3.2: Introduction and Figures

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 34172

Writing as Material Technology

Our shared charge in this volume is to consider writing as material practice. In this way, we endeavor to shift our perspectives on texts from the transparent view that allows us to look past pages, monuments, and objects straight to the content or meaning of recorded signs, and instead to think about the embodied and material nature of writing, and the connection of texts to the material world. These material musings, and the reframing of text to include its physical nature and existence in an experiential world, led me to reflect on how writing may be understood as a material technology. I draw inspiration from Walter Ong (1982) in particular, who frames the emergence of writing in this light. In this way, we can understand text as not only having an effect or impact because of its content (an insult causing a war, an acknowledgment confirming affiliation), but also because of its material form and the ways that form is perceived and used (akin to stone tools changing the possibilities for cutting or processing, the wheel impacting experiences of distance and connection). Textual objects — a phrase I use to keep in the forefront of our minds the simultaneously material and textual nature of the artifacts I discuss — accomplish certain types of work that draw upon both the content and the material nature of the text. By considering texts in an artifactual light, I argue that texts do important work in organizing the material world. Furthermore, the specific material forms that texts take impact the ways in which such work is carried out.

I explore these ideas in the context of Classic Maya writing. For the Maya text objects I examine — a stone monument, a painted ceramic vessel, and a set of incised bone needles, all adorned with Maya hieroglyphic writing — I suggest that an orientational technology is at work. That is, the perception and use of these text objects serve to locate people in culturally defined landscapes, and in particular, within socio-political landscapes that include both experiential and imagined aspects. The experience of these texts allowed ancient viewers to situate themselves along a series of axes, not all of which are obvious or visible through other modes of material analysis. Particularly important are the juxtaposed perspectives of the immediately accessible aspects of a polity (spatial, temporal and political), and the more abstract ideas of what lay beyond.

As an orientational technology, these text objects are quite different from modern technologies that serve to give us our bearings upon visiting a Maya archaeological site: a topographic map, a compass, a GPS unit, and, of course, a wristwatch. And yet, in both modern and ancient instances, orientational technologies involve accessing content that shapes human actions in the world, and that is experienced in specific ways representative of particular, shared worldviews. As we read a site name or elevation on a worn and floppy paper map, or time from numerals on a metal object that we wear, we participate — consciously or not — in shared understandings of relative positioning in the universe. The text objects that I examine encode perspectives that located Maya individuals in relative positions through expressions of the shape and nature of the realms in which they lived, including dimensions of territoriality, conceptions of temporality, and constructions of personal and institutional difference.

A Few Thoughts on Technology and Landscapes

I mentioned above that Ong’s work (1982) provided inspiration for considering writing as a type of technology. For him, technology is marked, at least in part, through “the use of tools and other equipment” (Ong 1982: 80–81). This is a fairly limited definition, though he notes that the transformational power of technology is not only as an “exterior aide”, but also as yielding “interior transformations of consciousness” (Ong 1982: 81). Following in the footsteps of Ingold (2000: 294–299), I extend Ong’s premise and embed those tools within active processes and particular types of knowledge, emphasizing both the material extensions of human selves that carry out work (in this case, both the tools that create texts, and subsequently the texts themselves) and the cultural knowledge necessary for these technologies to be created and put into action. For the purposes of this chaper, I do not introduce the concept of technology as an opposition to art, a dichotomy that implies a division between execution and conception (Ingold 2000: 295), and which may not accurately describe relationships between rulers and artisans, often conceived as attached specialists in Maya contexts (Inomata 2001). Rather, by using the term ‘technology’, I shift our interpretation of Maya text objects from an aesthetic interpretation or historical reading, to an appreciation of the constructive cultural work being carried out through textual implements.

As I explore the idea that Maya text objects may be considered as a type of efficacious technology serving to orient viewers and readers, I refer to the idea of landscape. I describe in this chapter a variety of culturally constructed landscapes (spatial, temporal, political, and gendered). While the natural landscape and environment are critical elements to examine in understanding ancient societies, the work that the text objects I consider are doing is focused on mediated and experiential surroundings: how people would have perceived their place in the world, on multiple planes, based on both actual experience and imagined extension. As human constructs, the landscapes I consider are unstable and constantly transformed, and require maintenance in order to retain their contours, or to change in response to shifting circumstances. I argue that text objects provide a particularly powerful communicative avenue for carrying out this work.

A Brief Background on the Maya

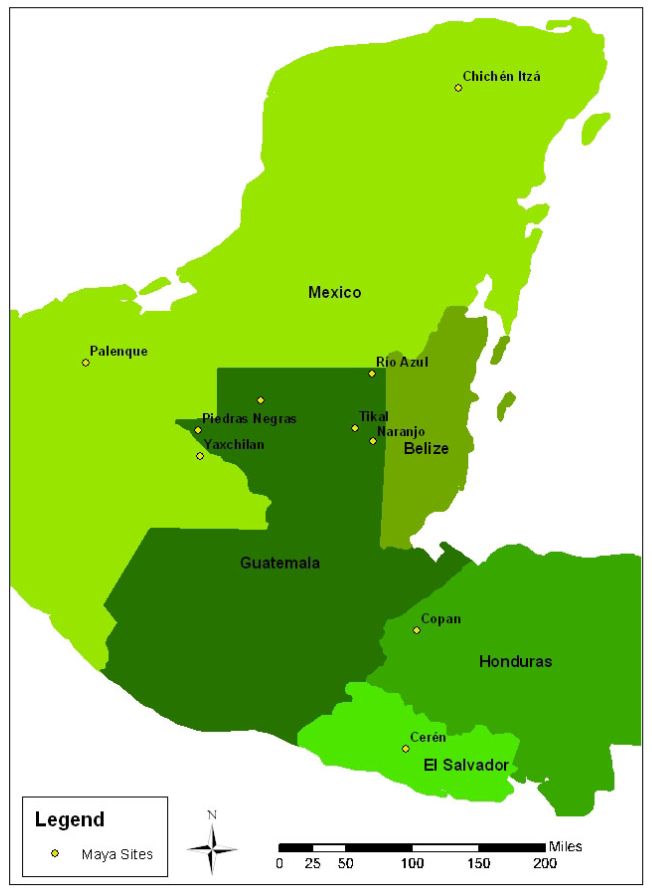

Before exploring these ideas through three case studies, I first provide some background for those less familiar with Maya contexts. The texts I discuss in the following examples were created by Maya scribes in Central America (Figure 1) during the Classic period (c.ad 250–850). The world of the Classic Maya was characterized by a fragmented political landscape of independent city-states each ruled by a k’uhul ajaw (holy lord), whose authority was based on both political and religious stature. The Classic-era apogee of Maya culture was a period of trade, social and political interaction between sites, ongoing development of the governing apparatus, as well as conflict between competing polities.

The sophistication of the Maya world is marked in part by their elaborate writing system, one that allows us to learn the names of some of that era’s key players, and to establish a tightly controlled chronology for the histories of these polities. Some of the extant texts that epigraphers examine today are carved on stone monuments, both upright stelae that were exhibited in public places, as well as architectural elements such as panels, lintels, and benches that would have been located in more restricted spaces. Additionally, hieroglyphic texts are found on portable objects such as painted ceramic vessels, as well as personal items such as carved bone and shell objects. The challenges of preservation in a tropical environment mean that more perishable substances that likely were vehicles for writing, such as bark paper, rarely survive.

The complex logosyllabic script of the Maya constituted a limited resource — legible to a restricted segment of the population, and written primarily by trained scribes, many of whom were also members of the royal court. In Maya contexts, however, literacy should not be seen as a binary issue (Houston and Stuart 1992). The frequent juxtaposition of text and image led to an interpretive interplay between the written word and expressive depictions. In the examples that follow, the texts and images on Maya artifacts interact with the material nature of the objects to become powerful communicative devices, accomplishing work by conveying meaning, but also through orienting and situating those who interacted with these text objects in both literal and metaphorical landscapes.

Figure 1: Map of the Maya area, including sites mentioned in the chapter. Map by Dayna Reale. Reproduced with permission.

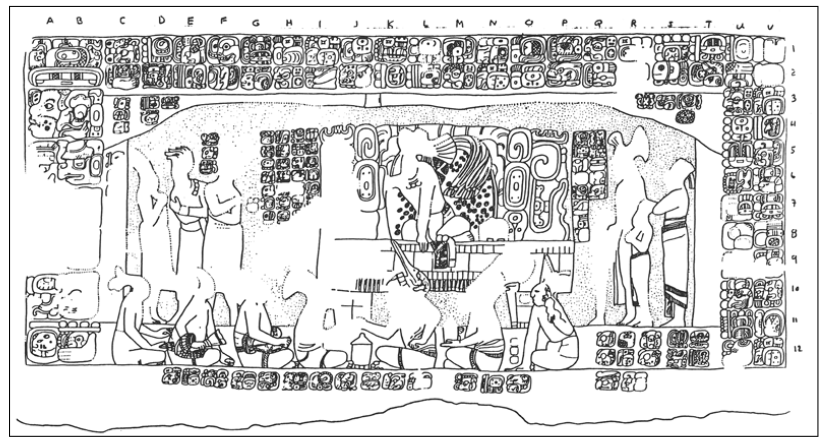

Figure 2: Piedras Negras Panel 3. Photograph by Megan O’Neil, courtesy of Megan O’Neil and the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología de Guatemala, and the Minesterio de Cultura y Deportes, Dirección General de Patrimonio Cultural y Natural.

Figure 3: Drawing of Piedras Negras Panel 3 (from Schele and Friedel 1990: 304). Drawing by Linda Schele, © David Schele, courtesy Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc., www.famsi.org.

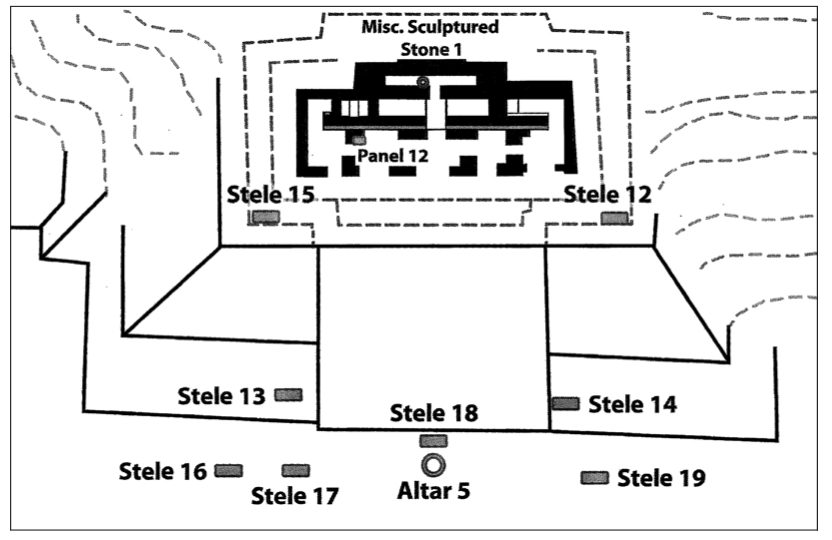

Figure 4: Plan of Piedras Negras Structure O-13, with known monument locations marked; precise original location of Panel 3 is unknown (from O’Neil 2012: 141). Image by Megan O’Neil and Kevin Cain (INSIGHT). Reproduced with permission.

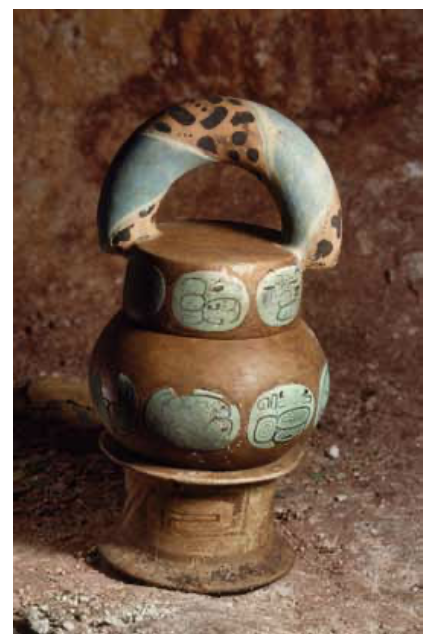

Figure 5: Río Azul Vessel 15. Photograph by George F. Mobley/National Geographic Creative. Reproduced with permission, and with the generous support of the Charles Phelps Taft Research Center, University of Cincinnati.

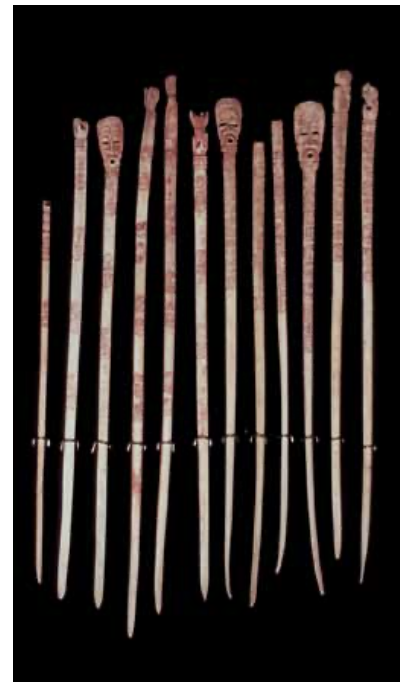

Figure 6: Naranjo weaving bones. Photograph by Chelsea Dacus. Reproduced with permission.

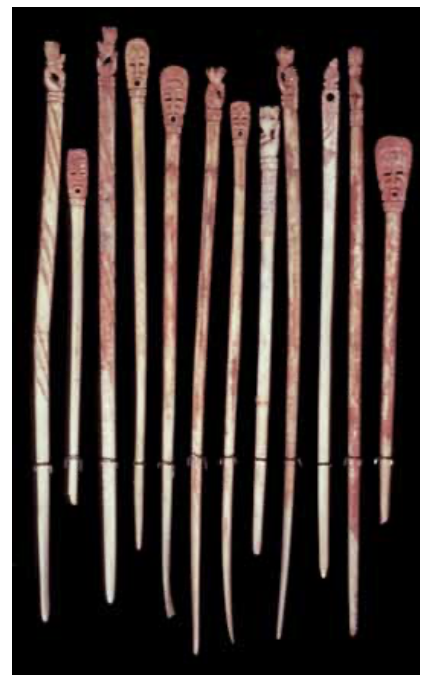

Figure 7: Naranjo weaving bones, continued. Photograph by Chelsea Dacus. Reproduced with permission.

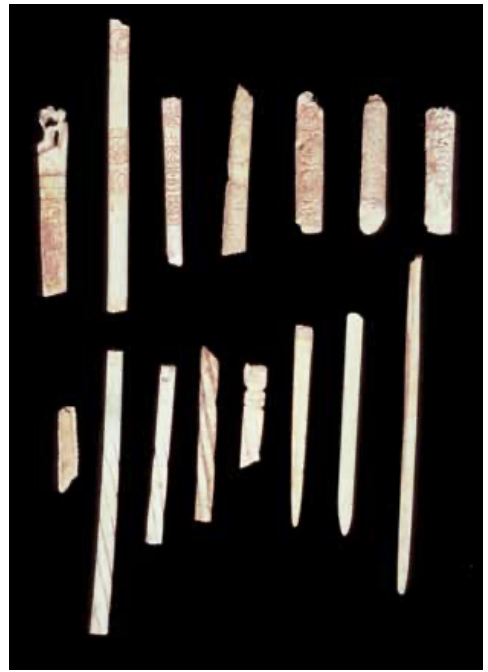

Figure 8: Naranjo weaving bone fragments. Photograph by Chelsea Dacus. Reproduced with permission.