9.2: Nonverbal Communication

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 184661

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- explain the four functions of nonverbal behavior.

- illustrate the six categories of nonverbal behavior.

- differentiate between verbal and nonverbal communication.

- explain the specific nonverbal channels used to communicate.

Although verbal communication, what we say to each other, is most often what we think of when discussing how humans interact, in reality, the vast majority of messages we send are communicated nonverbally. As mentioned earlier, nonverbal communication is upwards of 93% of our communication package. Our use of expressions, gestures, body language, space, and time far outweigh verbal communication in sheer quantity. Furthermore, while we know it is easy to tell a lie, it is far more difficult to show a lie; thus, nonverbal communication is far more believable than verbal.

Nonverbal communication is a significant and powerful venue of communication. It is a large, all encompassing area, and accordingly the definition for nonverbal is quite broad. Nonverbal communication is any nonlinguistic variable stimulating meaning in the receiver. Any communicative component, other than language, stimulating some sort of message in the minds of the receivers is part of nonverbal communication.

Nonverbal behaviors fulfill four important communication functions:

- To Regulate: A function of nonverbal is to control the flow of communication. We need to control the give-and-take of interaction to make sense out of what is being talked about; we need a method for taking turns. Without this, bedlam would result and we would be unable to engage in any sort of organized interchange.

- To Substitute: A function of nonverbal is to take the place of verbal. Often, we cannot use the verbal due to distance, noise, or those around us. Sometimes the nonverbal is simply more powerful and intense than the verbal, so we choose to use nonverbal as a replacement.

- To Illustrate: A function of nonverbal is to accompany and accent the verbal. Verbal communication is rather sterile, and does not always function well to demonstrate the depth or breadth of emotion. Nonverbal communication illustrates the verbal message giving a much deeper, richer sense of what is really meant by what is said.

- To Contradict: A function of nonverbal is to contradict the verbal. At times, we do this quite purposefully. For example, if we are having a rather bad day, and a friend approaches us and says, "How are you?" we will likely respond with something like "I'm fine," which verbally says we are doing okay. However, we will deliver it in a way suggesting the opposite. We do this hoping our friend will ask "What's wrong?" giving us permission to say what we really want to say. Other times, we do not necessarily intend the contradiction.

To fulfill these functions, there are six primary categories of nonverbal behaviors.

- Regulators: Regulators are nonverbal behaviors that control the flow of communication; they fulfill the regulation function. Regulators are actions that aid us in knowing when it is our turn to speak or when another wishes to speak. The most classic regulator would be the way we have been taught to take a turn, to raise our hand. Any nonverbal variable such as a gesture, vocal factor, or look can function as a regulator. Even the layout of an office or room can encourage and/or discourage certain types of communication, serving a regulatory function.

- Emblems: Emblems are nonverbal behaviors that replace the verbal; they fulfill the substituting function. Emblems are used when it is not possible to use the verbal, or when the nonverbal would be more powerful. Not all gestures are emblems. To qualify as an emblem, the meaning of the gesture must be fairly clear and broadly understood among a group of people. For example, the peace sign is an emblem, as is the "finger." The meanings of these emblems are fairly widely understood, within our culture, and function in place of the verbal message.

- Illustrators: Illustrators are nonverbal behaviors that accompany and accent the verbal messages; they fulfill the illustrating function. Illustrators add a richer sense of meaning and intent to the verbal message. We all know that how something is said can be as or more important than the words. Take a phrase such as "I'm angry," and think of how many different ways it can be said, all the way from the mild, calm version indicating very controlled discontent to the shouted, intense, red-faced statement. While the verbal message does not change, the nonverbal message changes dramatically, changing the entire message significantly.

- Affect Displays: Affect displays are nonverbal behaviors communicating the nature of the relationship. Affect displays fulfill different functions. When a friend is having a bad day, we may offer a hug or a hand on the shoulder as an emblem communicating affection for our friend. The softer voice lovers use for each other is an affect display illustrating their affection for one another. A wedding present, graduation present, or other such gifts are nonverbal displays of being connected and caring for the recipients. Most of us can identify friends, couples, and strangers simply based on nonverbal behaviors such as touching, physical distance, eye contact, and other non-linguistic variables.

- Double-Binds: Double-bind messages are when the nonverbal and verbal messages oppose each other; they fulfill the contradictory function. We send one message via the language, the verbal, yet we send an opposing message nonverbally. Sarcasm is a specific type of double-bind message in which the verbal message may sound supportive, yet the nonverbal delivery is contradictory and insulting. In this case, we virtually always believe the nonverbal to be the accurate message. The concept of "double-bind" comes from the dilemma that may arise as to which message to respond to, the verbal or the nonverbal. Often, neither is a good option because the individual is stuck in a double-bind.

- Adaptors: Adaptors are a little different than the others. Adaptors are nonverbal behaviors used to satisfy a personal need, and not intended to communicate with others. These are actions we undertake to deal with personal issues, such as scratching an itchy nose, which we do not intend as a communicative act yet can send messages. Since everything about us communicates, even if we do not intend a gesture or movement to have communication value, the observer will often attach meaning to those actions. In public speaking, we commonly see many adaptors, especially among novice speakers. We see nervous actions such as playing with a notecard, looking around, and fidgeting. The actions are used to satisfy the personal issue of anxiety. The speaker is trying to manage the rush of adrenaline triggered by the anxiety and is not deliberately trying to communicate their nervous state. Nonetheless, the anxiety does get communicated.

Verbal and nonverbal behaviors work together within our communication package in complementary ways, yet each has characteristics not shared with the other.

- Nonverbal communication is more ambiguous; thus, it is more context dependent. Because most nonverbal gestures and actions are less well defined than the words, we get a sense of what those variables mean only within the broader context of other nonverbal clues and the verbal communication. While words can stand alone, we cannot take nonverbal clues in isolation; rather, we must see them as part of the whole package, and we must use all the incoming stimuli to generate a more accurate interpretation.

- Nonverbal is continuous and inevitable. Because of nonverbal communication, "we cannot not communicate." Although we can quit sending verbal messages, we never stop sending nonverbal messages such as appearance, posture, or overall demeanor. Even if we are totally unaware of being observed, we are sending messages. Our absence can even have communication value. If a person is noticeably missing at a meeting or a party, the others may speculate about the absence and what is going on; in other words, not being present also sends messages. The lack of a reply to a text may stimulate all sorts of messages.

- Nonverbal is more multi-channeled. We have five senses, and all of the senses can be used to experience nonverbal clues. Verbal communication primarily relies on hearing (in oral communication) or sight (in reading). Nonverbal communication clues can be smelled, tasted, touched, seen, or heard.

- Nonverbal is more emotionally revealing. Although phrases such as "I'm angry" can give the listener a broad sense of what the speaker means, it is the addition of the nonverbal communication, the vocal characteristics, posture, and eye contact, which really gives us a sense of just how angry the person is. The verbal communication points the listener in the direction of the speaker's thoughts, but the nonverbal "paints the picture," adding the richness and nuances of what they mean.

- Nonverbal is more believable. Realistically, telling a lie verbally is quite easy; however, demonstrating a lie with all our nonverbal traits is far more difficult. Hence, we tend to assume that when we receive a mixed message, the nonverbal communication is the true or accurate message. Nonverbal communication is upwards of 93% of our communication package, so the sheer amount of nonverbal can overwhelm the verbal.

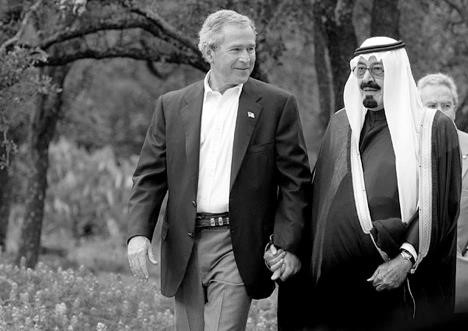

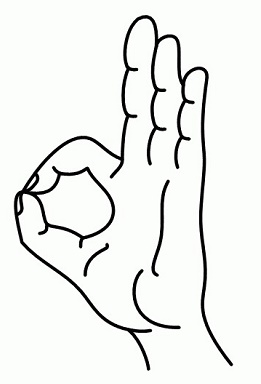

Nonverbal is more culturally specific. Languages can change from culture to culture, but nonverbal communication changes to an even higher degree. How words are said, vocal patterns, gestures, distance, and other factors vary to a much greater degree between cultures. For example, in the Middle East, it is more common for heterosexual males to engage in behaviors we would consider homosexual, such as handholding and kissing. The famous photo of President Bush and Saudi Crown Prince Abdullah holding hands illustrates how important knowledge of these cultural differences can be for successful interaction (Graham, 2007) . In Image 2, the U.S. gesture for "okay" means different things in different countries:

U.S. – “okay”

France – “zero,” or “worthless

Japan – “money”

Germany and Brazil – vulgarit

From Verderber, Interact 14th ed, 2016.

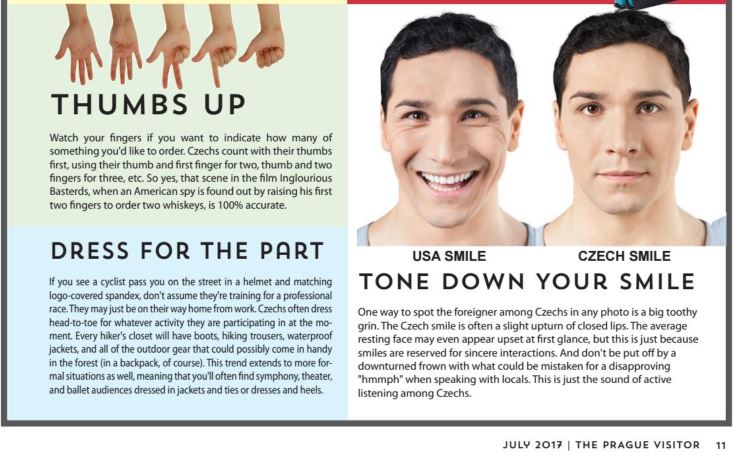

Even something as simple as smiling can vary by culture. In Marina Krakovsky’s (2009) article, “Global Psyche: National Poker Face,” she reports on how smiling is viewed differently in Russia than in the U.S. She states, “Just as Americans mistake Russian reserve for surliness, Russians find friendly American smiles phony" (para. 5). In The Prague Visitor, 2017, July (Image 3), Americans are advised to alter their smiles to better fit into the Czech culture (p. 11).

Perceptions of time also vary by culture. According to Rick Vecchio (2007), in the nation of Peru, the movement, “La Hora sin Demora,” attempted to move from a highly polychronic mindset to a more monochronic mindset. However, such perceptions of time “may be too ingrained to change” (para. 3).

Nonverbal communication is a very broad area, much larger than verbal communication. Given the introductory nature of this course, we will touch on some of the more common and interesting components.

Kinesics

Kinesics refers to body language. Consider how much emphasis we put on appearance in American culture. Body shape, posture, eye contact, and clothing factor heavily into the first impressions we get of others. There are a variety of kinesics:

- Facial expression: Our faces are extremely expressive, and our faces alone account for approximately 55% of our communication package, so clearly, facial expression is a significant message source. Our facial expressions work with a combination of three areas of the face: the forehead; the structures around the eyes; and the structures around the mouth. We change the positioning of these three areas to express a wide range of emotions. While virtually all nonverbal communication is cultural, there are six facial expressions known to be universal: anger, fear, disgust, sadness, happiness, and surprise (Matsumoto & Hwang, 2011).

- Eye contact: In American culture, eye contact during conversation is expected, and a failure to make eye contact in western culture carries negative connotations of being shy, lying, or lacking confidence. We also use eye contact to psychologically diminish distance. By catching a person's eye, even across a room, we have momentarily shrunk the physical space and replaced it with a psychological connection. That is why eye contact in public speaking is so important; it pulls the audience and the speaker together. The eyes and the structures around the eyes are quite emotionally expressive. If a person's eyes seem half-open, we may see them as tired, sad, or depressed. If they are wide open, we may see them as energetic, excited, or confident.

- Hand gestures: Many of us “talk with our hands." It is normal and typical to move our hands as we speak. We employ a range of hand gestures, from the simple flip of a hand to very specific, emblematic gestures. In public speaking, novice speakers often try to avoid hand gestures; however, since gesturing is so usual, such an effort only causes the speaker to look even more uncomfortable and unnatural.

- Body posture: We tend to correlate body posture with degrees of confidence. Generally, we assume people who stand erect with shoulders back are more self-assured than those standing slumped over. The same is true for when seated. Teachers regularly see students laid back in their chairs, and they tend to assume the students, due to that posture, are not as attentive or involved as others.

- Body artifacts: We decorate our bodies. We see National Geographic specials on primitive cultures, and may be fascinated by how they use paint or imbedded objects to decorate themselves. Americans do exactly the same thing, but it is more difficult to see it in ourselves. It is always easier to observe and judge others. Body artifacts are the items we use to decorate our bodies in a variety of ways, depending on the situation. These include:

- clothing

- hair

- jewelry/body piercings/tattoos

- scent

- makeup

Although each of these items may seem insignificant, they can actually consume a remarkable portion of our resources and time. Consider how much a person, male or female, with a full head of hair can spend annually on shampoos, conditioners, haircuts, and hair dye. The investment can be quite significant. Clothing can be very expensive, especially if one wants to wear brand name clothing. Many students get a bit of a shock upon graduation, realizing a new job requires specific types of clothing, and the cost can be rather daunting.

We manipulate and alter the artifacts depending on the situation. We look at the situation, determine how we want to be perceived, and then select/alter artifacts in an attempt to trigger the sort of response we desire. For some, we are much less self-reflexive (aware of what we are doing). Spending the day at home, on a free Saturday, does not demand much attention to artifacts. However, for other situations, like a job interview or big date, we are highly self-reflexive, carefully planning how we present ourselves.

Paralanguage

Verbal communication addresses only the dynamics of language itself. Factors about our voice, pitch, rate, and volume are part of paralanguage. Paralanguage refers to vocal characteristics. There are a variety of vocal factors to consider.

- Pitch: Pitch is how high or low one’s voice is. As we know, males tend to have a lower pitch, and women tend to have a higher pitch. Most of us have few problems with pitch. However, a problem can arise when one’s pitch is out of the norm, such as a male with a high pitch, or a woman with a low pitch. Others may make assumptions about the person based on their pitch.

- Rate: Rate refers to how quickly we speak. The average speaking rate is about 125-150 words per minute (Sprague, 2014) and for most us, we rarely have rate issues. However, if a person speaks much faster, we often assume they are nervous or lacking confidence. On the other end, those who speak very slowly may be seen as mentally slow, boring, or dull.

- Volume: Volume is how loudly we speak. The majority of us do not have volume issues. However, a person who speaks too softly may be seen as uncertain or less confident. A person speaking too loudly may be seen as overbearing and obnoxious. As public speakers, one skill we must learn is how to adapt our volume to the specific physical context, speaking loudly enough for the whole audience to hear without overpowering the front row.

- Quality: The quality of our voice refers to how smooth or harsh we sound. As with most variables, most of the time we do not have any problems. However, someone with a very harsh voice may be difficult to understand, or someone with a very smooth voice may be seen as untrustworthy.

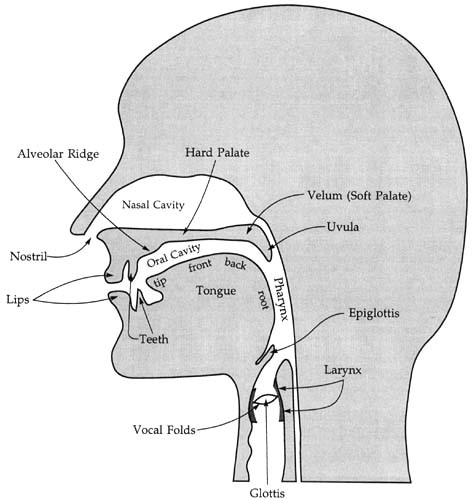

- Articulation: Articulation is our ability to make the sounds of the language. Every language has a phonetic alphabet. The phonetic alphabet is the collection of sounds a person needs to use to speak that language. American English, has about 40 sounds in its phonetic alphabet (there is no relation to the written alphabet) (University of Oregon, 2013). While some of the sounds for English may also be used in other languages, there are differences in the phonetic alphabets as we move from one language to another.

As infants, we are exposed repeatedly to the sounds of our native language; thus, we learn to articulate those sounds quite naturally. As we grow, we also lose the ability to make other sounds like native speakers. When we speak a foreign language, many of us will have noticeable accents; we cannot articulate all the sounds like natives.

Accent coach, Amy Walker, demonstrates how accents are simply differences in articulation.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Video 1 https://youtu.be/3UgpfSp2t6k

To articulate, we use articulators. We force air from our lungs through our larynx, our voice box, where pitch is controlled. As the sound moves into our heads, it resonates (echoes) in our sinuses and upper chest. This is why we sound so flat when sick: our sinuses are plugged, our voice cannot resonate and does not develop the richer sound. As the sound moves through our mouths, we use our lips, tongue, teeth, hard palate, and soft palate to mold and shape the sound. We learn to rapidly and unconsciously readjust our articulators to form the necessary sounds.

- Enunciation: Enunciation refers to how clearly we speak. Articulation is the ability to make the sounds; enunciation is how well we do it. A person who mumbles probably does not have an articulation problem, but they are not choosing to enunciate clearly. For others to understand us, we must enunciate appropriately to send crisp, clear messages.

- Pronunciation: Pronunciation refers to making the correct sounds for the word. We must speak the words correctly or others may infer we are not sure of what we are saying. As a public speaker, correct pronunciation is important to maintain a high level of credibility. Fortunately, with the internet, we can access sources, like Merriam Webster online, where we can read about the word and also hear the correct pronunciation.

In addition to these variables, one that is especially problematic for public speakers is disfluencies. Disfluencies are words or sounds that interrupt the smooth flow of the symbols. These are the classic sounds such as "uh," "um," and "ah." Disfluencies also include identifiable words when they are not used for their meaning. Common ones include "like," "you know," "I mean," "okay," "whatever," and so on. We use these disfluencies because in our culture silence is usually perceived rather negatively. We fill the silence with disfluencies to indicate we are thinking, to maintain control of the conversation, or to give us a moment to think of what to say.

Given these occur quite naturally in our conversation, to eradicate them completely is a questionable approach. A person with no disfluencies whatsoever can seem too "canned" or too "slick." Rather, the goal should be to minimize them as best as possible. Putting too much emphasis on eradicating them can backfire, causing a person to become far too self-conscious of their vocal style, actually leading to an increase in disfluencies. When the situation is important, monitor disfluencies and work to use as few as possible.

Space

We use the space around us to send numerous messages which can significantly impact the type and quality of communication occurring. There are two variables to consider: territoriality and proxemics.

Humans are territorial creatures because we like to feel we have control over our space. Territoriality, refers to our ownership of space. Whether we actually own the space in a legal, financial sense is not as important as a feeling of ownership. Homeowners understandably have a strong sense of ownership of their home and feel very protective toward it. Faculty have a sense of ownership of their office, even though the college or university actually owns it. Our territories can be large such as acres of land, or as small as a side of the bed or a dresser drawer. One common situation students experience involves where they sit in class. Most students will sit in the same place all semester, unless forced to change. Even though they know they can sit elsewhere in the room, they may experience a moment of uncertainty upon entering the class and seeing someone in their chair. The power of territoriality is quite strong.

Just like other animals, we mark our territory. We do, however, employ somewhat cleaner methods of doing so. Central markers are placed in the space to let others know we claim the space as ours. Nathan enters the classroom a few minutes early, places his books on a desk, and then leaves to go to the restroom. His books are a marker claiming that desk as his. The chance of anyone moving Nathan’s marker is pretty low. Boundary markers identify the edges of territory. Fences and hedges serve as boundary markers for one's property. If a number of people are sitting around a table, they will have imaginary boundary markers, dividing the space for everyone’s use. Finally, ear markers label our space. Nameplates on doors or an address on a house serve as ear markers. Teenagers may have a sign on their bedroom door, emphasizing it is their space and should be respected.

The nature of our territory can communicate important messages about ourselves. There are several variables that come into play:

- Size: Generally, we associate larger territory with more power and less territory with less power. Consider what is needed to have a lot of territory: money. In U.S. culture, money and power are virtually synonymous. In corporations, battles may occur over who gets the larger office because we clearly link territory size and power.

- Location: Where the territory is located can be important. Most communities have "rich" parts of town and the "poor" parts, the proverbial "other side of the tracks." Parents may ask where their child’s friends live to use as a clue about what the family may be like. In addition, we generally assume those who work on the upper floors of an office building have more power.

- Control of Access: The more control we have over who can access our territory, and when they can access it, may show we have more power. People who own their own home have more control of access than people who share an apartment with roommates. Executives in large corporations may have two or three assistants who control who gets an appointment or may have an office on a floor accessible only by a special elevator or code.

- Arrangement/Artifacts: Just as we use artifacts to alter our appearance, we also decorate our space with artifacts, such as furniture, wall hangings, carpets, paints, and knickknacks. The types of artifacts we select, and how we arrange the artifacts, sends messages about who lives in the space. This is a multi-billion-dollar industry in the U.S.; every furniture, paint, drapery, and flooring store feeds our need to make spaces our own. We also read into these artifacts. Consider what a person might think of someone simply by looking at their bedroom. What would they think of the person living in that space?

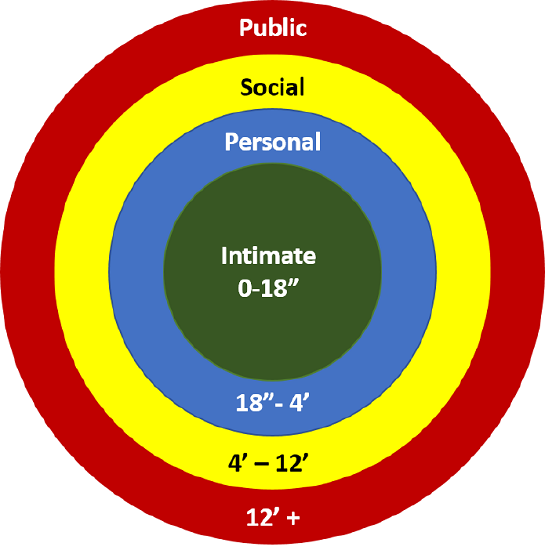

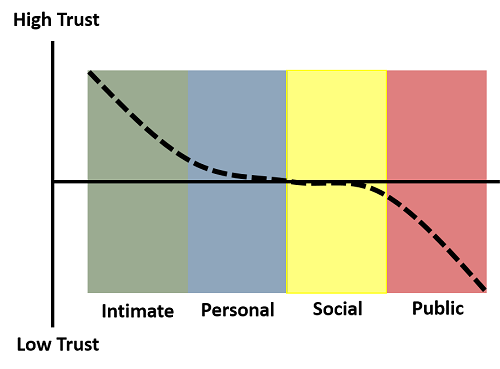

In addition to being territorial and wanting to feel we "own" space, we also use space in another manner, called proxemics. Proxemics refers to the distance between people. We have all experienced someone standing too close to us, making us feel uncomfortable because they "invaded our space." According to Edward Hall (Griffin, 2013), the U.S. American culture has four "zones" with which we work.

1. The intimate zone ranges from touching to about 18". We reserve this level of physical closeness for those with whom we have a strong emotional relationship and for those with whom we have a high level of trust. Except for occasional handshakes and hugs, there are few people we let remain in our intimate zone for very long.

2.The personal zone ranges from about 18" to about 4 feet. This is the zone we use for friends and for those with whom we interact on a regular basis, but with whom we do not have a close, emotional relationship, and for whom touch is not a typical part of the relationship.

3.The social zone ranges from about 4 feet to about 12 feet (although the distances are much more vague at this point). Our "neutral" zone is used for those with whom we have to interact, but with whom we have no established relationship. This is our business or more formal distance.

4.The public zone is 12 feet and larger. We keep this distance between us and anyone who, or anything that, makes us uncomfortable. We want to keep as much distance as we realistically can.

All the zones are related to emotional closeness and trust. As the trust increases, the comfortableness with physical closeness increases. We do not feel as threatened so we allow them to get closer to us.

Although the zones were drawn as round, realistically their shape will change depending on the situation. For example, when sitting next to someone in a movie theater, we still have space in front of us to serve as our safety zone. The sizes of the zones also change according to the space available. At a crowded party or in a full subway car, we may find ourselves touching people we do not know, not because of a comfort level with them, but simply because we have no choice. We do not maintain those precise distances with each individual in those specific types of relationships. For example, we stand closer than four feet when ordering our meal at a fast food restaurant, so this seems to violate the proxemic rules. However, this variation in actual distance changes because we can use substitutes for actual distance. We can hold objects, such as books or a drink, in front of us that act as a replacement for distance. We use tables, desks, chairs, and body orientation as other types of replacements. At the fast food restaurant, there is a large counter between us and the server, replacing the actual distance, giving us a feeling of safe space.

If our space gets violated, which it frequently does, we definitely notice it. It is a powerful type of external noise. It is so powerful, a violation usually shifts the focus from the conversation to the violation, and until the violation is corrected, it is very difficult for us to resume our focus on the conversation. This does not mean we stop talking to move; rather, we usually try to keep talking, but the proxemic violation severely interferes with our focus on the conversation. We will try to move or use a substitute to re-establish a comfortable distance, but until the proxemic violation is rectified, it is foremost in our minds.

Proxemics are highly cultural. While our U.S. “personal” zone is 18”-4’, in the Middle East, it is 8-12”, much smaller than we are accustomed to (Changing Minds, 2013). It is important for people engaging in intercultural exchanges, such as politicians, business people, or even just tourists, to realize those differences to avoid potentially embarrassing or insulting situations.

Chronemics

Chronemics refers to our perception and use of time. Chronemics is not about time itself; rather, it is how we view and interact with time. Perceptions of time vary among individuals and extensively among cultures. Americans are notoriously time-fixated. We see time as a commodity, like money, something to be spent wisely. Other cultures are much more relaxed about time.

Americans see time as monochronic. We see time being a linear progression, and once time has passed, it is gone. We are generally very concerned about scheduling our time carefully, since we time as a resource to be spent wisely. We have seen an explosion of the use of day planners, calendar apps, and other time management tools. Just like using home budgeting programs for money, we use tools to budget our time.

Many other cultures see time differently. They see time as polychronic.In these cultures, time is much more fluid, flexible, and less absolute. Multiple events may be "scheduled" at one time, but the person attends whichever seems most important. Less concern is given to punctuality, and more to addressing whichever events and needs are most important. In monochronic cultures, people have a tendency to let schedule control action, while in a polychronic culture, people control action. They are not driven by a calendar or schedule.

There are three variables of chronemics that illustrate how we see time differently:

- Punctuality is our perception of what it means to be "on time." We all have experienced individuals and situations where differences in punctuality had the potential to cause conflict.

- Duration is our perception of how long something should last. We learn to expect events to be of certain lengths. Movies, meetings, classes, and so on have lengths we have come to expect as normal. When we feel the duration has been exceeded, we get anxious and are ready for the event to be finished.

- Activity is our perception of what occurs at what time of day, and how much should occur in a given time frame. Most of us assume at 3 a.m. we are sleeping. We associate that time with a specific activity. Of course, those associations will vary. For some, 10 p.m. is an appropriate bed time, while others laugh at the idea of going to bed so early. Some feel that getting out of bed at 10 a.m. is horrendously late and irresponsible. Some of us are high activity; we like to see a lot happen. Some are low activity; we like things slower paced. Classes are good examples. Teachers who pack an enormous amount of material, covered quickly, into a short time frame, are high activity. Teachers, who are the opposite, are more low activity, covering very little in a time frame; working their way more deliberately and slowly through material. Another classic example of this difference is vacationing. A high activity person vacationing with a low activity person is often a recipe for conflict. The high activity vacationer will be up early, with a planned and scheduled day, and anxious to do as much as possible. While the low activity person will want to sleep in, do whatever seems interesting at the moment, and just "go with the flow."

If individuals have different chronemic mind-sets, conflict can occur. The assumptions and expectations vary, thus, we have disagreements over what should happen. We make assumptions about others based on their use of time. The low activity teacher may be seen as "boring," and "dull" to some, while others may like the pace. The high activity teacher may be seen by some as "frantic" and "hyper," while others like the faster pace. People who have a strong sense of punctuality may be seen as either "uptight" or "responsible," depending on the other person's point of view.

Haptics

Haptics refers to touch. Touch is the most powerful and basic form of communication. Nothing replaces the power of touch.

The offense of a rude comment pales in comparison to the offense of an inappropriate touch. Touch is such a big issue we have laws defining some touch as illegal; there are few laws regulating personal comments. The irony is, as humans, we need to be touched. We have experienced moments when a hug or a touch said far more than any language. The intimacy a loving couple experiences in sex cannot be replicated by any sort of language.

Where we can touch another person, and when we can touch them, is directly related to the nature of the relationship. Most of us have experienced the growth and development of the physical aspect of an intimate relationship. Through trial and error, experimentation, and even talk, we determine a comfort level of touch for each relationship. The level of touch will change as the relationship changes, but generally we consider the progression of the touch rules to moderately correspond to the progression of the emotional relationship.

As with proxemics, a violation of touch rules shifts the focus to that violation, often to a much more extreme degree than with proxemics. Until the violation is resolved in some fashion, it is difficult, if not impossible, to continue the conversation with any real sense of concentration. For minor violations, simply backing off, increasing distance, and/or apologizing may resolve the issue. For serious violations, relationships may end, law enforcement may be involved, or jobs may be lost.

Key Concepts |

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

Nonverbal Communication

Four Functions of Nonverbal Behaviors

- To regulate

- To substitute

- To illustrate

- To contradict

Six Categories of Nonverbal Behaviors

- Regulators

- Emblems

- Illustrators

- Affect Displays

- Double-Binds

- Adaptors

Differences between Verbal and Nonverbal

- Nonverbal is more ambiguous

- Nonverbal is continuous and inevitable

- Nonverbal is multi-channeled

- Nonverbal is more emotionally revealing

- Nonverbal is more believable

- Nonverbal is more culturally specific

Specific Nonverbal Channels

- Kinesics

- Facial expression

- Eye contact

- Hand gestures

- Body posture

- Body artifacts

- Paralanguage

- Pitch

- Rate

- Volume

- Quality

- Articulation

- Enunciation

- Pronunciation

- Space

- Territoriality

- Size

- Location

- Control of Access

- Arrangement/Artifacts

- Proxemics

- Intimate

- Personal

- Social

- Public

- Chronemics

- Monochronic

- Polychronic

- Punctuality

- Duration

- Activity

- Haptics

- Territoriality

References |

Changing Minds (2013). Proxemic Communication. Changing Minds.org. Retrieved 9/6/2013 from http://changingminds.org/explanation.../proxemics.htm

Graham, J. (2007). Global psyche: A hands-on approach. Psychology Today. Retrieved from http://www.psychologytoday.com/artic...hands-approach

Griffen, E. (2013). "Proxemic theory of Edward Hall." A First Look at Communication Theory. New York, NY: McGraw Hill. Retrieved 9/6/2013 from http://www.afirstlook.com/docs/proxemic.pdf

Jones, E.J. (2009). Westlake Stop Bench [Photograph]. Retrieved 7/5/2017 from https://www.flickr.com/photos/elijui...-6zsU1JG3LCiH- 9CcHWx-nh87Uv-9tK1gk-dt3uzB-92EKR5-79H281-bo145F-d1K1vE-HpoQfY-Pz32Yy- e8yymB-fnugw-oC7uat- aTnANR-9nVyx3-diRLiq-Khf2c-8UQjUb-o2Vhwc-shrTqh-e4FUu8-7Xsh2E-aDr7rL-r1GJpg- fR3b7A-85RnLP-71cyhh-nHBVcu-rC8THu-tNvZ64-ToDZqE-p82nbh-TbTBYz-VBJ6Cg- UBawBm-ckvEZQ-boiqnH-bo21iM-boPGxH-SrKzMp-bnwUaH-9qbqFD-qnHakS-S79trT- U2LWwQ-9qm1cc-pFA8Ys-SacvYG

Krakovsky, M. (2009). Global psyche: National poker face. Psychology Today. Retrieved from www.psychologytoday.com/print/20211.

Matsumoto, D., & Hwang, H.S. (2011). Reading facial expressions of emotion. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from www.apa.org/science/about/psa...pressions.aspx

Robinson, T. (2010). Google calendar [Photograph]. Retrieved 7/5/2017 from www.flickr.com/photos/starga...-yAWQd-4wNpAp- 5NVk6J-7xhje-iLRQfU-5RzApz-8U4eLG-7enwc-8U1aoR-4ikLU-7uzWio-8ptQeU-94PxfL- 5SYLq3-94jK2e-8WwN2q-5RL7UJ-eRogS-rXQJ3-aKR6N-8WwN7j-7FTiDe-ooBwT- 4hAA66-wwN3Z-8U4exu-dy6Es5-x97EQ-5uw7Rk-4hAzWe-4hEDYd-4hEDRm-96fg9t-HJbRf -4ikLS-7AfyJu-5Ut4eU-wwMXu-92iCQV-3TGGXK-ddy4us-8YvoyY-kvCVA-pSuPX-3JF3Bk- 4hEEFo-33BNJy-oyF1G-4jZJgh-b37Sqe

Sprague, J., Stuart, D., & Bodary, D. (2014). The speaker’s compact handbook (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

University of Oregon Center on Teaching and Learning (2013). Phonemic awareness. Retrieved 9/6/2013 from http://reading.uoregon.edu/big_ideas/pa/pa_what.php

Vecchio, R. (2007). Global psyche: On their own time. Psychology Today. Retrieved from www.psychologytoday.com/print/23962

Walker, A. (2008, January 16). 21 Accents. Retrieved January 09, 2018, from https://www.youtube.com/embed/3UgpfSp2t6k