12: The Issues of Gender and Sexuality Part Two

- Page ID

- 248164

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Gender Stratification and Inequality

Stratification refers to a system in which groups of people experience unequal access to basic, yet highly valuable, social resources. There is a long history of gender stratification in the United States. When looking to the past, it would appear that society has made great strides in terms of abolishing some of the most blatant forms of gender inequality (see timeline below) but underlying effects of male dominance still permeate society (as the last line shows).

Before 1809—Women could not execute a will

Before 1840—Women were not allowed to own or control property

Before 1920—Women were not permitted to vote

Before 1963—Employers could legally pay a woman less than a man for the same work

Before 1973—Women did not have the right to a safe and legal abortion

Before 1981—No woman had served on the U.S. Supreme Court

Before 2009—No African American woman had been CEO of a U.S. Fortune 500 corporation

Before 2016—No Latina had served as a U.S. Senator

Before 2017—No openly transgender person had been elected in a state legislature

After 2022—Women did not have a right to a safe and legal abortion

Household Inequality

Gender inequality occurs within families and households. Here we’ll briefly discuss one significant dimension of gender-based household inequality: housework. Someone has to do housework, and that someone is usually a woman. It takes many hours a week to clean the bathrooms, cook, shop in the grocery store, vacuum, and do everything else that needs to be done. The research evidence indicates that women married to or living with men spend two to three times as many hours per week on housework as men spend (Gupta & Ash, 2008). This disparity holds true even when women work outside the home, leading sociologist Arlie Hochschild (Hochschild, 1989) to observe that women engage in a “second shift” of unpaid work when they come home from their paying job.

The good news is that gender differences in housework time are smaller than a generation ago. The bad news is that a large gender difference remains. As one study summarized the evidence on this issue, “Women invest significantly more hours in household labor than do men despite the narrowing of gender differences in recent years” (Bianchi, Milkie, Sayer, & Robinson, 2000, p. 196). In the realm of household work, then, gender inequality persists.

Health Care Inequality

In January of 2012, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, Kathleen Sebelius, announced that all health care plans were required to provide coverage for contraceptives approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The effective meaning of Secretary Sebelius’ announcement was that contraceptives are considered by the Obama administration to be a requisite component of health care.

The premise of the contraceptive mandate demonstrates present inequities in the American health care industry for male and female patients. Whereas services for male reproductive health, such as Viagra, are considered to be a standard part of health care, women’s reproductive health services are called into question. In the context of the 2012 contraceptive mandate debate, health care professionals ‘ assessments that contraception is an integral component for women’s health care, regardless of sexual activity, went largely unaddressed. Instead, insurance coverage of contraception was framed as a government subsidy for sexual activity. This framing revealed inherent social inequalities for women in the domain of sexual health.

Furthermore, a 2020 Supreme Court ruling stated that employers with a sincere religious or moral objection also can choose not to cover birth control. Also, private plans may or may not cover the option for birth control that best fits the person who needs it, resulting again in additional costs to that person.

Women also experience other difficulties in health care due to biased views of gender. According to a 2018 study, men with chronic pain are viewed by doctors as “brave” or “stoic,” while view women with chronic pain are viewed as “emotional” or “hysterical.” Health care professionals are more apt to dismiss or diminish women’s description of their symptoms such as pain. This can lead to delayed or incorrect diagnoses, continued suffering, and health damage. It can also lead to inadequate management of symptoms. Distrust of health professionals due to negative experiences with them can also lead to the avoidance of medical care.

The Pay Gap

Despite making up nearly half (49.8 percent) of payroll employment, men vastly outnumber women in authoritative, powerful, and, therefore, high-earning jobs (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). Even when a woman’s employment status is equal to a man’s, she will generally make only 81 cents for every dollar made by her male counterpart (Payscale 2020). Women in the paid labor force also still do the majority of the unpaid work at home. On an average day, 84 percent of women (compared to 67 percent of men) spend time doing household management activities (U.S. Census Bureau 2011). This double duty keeps working women in a subordinate role in the family structure (Hochschild and Machung 1989). For additional, optional information, you can learn more at AAUW https://www.aauw.org/resources/research/simple-truth/ .

One reason for these differences, and for women’s lower earnings in general, is their caregiving responsibilities (Chang, 2010). Women are more likely than men to have the major, and perhaps the sole, responsibility for taking care of children and aging parents or other adults who need care. This responsibility limits their work hours and often prompts them to drop out of the labor force. If women rejoin the labor force after their children start school, or join for the first time, they are already several years behind men who began working at an earlier age. Economics writer David Leonhardt (2010, p. B1) explains this dynamic: “Many more women take time off from work. Many more women work part time at some point in their careers. Many more women can’t get to work early or stay late. And our economy exacts a terribly steep price for any time away from work—in both pay and promotions. People often cannot just pick up where they have left off. Entire career paths are closed off. The hit to earnings is permanent.”

Research interviewing women shows that women in leadership positions experience ageism at every age in the workplace. Older women are routinely discounted as outdated and not worthy of advancement, while younger women’s credibility is questioned (Diehl, Dzubinski, and Stephenson 2023).

Another reason is sex segregation in the workplace, which accounts for up to 45 percent of the gender gap (Kelley, 2011; Reskin & Padavic, 2002). Although women have increased their labor force participation, the workplace remains segregated by gender. Almost half of all women work in a few low-paying clerical and service (e.g., waitressing) jobs, while men work in a much greater variety of jobs, including high-paying ones. Part of the reason for this segregation is that socialization affects what jobs young men and women choose to pursue, and part of the reason is that women and men do not want to encounter difficulties they may experience if they took a job traditionally assigned to the other sex. A third reason is that sex-segregated jobs discriminate against applicants who are not the “right” sex for that job. Employers may either consciously refuse to hire someone who is the “wrong” sex for the job or have job requirements (e.g., height requirements) and workplace rules (e.g., working at night) that unintentionally make it more difficult for women to qualify for certain jobs. Although such practices and requirements are now illegal, they still continue. The sex segregation they help create contributes to the continuing gender gap between female and male workers. Occupations dominated by women tend to have lower wages and salaries. Because women are concentrated in low-paying jobs, their earnings are much lower than men’s (Reskin & Padavic, 2002).

This fact raises an important question: Why do women’s jobs pay less than men’s jobs? Is it because their jobs are not important and require few skills? The evidence indicates otherwise: Women’s work is devalued precisely because it is women’s work, and women’s jobs thus pay less than men’s jobs because they are women’s jobs (Magnusson, 2009).

Studies of comparable worth support this argument (Levanon, England, & Allison, 2009). Researchers rate various jobs in terms of their requirements and attributes that logically should affect the salaries they offer: the importance of the job, the degree of skill it requires, the level of responsibility it requires, the degree to which the employee must exercise independent judgment, and so forth. They then use these dimensions to determine what salary a job should offer. Some jobs might be better on some dimensions and worse on others but still end up with the same predicted salary if everything evens out.

When researchers make their calculations, they find that certain women’s jobs pay less than men’s even though their comparable worth is equal to or even higher than the men’s jobs. For example, a social worker may earn less money than a probation officer, even though calculations based on comparable worth would predict that a social worker should earn at least as much. The comparable worth research demonstrates that women’s jobs pay less than men’s jobs of comparable worth and that the average working family would earn several thousand dollars more annually if pay scales were reevaluated based on comparable worth and women were paid more for their work.

Even when women and men work in the same jobs, women often earn less than men, and men are more likely than women to hold leadership positions in these occupations. Government data provide ready evidence of the lower incomes women receive even in the same occupations. For example, among full-time employees, female marketing and sales managers earn only 66 percent of what their male counterparts earn; female human resource managers earn only 80 percent of what their male counterparts earn; female claims adjusters earn only 77 percent; female accountants earn only 75 percent; female elementary and middle school teachers earn only 91 percent; and even female secretaries and clerical workers earn only 91 percent (US Department of Labor, 2011).

Feminization of Poverty

Women disproportionately make up the majority of individuals who live in poverty across the world. The gender wage gap, the higher proportion of single mothers compared to single fathers, and the high cost of childcare create a gendered experience when it comes to living in poverty. Considering the economic situation produced by these factors, women (11 percent) are more likely to live in poverty than men (8 percent) (Fins 2020). Women in all racial and ethnic groups are more likely than White men to live in poverty. United States census data shows that poverty rates are higher for Black women (18 percent), Native American women (18 percent), Latinx women (15 percent), and Asian women (8 percent) (Fins 2020).

The Glass Ceiling

The idea that women are unable to reach the executive suite is known as the glass ceiling. It is an invisible barrier that women encounter when trying to win jobs in the highest level of business. At the beginning of 2021, for example, a record 41 of the world’s largest 500 companies were run by women. While a vast improvement over the number twenty years earlier – where only two of the companies were run by women – these 41 chief executives still only represent eight percent of those large companies (Newcomb 2020).

Why do women have a more difficult time reaching the top of a company? One idea is that there is still a stereotype in the United States that women aren’t aggressive enough to handle the boardroom or that they tend to seek jobs and work with other women (Reiners 2019). Other issues stem from the gender biases based on gender roles and motherhood discussed above.

Another idea is that women lack mentors, executives who take an interest and get them into the right meetings and introduce them to the right people to succeed (Murrell & Blake-Beard 2017).

Part of the problem keeping women out of the highest paying, most prestigious positions is that they have historically not held these positions. As a result, recruiters for high- status jobs are predominantly white males, and tend to hire similar people in their networks. Their networks are made up of mostly white males from the same socio-economic status, which helps perpetuate their over-representation in the best jobs.

Men, on the other hand, can often ride a “glass escalator” to the top, even in female occupations. An example is seen in elementary school teaching, where principals typically rise from the ranks of teachers. Although men constitute only about 16 percent of all public elementary school teachers, they account for about 41 percent of all elementary school principals (Aud et al., 2011).

Sexual Dynamics

Social stigmas surround women’s sexuality in ways that are highly restrictive and contradictory. After sexual encounters, men are praised for their actions and for “scoring.” In contrast, women are often criticized and labeled negatively by peers and society regardless of how they handle sexual advances. If they turn down advances, they are called a “prude” or “bitch,” but if they accept advances, they are labeled as “easy” or a “slut.” Recent research on hookup culture shows that women are being criticized less than they were previously, but the stigma and social responses are still frequently negative, regardless of a hookup attempt’s outcome (Armstrong et al. 2014).

Women’s and men’s experiences with online dating demonstrate differences when it comes to sexual harassment and fear of assault when arranging face to face meetings. Women are more often the recipients of sexually explicit photos and unwanted contact (see below). Men receive unwanted sexually explicit photos or conversations, but the social norms are gendered and reflect a power dynamic in which unwanted contact with women may lead to fear and concerns for safety. Women are twice as likely to say that they are concerned about their physical and emotional risks in dating (Pew Research Center 2020).

Data from PEW research center shows that younger women who use dating sites or apps are likely to report negative interactions with others on platforms. Women were more likely than others to be contacted after they said they were not interested, sent sexually explicit messages or images they didn't request, called offensive names and threatened to be physically harm. Numbers were highest for women in 18-34 age range.

Dating apps have expanded to reach a broader audience. There are apps for queer women, gay men, trans people, Black people, religiously affiliated, kink, etcetera. Apps like Bumble have been developed to put the “power” in the hands of women as they control who can and can’t message them. Her, Lex, and Grindr are specifically made for lesbian, gay, trans, nonbinary, and queer people and attempt to create a safe and accepting space that may not be accessible in other apps like Tinder, Bumble, Match, and Hinge.

Sexual Harassment in the Workplace

Another workplace problem (including schools) is sexual harassment, which, as defined by federal guidelines and legal rulings and statutes, consists of unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, or physical conduct of a sexual nature that is used as a condition of employment or promotion or that interferes with an individual’s job performance and creates an intimidating or hostile environment.

Although men can be, and are, sexually harassed, women are more often the targets of sexual harassment. This gender difference exists for at least two reasons, one cultural and one structural. The cultural reason centers on the depiction of women and the socialization of men. As our discussion of the mass media and gender socialization indicated, women are still depicted in our culture as sexual objects that exist for men’s pleasure. At the same time, our culture socializes men to be sexually assertive. These two cultural beliefs combine to make men believe that they have the right to make verbal and physical advances to women in the workplace. When these advances fall into the guidelines listed here, they become sexual harassment

.

The second reason that most targets of sexual harassment are women is more structural. Reflecting the gendered nature of the workplace and of the educational system, typically the men doing the harassment are in a position of power over the women they harass. A male boss harasses a female employee, or a male professor harasses a female student or employee. These men realize that subordinate women may find it difficult to resist their advances for fear of reprisals: A female employee may be fired or not promoted, and a female student may receive a bad grade.

How common is sexual harassment? This is difficult to determine, as the men who do the sexual harassment are not about to shout it from the rooftops, and the women who suffer it often keep quiet because of the repercussions just listed. But anonymous surveys of women employees in corporate and other settings commonly find that 40–65 percent of the respondents report being sexually harassed (Rospenda, Richman, & Shannon, 2009) In studies of college students, almost one-third of women undergraduates and about 40 percent of women graduate students report being sexually harassed by a faculty member (Clodfelter, Turner, Hartman, & Kuhns, 2010).

Despite the fact that sexual harassment is illegal, most women (and men) who are sexually harassed do not bring court action. Two reasons explain their decision not to sue: they fear being fired and/or they worry they will not be believed. But another reason has to do with the mental and emotional consequences of being sexually harassed. These consequences include relationship problems, a loss of self-esteem, fatigue, depression, anxiety, sleeplessness, and a feeling of powerlessness. These effects are similar to those for posttraumatic stress disorder and are considered symptoms of what has been termed sexual harassment trauma syndrome. This syndrome, and perhaps especially the feeling of powerlessness, are thought to help explain why sexual harassment victims hardly ever bring court action and otherwise often keep quiet. According to law professor Theresa Beiner, the legal system should become more aware of these psychological consequences as it deals with the important question in sexual harassment cases of whether harassment actually occurred. If a woman keeps quiet about the harassment, it is too easy for judges and juries to believe, as happens in rape cases, that the woman originally did not mind the behavior that she now says is harassment.

Houle et al. analyzed data from a study of 1,010 ninth-graders in St. Paul, Minnesota, that followed them from 1988 to 2004, when they were 30 or 31 years old. The study included measures of the respondents’ experience of sexual harassment at several periods over the study’s sixteen-year time span (ages 14–18, 19–26, 29–30, and 30–31), their level of psychological depression, and their sociodemographic background. Focusing on depression at ages 30 or 31, the authors found that sexual harassment at ages 14–18 did not affect the chances of depression at ages 30–31, but that sexual harassment during any of the other three age periods did increase the chances of depression at ages 30–31. These results held true for both women and men who had been harassed. The authors concluded that the “effects of harassment are indeed lasting, as harassment experiences early in the career were associated with heightened depressive symptoms nearly 10 years later.”

In finding long-term effects of sexual harassment on women and men in a variety of occupations and organizational settings, Houle et al.’s study made an important contribution to our understanding of the psychological consequences of sexual harassment. Its findings underscore the need for workplaces and campuses to do everything possible to eliminate this illegal and harmful behavior and perhaps will prove useful in sexual harassment lawsuits.

Women of Color: A Triple Burden

Women of color face difficulties for three reasons: their gender, their race, and, often, their social class, which is frequently near the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder. They thus face a triple burden that manifests itself in many ways. This is an example of the concept of intersectionality, first highlighted by sociologist Kimberlé Crenshaw. This is the idea that various categories, including gender, race, class and ethnicity, interact and contribute towards systematic social inequality. Various forms of oppression, such as racism or sexism, do not act independently of one another; instead these forms of oppression are interrelated, forming a system of oppression that reflects the “intersection” of multiple forms of discrimination. In light of this theory, the oppression and marginalization of women is shaped not only by gender, but by other factors such as race and class.

For example, women of color experience extra income inequality. Earlier we discussed the gender gap in earnings, with women earning 82.2 percent of what men earn, but women of color face both a gender gap and a racial/ethnic gap. Table 4.3 depicts this double gap for full-time workers. We see a racial/ethnic gap among both women and men, as African Americans and Latinos of either gender earn less than whites. We also see a gender gap between men and women, as women earn less than men within any race/ethnicity. These two gaps combine to produce an especially high gap between African American and Latina women and white men: African American women earn only about 70 percent of what white men earn, and Latina women earn only about 60 percent of what white men earn.

These differences in income mean that African American and Latina women are poorer than white women. We noted earlier that almost 32 percent of all female-headed families are poor. This figure masks race/ethnic differences among such families: 24.8 percent of families headed by non-Latina white women are poor, compared to 41.0 percent of families headed by African American women and also 44.5 percent of families headed by Latina women (DeNavas-Walt et al., 2011). While white women are poorer than white men, African American and Latina women are clearly poorer than white women.

Gender-Based Violence

Rape is a type of sexual assault in which one or more individuals forces sexual contact on another individual without consent. Rape is often thought of as a crime committed by a man against a woman, but increasingly, social and legal definitions of rape recognize that this does not have to be the case. In 2012, the Federal Bureau of Investigation updated its definition of rape, which had originally been instituted in 1972, and which previously limited rape to a crime against women. This definition, considered outdated and overly narrow, was replaced by a new definition, which recognizes that rape can be perpetrated by a person of any gender against a victim of any gender. The new definition also broadens the instances in which a victim is unable to give consent. These instances now include temporary or permanent mental or physical incapacity, and incapacity caused by the use of drugs or alcohol.

Rape, then is not always against women. But this obscures another fact: Women are far more likely than men to be raped and sexually assaulted. They are also much more likely to be portrayed as victims of pornographic violence on the Internet and in videos, magazines, and other outlets. Also, women are more likely than men to be victims of domestic violence, or violence between spouses and others with intimate relationships.

The gendered nature of these acts against women distinguishes them from the violence men suffer. Rape, sexual assault, domestic violence, and pornographic violence are directed against women precisely because they are women. These acts are thus an extreme manifestation of the gender inequality women face in other areas of life.

The definition of rape rests on the notion of consent. In modern legal understanding, consent may be explicit or implied by context, but the absence of objection never itself constitutes consent, and consent can be withdrawn at any time. Consent cannot be forced and it cannot be given by certain categories of people considered incapable of consent (e.g., minors and the cognitively disabled).

Sexually violent acts are acts of power, not of sex. This can be seen most clearly when considering war rape and prison rape. War rape is the type of sexual pillaging that occurs in the aftermath of a war, typically characterized by the male soldiers of the victorious military raping the women of the towns they have just taken over. Prison rape is the type of rape that is common (and seriously under reported) in prisons all over the world, including the United States, in which inmates will force sex upon one another as a demonstration of power.

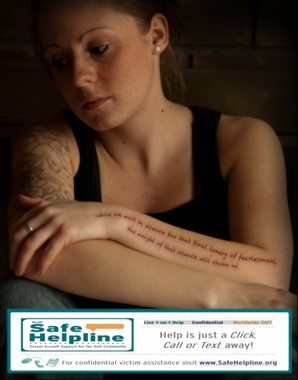

Sexual violence is not mainly about sex; it’s more about control and dominance. In situations of sexual assault, sex is used as a weapon to gain power over another person. The images in the picture below show how violence is excused and victims are unfairly blamed. These victims can be anyone.

Effects of Gender-Based Violence

Rape can cause devastating physical and psychological trauma. In the aftermath of an attack, many victims develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a severe anxiety disorder. Rape victims may also confront a number of emotions related to shame. Often, victims blame themselves for rape. Some victims come to believe they somehow deserved the assault, while others become preoccupied thinking about how the rape could have been avoided.

Although self-blame might seem like an unusual, intensely individual response to rape, it is rooted in social conceptions of rape and victimhood. In the case of rape, victim blaming generally refers to the belief that certain behaviors on the part of the victim, like flirting or wearing provocative clothing, encourage assault. Legal systems may perpetuate victim blaming. For example, in the United States, defendants are guaranteed an opportunity to explain their actions and motivations, which may allow them to instigate conversations about their victims’ sexual past or physical presentation. Lawyers and activists are aware of the negative consequences of this type of conversation in courtrooms, and many have encouraged state legislators to enact rape shield laws, which would prohibit testimony about a victim’s sexual behavior. Nevertheless, victims are often reluctant to report rape because of these social pressures.

There are challenges people face in reporting and dealing with the trauma after such events. Victims often face criticism, rejection, disbelief, and blame and are made to feel like the events they experienced either were not real or were their fault. Others may say or imply that the victim should have been stronger, said no more forcefully, or behaved or dressed differently. Our responses to acts of violence send messages about what types of behaviors and language are acceptable.

The Extent and Context of Rape and Sexual Assault

Rates of sexual violence in the LGBTQIA+ community are the same or higher than in heterosexuals (Human Rights Campaign 2024). Sexual violence will be experienced by about half of all trans individuals and bisexual women during their lifetimes (Flanders, Anderson, and Tarasoff 2020). Their experiences relate to having higher risk factors such as poverty, stigma, and marginalization. Another factor is hate-motivated violence, which can often take the form of sexual assault and sexual violence. There are also high rates of intimate partner violence and sexual assault by partners within the LGBTQIA+ community (Human Rights Campaign 2024).

Transphobia and homophobia are evident in the rates of sexual assault experienced by transgender individuals, with almost half experiencing such assaults in their lifetime. People who are trans and BIPOC experiencing even higher rates (Griffiths and Armstrong 2023). Another concerning trend is that people identifying with the LGBTQIA+ community are less likely to access services, and if they do attempt to get help, they may be denied services due to their sexual or gender identity (Kumar and Joseph 2021). This lack of access further adds to the barriers faced by LGBTQIA+ individuals. The next section of this chapter will examine a few of the other ways that policies and social institutions create barriers for LGBTQIA+ individuals.

Our knowledge about the extent and context of rape and reasons for it comes from three sources: the FBI Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) and the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), and surveys of and interviews with women and men conducted by academic researchers. From these sources we have a fairly good if not perfect idea of how much rape occurs, the context in which it occurs, and the reasons for it.

According to the UCR, which are compiled by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from police reports, 88,767 reported rapes (including attempts, and defined as forced sexual intercourse) occurred in the United States in 2010 (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2011). Because women often do not tell police they were raped, the NCVS, which involves survey interviews of thousands of people nationwide, probably yields a better estimate of rape; the NCVS also measures sexual assaults in addition to rape, while the UCR measures only rape. According to the NCVS, 188,380 rapes and sexual assaults occurred in 2010 (Truman, 2011). Other research indicates that up to one-third of US women will experience a rape or sexual assault, including attempts, at least once in their lives (Barkan, 2012). A study of a random sample of 420 Toronto women involving intensive interviews yielded an even higher figure: Two-thirds said they had experienced at least one rape or sexual assault, including attempts. The researchers, Melanie Randall and Lori Haskell (1995, p. 22), concluded that “it is more common than not for a woman to have an experience of sexual assault during their lifetime.”

Studies of college students also find a high amount of rape and sexual assault. About 20–30 percent of women students in anonymous surveys report being raped or sexually assaulted (including attempts), usually by a male student they knew beforehand (Fisher, Cullen, & Turner, 2000; Gross, Winslett, Roberts, & Gohm, 2006). Thus at a campus of 10,000 students of whom 5,000 are women, about 1,000–1,500 women will be raped or sexually assaulted over a period of four years, or about 10 per week in a four-year academic calendar.

Sexual violence is particularly difficult to track because it is severely under reported. Records from police and government agencies are often incomplete or limited. Most victims of sexual violence do not report it because they are ashamed, afraid of being blamed, concerned about not being believed, or are simply afraid to relive the event by reporting it. Most countries and many NGOs are undertaking efforts to try to increase the reporting of sexual violence as it so obviously has serious physical and psychological impacts on its victims.

The public image of rape is of the proverbial stranger attacking a woman in an alleyway. While such rapes do occur, most rapes actually happen between people who know each other. A wide body of research finds that 60–80 percent of all rapes and sexual assaults are committed by someone the woman knows, including husbands, ex-husbands, boyfriends, and ex-boyfriends, and only 20–35 percent by strangers (Barkan, 2012). A woman is thus two to four times more likely to be raped by someone she knows than by a stranger.

Rape Culture

Language, norms, and everyday behaviors contribute to a culture that permits sexual violence. Sexual violence is normalized through environments that promote an unequal distribution of power and value toxic masculinity. From these environments springs rape culture, which justifies, naturalizes, and may glorify sexual pressure, coercion, and violence (Marcus 1992; Pascoe and Hollander 2016). Rape culture facilitates sexual assault and is perpetuated through the presence of persistent gender inequalities and attitudes about gender and sexuality. As you learned in Chapter 9, gender norms organize social institutions in our society, including power structures and institutional discrimination. Sexuality works to structure our world similarly.

One way rape culture is normalized is through displays of sexual violence in popular culture. Campaigns and advertisements are meant to grab attention, but is there a point at which they can go too far? View the images in the picture below. What messages are being conveyed about bodies, gender relations, and consent in these Dolce & Gabbana ads? How do these messages shape our culture?

Left: A woman in black outfit and high heels lays on the ground while a shirtless man in sunglasses crouches over her and holds down her arms. Three men, one shirtless, one with an unbuttoned shirt watch. Center: Topless man with bare legs exposed lays on floor arching back. Man in white unbuttoned shirt stands next to him unzipping his white pants. Three men are in the background, two are watching the naked man, one is looking away fixing his tie. Right: A woman in a white top and skirt lays on a tiled floor while men and women crouch over her body. One man with an open shirt watches from the background.

A series of ads from Dolce and Gabbana that have since been banned in some countries. They explicitly depict sexual violence in several ways.

The ideas and norms that are part of rape culture also serve as barriers to reporting sexual violence. In U.S. culture, there is a great deal of uncertainty around the types of consequences perpetrators of sexual violence will experience. Influenced by how the media portrays such cases, people may not report incidents of sexual violence due to fears of not being believed. Concerns include doubts about men’s ability to control themselves, mistrust in authority figures’ responses, embarrassment, self-blame, and lack of support from others. These fears create barriers for survivors seeking help and justice.

Explaining Rape and Sexual Assault

Sociological explanations of rape fall into cultural and structural categories similar to those presented earlier for sexual harassment. Various “rape myths” in our culture support the absurd notion that women somehow enjoy being raped, want to be raped, or are “asking for it” (Franiuk, Seefelt, & Vandello, 2008). One of the most famous scenes in movie history occurs in the classic film Gone with the Wind, when Rhett Butler carries a struggling Scarlett O’Hara up the stairs. She is struggling because she does not want to have sex with him. The next scene shows Scarlett waking up the next morning with a satisfied, loving look on her face. The not-so-subtle message is that she enjoyed being raped.

A related cultural belief is that women somehow ask or deserve to be raped by the way they dress or behave. If she dresses attractively or walks into a bar by herself, she wants to have sex, and if a rape occurs, well, then, what did she expect? In the award-winning film The Accused, based on a true story, actress Jodie Foster plays a woman who was raped by several men on top of a pool table in a bar. The film recounts how members of the public questioned why she was in the bar by herself if she did not want to have sex and blamed her for being raped.

A third cultural belief is that a man who is sexually active with a lot of women is a stud and thus someone admired by his male peers. Although this belief is less common in this day of AIDS and other STDs, it is still with us. A man with multiple sex partners continues to be the source of envy among many of his peers. At a minimum, men are still the ones who have to “make the first move” and then continue making more moves. There is a thin line between being sexually assertive and sexually aggressive (Kassing, Beesley, & Frey, 2005).

These three cultural beliefs—that women enjoy being forced to have sex, that they ask or deserve to be raped, and that men should be sexually assertive or even aggressive—combine to produce a cultural recipe for rape. Although most men do not rape, the cultural beliefs and myths just described help account for the rapes that do occur. Recognizing this, the contemporary women’s movement began attacking these myths back in the 1970s, and the public is much more conscious of the true nature of rape than a generation ago. That said, much of the public still accepts these cultural beliefs and myths, and prosecutors continue to find it difficult to win jury convictions in rape trials unless the woman who was raped had suffered visible injuries, had not known the man who raped her, and/or was not dressed attractively (Levine, 2006).

Structural explanations for rape emphasize the power differences between women and men similar to those outlined earlier for sexual harassment. In societies that are male dominated, rape and other violence against women is a likely outcome, as they allow men to demonstrate and maintain their power over women. Supporting this view, studies of preindustrial societies and of the fifty states of the United States find that rape is more common in societies where women have less economic and political power (Baron & Straus, 1989; Sanday, 1981). Poverty is also a predictor of rape; although rape in the United States transcends social class boundaries, it does seem more common among poorer segments of the population than among wealthier segments, as is true for other types of violence (Truman & Rand, 2010). Scholars think the higher rape rates among the poor stem from poor men trying to prove their “masculinity” by taking out their economic frustration on women (Martin, Vieraitis, & Britto, 2006).

Reducing Rape and Sexual Assault

As we have seen, gender inequality manifests itself in many ways, one being in the form of violence against women. A sociological perspective tells us that cultural myths and economic and gender inequality help lead to rape, and that the rape problem goes far beyond a few psychopathic men who rape women. A sociological perspective thus tells us that our society cannot just stop at doing something about these men. Instead it must make more far-reaching changes by changing people’s beliefs about rape and by making every effort to reduce poverty and to empower women. This last task is especially important, for, as Randall and Haskell (1995, p. 22) observed, a sociological perspective on rape “means calling into question the organization of sexual inequality in our society.” To put it in other words, solving the problem of rape is NOT about controlling the men who do it – it’s about making structural changes in society. Just as many other issues, rape is not an individual problem, it’s a systemic one.

Aside from this fundamental change, other remedies, such as additional and better funded rape-crisis centers, would help women who experience rape and sexual assault. Yet even here women of color face an additional barrier. Because the antirape movement was begun by white, middle-class feminists, the rape-crisis centers they founded tended to be near where they live, such as college campuses, and not in the areas where women of color live, such as inner cities and Indigenous people reservations. This meant that women of color who experienced sexual violence lacked the kinds of help available to their white, middle-class counterparts (Matthews, 1989), and despite some progress, this is still true today.

People Making a Difference - College Students Protest against Sexual Violence'

Dickinson College is a small liberal-arts campus in the small town of Carlisle, Pennsylvania. But in the fight against sexual violence, it loomed huge in March 2011, when up to 150 students conducted a nonviolent occupation of the college’s administrative building for three days to protest rape and sexual assault on their campus. While they read, ate, and slept inside the building, more than 250 other students held rallies outside, with the total number of protesters easily exceeding one-tenth of Dickinson’s student enrollment. The protesters held signs that said “Stop the silence, our safety is more important than your reputation” and “I value my body, you should value my rights.” One student told a reporter, “This is a pervasive problem. Almost every student will tell you they know somebody who’s experienced sexual violence or have experienced it themselves.”

Feeling that college officials had not done enough to help protect Dickinson’s women students, the students occupying the administrative building called on the college to set up an improved emergency system for reporting sexual assaults, to revamp its judicial system’s treatment of sexual assault cases, to create a sexual violence prevention program, and to develop a new sexual misconduct policy.

Rather than having police or security guards take the students from the administrative building and even arrest them, Dickinson officials negotiated with the students and finally agreed to their demands. Upon hearing this good news, the occupying students left the building on a Saturday morning, suffering from a lack of sleep and showers but cheered that they had won their demands. A college public relations official applauded the protesters, saying they “have indelibly left their mark on the college. We’re all very proud of them.” On this small campus in a small town in Pennsylvania, a few hundred college students had made a difference.

Sources: Jerving, 2011; Pitz, 2011Jerving, S. (2011, March 4). Pennsylvania students protest against sexual violence and administrators respond. The Nation. Retrieved from http://www.thenation.com/blog/159037...rators-respond; Pitz, M. (2011, March 6). Dickinson College to change sexual assault policy after sit-in. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved from http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/11065...02-1130454.stm

Movements for Change

Feminism

One of the underlying issues that continues to plague women in the United States is misogyny. This is the hatred of or, aversion to, or prejudice against, women. Over the years misogyny has evolved as an ideology that men are superior to women in all aspects of life. This is tied to the idea of patriarchy, or male domination of society. In a patriarchal society characteristics associated with men and masculinity have more power and authority and women are ranked lower than men. Even the valued supposed characteristics of women, such as empathy, nurturance, and care for others, are ranked lower. Men and boys are held in higher social regard than women and girls and are granted additional advantages and rights.

There have been multiple movements to try and fight these ideas. Feminism argues that women and men should have equal legal and political rights. The movement advocates for economic, political, and social equality regardless of the sex one is assigned at birth. It also argues that the systematic oppression of people based on gender is problematic and should be changed.

There have been several “waves” of feminism in US history. The first wave was the suffrage movement, organized to get women the right to vote. It lasted from the 1800s–1920s. However, legally achieving the right to vote did not mean feminism had achieved the goal of equality.

The second wave was fueled by activism centered on gaining equal access to education and employment for women and in general make possible women’s participation in all aspects of American life and to gain for them all the rights enjoyed by men.

Feminists engaged in protests and actions designed to bring awareness and change. For example, the New York Radical Women demonstrated at the 1968 Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City to bring attention to the contest’s—and society’s—exploitation of women. The protestors tossed instruments of women’s oppression, including high-heeled shoes, curlers, girdles, and bras, into a “freedom trash can.” News accounts incorrectly described the protest as a “bra burning,” which at the time was a way to demean and trivialize the issue of women’s rights (Gay 2018).

Other protests gave women a more significant voice in a male-dominated social, political, and entertainment climate. For decades, Ladies Home Journal had been a highly influential women’s magazine, managed and edited almost entirely by men. Men even wrote the advice columns and beauty articles. In 1970, protesters held a sit-in at the magazine’s offices, demanding that the company hire a woman editor-in-chief, add women and non-White writers at fair pay, and expand the publication’s focus.

Feminists in the 1970s also opened battered women’s shelters and successfully fought for protection from employment discrimination for pregnant women, reform of rape laws (such as the abolition of laws requiring a witness to corroborate a woman’s report of rape), criminalization of domestic violence, and funding for schools that sought to counter sexist stereotypes of women. In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court in Roe v. Wade invalidated a number of state laws under which abortions obtained during the first three months of pregnancy were illegal. This made a nontherapeutic abortion a legal medical procedure nationwide.

Many advances in women’s rights were the result of women’s greater engagement in politics. For example, Patsy Mink, the first Asian American woman elected to Congress, was the co-author of the Education Amendments Act of 1972, Title IX of which prohibits sex discrimination in education.

The involvement of more women outside the home transformed feminism. It was no longer just about women as a single group. Feminism began to encompass diverse topics such as women and civil rights, women and work, and women and rural labor, among others. By the 1990s, feminism had consolidated as a social movement with a global reach. These years marked the end of the second wave and the beginning of the third. A different conceptual framework emerged to change how we understand grassroots feminism and its diversification, including queer theory.

The third wave (1990s-2008) emerged out of the feminist criticisms that the first two waves primarily focused on the needs of women who were mostly White and middle class. Previous feminist movements often marginalized and overlooked the concerns of women of color, lesbians, and working-class individuals. One of the goals we see in the third wave is to work toward social justice and equity along the lines of race, social class, sex, gender, and sexuality. By centering the experiences of women of color, the third wave is also concerned with globalization and women’s rights in all countries, as well as the concept of intersectionality.

However, third wave feminism’s focus on identity and the blurring of boundaries did not effectively address many persistent macrosociological issues such as sexual harassment and sexual assault, which will become a focus of fourth wave feminists.

The fourth and current wave of feminism maintains a focus on intersectionality and empowering women by removing the stigma associated with experiences with sexual harassment, body shaming, and rape culture. Social media and the internet play important roles in building awareness around social injustices, particularly through internet activism. The fourth wave critically examines gender norms and the marginalization of women, while seeking gender equity.

During this wave, social media has offered women an opportunity to speak up and share their experiences with sexual harassment, sexual violence, and sexism in the workplace. Within a matter of seconds, the internet provided a tool for women to speak freely about topics in their own words.

Accusations against men in powerful positions—from Hollywood directors to Supreme Court justices to the president of the United States, have catalyzed feminists in a way that appears to be fundamentally different from previous movements. We can already see the impact of this movement on some laws. Initially, some states banned nondisclosure agreements that cover sexual harassment and expanded protections for workers that are not covered by federal sexual harassment and state laws, such as independent contractors (North 2019). The passing of the Speak Out Act in 2022 prohibits the enforcement of non-disclosure agreements when there are allegations of workplace sexual harassment or sexual assault as a way to provide increased options for people to bring their claims in court.

Will the next generation of activists help us move into the fifth wave of feminism? How might this movement intertwine with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade in June 2022? How will leaders of a new movement continue to draw on the work of their predecessors? Time will tell.

Women and Politics

One of the most important places for women to help other women is in politics. Historically in the United States, like many other institutions, political representation has been mostly made up of White men. By not having women in government, their issues are being decided by people who don’t share their perspective. The number of women elected to serve in Congress has increased over the years, but does not yet accurately reflect the general population. In 2021, the population of the United States was 49 percent male and 51 percent female (Census.gov 2022), but the population of Congress was 72.3 percent male and 27.7 percent female (Manning 2022). Until the number of women in the federal government accurately reflects the population, there will be inequalities in our laws.

Women’s bodies are often brought into political conversations. Often, decisions are made regarding what is appropriate for women with little feedback from the group that is directly affected. For example, there is the issue of abortion, and the recent court decision that greatly affects some women’s decision-making abilities today.

On June 24, 2022, in a 6-to-3 decision, the Supreme Court overturned the Roe v. Wade ruling that protected women’s autonomy to choose abortion. The due process clause added to the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution that provided a “right to privacy” and protected pregnant women’s rights to an abortion has changed. This decision comes at a time when data from the PEW Research Center shows that 61 percent of adults believe that abortion should be legal in all or most cases (Pew Research Center 2022a, 2022b).

States where the right to an abortion is not restricted, is restricted, or is completely banned. What do restrictions look like in your state? Image description: https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/soceveryday1e/back-matter/image-descriptions/#oofig9-21

A decision made by nine individuals appointed by a handful of (male) presidents impacts the lives of families and fundamentally restricts women’s autonomy and choices. Now, individual states and government officials have the power to determine women’s reproductive rights. Current laws and policies within individual states will make accessing safe medical procedures difficult. Several states already had laws banning abortion that predated Roe v. Wade, and others had trigger laws (bans on abortion that would go into effect with the overturning of Roe v. Wade) (Mangan 2022a). Some states have bans on abortions after six weeks of gestation. At such an early stage, many women might not be aware that they are pregnant. Others might not be able to secure doctor’s appointments within the narrow timeframe.

Justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett, argued that the 1973 ruling was an error made on weak arguments and an “abuse of judicial authority” (Totenberg and McCammon 2022). Dissenting Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan said that the court decision means that “young women today will come of age with fewer rights than their mothers and grandmothers . . . from the very moment of fertilization, a woman has no rights to speak of. A state can force her to bring a pregnancy to term even at the steepest personal and familial costs” (Totenberg and McCammon 2022). This ruling has significant implications for women’s positions in society—or at least for some women. Affluent women have always and will continue to have options when it comes to seeking medical care.

There are many reasons a woman may choose to get an abortion. Rather than questioning why someone might want control over their reproductive rights and bodies, it is interesting from a sociological perspective to understand how complicated this court decision becomes when we examine our current social institutions. As the dissenting justices pointed out, women will be expected (and can be forced) to carry pregnancies to term when our current work and family policies do not uniformly support family life.

In the United States, parental leave policies are limited. If workplaces offer parental leave, it is often unpaid. This can either create an additional financial burden or make time off inaccessible at a time when new parents and guardians need to adjust to the mental and physical demands that come with newborns. If eligible, employees may need to take short-term disability or use the Family and Medical Leave Act. Government programs like Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) attempt to offer financial support for low-income families with children, but there is still a stigma associated with participating in welfare programs (McLaughlin 2021). Eligibility requirements are restrictive and benefits are low. For example, in Oregon the current maximum monthly benefit for a family of three is $503. We also should consider how this decision will impact the growing fertility industry.

Keep in mind that this discussion is intended to point out how women’s rights are now restricted. This decision disproportionately affects women of color and those with lower socioeconomic status (Dehlendorf, Harris, and Weitz 2013; Johnson 2022). The overturning of Roe v. Wade also brings into question other rulings where it was used as precedent. For example, Justice Clarence Thomas has mentioned that we need to reexamine marriage equality and contraceptive rights (Mangan 2022b). This single court decision demonstrates that gender organizes our daily lives, from how we learn to interact with others to how our laws serve to protect us.

Benefits and Costs of Being Male in a Sexist Society

Most of the discussion so far has been about women, and with good reason: In a sexist society such as our own, women are the subordinate, unequal sex. But gender means more than female, and a few comments about men are in order.

Benefits

We have already discussed gender differences in occupations and incomes that favor men over women. In a patriarchal society, men have more wealth than women and more influence in the political and economic worlds more generally.

Men profit in other ways as well. We’ve talked about white privilege, or the advantages that whites automatically have in a racist society whether or not they realize they have these advantages. Many scholars also talk about male privilege, or the advantages that males automatically have in a patriarchal society whether or not they realize they have these advantages (McIntosh, 2007).

A few examples illustrate male privilege. Men can usually walk anywhere they want or go into any bar they want without having to worry about being raped or sexually harassed. Susan Griffin was able to write “I have never been free of the fear of rape” because she was a woman; it is no exaggeration to say that few men could write the same thing and mean it. Although some men are sexually harassed, most men can work at any job they want without having to worry about sexual harassment. Men can walk down the street without having strangers make crude remarks about their looks, dress, and sexual behavior. Men can ride the subway system in large cities without having strangers grope them, flash them, or rub their bodies against them. Men can apply for most jobs without worrying about being rejected because of their gender, or, if hired, not being promoted because of their gender. More examples of male privilege are given below

- If you have a bad day or are in a bad mood, people aren’t going to blame it on your gender.

- You can be careless with your money and not have people blame it on your gender.

- You can be a careless driver and not have people blame it on your gender.

- You can be confident that your coworkers won’t assume you were hired because of your gender.

- You can expect to be paid equitably for the work you do and not paid less because of your gender.

- If you are unable to succeed in your career, that won’t be seen as evidence against your gender in the workplace.

- A decision to hire you won’t be based on whether the employer assumes you will be having children in the near future.

- You can decide not to have children and not have your masculinity questioned.

- If you choose to have children, you will be praised for caring for your children instead of being expected to be the full-time caretaker.

- You can balance a career and a family without being called selfish for not staying at home (or being constantly pressured to stay at home).

- If you are straight and decide to have children with your partner, you can assume this will not affect your career.

- If you rise to prominence in an organization/role, no one will assume it is because you slept your way to the top.

- You can seek political office without having your gender be a part of your platform.

- You can seek political office without fear of your relationship with your children, or whom you hire to take care of them, being scrutinized by the press.

- Most political representatives share your gender, particularly the higher-ups.

- Your political officials fight for issues that pertain to your gender, or at least don’t dismiss your issues as “special interest.”

- You can ask for the “person in charge” and will likely be greeted by a member of your gender.

- As a child, you were able to find plenty of non-limiting, non-gender-role-stereotyped media to view.

- You can disregard your appearance without worrying about being criticized at work or in social situations.

- You can spend time on your appearance without being criticized for upholding unhealthy gender norms.

- If you’re not conventionally attractive (or in shape), you don’t have to worry as much about it negatively affecting your social or career potential.

- You’re not expected to spend excessive amounts of money on grooming, style, and appearance to fit in, while making less money.

- You can have promiscuous sex and be viewed positively for it.

- You can go to a car dealership or mechanic and assume you’ll get a fair deal and not be taken advantage of.

- Colloquial phrases and conventional language reflect your gender (e.g., mailman, “all men are created equal”).

- Every major religion in the world is led by individuals of your gender.

- You can practice religion without subjugating yourself or thinking of yourself as less because of your gender.

- You are unlikely to be interrupted in conversations because of your gender.

Adapted from https://www.itspronouncedmetrosexual.com/2012/11/30-examples-of-male-privilege/

Costs

Yet it is also true that men pay a price for living in a patriarchy. Without trying to claim that men have it as bad as women, scholars are increasingly pointing to the problems men face in a society that promotes male domination and traditional standards of masculinity such as assertiveness, competitiveness, and toughness (Kimmel & Messner, 2010). Socialization into masculinity is thought to underlie many of the emotional problems men experience, which stem from a combination of their emotional inexpressiveness and reluctance to admit to, and seek help for, various personal problems (Wong & Rochlen, 2005). Sometimes these emotional problems build up and explode, as mass shootings by males at schools and elsewhere indicate, or express themselves in other ways. Compared to girls, for example, boys are much more likely to be diagnosed with emotional disorders, learning disabilities, and attention deficit disorder, and they are also more likely to commit suicide and to drop out of high school.

Men experience other problems that put themselves at a disadvantage compared to women. They commit much more violence than women do and, apart from rape and sexual assault, also suffer a much higher rate of violent victimization. They die earlier than women and are injured more often. Because men are less involved than women in child rearing, they also miss out on the joy of parenting that women are much more likely to experience.

Growing recognition of the problems males experience because of their socialization into masculinity has led to increased concern over what is happening to American boys. Citing the strong linkage between masculinity and violence, some writers urge parents to raise their sons differently in order to help our society reduce its violent behavior (Corbett, 2011). In all these respects, boys and men—and our nation as a whole—are also paying a price for living in a patriarchal society.

Reducing Gender Inequality

Gender inequality is found in varying degrees in most societies around the world, and the United States is no exception. Just as racial/ethnic stereotyping and prejudice underlie racial/ethnic inequality, so do stereotypes and false beliefs underlie gender inequality. Although these stereotypes and beliefs have weakened considerably since the 1970s thanks in large part to the contemporary women’s movement, they obviously persist and hamper efforts to achieve full gender equality.

A sociological perspective reminds us that gender inequality stems from a complex mixture of cultural and structural factors that must be addressed if gender inequality is to be reduced further than it already has been since the 1970s. Despite changes during this period, children are still socialized from birth into traditional notions of femininity and masculinity, and gender-based stereotyping incorporating these notions still continues. Although people should certainly be free to pursue whatever family and career responsibilities they desire, socialization and stereotyping still combine to limit the ability of girls and boys and women and men alike to imagine less traditional possibilities. Meanwhile, structural obstacles in the workplace and elsewhere continue to keep women in a subordinate social and economic status relative to men.

To reduce gender inequality, then, a sociological perspective suggests various policies and measures to address the cultural and structural factors that help produce gender inequality. These steps might include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Reduce socialization by parents and other adults of girls and boys into traditional gender roles.

- Confront gender stereotyping by the popular and news media.

- Increase public consciousness of the reasons for, extent of, and consequences of rape and sexual assault, sexual harassment, and pornography.

- Increase enforcement of existing laws against gender-based employment discrimination and against sexual harassment.

- Increase funding of rape-crisis centers and other services for girls and women who have been raped and/or sexually assaulted.

- Increase government funding of high-quality day-care options to enable parents, and especially mothers, to work outside the home if they so desire, and to do so without fear that their finances or their children’s well-being will be compromised.

- Increase mentorship and other efforts to boost the number of women in traditionally male occupations and in positions of political leadership.

As we consider how best to reduce gender inequality, the impact of the contemporary women’s movement must be neither forgotten nor underestimated. Since it began in the late 1960s, the women’s movement has generated important advances for women in almost every sphere of life. Brave women (and some men) challenged the status quo by calling attention to gender inequality in the workplace, education, and elsewhere, and they brought rape and sexual assault, sexual harassment, and domestic violence into the national consciousness. For gender inequality to continue to be reduced, it is essential that a strong women’s movement continue to remind us of the sexism that still persists in American society and the rest of the world.

References

Begley, S. (2009, September 14). Pink brain, blue brain: Claims of sex differences fall apart. Newsweek, 28.

Eliot, L. (2011). Pink brain, blue brain: How small differences grow into troublesome gaps—and what we can do about it. London, United Kingdom: Oneworld Publications.

Hesse-Biber, S. N. (2007). The cult of thinness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; Milillo, D. (2008). Sexuality sells: A content analysis of lesbian and heterosexual women’s bodies in magazine advertisements. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 12(4), 381–392.

Tanenbaum, L. (2009). Taking back God: American women rising up for religious equality. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Mayer, A. E. (2009). Review of “Women, the Koran and international human rights law: The experience of Pakistan.” Human Rights Quarterly, 31(4), 1155–1158.

Lindsey, L. L. (2011). Gender roles: A sociological perspective (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Jacobs, Sue-Ellen, Wesley Thomas, and Sabine Lang. 1997. Two Spirit People: Native American Gender Identity, Sexuality, and Spirituality. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Poasa, Kris. 1992. “The Samoan Fa’afafine: One Case Study and Discussion of Transsexualism.” Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality 5(3):39–51.

Flores, Andrew R. and Herman Jody L. and Gates, Gary J. and Taylor, N.T. Brown. "How Many Adults Identify As Transgender In The United States?" The Williams Institute. June 2016. (https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Trans-Adults-US-Aug-2016.pdf)

Sears, Brad, Castleberry, Neko Michelle, Lin, Andy, and Mallory, Christy. “LGBTQ People’s Experiences of Workplace Discrimination and Harassmen.t” The Williams Institute. August 2024. (https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.e...iscrimination/)

Sears, Brad. “Impact of Executive Order Revoking Non-Discrimination Protections for LGBTQ Federal Employees and Employees of Federal Contractors.” The Williams Institute. January 2025. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/impact-eo-nd-federal-workers/

GLAAD. 2021. "Tips for Allies of Transgender People." GLAAD.org. Retrieved April 12, 2021. (https://www.glaad.org/transgender/allies)

UCSF Transgender Care. 2019. "Transition Roadmap." University of California San Francisco Transgender Care. Retrieved April 15 2021 (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/transition-roadmap)

TSER. 2021. "Definitions." Trans Student Educational Resources. Retrieved April 15 2021. (https://transstudent.org/about/definitions/)

American Psychological Association (APA). 2023. “Understanding transgender people, gender identity and gender expression.” Washington, DC. Retrieved March 20 2025. (https://www.apa.org/topics/lgbtq/transgender-people-gender-identity-gender-expression).

interACT. 2021. "FAQ: What Is Intersex." InterACT Advocates for Intersex Youth. January 26, 2021. (https://interactadvocates.org/faq/#)

Koyama, Emi. n.d. "Adding the "I": Does Intersex Belong in the LGBT Movement?" Intersex Initiative. Retrieved April 15, 2021. (http://www.intersexinitiative.org/articles/lgbti.html)

Behrens, K.G. 2020. "A principled ethical approach to intersex paediatric surgeries. BMC Med Ethics 21, 108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-00550-x

TSER. 2021. "Definitions." Trans Student Educational Resources. Retrieved April 15 2021. (https://transstudent.org/about/definitions/)

Mayo Clinic. 2021. "Children and gender identity: Supporting your child." Mayo Clinic Staff. January 16 2021. (https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/childrens-health/in-depth/children-and-gender-identity/art-20266811)

Zaliznyak, M., Bresee, C., & Garcia, M. M. 2020. "Age at First Experience of Gender Dysphoria Among Transgender Adults Seeking Gender-Affirming Surgery." JAMA network open, 3(3), e201236. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1236

Widmer, Eric D., Judith Treas, and Robert Newcomb. 1998. “Attitudes Toward Nonmarital Sex in 24 Countries.” Journal of Sex Research 35(4):349.

PFLAG. 2021. "PFLAG National Glossary of Terms." PGLAG.org. Retrieved April 12 2021. (https://pflag.org/glossary)

Asexual Visibility and Education Network. 2021. "The Gray Area." Retrieved April 12, 2021. (https://www.asexuality.org/?q=grayarea)

UC Davis LGBTQIA Resource Center. 2020. "LGBTQIA Resource Center Glossary." January 14 2020. ( https://lgbtqia.ucdavis.edu/educated/glossary)

Tompkins, Chris. 2017. "Why Heteronormativity Is Harmful." Learning for Justice. July 18, 2017. (https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/why-heteronormativity-is-harmful)

Boyer, S. J., and Lorenz, T. K. 2020. "The impact of heteronormative ideals imposition on sexual orientation questioning distress." Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 7(1), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000352

American Psychological Association (APA). 2008. “Answers to Your Questions: For a Better Understanding of Sexual Orientation and Homosexuality.” Washington, DC. Retrieved January 10, 2012 (http://www.apa.org/topics/sexuality/orientation.aspx).

Calzo JP, and Blashill AJ. 2018. "Child Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Cohort Study." JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(11):1090–1092. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2496

Kinsey, Alfred C. et al. 1998 [1948]. Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Sedgwick, Eve. 1985. Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire. New York: Columbia University Press.

Mills-Koonce, W. R. and Rehder, P. D. and McCurdy, A. L. 2018. "The Significance of Parenting and Parent-Child Relationships for Sexual and Gender Minority Adolescents." Journal of research on adolescence : the official journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence, 28(3), 637–649. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12404

Human Rights Watch. 2020. "Anti-LGBT Persecution in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras." Human Rights Watch. October 7 2020. (https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/07/...emala-honduras)

ILGA World: Lucas Ramon Mendos, Kellyn Botha, Rafael Carrano Lelis, Enrique López de la Peña, Ilia Savelev and Daron Tan, State-Sponsored Homophobia 2020: Global Legislation Overview Update Geneva: ILGA, December 2020.

Foglia, M. B., & Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I. 2014. "Health Disparities among LGBT Older Adults and the Role of Nonconscious Bias." The Hastings Center report, 44 Suppl 4(0 4), S40–S44. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.369

American Heart Association. 2020. "Discrimination contributes to poorer heart health for LGBTQ adults." October 8 2020. (https://newsroom.heart.org/news/discrimination-contributes-to-poorer-heart-health-for-lgbtq-adults)

Herek, G. M. 1990. “The Context of Anti-Gay Violence: Notes on Cultural and Psychological Heterosexism." Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 5: 316–333.

Gender-Inclusive Biology. "Language Guide." Retrieved April 15 2021 (https://www.genderinclusivebiology.com/bettersciencelanguage)

Canadian Public Health Association. 2019. "Language Matters: Using respectful language in relation to sexual health, substance use, STBBIs and intersecting sources of stigma." Retrieved April 15 2021. (https://www.cpha.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/resources/stbbi/language-tool-e.pdf)

Caldera, Yvonne, Aletha Huston, and Marion O’Brien. 1998. “Social Interactions and Play Patterns of Parents and Toddlers with Feminine, Masculine, and Neutral Toys.” Child Development 60(1):70–76.

Kimmel, Michael. 2000. The Gendered Society. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Lindsey, L. L. (2011). Gender roles: A sociological perspective (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Ready, Diane. 2001. “‘Spice Girls,’ ‘Nice Girls,’ ‘Girlies,’ and ‘Tomboys’: Gender Discourses, Girls’ Cultures and Femininities in the Primary Classroom.” Gender and Education 13(2):153-167.

Coltrane, Scott, and Michele Adams. 2008. Gender and Families Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Gerdeman, Dina. 2019. "How Gender Stereotypes Can Kill a Woman's Self-Confidence." Harvard Business School. Working Knowledge. February 25 2019. (https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/how-gender-stereotypes-less-than-br-greater-than-kill-a-woman-s-less-than-br-greater-than-self-confidence)

Bygren, Magnus and Erlandsson, Anni and Gähler, Michael. 2017. "Do Employers Prefer Fathers? Evidence from a Field Experiment Testing the Gender by Parenthood Interaction Effect on Callbacks to Job Applications." European Sociological Review, Volume 33, Issue 3, June 2017, Pages 337–348, https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcx051

Ogden, Lesley Evans. 2019. "Working Mothers Face a 'Wall' of Bias, But There Are Ways to Push Back." Science Magazine. April 10 2019. (https://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2019/04/working-mothers-face-wall-bias-there-are-ways-push-back)