Writing helps to objectify ideas and to mediate symbols by expressing and transmitting information and meaning through its visual form, which is also constituted by its materiality. Recent cross-disciplinary studies have demonstrated that considering writing not from a purely epigraphical stance but as material practice can transform research agendas by bridging archaeology, social anthropology and cognitive semiotics. A material practice approach specifically allows us to understand the following crucial questions: how the physical substance of the writ- ing surface helps the inscribed objects transcend space and time (Zinna 2011: 635); also, how writing technologies embody our mental trajectories by shaping writing processes (Haas 1996). These technologies carry with them an embedded history of design, which tends to become more complex with each subsequent stage of development (Schmandt-Besserat 2007). Such a discourse is novel in Minoan epigraphy, which is either concerned mainly with attempts at script decipherment or is integrated into socioeconomic studies with a focus on administrative dynamics. In these narratives, the significance of visual display as well as other types of embodied perception of Minoan writing is usually overlooked. This chapter accordingly seeks to outline a framework for exploring modes of display and the perception of the two earliest Aegean scripts that were used on 2nd–millennium bc Crete. Since Cretan Hieroglyphic and Linear A are still undeciphered, their attestations will be studied as signs in the Peircean sense, “namely something which stands to somebody for something in some respect or capacity” (Peirce 1931: 2.228). Attention will be redirected from the written form of the relevant inscriptions, the signifier or representamen (Chandler 2007: 30), to the physical aspects of their material supports and to the symbolic messages projected by them. The premise underlying such a pursuit is that material, size, shape and other functional aspects of the inscribed artefacts were also perceived by past actors as signifiers; these were employed and transmitted within various material and ideological contexts. For example, formal Egyptian hieroglyphic appearing on monuments may have implied a formal type of communication with the divine sphere, as opposed to the cursive hieratic version of the script (Wilson 2003: 22–23, 49–57).

In addressing the symbolic resources embodied by Minoan inscribed artefacts, I shall follow the notion that objects not only became invested with meaning through their association with people but also were themselves constitutive of meanings, behaviour and social relations (Dant 2005: 60–83; Gell 1998; Graves-Brown 2000; Knappett 2005). Meaning is formed from the individualised multi-sensorial experience of the objects and from discourse that includes performance, such as public display events, funerary ceremonies and periodically enacted rituals (Jones 2007: 42). Hence our examination of categories of artefact that bear Cretan Hieroglyphic and Linear A inscriptions will examine the symbolic connotations of these two scripts with particular attention directed the impact of the materiality of their supports on perception. Special emphasis will be given to emblematic artefacts, such as hieroglyphic sealstones — sphragistic devices inscribed with hieroglyphic signs. Moreover, the combination of script with images that may have constituted a visual code on these and on earlier seals will be discussed. In addition to hieroglyphic sealstones, metal, stone and clay objects carrying Linear A inscriptions of a non-administrative character will be considered. Semiotic relationships that are grounded in the material properties and the performative capacities of the objects themselves will also be explored, in order to detect aspects of artefactual meaning that may not be immediately obvious from a conventional perspective.

To this end, the following questions will be posed: how did the shape and size of the Cretan Hieroglyphic and Linear A inscription-carriers inform the creation of the relevant objects? Did the materials of the writing supports make possible different recording formats? Which physical and compositional parameters were pertinent to the experience of the inscriptions thereon by viewers, including elites, or by other segments of the population? In order to address the modes of perception of Minoan writing, the discussion will rely on integrational semiology, an approach that treats reading and writing as integrated and linked by “reciprocal presupposition” (Harris 1995: 6). From this perspective, the graphic symbols of the scripts are arranged in the “graphic space”, namely the area where text is positioned and read (Harris 1995: 121), according to a visual logic that guides perception. This logic involves conventions whose structure can be understood as a “graphic rhetoric” (Drucker and McGann 2001: 96–98). In order to reconstruct the latter with regard to Minoan writing, I will treat directionality, alignment and scale of the Hieroglyphic and Linear A signs as indexes, and consider the ways in which these may have affected the experience of the inscribed artefacts by social actors, as well as the role of these objects in practices of remembrance.

| Pottery Phase |

Cultural Phase |

Dates (B.C.) |

| Early Minoan (EM) I-III |

Early Prepalatial |

c.3100 / 3000-2100 / 2000 |

| Middle Minoan (MM) IA |

Late Prepalatial |

2100 / 2000-1925 / 1900 |

| Middle Minoan (MM) IB-II |

Protopalatial |

1925 / 1900-1750 / 1720 |

| Middle Minoan (MM) III - Late Minoan (LM) IA-B |

Neopalatial |

1750 / 1720-1490 / 1470 |

Table 1: Chronological table.

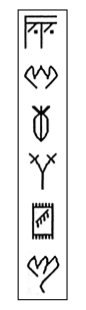

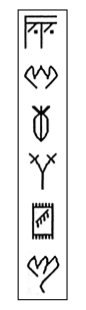

Figure 1: Examples of Cretan Hieroglyphic logograms (after Olivier and Godart 1996: 17).

Figure 2: Four-sided steatite prism (Olivier and Godart 1996: #288), HM S-K2184 from Malia with horizontally aligned signs. a) side α; b) side β; c) side γ with seal motifs; d) side δ. Length: 1.54 cm.

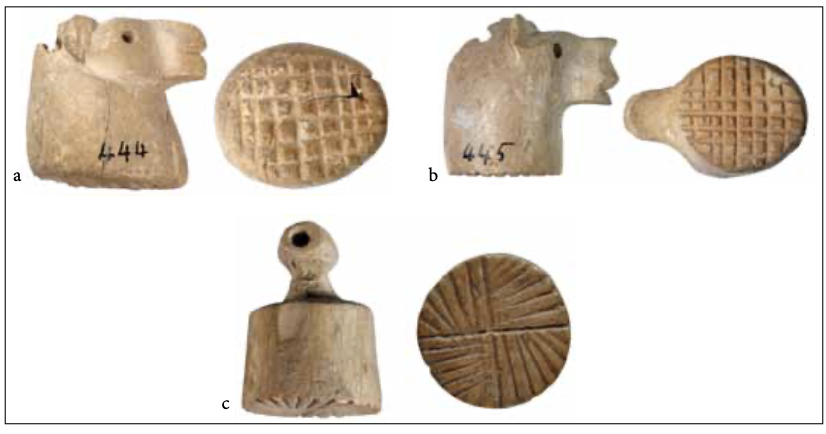

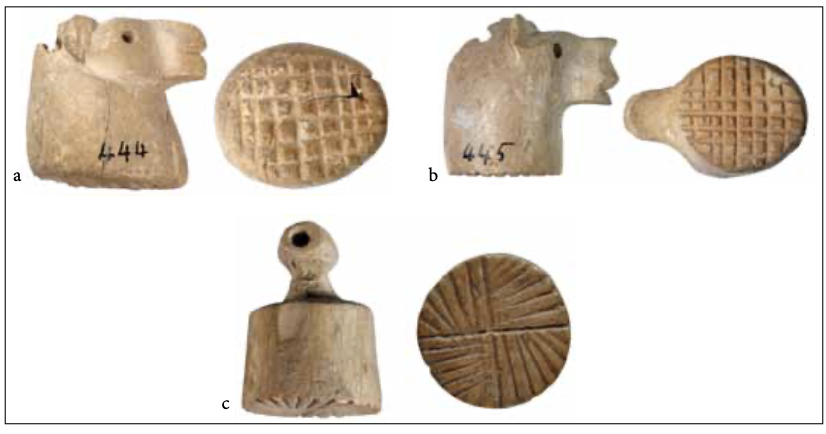

Figure 3: Early Minoan II bone seals from the Ayia Triada tholos Α with linear motifs. a) Height: 2.0 cm. CMS II.1, no. 17 / HM S-K444; b) Height: 1.8 cm. CMS II.1, no. 18 / HM S-K445; c) Height: 1.8 cm. CMS II.1, no. 24 / HM S-K452.

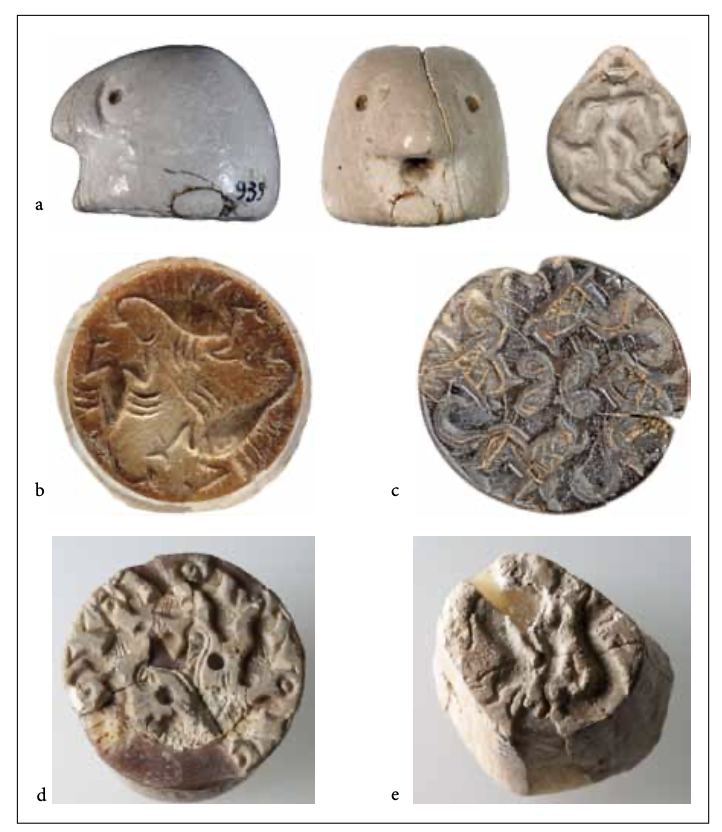

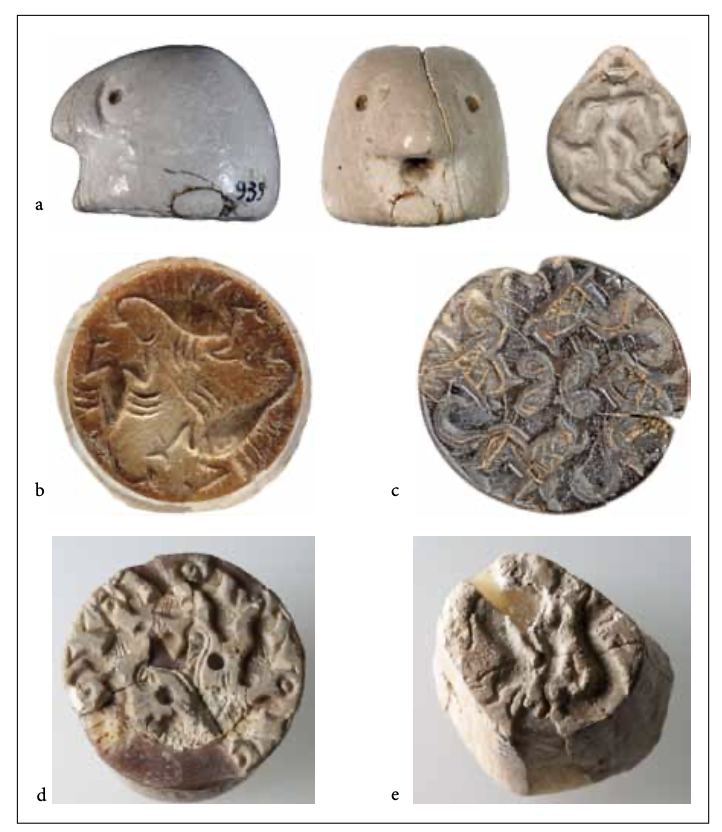

Figure 4: Early Minoan III–Middle Minoan IA hippopotamus ivory seals. a) Length: 2.3 cm. CMS II.1, no. 469 / HM S-K939 from Sphoungaras; b) Length: 3.5 cm; Width 3.5 cm; Thickness 3.2 cm. CMS II.1, no. 248 / HM S-K1039 from Platanos tholos A; c) Length: 1.97 cm; Width 1.9 cm; Thickness 2.97 cm. CMS II.1, no. 3 / HM S-K680 from Drakones tholos tomb D; d) Length: 3.33 cm; Width 3.32 cm; Thickness 2.97 cm. CMS II.1, no. 312a / HM S-K1104 from Platanos tholos Β; e) Length 2.5 cm: Width 2.18 cm. CMS II.1, no. 442b / HM S-K1578 from the Trapeza cave.

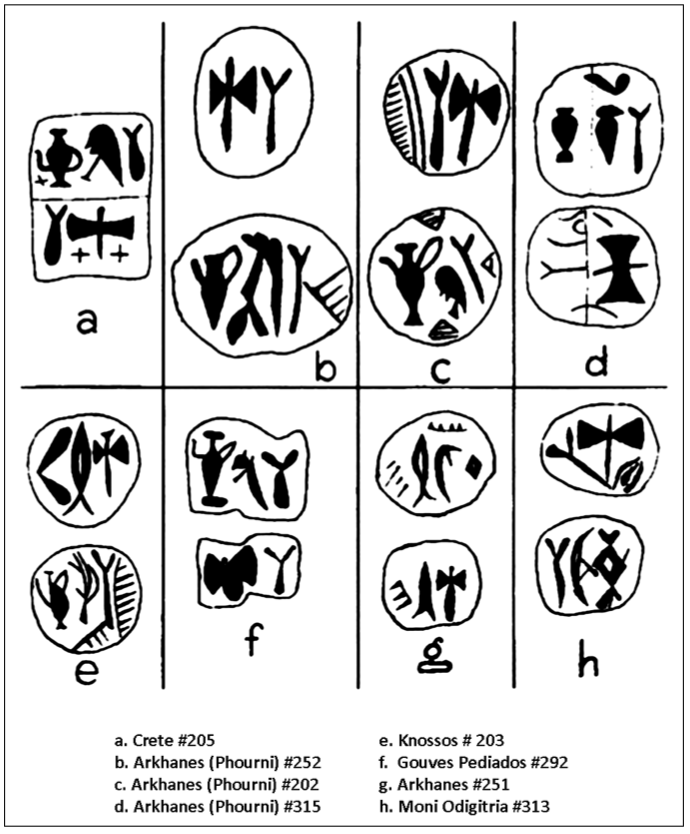

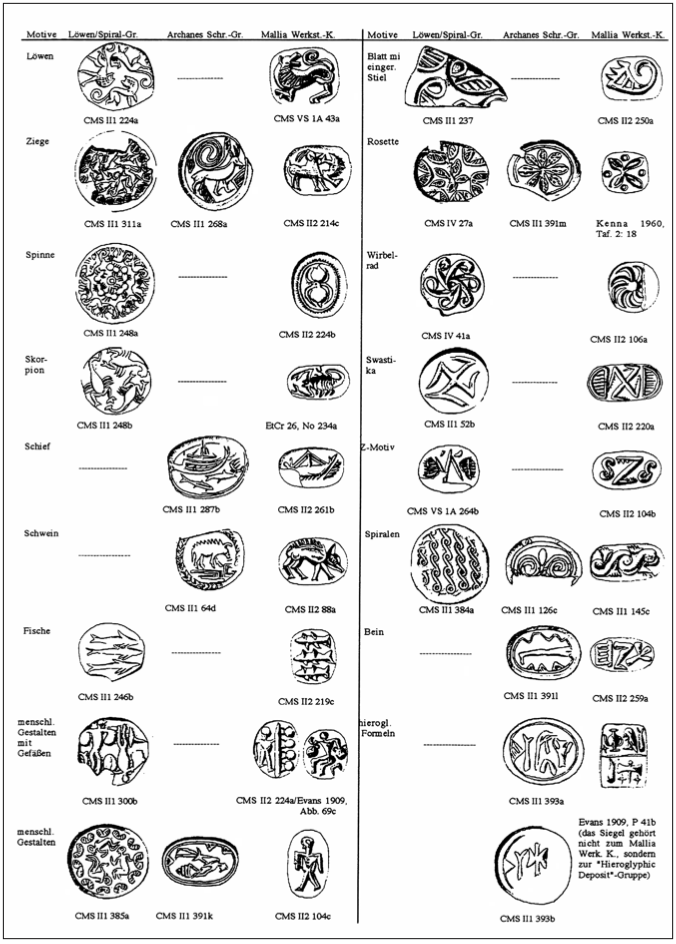

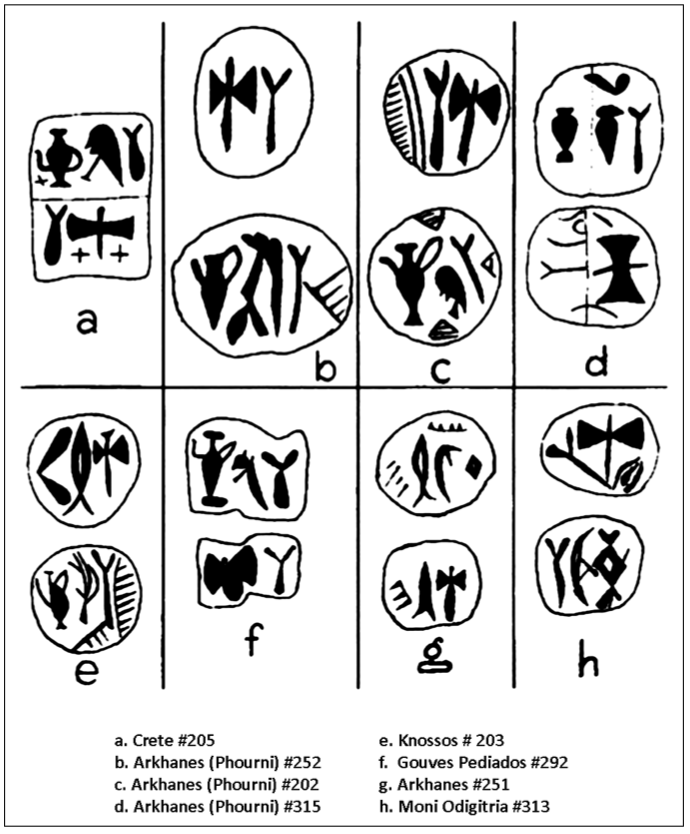

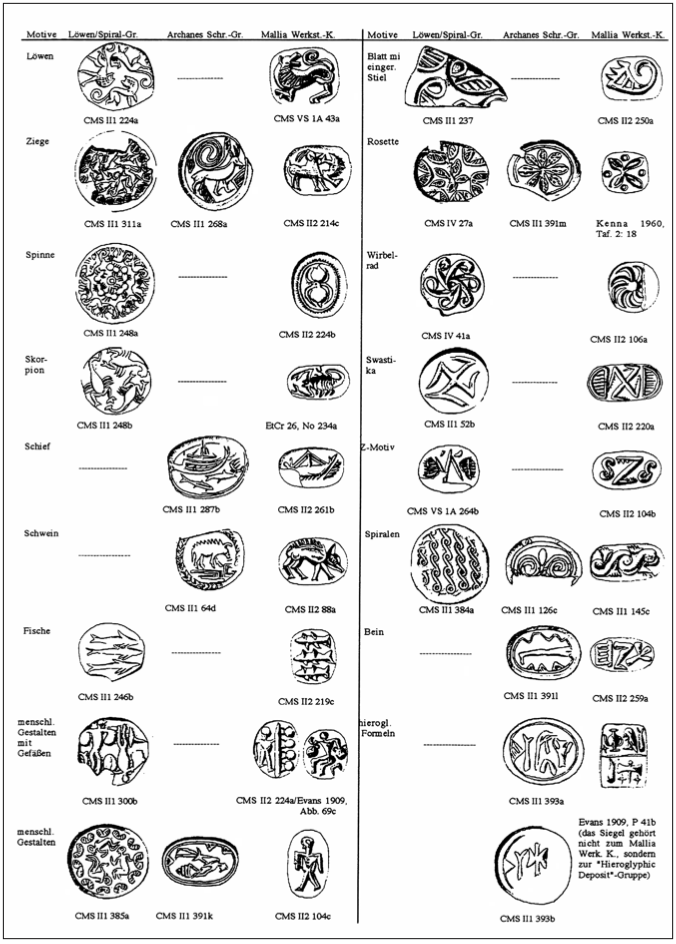

Figure 5: ‘Pictographic’ signs on the ‘Archanes Script Group’ seals and on later Hieroglyphic seals (after Sbonias 1995: table 3).

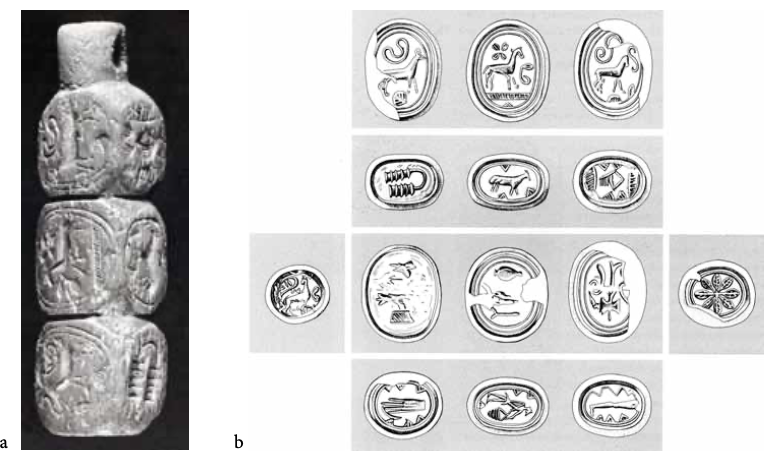

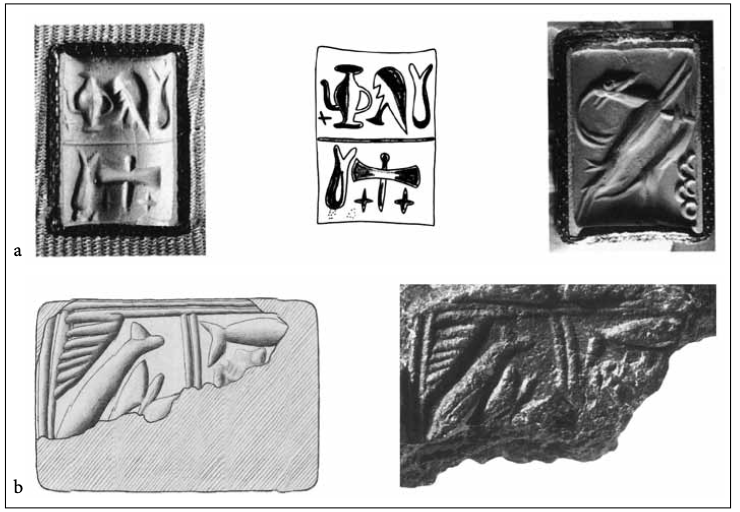

Figure 6: Seals that bear the ‘Archanes formula’ (after Brice 1997: 94, fig. 1).

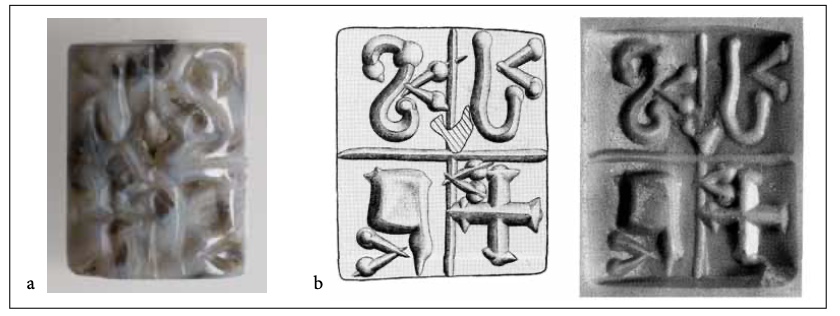

Figure 7: Seal, CMS II.1, no. 126 / ΗΜ S-K817 from Kalathiana tholos K. Length: 1.9 cm; Width 1.9 cm; Thickness 1.9 cm.

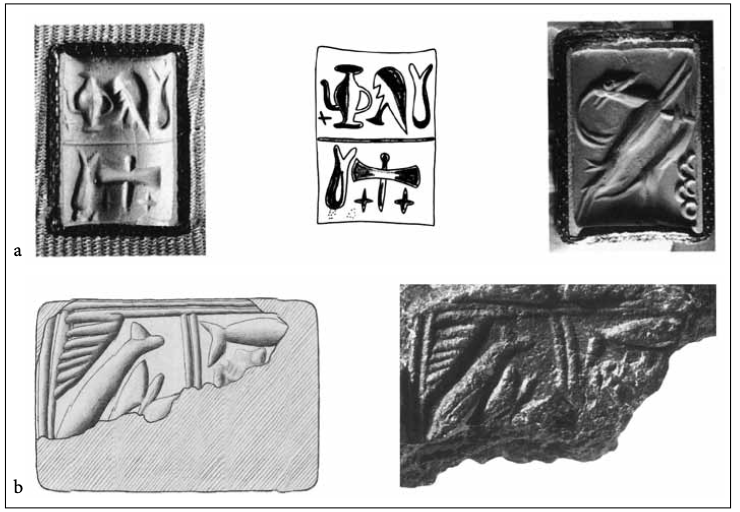

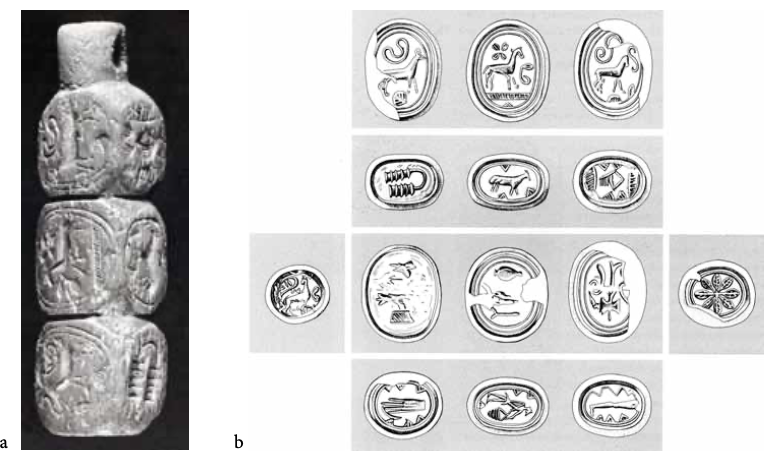

Figure 8: a–b) Archanes bone seal with the ‘Archanes formula’. Length: 5.67 cm; Height: 1.28 cm. CMS II.1, no. 391 / HM S-K2260 (drawing after Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki 1997: fig. 284).

Figure 9: a) ‘Egyptianising’ stone amulet from Knossos. Height: c.1.5 cm. HM S-K631; b) Zoomorphic seal of hippopotamus tusk from Platanos tholos tomb A. Length: 2.5 cm; Width: 2.2 cm; Thickness: 3.5 cm. CMS II.1, no. 249 / HM S-K1040; c) Prepalatial bone amulet. Length: 3.0 cm. HM O-E122; d) Prepalatial stone amulet. Length: 2.0 cm. S-K1252.

Figure 10: a) Agate stamp seal. CMS VII, no. 35 (Olivier and Godart 1996: #205); b) Knossian sealing. Length: 1.4 cm; Width 0.7 cm. CMS II.8, no. 29 / HM S-T372.

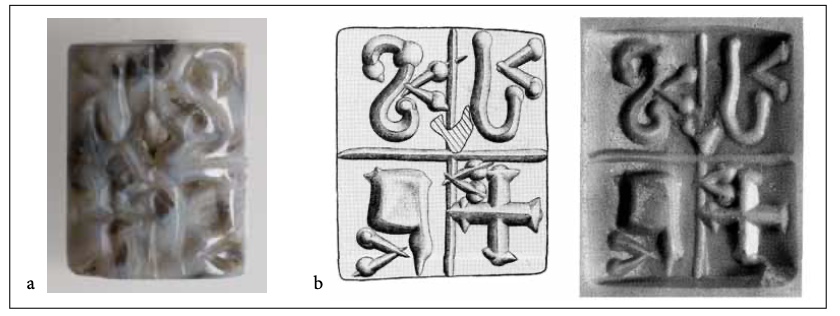

Figure 11: a) Flattened cylinder of agate, CMS III.1, no. 149 (Olivier and Godart 1996: #206); b) Drawing and cast.

Figure 12: Steatite petschaft seal, CMS III.1, no. 103 (Olivier and Godart 1996: #180). a) Seal face; b) Profile.

Figure 13: Quartier Mu steatite signet (Olivier and Godart 1996: #197). Length: 1.35 cm; Width 0.8 cm. HM S-K2390.

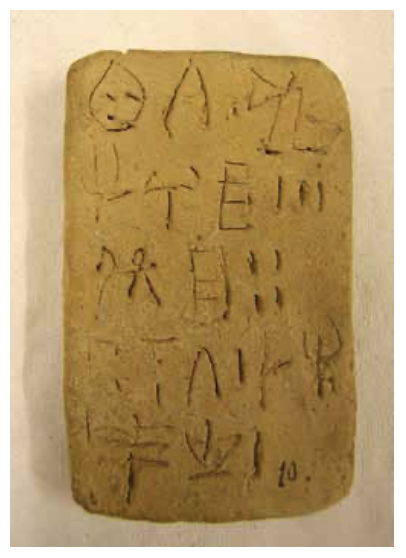

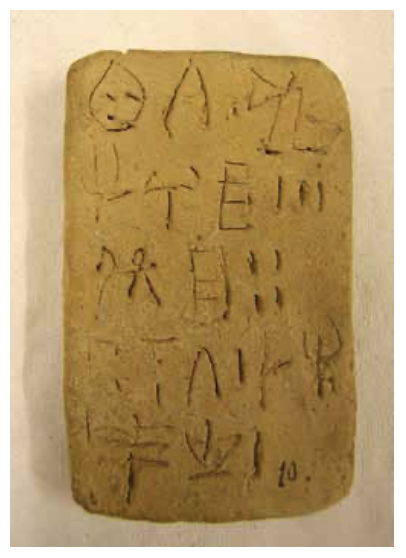

Figure 14: Linear A clay tablet. Height: 1.8 cm. HT 7 / HM P-N10.

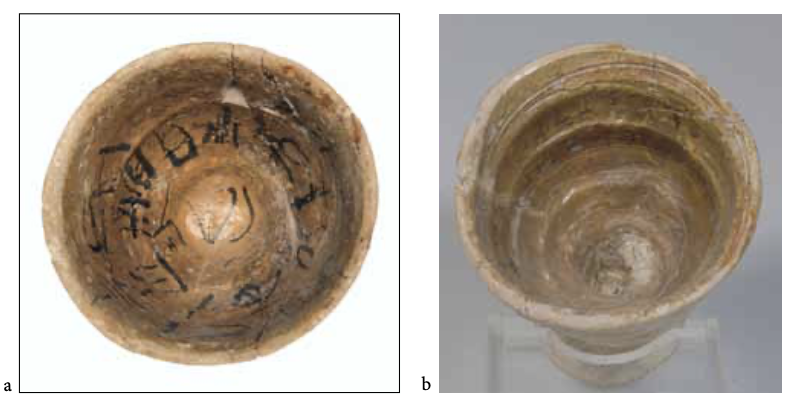

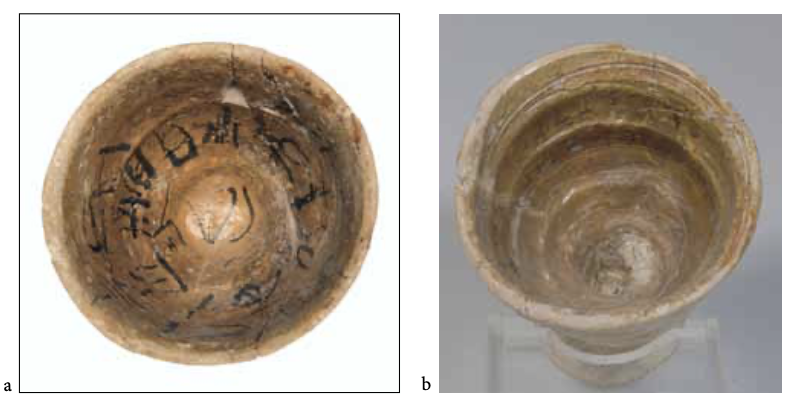

Figures 15: a) Ceramic conical cup. Diameter of rim: 8.4 cm. KN Zc 6 / HM P2630; b) Ceramic conical cup. Diameter of rim: 9.2 cm. KN Zc 7 / HM P2629.

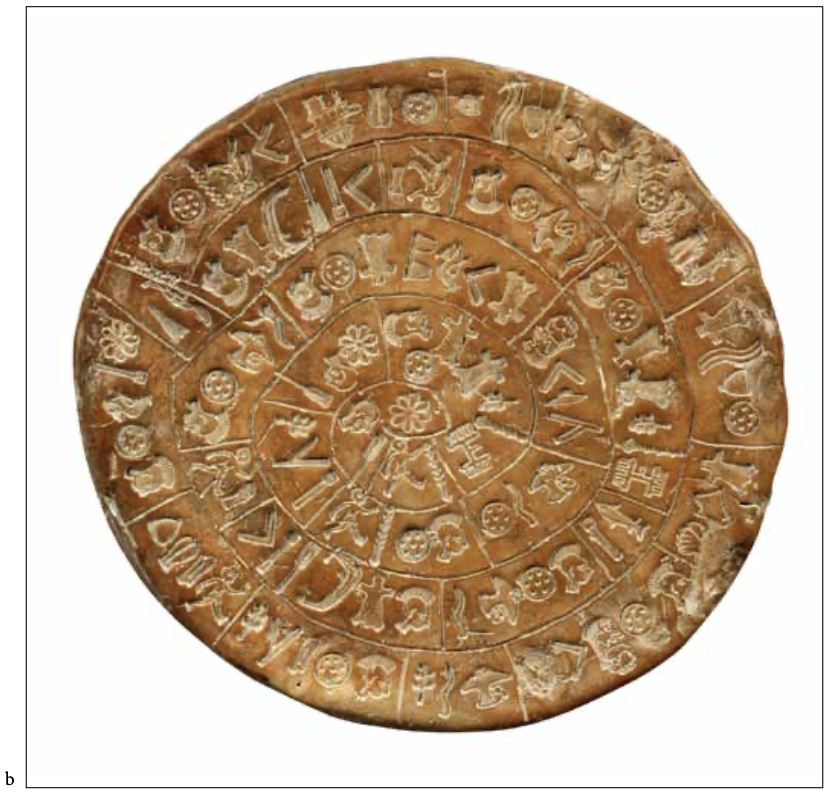

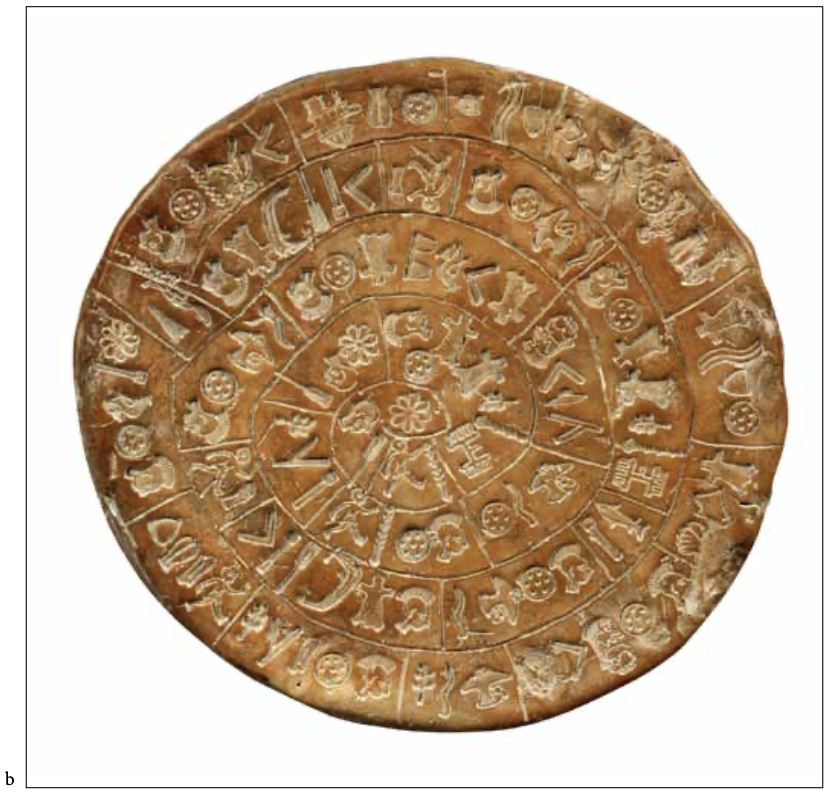

Figure 16: a) Mavrospelio ring made of gold. Diameter: 1.0 cm × 0.85 cm. KN Zf 13 / HM Χ-Α530; b) Phaistos disc with stamped inscription, made of clay. Diameter: 15.8 × 16.5 cm.

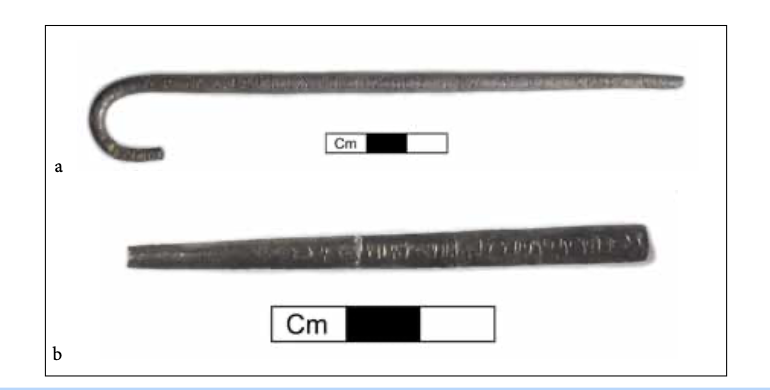

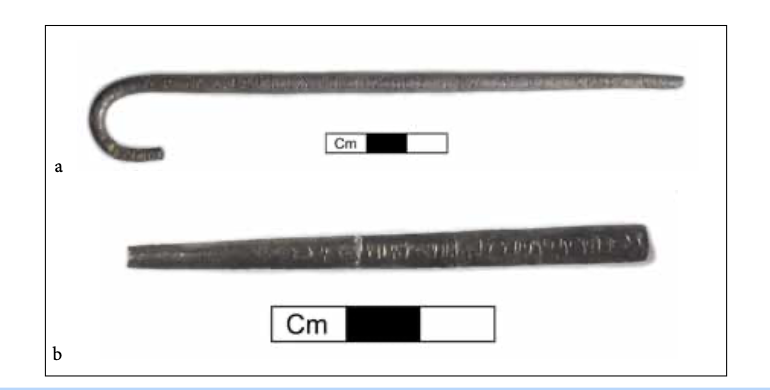

Figure 17: a) Silver pin. Length: 15 cm. KN Z 31 / HM Χ-A540; b) Silver pin. Length: 7 cm. PL Zf 1 / HM Χ-Α498.

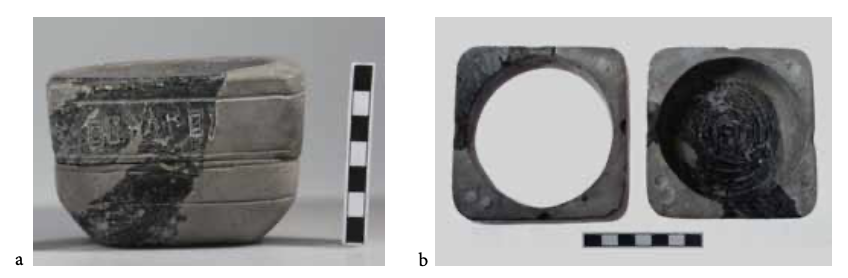

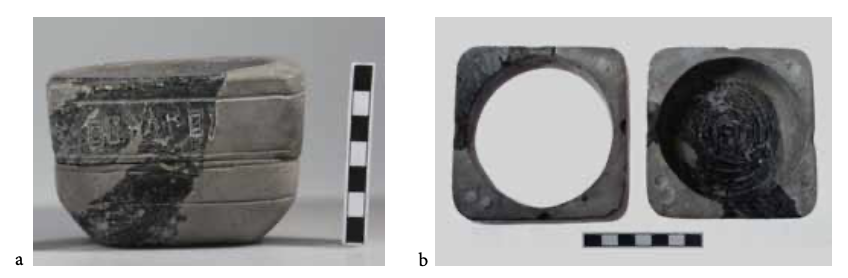

Figure 18: a) Stone libation table from Apodoulou with its two parts joined. Height: 6.5 cm. AP Za 1 / HM L2478; b) The two parts of the libation table separated.

Figure 19: Stone libation table from Palaikastro. Height: 18.3 cm. PK Za 11 / HM L1341.

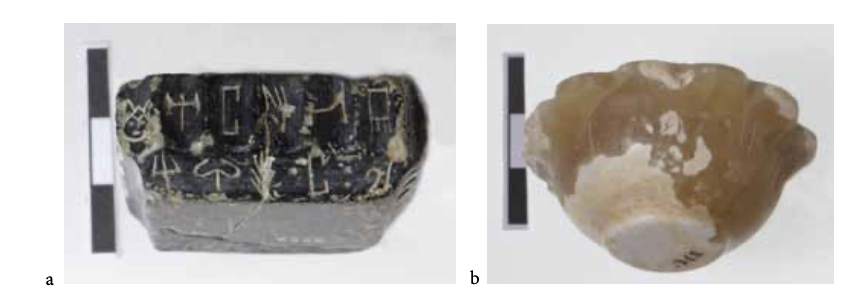

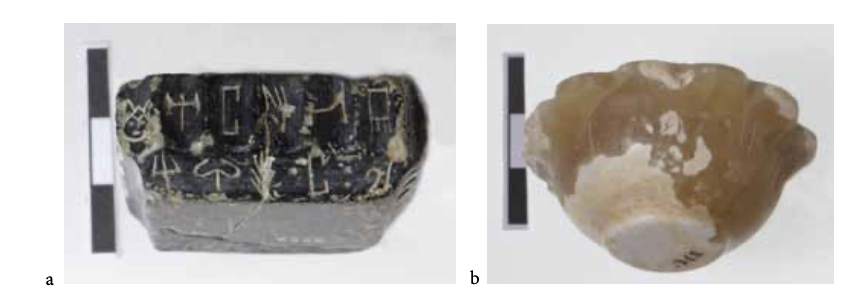

Figure 20: a) Stone libation table. Height: 1.9 cm: Width 4.3 cm. IO Za 2 / HM L3557 from Ioukhtas; b) Stone cup. Diameter 4.2 cm: Height: 2.5 cm. IO Za 6 / HM L3785 from Ioukhtas.

Figure 21: a) Alabaster ladle. Length: 6.5 cm. TL Za 1 / HM L1545 from Troullos; b) Stone ladle. Length: 10.3 cm. HM L2101 from the House of the Frescoes at Knossos.