1.8: The Southwest

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 142171

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

As related in oral histories, the Puebloan people did not disappear—they simply moved, sometimes covering hundreds of kilometers during their migrations. And, for many Pueblo people today, the places they left today are considered sacred homelands, their points of origin.

—John Kantner, Ancient Puebloan Southwest, p. 195

When people think of the American Southwest, images of pottery, maize, and pueblos come to mind. But if we look at the archaeological record, we see that these features so characteristic of the Southwest today, weren’t always there. The Paleoindian Period (ca. 13,500—8,000 B.P.) which we discussed in Chapter 4 is the earliest known occupation of the Southwest. The time period following the Paleoindian period is called the Archaic period. The term “Archaic” is equivalent to the Mesolithic in Europe (Chapter 6). As with the Mesolithic, the Archaic does not represent a single ethnic or linguistic group, but rather, it refers to a subsistence strategy and architectural style. The Archaic period in the Southwest (ca. 8,000 .P.–1,500 B.P.) was characterized by semi-mobile/semi-sedentary hunter-gatherers. Late in the Archaic, people began incorporating maize into their diets and practicing a mixture of farming and foraging (see Chapter 5).

From ca. 200 BC to AD 700, people in the Southwest were living in farming villages in structures called pithouses, which are houses partially excavated into the ground. By this time, people were growing maize, squash, and beans, and likely moved between the growing seasons in order to hunt and gather foods, since crops could not be grown year-round. Ceramics appear in the archaeological record in the Southwest around AD 200 and become common around AD 500.

Three Traditions

After AD 700, three southwestern archaeological traditions that relied on agriculture emerged. These are called Hohokam, Mogollon and Ancestral Pueblo (formerly called Anasazi). These groupings refer to similarities in material culture, notably pottery, architecture, and burial customs, and not necessarily to ethnic identities. Considerable variation existed within each of these traditions and their boundaries were in no way fixed. All agriculturalists of the Southwest relied on maize as the basis of their subsistence system. As at Neolithic sites in the Near East, there is an abundance of ground

stone in the Southwest for grinding maize into flour, testifying to the reliance on maize as a staple crop. These tools are called manos (the smaller stone held in the hand) and metates(the basin stone) and become larger and increasingly more elaborate as reliance on maize intensified. As you can see from the map, the term Southwest is not very accurate since it comprises a large portion of Northwest Mexico as well as the American Southwest. While we tend to think in terms of modern nation-borders, there was no boundary between Mexico and the United States in prehistory. For this reason, archaeologist Randall McGuire refers to the region as the Southwest-Northwest. In this chapter, we will focus on the agricultural periods, and three key sites/regions: Snaketown (Hohokam); Chaco Canyon (Ancestral Pueblo); and the Mimbres region (Mogollon). Manos and Metates for grinding maize.

The Hohokam

The Hohokam culture area was located in the Sonoran Desert of southern Arizona, Sonora, and Chihuahua, but centered in the Salt-Gila River Valley in Arizona. The name comes from the indigenous O’odham inhabitants of the region and translates as “all used up” (huhugam). The descendants of the Hohokam are likely the O’odham, and the ancient Hohokam figure into O’odham oral histories (Donald Bahr in Fish and Fish 2007:123).

Many Hohokam sites are now under modern-day Phoenix. The Hohokam tradition is characterized by red-on-buff pottery, architecture, cremation burials, and irrigation system. This long-lived tradition (AD-450–1450) has been dubbed by archaeologists Suzanne and Paul Fish the Hohokam millennium (AD-450–1450). Changes in material culture and architecture occurred during this long span of time, and not every Hohokam site had every feature of Hohokam society.

The Hohokam hunted rabbits and deer and cultivated the Southwestern trio of corn, beans, and squash, which were originally domesticated in Mexico. Corn, beans and squash are sometimes called the Southwestern trio or Three Sisters because they provide benefits to each other. Maize acts as a trellis for the beans to grow on. Beans were a critical component of this trio. Nitrogen is necessary for plant life, and modern fertilizers contain nitrogen that plants can use (Chapter 6, Chemistry in Context). Not all forms of nitrogen can be used by plants. This is where beans come in. The bacteria on the roots of the bean “fix” nitrogen from the atmosphere and convert it to a form that plants can use such as ammonia (NH4+) or the ammonium ion (No3-). Thus beans helped to keep the soil fertile for other plants. The bacteria on the beans are in turn fed by sugars from the corn. Finally, the squash provides protection from the sun with its broad leaves. The Hohokam also grew agave and cotton. Cotton takes a lot of water to grow and the Hohokam may have traded cotton textiles around the Southwest (Doyel 1979). Remnants of cotton clothing have even been found, including a child’s cotton poncho (Crown, in Fish and Fish 2009:25). Children are also visible in the Hohokam record through pottery. Dr. Patty Crown of UNM has argued that paintings on Hohokam and other Southwest pottery bears the mark of inexperienced potters, likely children.

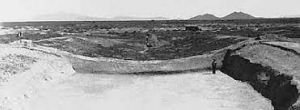

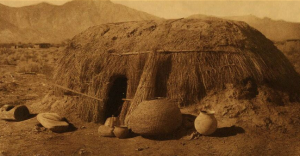

The Hohokam region received so little precipitation, less than is necessary to grow maize, that maize agriculture without canal irrigation would have been impossible. To solve this problem, the Hohokam engineered the largest canal system north of Mexico. Hohokam canals were major undertakings. Some of the canals are up to 12.5 mi. (20 km) in length and can still, be seen today. The largest Hohokam canals were massive—75 feet wide at their widest point and irrigated up 70,000 acres! These canals required skilled engineering as well as labor to produce and maintain. The canal could not be too steep as the rapid flow would erode the channel, while too shallow of a grade would cause build-up. The grade was about 1 or 2 feet per mile, and evidence of water control gates has also been found (Howard). Archaeologists have used equations from engineering to estimate the amount of soil removed to build the canal, the labor to build the canals, the water flowing through the channel, the crops it could have watered, and the number of people it could have supported (Howard). The largest Hohokam villages were populated with around 1,000 or 2,000 people. Today, the Phoenix Basin is one of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the country. Groundwater has lowered more than 500 feet, and many of Arizona’s rivers, like the Gila, are dry or nearly dry. As a consequence of Arizona’s burgeoning population and water problems, a massive canal system diverts water from Colorado to major cities in Arizona. Since the construction of Glen Canyon Dam, the Colorado River, the same one that carved out the Grand Canyon, no longer flows to the sea. Snaketown The heyday of the Hohokam was between AD 700 and 1150, called the Pre-classic period. Snaketown, located in the Phoenix Basin at the confluence of the Gila and Salt rivers some thirty miles southeast of Phoenix, is the largest and best known Hohokam site. Snaketown (AD 1–AD 1150) reached its height in the mid-1000s and might have served as a political-ritual center for smaller outlying settlements. People lived in wattle and daub structures built in shallow pits (a shallow pithouse) and in distinct clusters around a courtyard. Wattle and daub refer to a stick structure covered with clay or soil. These houses may have looked something like O’odham houses (see image). While we tend to think of houses today as something that we spend most of our time in, the Hohokam likely did much of their daily activity in the courtyards. Unlike the Ancestral Pueblo structures, Hohokam structures tend not to be highly visible on the surface.

Larger and better-quality houses were located in the central part of the site, suggesting it was used by higher-ranking individuals. The extent of the social hierarchy of the society at Snaketown is still unclear.

From about AD 550-1100, the Hohokam used a characteristic red-on-buff (light brown) pottery with both geometric and figurative designs. This pottery was shaped by paddling the exterior with a piece of wood, leaving characteristics flattened areas. The Hohokam also had pyrite mirrors, mosaics, birds, and copper bells from western Mexico (Doyel 1979). The Hohokam also made clay figurines of humans and animals. The human figurines show headbands, jewelry, and sometimes ballgame paraphernalia. Decorative bone hairpins have also been uncovered depicting a bird eating a snake (also depicted on Mexico’s flag!). Unlike the Mogollon and Ancestral Pueblos, the Hohokam cremated their dead and placed them in cemeteries. Schist pallets are associated with Hohokam cremations. The figurines coupled with cremations located beneath plazas suggest to research archaeologist Henry Wallace that ancestor veneration was part of the Hohokam belief system (Fish and Fish 2007:19).

Ball Courts

More than 238 Hohokam ball courts have been found (Abbott). Snaketown also contains two ball courts—one being the largest in the Hohokam region. The ball courts reached their greatest extent in the 1000s. Hohokam ballcourts were oval-shaped and defined by curved earthen berms. The Hohokam likely played a version of the Mesoamerican ballgame, a ritualized game associated with fertility, sacrifice, and militarism. The Hohokam were likely playing the “commoner game” version of the ball game, which involved keeping a ball in the air, rather than knocking it through a circular disk (McGuire). Depictions of this game are known from west Mexico. Rubber balls made from the local plant (Guayule) were also discovered in dry caves in the Phoenix area. As with the game of chunkey at Cahokia, the game was likely tied to ritual, and the Hohokam may have hosted a ballgame between villages, and the game may have functioned to integrate Hohokam villages. It is thought that some type of social hierarchy in the form of chiefs would have been necessary to organize the construction and management of the canals, ball courts, and platform mounds (Doyel 1979). And yet, the ball courts were open structures and appear to have served the Hohokam community as opposed to a small cadre of elites.

Snaketown also had low platform mounds made of clean desert sediment, which are found on other Hohokam sites as well. The mounds were built up incrementally and increased in size over time. Their function, however, is unclear but is likely ritual in nature. One mound, Mound 16 at Snaketown, was palisaded. In at least one case, a parrot was buried inside the mound. These mounds may have been inspired by those to the south in northern Mexico. The Hohokam were legendary for their use of shells. If Catalhoyukians were “plaster freaks”, the Hohokam can be considered “shell freaks”. Most notable are the Glycymeris “armlets”, which came from the Gulf of California in western Mexico. Craft specialization means that people make more goods than they use for their own families. Archaeologist Barbara Mills found that Hokokam households located on platform mound compounds made and used more shell items than did households further away from the platform mounds, suggesting that elite households were directly involved in the production and use of craft items. In some cases, whole villages specialized in the production of goods. Los Colinas, a large Hohokam site located at the end of the canal system, appears to have been a major producer of pottery for an entire canal system. This is an example of village-level specialization, in which a village produces goods for an entire group of villages.

After AD 1150 Snaketown and other large settlements were largely abandoned and the population shifted to the Salt River Valley. Some people moved from houses in pits to above-ground adobe structures in walled residential compounds that were tightly clustered. The move may have been influenced by an overall climatic downturn that may have led to the abandonment of Chaco Canyon (see next section). Ball courts declined while more and larger platform mounds with 1 to 30 rooms on top of them were erected (Elson, in Fish and Fish 2007: 52). These were made of river cobbles, trash, adobe, and silt (Elson, in Fish and Fish 2007: 51). These ritual features seemed to have functioned differently than the open ball courts, often being inside a walled compound with restricted access. This more limited access compared to the open ball courts suggests a change in ritual and also increasing social differentiation and inequality.

Critical Thinking Question

After AD 1150, trade and production of palettes along with the characteristic red-on-buff pottery and figurines declined. Around AD 1300 large multi-storied adobe structures called “big houses” like the one at Casa Grande in Arizona were built. During this time, it is thought that social hierarchy, cultivation, and population size increased (Fish and Fish 2007, 9). Large settlements become much larger with between 6,000-10,000 people. After AD 1450, the system of large sites disintegrated, followed by smaller more modest settlements. When Father Kino, a Spanish Jesuit missionary arrived in the region in the 1680s, the people bore little resemblance to the ancient Hohokam.

Ancestral Pueblo

The Ancestral Pueblo (formerly called Anasazi) was located in the Four Corners region of the American Southwest on the Colorado Plateau. They are the best known of the three agricultural traditions in the Southwest because of the spectacular preservation of ruins and artifacts. Perhaps the most famous site in all of New Mexico is Chaco Canyon (ca. AD 850–1150), a World Heritage Site. Chaco Canyon is located in San Juan Basin in northwestern New Mexico. The canyon itself is 9 miles long and has little permanent water and few trees grow in this environment. Chaco Canyon contains 14 great houses—large masonry complexes of several hundred rooms standing as high as four stories. It is estimated that a single room at Pueblo Bonito took as much as 44 tons of sandstone to be cut from the cliffs (Plog 1997:102). The great houses appear to have been built according to a preconceived plan. Each great house also had at least one great kiva—a large semi-subterranean (partially underground) ceremonial room with specialized features such as floor vaults, sipapu, masonry bench, raised firebox, deflector, and attached antechamber—which played a central ceremonial role in community activities, along with several smaller kivas. The sipapu is a hole that represented the point of emergence from the underworld. Great kivas were between 30 and 60 feet in diameter and could be up to six feet deep (Plog 1997: 105).

Large great houses are located mainly on the north side of the canyon. Smaller residential sites, more typical of earlier Ancestral Puebloan pueblos, are located on the south side of the canyon but occupied at the same time as the Great Houses. Pueblo Bonito is the largest of the great houses in Chaco Canyon with 650 rooms. It was built in major, planned construction episodes. Estimates of the population at the site range from a few hundred to a few

thousand. Some suggest building activity at Chaco was related to the supernova of 1054 (SN 1054), the residual of which is the crab nebula (Plog 1997:100). A great house Pueblo Peñasco Blanco, there is a nearby pictograph (painted rock art) of a waning crescent moon and a starburst image, which may represent the supernova. Chaco Canyon is the source of much debate. It is not clear whether the site was residential, with full-time inhabitants, or purely ritual in nature. Few hearths were found in any of the rooms, suggesting little residential activity, but top floors had collapsed and in modern Pueblos, the habitation rooms with hearths are found on upper levels. So, the evidence for habitation may not have preserved the ravages of time.

Chaco Order

The great houses at Chaco are not randomly built. Some have looked at Chacoan architecture and use of space and found commonalities with modern pueblos. Of course, not all pueblos are exactly alike in their cosmology (world order), but some general trends are common. Fritz noticed that most great houses were symmetrical east to west. This may reflect the idea of duality so common modern Rio Grande Pueblo cosmology today. The upper world and under are mirror images of each other, the sun rising in the east and setting in the west in the upper world, the reverse in the underworld. Humans first emerged from the underworld into the upper through a hole in the north. Solstices and equinoxes are an important way to divide up the calendar year, and people may be divided into two groups each responsible for different ceremonies. At Chaco, most of the great houses and circular great kivas are in the north, paralleling the pueblo oral tradition of emergence. The great kivas may be a metaphor for the original point of emergence. There is some suggestion of social power at the site. Room number 33 at Pueblo Bonito contained 14 people. Two of these were buried beneath a wooden floor with hundreds of grave offerings: thousands of turquoise beads, hundreds of turquoise pendants, 40 shell bracelets, a shell trumpet, and a cylinder-shaped basket covered with turquoise that was also filled with turquoise and shell beads. In addition to the 12 people above the wooden floor were turquoise beads and pendants along with shell bracelets, cylinder vessels, carved sticks, and large wooden flutes. “Other individuals buried in nearby rooms were laid to rest on a mat bulrushes and wrapped in feather-cloth robes and cotton fabrics” (Plog 1997:109).

A total of 375 crooked staffs were found in Room 32 at Pueblo Bonito. Shearin reported that crooked sticks were used by Pueblos as symbols of authority and power.

The individuals were 2 inches taller than the average Chacoans with less evidence of anemia, suggesting better nutrition and access to food than the average Chacoan at smaller sites. Deer and antelope bones are also more common at the great houses than at the smaller sites (Plog 1997:109).

Additionally, inside some rooms at Pueblo Bonito and other Chaco great houses were found unusual and rare items such as intricately carved wooden objects, copper bells from Mexico, shell trumpets from the Gulf of California, effigy pottery shaped like humans or animals, turquoise, macaw remains, cylinder jars, and parts of headdresses and altars. Great Houses also occur outside of Chaco; these are called “Chacoan outliers”. The Canyon imported a huge amount of pottery and other commodities from outlying areas. The exact type of relationship between Chaco and these outlying communities is not fully understood.

Chaco Chocolate

Work by Patty Crown on Chaco ceramics is revealing that Chaco had clear ties to Mesoamerica in the form of liquid chocolate which was an item used only by elites. She has found chemical markers for theobromine, an alkaloid in chocolate inside of pottery fragments from cylinder vessels at Pueblo Bonito. Crown currently holds field schools at Chaco Canyon, in historically excavated portions of the site only. New excavations at Chaco

are not possible as modern Pueblo Nations do not want this sacred site disturbed.

Dendrochronology and Wood

Prior to the 1920s and 30s, before tree-ring dating, Southwest archaeologists had a tough time knowing when things happened. They looked at changes in pottery styles at historically known places like Pecos Pueblo east of Santa Fe to get an idea of how pottery styles change over time. Archaeologists knew there were stylistic changes over time because they could see them in the stratigraphy at Pecos Pueblo. They knew, for example, that black-and-white pottery was earlier than more colorful multi-colored, polychrome, pots. Archaeologists used these sequences of changes in pottery styles to estimate dates for sites across the Southwest. Needless to say, it was a huge job.

Tree-ring dating, or dendrochronology, changed all that. Dendrochronology uses the annual growth rings on trees as a dating method. Tree rings were obtained from preserved wooden beams found at archaeological sites. The technique was first applied in the Southwest by A.E. Douglass. Each sequence of tree rings is unique in terms of the varying thickness of the rings because of changes in time in rainfall. If we begin with a modern tree-ring sample (some Bristlecone pines have lived to be 5,000 years or more) and match up the ring pattern with successively older wood samples, we can create a sequence of tree rings widths that go farther and farther back in time. Since each ring represents a year of growth, we can count the rings to get the age of the wood. This is called a calendar date, which is simply an actual date of the wood. Once we have an overall master sequence, archaeologists can compare a sample to this master sequence, and get a date. This technique has been used to check the validity of radiocarbon dating. Importantly, inner rings provide older dates than outer rings, because the inner rings are older than the outer rings. This is called the old wood problem. For this reason, archaeologists like to use short-lived plants, seeds, or twigs when radiocarbon dating a wood sample, otherwise the technique might date the earlier growth of the tree and not the time when it was cut and used by people. Today, tree-ring dates go back about 8,000 years. One of the foremost dendrochronologists and wood specialists in the Southwest, Tom Windes, came to my face-to-face archaeology class in the fall of 2013.

Not only can dendrochronology provide a date estimate, but it can reveal the season in which the tree was cut. The light-colored portion of the ring represents the period of growth in spring and dark rings represent dormancy in winter. The outermost ring indicates the season of cutting. If the outermost ring is light, the tree was cut during its season of growth. Most tree harvesting at Chaco took place during the growing season in the spring/early summer. Tree rings also provide information about climate. Droughts can be seen in smaller sequences of rings and times of relatively high rainfall larger rings. Coupled with tree rings, ancient pollen remains found in ancient packrat middens can also be informative about past climate. These packrat middens or nests are solidified and preserved by a substance called amber, crystallized urine in the nest, and reveal the types of pollen that were in the area at the time. Long records of climate change have been created based on these middens. Needless to say, packrat urine is a very important tool in Southwest archaeology. If you go to the New Mexico Museum of Natural History, you can see a small exhibit on packrat middens.

As wondrous as dendrochronology is, there are some problems. In many cases, wooden beams were reused for generations! This makes dating structures imprecise because house beams might date much earlier than the actual house use. Yet, only about 10 percent of wood at Chaco was recycled—they were wood connoisseurs, or as Ian Hodder might out it, “wood freaks”. Their use of wood was sometimes extravagant. Some kivas, for example, had cribbed roofs—basically logs stacked on top of each other in a circular fashion. Also, tree-ring dating requires trees that put on annual rings, many desert plants do not. The dating method, therefore, wasn’t so useful for the desert Hohokam cultures. Despite the problems, the sheer number of tree-ring or radiocarbon dates in the Southwest is around half a million, giving Southwest archaeologists a very good sense of when things happened.

The Chaco Wood Project has documented every piece of wood at Chaco, some 9,400 pieces. Wood came from a number of sources including:

- Vigas: primary roof support beams

- Latillas: secondary roof support beams

- Door lintels: beams above doorways

Chaco Canyon is mostly treeless with some pinon and juniper on the mesa with a few pockets of stunted Douglas fir, ponderosa pine on the higher mesa elevations to the east. Dean and Warren (1983) estimate that more than 200,000 trees were used to make Chacoan Great Houses. Chacoans likely met this demand by procuring wood from the Chuska Mts. (80 km west) or the Zuni Mts. (80 km south). Most of the wood imported was Ponderosa pine. Stones axes would have been used to cut down trees, but there is a notable lack of axes in the core sites at Chaco. The Chuska Mountains, however, are reported to be “covered” with stone axes, reminiscent of Ranu Raraku being covered in toki! To reduce the weight of beams, they were likely debarked and cured for a year or more before being transported to Chaco. Could the Chacoans really have moved those beams all that way? There are numerous accounts of small groups transporting heavy loads at great distances. Nepali porters (sherpas) carry loads of 220 pounds for 59 miles in 15 days. Not only did they move large beams, but the Chacoans were not satisfied with using rough-cut beams, but put a great deal of time and effort into making the beams aesthetically pleasing by carefully shaping their ends. When I show stone axes to my face-to-face course, some students look at them doubtfully. Could these tools really cut down Ponderosa pines? How long would that take? Experimental archaeology suggests that primary beams (vigas) could have been felled in just 30 minutes. Morris cut down a 10-cm Ponderosa pine in 10 minutes. Delimbing, debarking, and end-finishing, however, likely took seven times as long as felling.

Roads and Astronomy

The Hopewell weren’t the only ones with ceremonial roads. The Chaco road network connects great houses and extends out from Chaco Canyon to outlying areas and Great Houses. These roads, consisting of hundreds of miles of networks, can be seen in aerial photographs (Plog 1997:110). When barriers were encountered, stairs were carved out of the rock so the roads would continue in a straight line. The exact nature of the roads, however, is not known. They may have been used for ritual purposes, for races, or even transport of wood for distant mountains. Surprisingly, the roads don’t appear to have been trading routes. Most of the road segments don’t go very far (.6 miles) and few fall even close to paths that would have minimized travel time between communities. So, they don’t appear important to trade. The roads, however, tend to connect great kivas, very large kivas, and ceremonial sites. In contrast, almost all roads appear to fit more closely with explanations that see the roads as having served localized religious, integrative, or political functions.

Keeping track of time using the moon and sun has been important to people all over the world for thousands of years. Some of the earliest calendars in Sumeria in the Near East were based on cycles of the moon, and only later cycles of the sun. At the Neolithic site of Stonehenge, the famous circle is oriented to the rising sun at the summer solstice. The Maya, as we will discuss later, used a number of different systems for tracking time.

The ancient Chacoans were no different. Rising 135 meters above the canyon floor at Chaco Canyon, Fajada Butte contains a spiral petroglyph, an image pecked into rock, which is partially obscured by stone slabs. The 2-3 meter sandstone slabs, probably naturally oriented, cast shadows of the late morning and midday sun to indicate both solstices and equinoxes. During the summer solstice, for example, a dagger of light bisected the spiral. The feature is therefore been named the Sun Dagger. It has been argued that the Sun Dagger was likely more ceremonial than practical. Ancestral Pueblo farmers, like their hunter-gatherer forebears, knew what they were doing; they knew when to sow and when to harvest based on their own observations. For those who think Chaco Canyon was a pilgrimage center, the Sun Dagger was watched over by priests who sent up the signal by smoke as the dagger approached the central position, announcing the commencement of religious ceremonies and festivals. Some controversy exists over the use and accuracy of this feature. The dagger of light appears near the

central spiral a month before the solstice and then barely moves position. Due to the shifting of the slabs, the site has been closed to tourists.

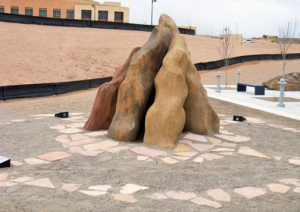

What can we do about these delicate sites being “loved to death” as one past student put it, while still allowing people to connect with the past? One thing that people have tried is 360-tours or virtual tours. No, it’s not the

same as being there, but it allows people to see what the sites are like and enjoy and appreciate them from afar. Another way is to simulate how they functioned. If you go to the New Mexico Museum of Natural History, in

Albuquerque, there is an interactive display that shows you how the Sun Dagger works. Also, near CNM’s Rio Rancho campus, CNM instructor Jaymes Dudding built “Chaco Rising” inspired by the Sun Dagger. What is Chaco? Alternative Views Chaco remains a mysterious place. Even though archaeologists know about particulars—what was in the pot, how much labor was involved, when was it built—there is little consensus about the larger picture about what kind of site it was. One of the reasons is that excavations at Chaco took place before standard excavation techniques were in place. The second reason is that there are very few features in the rooms at the great houses. The third early problem was the comparison with modern-day Pueblo architecture. The rooms at the great houses were assumed to be apartment houses where people lived. Tom Windes, at UNM, estimated the population size at Pueblo Bonito to be no more than 12 families at the most at any one time. He did this by counting hearths. Windes’ study made it clear that the great houses were not apartment buildings where a large population lived. If not houses, what then? Critical Thinking Question: Why did Tom Windes count hearths instead of just counting up rooms?

Today, some archaeologists think Chaco Canyon was a largely empty ceremonial center and pilgrimage site, where just a few priests resided, who would call people in periodically for feasts. In this scenario, the great houses served to integrate people and no one was much more powerful than anyone else. There is some evidence for integrative feasting in the Canyon. This squares well with modern Pueblos who regularly hold integrative feasts and emphasize community over the individual. The rooms could have served as guest quarters, though they are surprisingly bare. Others think Chaco Great Houses were clan houses. Clans are lineages commonly tied to a distant ancestor, frequently an animal. Others, like Stephen Lekson, think that Chaco great houses really were grandiose houses, associated with politically important families. In this scenario, some had far more power and access to wealth than others. The elaborate burials, exotic goods, and crooked staffs suggest power held in the hands of few. The modern-day Pueblo focus on harmony, cooperation, and community was a reaction, he argues, against the corruption of power that occurred at Chaco. Some oral histories also square with this view. The rooms, in this view, would be used for storage of surplus grain (though storage vessels and evidence of spilled grain have not been found). In other areas, people did use masonry structures as storage facilities and lived in wattle and daub structures. Another idea is that the rooms are built for show, in order to support a massive, conspicuous building. Lekson objects to what he called “up-streaming”, or assuming that modern pueblo people were basically just like pueblo people of the past. He argues that not only is this bad archaeology but robs pueblo people of their history.

Perhaps the most interesting take on Chaco Canyon comes from members of Southwest Native American nations. Rina Swentzell of Santa Clara writes: Even then, my response to the canyon was that some sensibility other than my Pueblo ancestors had worked on the Chaco Great Houses. It was clear that the purpose of these great villages was not to restate their oneness with the earth but to show the power and specialness of humans.

Leigh J. Kuwanwisiwma, Director Hopi Cultural Preservation Office associated Chaco great houses with Hopi clans. Chaco is prominent in Hopi oral history. He writes:

The appearance of the supernova of 1054…is today represented by the Blue Star Katsina, who routinely appears in the mixed Katsina dance. According to Hopi oral literature, the “blue star” was the supernatural sign to the Hisatsinom (ancient ones) to end their migrations and begin to converge on certain sites, including Yupköyvi (Chaco).

Dine people (Navajo) have a close relationship with Chaco Canyon. Many Navajos participated in excavations at Chaco in the 1920s (as homesteaders competed for land) and worked to stabilize Chacoan Ruins in the 1930s. Richard Begay of the Navajo Nation related Chaco Canyon to the story of the Gambler. He writes The Gambler “He enslaved the people, and his orders became more severe and exacting.” Lekson suggests that this Gambler story represents “kingship” as embodied at Chaco Canyon.

Connections to the South

In the early 1800s, writers of the Southwest, like Albert Gallatin, thought the Southwest was connected to Mesoamerica via the Toltec, a Mesoamerican culture based on maize agriculture. Others thought it was the homeland of the Aztecs the name of a prominent archaeological site in northern New Mexico “Aztec Ruins”). At the time, the Southwest was a part of Mexico. The Mexico-American War of 1849 separated the Southwest from Mexico and opened it to settlers. with the Great Moundbuilder debate, the idea that modern pueblos were relative newcomers and mere copiers of Aztec culture, was used to justify the displacement of Pueblos from their traditional lands. By the 1900s, archaeologists began to cast doubt on the idea that the now American Southwest was the homeland of the Aztecs and began to see it as a separate entity.

Today, the Mexican influence on the Southwest has become undeniable. For example, One hundred and eleven cylindrical jars were found beneath a room at Pueblo Bonito. Using a technique called liquid chromatography, Patty Crown at the University of New Mexico and her colleague Jeffrey Hurst at Hershey Corporation found evidence that Chaco cylinder vessels were used for drinking liquid chocolate. Cacao trees, which produce the seeds from which chocolate is made, are tropical plant and do not grow anywhere near Chaco Canyon. Chocolate was used as a luxury item for elites only in Mesoamerica, and cylindrical vessels were used for preparing and drinking chocolate among the Classic Maya, which we will discuss in more detail later). Chocolate in some form must have been coming from the south. Exactly where is not yet known.

As we will see in the Mimbres section other exotic goods were coming from the south as well. We today have altered our landscape in numerous ways—mining for fossil fuels, clearing land for domesticated animals to graze, and creating dams for power. Archaeologists and students of archaeology need to be careful not to read what they want to see in the archaeological record—that is, we need to be leery of social and political agendas. Ancient peoples of the Southwest and elsewhere also altered their environment. And we see evidence that people were not necessarily living in ecological harmony with their environment. At Chaco Canyon, packrat middens show that the area was cleared of the native pinon and juniper, and huge amounts of wood were brought in from neighboring areas. In addition, there is evidence of social hierarchy in the burials and exotic goods at Pueblo Bonito. While modern pueblo ideology focuses on harmony and balance, it is possible that this was not always the case in the Southwest.

Leaving Chaco

The Great Houses at Chaco Canyon were abandoned in the mid-1100s, perhaps associated with the drought that hit at the time. The last beam at Pueblo Bonito was cut in 1129 (see dendrochronology below). Some of the outlying communities, like Aztec to the north, continued. But people didn’t entirely disappear from the area. Some people came back into Chaco Canyon after the drought of the mid-1100s. They remodeled the great houses for use as residences—adding hearths, sealing up old doors, creating interior walls, depositing trash and burying dead in old rooms. This is not so unusual—people evidently lived in the Colosseum in Rome in medieval times! Some places in the Southwest flourished after the decline of Chaco, but no single pattern emerged. One site in northern Arizona called Wupatki emerged. Huge quantities of turquoise, shell, copper bells and macaws were discovered there. Wupatki may have been particularly productive farmland due to the cinder cone volcanic eruption at Sunset Crater in 1085 (or so), which covered the soil with beneficial ash. Another site called Aztec in New Mexico may have been the “new Chaco”. Mark Elson is researching the effect of the Sunset Crater eruption and how it might be able to inform us about how humans respond to catastrophes. The ash plume from the volcano would have been visible from Chaco Canyon. This is especially relevant today with catastrophes like hurricanes, earthquakes, tsunamis, and flooding becomes more and more evident. He argues that the cinder cone eruption, which initiates from a crack in the earth with loud cracking and popping coming from the center of the Earth, along with the ensuing lightning, lava flows, ash, and cinders, would have had a significant impact on the surrounding populations—psychologically, religiously, and practically. Impressions of maize in lava were carried away to other areas. Investigators did an archaeological experiment at Hawaii lava flows to see if a detailed impression of maize could be made, and discovered they could not be made very easily. Mark Elson thinks the impressions were made near spatter cones of very hot and fluid lava as part of a ritual, and later carried to a habitation. In areas with thick cinder cones cover, maize agriculture was no longer possible, and people became “volcano refugees”. Experimental archaeology has shown that lighter cinder cover actually serves as a mulch, whereby maize can grow. The volcano refugees subsequently moved to these areas, where maize was previously impossible.

Fracking Chaco?

Chaco Canyon is located in the San Juan Basin, an area rich in fossil fuels. More than 10,000 natural gas wells currently exist. More recently, the Mancos Shale has been eyed for hydraulic fracking for oil. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM), which manages much of the land around Chaco Canyon, has issued more than 200 permits already. Because the original cultural (and environment) assessment was done in 2003 before fracking was possible, environmental, archaeological, and tribal groups have raised concerns. The courts are now considering a moratorium on new oil permits in the area and the decision could also shut down existing fracking operations that have already begun.

Mimbres Mogollon

The descendants of the Mimbres Mogollon were also likely the modern-day Pueblos. Like the Hohokam, the early Mimbres Mogollon lived mainly in pithouses. There is an emphasis on hunting and dry farming with some evidence for irrigation. Around A.D. 900–1000, a fundamental change occurred; the Mimbres Mogollon people shifted to above-ground structures. Cross-culturally, when people live in pit structures they are almost always seasonally mobile. Above-ground structures are associated worldwide with a shift to agriculture and the need for storage of grain.

Mimbres were heavily reliant on maize. The shift to above-ground “pueblos” appears to be associated with increased reliance on maize and increased sedentism. Today, Mimbres architecture is not much to look at, because it was made from large rounded cobbles and fell apart easily, unlike elegant Chacoan architecture. Archaeologist Stephen Lekson called Mimbres architecture “artfully stacked river cobbles.” Because of this deterioration, Mimbres sites seemed less spectacular than sites to the north and were ignored for many years. That is until Mimbres pottery was discovered. In contrast to the great houses at Chaco Canyon, Mimbres house clusters, or room blocks, grew gradually over time as populations increased. Mimbres pottery is the iconic Southwest pottery that inspires Southwest art even to this day. The pottery has a sparkling white background with black mineral paint, and vessels are hemispherical, like half a globe. The images that appear on Mimbres- Black-on-white pottery as it is called include geometric and figurative designs. Women, men, and composite animals can be found on the pots. Females are identifiable by their aprons, which have been found in cave contexts with menstrual blood. Butterfly whorls, a Hopi hairstyle of girls of marriage age, appear on the pots. Men are easily identifiable

by genitalia and often appear on hunting scenes. Throwing sticks, historically used for hunting rabbits are identifiable. Indeed, jackrabbit bones occur in huge numbers on Mimbres sites. Wooden swords and crooked staffs, perhaps symbols of authority, also appear. While some scenes appear to depict everyday activities, others are clearly other-worldly. Marc Thompson, who has lectured in my face-to-face courses, argues that the vessels depict the Hero Twins, who are also prominent in Mesoamerican iconography and origin narratives. The Maya Hero Twins are known for battling monsters in the underworld. Warrior twins also appear in Pueblo and Diné (Navajo) narratives. Images resemble corn maidens and katsinas (kachinas), or ancestral beings, prominent in modern Pueblo religion. Some have suggested that the Mimbres pottery is the first evidence of the katsina in the archaeological record. Also, there are a lot of crescent-shaped rabbits on Mimbres Black-on-white. Many different indigenous tribes of North America believed a rabbit resided in the moon; This rabbit shape can be seen today if you look at the full moon. One depiction shows a crescent-shaped rabbit and kind of starburst, thought to represent the 1054 supernova event in the constellation Taurus, which would have occurred during a crescent moon.

Some Mimbres vessels appear to have been used for domestic, everyday purposes, while others are clearly linked with burials. As at Çatalhöyük, many Mimbres burials were intramural—located inside structures and beneath floors. The face of the deceased often had black-on-white bowls inverted over them. These bowls were ritually “killed” by punching or drilling a hole in the center (remember the Hopewell platform pipes?). The hole has been a metaphor for the sipapu, the conduit or portal between this world and the spirit world. The sipapu is the place of emergence from the underworld and was represented in kivas by a small hole through which the spirits could enter. The vessel itself could have been a metaphor for the dome of a sky. Ruth Bunzel quoted a Zuni consultant: “The sky, solid in substance, rests upon the earth like an inverted bowl”. For the Hopi, upon death, the spirit traveled to the underworld, and upon death in the underworld the spirit returned again to the upper world, creating a cycle (Plog 1997:18). It may be that these killed bowls acted like portals for the return of the soul.

Mimbres bowl thought to represent 1054 Supernova

In the 1970s, prior to laws against unmarked grave excavation, many Mimbres sites were bulldozed by looters looking for spectacular Mimbres pottery which occurred mainly in burials. While sites like the Galaz Ruin were destroyed by heavy machinery. Today, they are completely gone. Who Made the Pots? Most potteries of the Southwest were made by coiling, using long ropes of clay to build up vessel walls. These coils are evident in the finished product. There was no potter’s wheel or pots made from molds. Patricia Gilman looked at the Mimbres pottery to evaluate craft specialization—whether certain individuals or sites were responsible for the manufacture of goods. She found that all of the known Mimbres sites have evidence for production. This finding suggests that Mimbres pottery production was probably not specialized, in the sense that each village was making pottery for themselves and not depending on just one village for these special pots. Steven LeBlanc examined and identified individual potters on Mimbres pottery based on similar styles of depiction. Patty Crown points out that it can take 10 years or more to become a proficient potter and painter, and so there must be some evidence of this learning process in the archaeological record. She identified several poorly executed vessels that were likely painted by children. Because Mimbres Black-on-white vessels were often burial goods and contain potentially religiously charged images, their display in museums and even in digitally accessible databases is controversial. If you go to the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology on the University of New Mexico campus, you will see that some vessels have been removed under consideration of NAGPRA (remember Kennewick Man?). Ancestors continue to be important.

Trade and Exchange

We know that the Hohokam had shells from the Gulf of California and a version of the Mesoamerican ballgame. Chacoans had chocolate ultimately derived from Mesoamerica. Mimbres pottery and material culture make these southern connections even more vivid. Long distances were not a problem for early Southwesterners. Archaeologist Steven LeBlanc suggests the Mimbres acted as middlemen for trade from Mexico to Chaco Canyon.

Mimbres also had Glycymeris shell armlets from the Gulf of Mexico and even depicted these on ceramic vessels. Jett and Moyle (1986) identify 20 fish species, 18 of which are marine fish. They argue that the Mimbres were traveling 1500 miles to the Gulf of California to trade in marine shells and other exotic goods. One image has even been interpreted as a whale, though there is no evidence for aboriginal whaling in that area. Others, like Marc Thompson see fish as representations of souls traveling to the Underworld. Several people have pointed out that the Mimbres fish have odd ventral fins that resemble feet. Interestingly, there is very little evidence that of using fish as a food resource. Note that the fish have four leg-like appendages. Fred Kabotie, a Hopi author and artist, wrote that there is a Hopi story in which children fall into the water and become fish. He suggests the Mimbres might have had a similar story.

Perhaps most spectacular are the macaws and parrots depicted on Mimbres pots. Scarlet macaws have been imported from lowland Mexico, but military macaws and the thick-billed parrots might have been obtained from closer natural ranges in Mexico. Macaws occur about 700 miles away from the Mimbres region in the rainforests of Mexico in La Huasteca, but they may have been found in west Mexico as well (McGuire). Macaw and parrot skeletons, feathers, and artifacts have been found at Mimbres sites and other sites like Chaco throughout the Southwest. Feathers continue to be important ritual objects in the Southwest. Parrots and macaws were important to Mimbres culture and appear to have had ritual significance, and women are shown handling them. This association is interesting because men in Pueblo society traditionally controlled kivas, masks, and altars. The ritual association of women suggests that women may have had significant ritual obligations, particularly with regard to exotic birds, in the past. Significantly, many macaws are able to mimic human voices. It is thought that macaws were brought in as young birds. These birds would have required specialized care in order to survive and flourish during the long journey. Based on skeletal development, year-old macaws were sacrificed in the spring, perhaps during the equinox, and ritually buried. They were likely killed after their long tail feathers grew in. Copper bells from Mexico are found in the Mimbres region and might have been traded along with the parrots and macaws.

Post-Chaco, Post-Mimbres

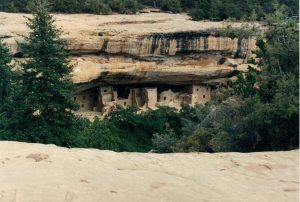

The 1200s saw increased aggregation in apartment-style complexes we now call pueblos. That is, we know people were living in them year-round. The famous Mesa Verde site with its cliff dwellings and large-scale with large populations sites are a good example. This was the beginning of the “Little Ice Age”, a period of widespread cooling.

the growing season brought on by the onset of the Little Ice Age may have pushed people to aggregate and may also be responsible for the violence seen in the archaeological record. Aggregations may have afforded some protection and secured access to land. These aggregations led to close quarters for people, along with their garbage and excrement, which as we have discussed, are not ideal living conditions. In a study of coprolites, ancient feces, from a Mesa Verde community, all samples showed evidence for pinworms.

Compounding the problems of the Little Ice Age, a severe drought referred to as “The Great Drought” struck between ca. 1275 and 1300. This drought precipitated the virtual abandonment of the Mesa Verde region, though people had been migrating out for decades. By 1300, no one was left. In popular literature, we often hear that the Anasazi “disappeared”. We know that they did not disappear but simply moved. Many Pueblo oral histories recount migrations of clans and even tales involving cliff dwellers. Mesa Verdeans in many cases moved south to various areas that were already inhabited, including the Rio Grande Valley. The immigrants met with other people, who sometimes resisted the newcomers violently. In other places, the immigrants brought with them Mesa Verde architecture and artistic styles associated with pottery, and multi-ethnic communities formed. It has been suggested that the newcomers received less profitable land, setting up inequalities between the original residents and the incoming people from the north. Whatever the nature of the cultural contact, most of the petroglyphs (rock art that is pecked or scratched into the rock) at the Petroglyph National Monument here in Albuquerque were created during this time.

At least twelve aggregated villages were in place in the central Rio Grande Valley when Coronado’s Expedition came in the early 1540s in search of gold. A battle between Coronado and the Pueblos may have taken place at a site here in Albuquerque called Piedras Marcadas. Later, the Spanish quest to convert the Pueblos began in earnest, and at sites like Quarai and Gran Quivera south of Albuquerque, indigenous people built churches at the behest of Catholic officials. Pueblo people, of course, still live in the Southwest in 21 different sovereign nations and many still speak their native languages. They maintain traditions that connect them to their ancestral past—kivas, katsinas, and maize farming remain a central part of many Pueblo Indian nations today. We have seen the importance of ancestors in the Neolithic near the east and Ranu Raraku. The same is true in the Southwest, where archaeological sites themselves are sacred ancestral sites. Because of this, archaeological excavation is often seen as a desecration rather than an opportunity to learn about the past. As a result, southwestern

archaeologists are increasingly using non-invasive techniques like surface recording and ground-penetrating radar, and electrical resistivity that show what is beneath the surface of the earth without destroying it in an excavation. Still, excavations do take place when a site is already slated for destruction in the course of building a school, a pipeline, or some other project on state or federal land.

Athabaskans

Early Athabaskan-speaking people in the Southwest, have long been thought to have been relatively late arrivals, coming into the area in the 1500s. These are the ancestors of the Apache and Navajos or Diné. The term Protohistoric is sometimes used to refer to this time between the prehistoric period and the presence of historic documents. That is, there are a few written accounts but widespread historical documents are lacking. Like prehistory, the protohistoric is kind of an odd way to divide up the timeline, but it is still used in a kind of nebulous way. Some scholars think Athabaskans came into the region through a mountain corridor along the border of New Mexico and Arizona, the earliest known dates for Athabaskan sites coming from the mountainous regions. Entry could through the Plains likely occurred as well. The early archaeological record for the early Apaches in the Southwest is scant, but new genetic and artifactual research suggests that small numbers were in the Southwest in the 1400s and perhaps as early as the 1300s, earlier than previously thought. This early Apache presence was in no way uniform throughout the Southwest, exhibiting different forms of adaptations in different environments. Late Apachean (the late 1800s) presence in the Southwest is marked by tipi rings, micaceous pottery (pottery with flecks of mica in it), and projectile points made from metal, especially barrel rings, or glass.

While there are numerous books and conferences dedicated to Chaco Canyon, little has been done to synthesize Athabaskan archaeology. For example, in all of the classic textbooks, Prehistory of the Southwest, by the late Linda Cordell, only four pages are dedicated to Athabaskan and Ute archaeology. Other historically based texts have been written, but none explicitly archaeological in nature. One of the most interesting archaeological applications to understanding Apache history comes from my former employer Karl Laumbach, who writes about a skirmish between the Apache and cavalry unit of buffalo soldiers. By using metal detectors, the field workers were able to identify the rifle and pistol cartridges (metal casing for bullets) of the military men and the Apaches, who used a variety of rifles. The data were entered into a Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Database to develop a visual representation of the skirmish. Not only that, but each weapon leaves a particular mark on the cartridge, which enables researchers to establish that there were more than 180 weapons, and each individual weapon could be tracked across the landscape.

Mexico. (Copyright; Sue Ruth)