing values, beliefs, norms, or practices, they tend to create a mindset of division or the “us vs. them” perspective. This act of loyalty to one side or another displays tribalism and creates an ethnocentric and scapegoating environment where people judge and blame each other for any issues or problems. Everyone attaches some importance to what one values and believes. As a result, people from different cultures might attach greater or lesser importance to family and work. If people are arguing over the roles and commitment of women and men in the family and workplace, their personal values and beliefs are likely to influence their willingness to compromise or listen to one another. Learning to manage conflict among people from different cultural backgrounds increases our ability to build trust, respect all parties, deal with people’s behaviors, and assess success (Bucher, 2008). How we deal with conflict influences productive or destructive results for others and ourselves.

Self-assessment is key to managing cross-cultural conflicts. Having everyone involved in the conflict assess “self” first and recognize their cultural realities of personal history and experience will help individuals see where they may clash or conflict with others. If someone comes from the perspective of white men should lead, their interactions with others will display women and people of color in low regard or subordinate positions to white men. Recognizing our cultural reality will help us identify how we might be stereotyping and treating others and give us cause to adapt and avoid conflict with those with differing realities.

BIOGRAPHICAL REFLECTION 8.3

RELIGIOUS & CULTURAL CONFLICTS

The cultural pressure from relatives in Fresno made my father return to his shaman practice. He never really fit in the church to begin with. While in Nashville, he attended church services with us children to “make the church like us.” The church donated clothing, sofas, kitchen items, and sometimes food to our family. He probably felt the need to reciprocate by attending church service. In retrospect, I remember him always being very respectful of all the church services. He sat in church quietly, but he would tell us children afterwards not to take church seriously.

Our family’s church attendance subsequently led to my conversion to Christianity at the tender age of 13, fascinated by concepts of the soul and immortality over sexual curiosity. With the Bible as my guiding principles, I devoted my teen years to serving God and intended on becoming a minister. This mission was short lived when I entered my second year in college at UC Berkeley. As I watched my father lay dying in his hospital bed, I discovered the limitations and hypocrisy of the church. I saw the cultural divide of Hmong clan structure and church practice. Relatives came to visit my father with reverence, telling him what he had meant to them. The church just wanted to know if my father would repent before he died. The cross-cultural misunderstandings, religious conflicts, and differences of being Hmong and American were beyond fixing.

Nevertheless, shortly before my father died, he and I were able to reconcile on the purpose of religion in human life. He was a highly consulted shaman; I was a “prodigal son” so to speak, having returned from a “Jesus freak” journey. There were six of us sons, but I knew he wanted all of us to master a Hmong cultural practice rather than ministering for the Christians. He also noticed I had left the church in disappointment, confusion, and sharp spiritual pain. When a spiritual core is absent – whether it’s taken away or one chose to do away with it (as in my case) – life can seem gloomy, meaningless, void, and even suicidal. For me, an identity crisis ensued from this divergence from Christianity – a mental breakdown that sent me into a spiritual whirlwind of what seemed incurable by man or God. I found a little solace reading “Why I Am Not A Christian,” and “A Freeman’s Worship” by Bertrand Russell. My grades suffered, but I may have begun to find myself.

The Hmong community in the Central Valley has had its share of issues in relations with American mainstream. Some of these challenges included educational gaps, income, racism, domestic violence, social justice, and religious and cross-cultural conflicts. While these issues had been worked on and some progress had been made, they remain critical points to our community as we continue to define our culture, identity, and relations with others racial groups.

This story “Religious & Cultural Conflicts” by Silas Cha is licensed under CC BY NC ND 4.0

Some form of cultural bias is evident in everyone (Bucher, 2008). Whether you have preferences based on race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, (dis)ability, region, social class or all social categories, they affect your thoughts and interactions with others. Many people believe women are nurturers and responsible for child rearing, so some do not support men receiving custody of the children when there is a divorce in the family. Bias serves as the foundation for stereotyping and prejudice (Bucher, 2008). Many of the ideas we have about others are ingrained, and we have to unlearn what we know to reduce or manage bias. Removing bias perspectives requires resocialization through an ongoing conscious effort in recognizing our bias then making a diligent effort to learn about others to dispel fiction from fact. Dealing with bias commands personal growth and the biggest obstacles are our fears and complacency to change.

Additionally, power structures and stratification emerge in cross-cultural conflicts. The dynamics of power impact each of us (Bucher, 2008). Our assumptions and interactions with each other are a result of our position and power in a particular context or setting. The social roles and categories we each fall into effect how and when we respond to each other. A Hispanic, female, college professor has the position and authority to speak and control conflict of students in her classroom but may have to show deference and humility when conflict arises at a faculty meeting she attends. The professor’s position in society is contextual and, in some situations, she has the privileges of power, but in others, she may be marginalized or disregarded.

Power affects how others view, relate, and interact with us (Bucher, 2008). Power comes with the ability to change, and when you have power, you are able to invoke change. For example, the White racial majority in the United States holds more economic, political, and social power than other groups in the nation. The dominant group’s power in the United States allows the group to define social and cultural norms as well as condemn or contest opposing views and perspectives. This group has consistently argued the reality of “reverse racism” even though racism is the practice of the dominant race benefitting off the oppression of others. Because the dominant group has felt prejudice and discrimination by others, they want to control the narrative and use their power to create a reality that further benefits their race by calling thoughts and actions against the group as “reverse racism.”

However, when you are powerless, you may not have or be given the opportunity to participate or have a voice. Think about when you are communicating with someone who has more power than you. What do your tone, word choice, and body language project? Now imagine you are the person in a position of power. What privilege does your position give you because of your race, ethnicity, age, gender, or other social category? Power implies authority, respect, significance, and value. Those of us who do not have a social position of power in a time of conflict may feel and receive treatment that reinforces our lack of authority, disrespect, insignificance, and devaluation. Therefore, power reinforces social exclusion of some inflating cross-cultural conflict (Ryle, 2008). We must assess our social and cultural power as well as those of others we interact with to develop an inclusive environment that builds on respect and understanding to deal with conflicts more effectively.

Communication is essential when confronted with cross-cultural conflict (Bucher, 2008). Conflicts escalate from our inability to express our cultural realities or interact appropriately in diverse racial-ethnic settings. In order to relate to each other with empathy and understanding, we must learn to employ use of positive words, phrases, and body language. Rather than engaging in negative words to take sides (e.g., “Tell your side of the problem” or “How did that effect you?”), use positive words that describe an experience or feeling. Use open-ended questions that focus on the situation or concern (e.g., “Could you explain to be sure everyone understands?” or “Explain how this is important and what needs to be different”) in your communications with others (Ryle, 2008). In addition, our body language expresses our emotions and feelings to others. People are able to recognize sadness, fear, and disgust through the expressions and movements we make. It is important to project expressions, postures, and positions that are open and inviting even when we feel different or uncomfortable around others. Remember, words and body language have meaning and set the tone or atmosphere in our interactions with others. The words and physical expressions we choose either inflate or deescalate cross-cultural conflicts.

The act of reframing or rephrasing communications is also helpful in managing conflicts between diverse people. Reframing requires active listening skills and patience to translate negative and value-laden statements into neutral statements that focus on the actual issue or concern. This form of transformative mediation integrates neutral language that focuses on changing the message delivery, syntax or working, meaning, and context or situation to resolve destructive conflict. For example, reframe “That’s a stupid idea” to “I hear you would like to consider all possible options.” Conversely, reframe a direct verbal attack, “She lied! Why do you want to be friends with her?” to “I’m hearing that confidentiality and trust are important to you.” There are four steps to reframing: 1) actively listen to the statement; 2) identify the feelings, message, and interests in communications; 3) remove toxic language; and 4) re-state the issue or concern (Ryle, 2008). These tips for resolving conflict help us hear and identify the underlying interests and cultural realities.

Conflict Resolution Strategies & Practices

Interpersonal conflict involves situations when a person or group blocks expectations, ideas, or goals of another person or group. Conflict develops when people or groups desire different outcomes, opinions, offend one another, or simply do not get along (Black, et al., 2019). People tend to assume conflict is bad and must be eradicated. However, a moderate amount of conflict can be helpful in some cases. For example, conflict can lead people to discover new ideas and new ways of identifying solutions to problems or conditions and is often the very mechanism to inspire innovation and change. It can also facilitate motivation among groups, communities, and organizations to excel and push themselves in order to meet outcomes and objectives (Black et al., 2019). According to Coser (1956), conflict is likely to have stabilizing and unifying functions for a relationship in its pursuit for resolution. People and social systems readjust their structures to eliminate dissatisfaction to re-establish unity.

The appropriate conflict resolution approach depends on the situation and the goals of the people involved. According to Thomas (1977), each faction or party involved in the conflict must decide the extent to which it is interested in satisfying its own concerns categorized as assertiveness and satisfying their opponent’s concerns known as cooperativeness (Black et al., 2019). Assertiveness can range on a continuum from assertive to unassertive, and cooperativeness can range on a continuum from uncooperative to cooperative. Once the people involved in the conflict have determined their level of assertiveness and cooperativeness, a resolution strategy emerges.

In the conflict resolution process, competing individuals or groups determine the extent to which a satisfactory resolution or outcome might be achieved. If someone does not feel satisfied or feels only partially satisfied with a resolution, discontent can lead to future conflict. An unresolved conflict can easily set the stage for a second confrontational episode (Black et al., 2019).

Anti-racist allies can use several techniques to help prevent or reduce conflict. Actions directed at conflict prevention are often easier to implement than those directed at reducing conflict (Black et al., 2019). Common conflict prevention strategies include emphasizing collaborative goals, constructing structured tasks, facilitating intergroup communications, and avoiding win-lose situations. Focusing on collaborative goals and objectives prevents goal conflict (Black et al., 2019). Emphasis on primary goals help clients and community members see the big picture and work together. This approach separates people from the problem by maintaining focus on shared interests (Fisher and Ury, 1981). The overarching goal is to work together to address the structure of the overarching social concern or issue.

| Conflict-Handling Modes | Appropriate Situations |

|---|---|

|

Competing (Assertive-Uncooperative) |

|

|

Collaborating (Assertive-Cooperative) |

|

| Compromising |

|

|

Avoiding (Unassertive-Uncooperative) |

|

|

Accommodating (Unassertive-Cooperative) |

|

| Source: Adapted from Thomas, Kenneth W. 1977. “Toward Multidimensional Values in Teaching: The Example of Conflict Behaviors.” Academy of Management Review 2:487. | |

Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

When collaborative partners clearly define, understand, and accept tasks and activities aimed at shared goals, conflict is less likely to occur (Black et al., 2019). Conflict is most likely to occur when there is uncertainty and ambiguity in the roles and tasks of groups and community members. Dialogue and information sharing among collaborative partners is imperative and eliminates conflict. Understanding others’ thinking is helpful in collaborative problem solving. Through dialogue, people are better able to develop empathy, avoid speculation or misinterpreting intentions, and escape blaming others for situations and problems which leads to defensive behavior and counter attacks (Fisher and Ury, 1981). Sharing information about the state, progress, and setbacks helps eliminate conflict or suspicions about problems or issues when they arise.

As groups and community partners become familiar with each other, trust and teamwork develop. Giving people time to interact and get to know each other helps foster and build effective working relationships (Fisher and Ury, 1981). It is important for collaborative members to think of themselves as partners in a side-by-side effort to be effective in their anti-racist work and accomplish shared goals. Avoiding win-lose situations among collaborative partners also weakens the potential for conflict (Black et al., 2019). Rewards and solutions must focus on shared benefits resulting in win-win scenarios.

Conflict can have a negative impact on teams or collaborative work groups and individuals in achieving their goals and solving social issues. People cannot always avoid or protect themselves or others from conflict when working collaboratively. However, there are actions everyone can take to reduce or solve dysfunctional conflict.

When conflict arises, you may employ two general approaches by either targeting changes in attitudes and/or behaviors. Changes in attitudes result in fundamental changes in how groups get along, whereas changes in behavior reduce open conflict but not internal perceptions maintaining separation between groups (Black et at., 2019). There are several ways to help reduce conflict between groups and individuals that either address attitudinal and/or behavioral changes. The nine conflict reduction techniques in Table 6 operate on a continuum, ranging from approaches that concentrate on changing behaviors at the top of the scale to tactics that focus on changing attitudes on the bottom of the scale.

| Technique | Description | Target of Change |

|---|---|---|

| Physical separation | Separate conflicting groups when collaboration or interaction is not needed for completing tasks and activities | Behavior |

| Use rules | Introduce specific rules, regulations, and procedures that impose particular processes, approaches, and methods for working together | Behavior |

| Limit intergroup interactions | Limit interactions to issues involving common goals | Behavior |

| Use diplomats | Identify individuals who will be responsible for maintaining boundaries between groups or individuals through diplomacy | Behavior |

| Confrontation and negotiation | Bring conflicting parties together to discuss areas of disagreement and identify win-win solutions for all | Attitude and behavior |

| Third-party consultation | Bring in outside practitioners or consultants to speak more directly to the issues from a neutral or outsider vantage point to help facilitate a resolution | Attitude and behavior |

| Rotation of members | Rotate individuals from one group to another to help understand frame of reference, values, and attitudes of others | Attitude and behavior |

| Identify interdependent tasks and common goals | Establish goals that require groups and individuals to work together | Attitude and behavior |

| Use of intergroup training | Long-term, ongoing training aimed at helping groups develop methods for working together | Attitude and behavior |

| Source: Adapted from Black, J. Stewart, David S. Bright, Donald G. Gardner, Eva Hartmann, Jason Lambert, Laura M. Leduc, Joy Leopold, James S. O’Rourke, Jon L. Pierce, Richard M. Steers, Siri Terjesen, and Joseph Weiss. 2019. Organizational Behavior. Houston, TX: OpenStax College. | ||

Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

Truth Telling & Social Discourse

An unequal part of systems of power is the way discourse operates. Social justice advocates and allies become attuned to bias and exclusion for the stand they take towards speaking the truth about White authority and privilege (Burbules, 2018). In the face of truth, the dominant group creates a context that shields any claims of scrutiny upon Whites and reinforces the unquestionable naturalness or normality of their status and power.

Truthfulness involves accuracy aiming at the facts and sincerity to speak about reality with honest motives in the truth we speak (Williams, 2002). There are many aspects to contemplate in truth telling including awareness of context, history, personal experiences, equity, and justice in the United States. The implication and responsibility for Whites in a racist society centers on the framework of truthfulness; however, various degrees of ignorance about racial-ethnic minorities is problematic making the idea of “truth” relative in the eyes of Whites. Burbules (2018) identified five types of ignorance that influence the racial-ethnic empathy of Whites.

| Type | Characteristics |

| Forgivable | Could not expect to know |

| Lethargic | A lack of effort to find out |

| Apathetic | Should have made the effort to find out |

| Willful | Refuse to acknowledge |

| Suppressed or unconscious | Unable or unwilling to fully acknowledge though aware |

| Source: Adapted from Burbules, N. C. (2018). The role of truth in social justice education . . . and elsewhere. Philosophy of Education Society. | |

The conspiracy of silence has long been the tactic used by the White race to outwardly ignore the mistreatment and injustices bestowed on people of color in the United States (Zerubavel, 2006). Silence is practiced by never publicly discussing or mentioning open secrets such as the sexual assaults and exploitations of slaves by masters in the antebellum South. White conspirators become silent witnesses by keeping the uncomfortable truth hidden in plain sight and perpetuating a sociology of denial including the murder, torture, rape, theft, and other inhumane and unlawful treat to people of color by Whites in the United States (Krugman, 2002).

According to Zerubavel (2006), denial arises from a need to avoid discomfort and pain. To avoid psychological distress, people may choose to block disturbing information from consciousness. The psychological feelings of fear and embarrassment also reinforce denial. It is challenging for some people to talk about issues or conditions that frighten or shame them. The conspiracy of silence has allowed Whites to actively avoid and deliberately refrain from noticing and refusing to acknowledge their presence in the oppression of indigenous and people of color in the United States (Zerubavel, 2006).

Both normative pressure and political constraint maintain conspiracies of silence among the dominant group. The power and status of Whites imparts their control on the scope of attention on racial-ethnic group relations through formal censorship to informal distraction tactics using formal agenda-setting procedures and informal codes of silence (Zerubavel, 2006). As the demographic changes in the United States, it threatens the power, privilege, and status of the White race, pain, fear, and embarrassment grow among the dominant group. The White race is now faced with shifts in society and culture, and the need to reconcile White thought, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors with racial-ethnic minority groups is overdue.

SUMMARY

In Module 8, we examined the impact of racism and discrimination on race-based trauma and stress. We learned about the diverse coping mechanisms people of color develop including the adaptive and change-oriented strategies they utilize. You were asked to explore the Native American experience in the United States, and to think about anti-racist and anti-colonial practices to improve your relationships with diverse groups and people. We also explored the five major approaches to reducing prejudice. And lastly, we reviewed the strategies and methods for building community and making connections with diverse populations.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- Discuss the strategies people of color use to cope with their subordinate or minority status.

- Describe anti-racist, anti-colonial practices, ways to reduce prejudice in our society.

- Illustrate ways to resolve and reduce cross-cultural conflict.

- Reflecting on the history and experiences of major underrepresented racial groups including African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinx Americans, and Native Americans, explain the significance of race and ethnicity on the development and progress of the United States.

TO MY FUTURE SELF

From the module, what information and new knowledge did I find interesting or useful? How do I plan to use this information and new knowledge in my personal and professional development and improvement?

REFERENCES

Aberle, D. (1966). The peyote religion among the Navaho. Aldine.

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

Armstrong, J. S. (1977). Designing and using experiential exercises. University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/marketing_papers/26

Black, J. S., Bright, D. S., Gardner, D. G., Hartmann, E., Lambert, J., Leduc, L. M., Leopold, J., O’Rourke, J. S., Pierce, J. L., Steers, R. M., Terjesen, S., & Weiss, J. (2019). Organizational behavior. OpenStax College.

Bruhn, J. G. & Rebach, H. M. (2007). Sociological practice: Intervention and social change. (2nd ed). Springer.

Bucher, R. D. (2008). Building cultural intelligence (CQ): 9 megaskills. Prentice Hall.

Burbules, N. C. (2018). The role of truth in social justice education . . . and elsewhere. Philosophy of Education Society.

Comas-Diaz, L. & Jacobsen, F. (2001). Ethnocultural allodynia. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 10(4), 246-252.

Conerly, T. R., Holmes, K. & Tamang, A. L. (2021). Introduction to sociology 3e. OpenStax College.

Coser, L. A. (1956). The functions of social conflict. Free Press.

Dovidio, J. F. & Gaertner, J. D. (1999). Reducing prejudice: Combatting intergroup biases. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8(4), 101-105.

Ellis, A. (1992). Rational-emotive approaches to peace. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 6(2), 79-104.

Fadiman, A. (1997). The spirit catches you and you fall down : a Hmong child, her American doctors, and the collision of two cultures (1st ed.). Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Farley, J. E. (2010.) Majority-minority relations. (6th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Fineberg, S. A. (1949). Punishment without crime. Doubleday.

Fishbein, H. D. (1996). Peer prejudice and discrimination: Evolutionary, cultural, and developmental dynamics. Westview Press.

Fisher, R. & Ury, W. (1981). Getting to yes negotiating agreement without giving in. Penguin Group.

Flowerman, S. H. (1947). Mass propaganda in the war against bigotry. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 42, 429-439.

Grossarth-Maticek, R., Eysenck, H. J., & Vetter, H. (1998). The causes and cures of prejudice: An empirical study of the frustration-aggression hypothesis. Personality and Individuals Differences, 10, 547-549.

Hamilton-Merritt, J. (1993). Tragic mountains: the Hmong, the Americans, and the secret wars for Laos, 1942-1992. Indiana University Press.

Henslin, J. M. (2011). Essentials of sociology: A down-to-earth approach. (11th ed.). Pearson.

Hewstone, M., Rubin, M., & Willis, H. (2002). Intergroup bias. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 575-604.

Hovland, C. I. Janis, I. L., & Kelley, H. H. (1953). Communication and persuasion. Yale University Press.

Ivey-Colson, K. & Turner, L. (2020). 10 keys to everyday anti-racism. Greater Good Magazine. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/ten_keys_to_everyday_anti_racism

Kennedy, V. (2018). Beyond race: Cultural influences on human social life. West Hills College Lemoore.

Krugman, P. (2000, December). Gotta have faith. New York Times, A35.

Lessing, E. E. & Clarke, C. C. (1976). An attempt to reduce ethnic prejudice and assess its correlates in a junior high school sample. Educational Research Quarterly, 1(2), 3-16.

Lewin, K. (1948). Resolving social conflicts. Harper & Row.

Lopez, G. E., Gurin, P., & Nagda, B. A. (1998). Education and understanding structural causes for group inequalities. Journal of Political Psychology, 19, 305-329.

McGuire, W. J. (1968). Personality and susceptibility to social influence. In E. F. Borgatta & W. W. Lambert (Eds.), Handbook of personality theory and research (pp. 1130-87). Rand McNally.

Nagda, B. A. (2006). Breaking barriers, crossing borders, building bridges: Communication processes in intergroup dialogues. Journal of Social Issues, 62, 553-576.

Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 65-85.

Resler, M. (2019). Systems of trauma: Racial trauma. Family & Children’s Trust Fund of Virginia. https://www.fact.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Racial-Trauma-Issue-Brief.pdf

Ryle, J. L. (2008). All I want is a little peace. Central California Writers Press.

60 Minutes. (2015 August 13). Hmong Our Secret Army. [YouTube]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L4U2P7tsOAQ

Smith, H. (2006). Invisible racism. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 75, 3-19.

Southern Poverty Law Center. (2020). White nationalist. The Southern Poverty Law Center. https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/ideology/white-nationalist

Stiff, J. B. & Mongeau, P. A. (2003). Persuasive communication. (2nd ed). Guilford Press.

Thomas, K. W. (1977). Toward multidimensional values in teaching: The example of conflict behaviors. Academy of Management Review, 2,487.

Triandis, H. C. (1971). Attitude and attitude change. Wiley.

Williams, B. (2002). Truth and truthfulness: An essay in genealogy. Princeton University Press, 246.

Zerubavel, Eviatar. (2006). The elephant in the room: Silence and denial in everyday life. Oxford University Press.