Let me read the tablets in the presence of the king, my lord, and let me put down on them whatever is agreeable to the king; whatever is not acceptable to the king, I shall remove from them. The tablets I am speaking about are worth preserving until far-off days. (7th century bc cuneiform inscription on clay tablet from Nineveh, capital of the Neo- Assyrian empire, see Frame and George 2005: 278).

In an age where ‘the death of the book’ is heralded almost daily (Ehrenreich 2011 poetically situates the debates), and where new modes of expression and consumption of the written word are freely elaborated, we are perhaps especially sensitised to the materiality of the writings, and the readings, that inhabit our world. In this chapter, following a brief review of current research, I consider some key questions in the materiality of writing, drawing on case-studies from the world of “cuneiform culture” that dominated the ancient Near East for more than 3000 years from its beginnings around 3200 bc (Radner and Robson 2011).

Following a long and occasionally fraught relationship between archaeologists and historians of the ancient Near East (Liverani 1999; Matthews 2003; Zimansky 2005), the topic of textual materiality is increasingly considered in studies by Near Eastern epigraphists and archaeologists working together to achieve shared aims. It has long been appreciated that the shape and format of clay tablets bearing cuneiform script is frequently related to the content of those texts (e.g. Radner 1995) but such associations, and many others, are now being explored in more rigorous detail and with new scientific methods.

In his recent book, Dominique Charpin (2010: 25–42) has articulated a manifesto for what he terms a “diplomatics of Mesopotamian documents”, whereby attention of the historian expands beyond the purely textual content of cuneiform documents to a concern with physical form, including materiality (of tablet and stylus), the palaeography of written signs, the layout of texts, and the use of seals on texts (see also van de Mieroop 1999). In the broader context, the historian must also consider issues of how specific texts, or groups of texts, came to be written in the first place and how they came to be preserved within archives, or otherwise, for ultimate discovery in the archaeological record. A model of fruitful collaboration between epigraphy and archaeology is the study by Italian scholars of Ur III texts (late 3rd millennium BC) from southern Iraq currently housed in the British Museum (D’Agostino et al. 2004). Their study combines conventional epigraphy with analytical approaches to a range of material attributes including formal typology of tablet shape and size, location and type of fingerprints, and the varying uses of seals on texts. Most innovative is their application of archaeometric methods (Inductively Coupled Plasma — Optical Emission Spectroscopy and Inductively Coupled Plasma — Mass Spectrometry) in order to characterise the clays employed in tablet manufacture. While so far limited in its interpretive scope, their pilot study starts to map out the contours of a future landscape of investigation, offering approaches and methods which may have applicability across and beyond the world of cuneiform culture.

Two larger-scale developments encourage the belief that holistic, integrated approaches to the materiality of texts from the ancient Near East, and beyond, are becoming established in the academic arena, as advocated throughout the 2009 Writing as Material Practice conference (see Piquette and Whitehouse, this volume). Firstly, in April 2010 at the 7th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East (7ICAANE) in London a one-day workshop, organised by Jon Taylor of the British Museum, was devoted to the topic of ‘Composition and Manufacture of Clay Tablets’. Papers covered a range of material topics including plant and shell inclusions within clay tablets as potential indicators of provenance and local environment, the recycling of tablets, the possible detection of increasing salinity in the Mesopotamian environment through analysis of diatoms, phytoliths and shells contained within clay tablets, and applications of portable X-Ray Fluorescence (pXRF) to clay tablets. Subsequent publications by Taylor and colleagues confirm the strong trajectory of this area of research (Cartwright and Taylor 2011; Taylor 2011). Secondly, at Heidelberg University a generously-funded Collaborative Research Centre has been established by the German Research Foundation in order to investigate ‘Material Text Cultures: Materiality and presence of the scriptural in non-typographic societies’, with the commendable ambition to apply a range of scientific and humanities approaches to the study of textual materiality from many societies of the ancient world, including Egypt and Mesopotamia. Here, indeed, a new ‘textual anthropology’ is taking shape (for information on the new centre see: www. materiale-textkulturen.de).

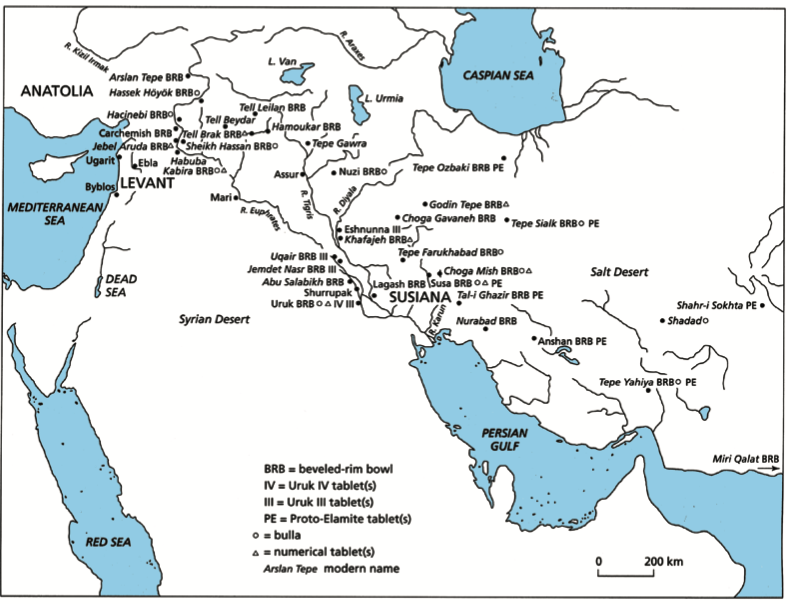

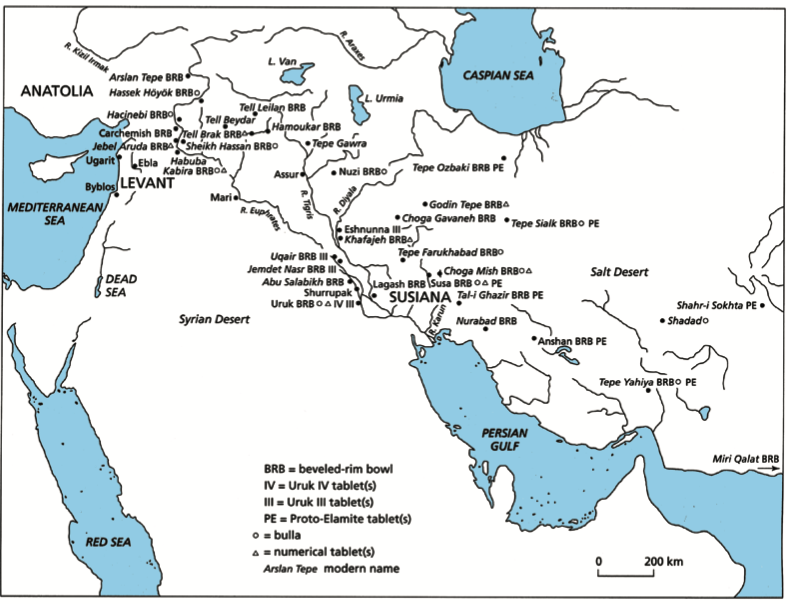

Figure 1: Map of the proto-cuneiform world (after van de Mieroop 2004: 36, map 2.2).

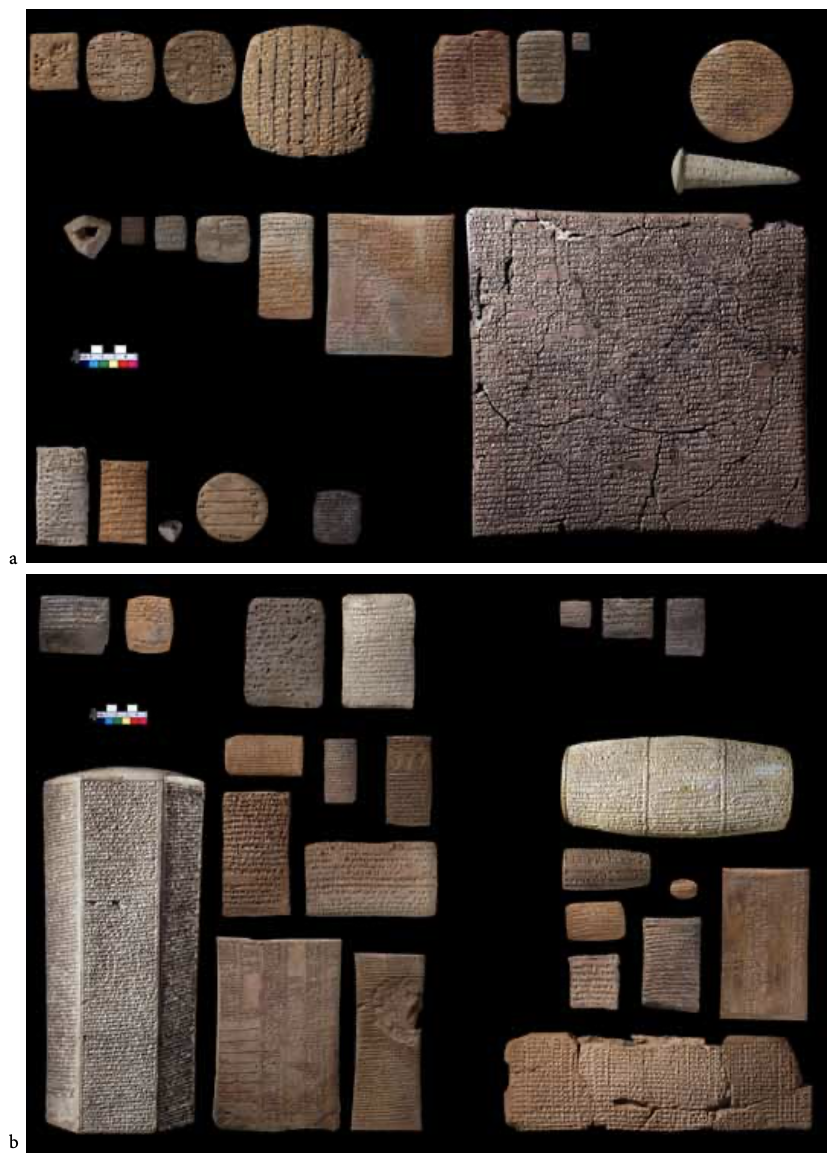

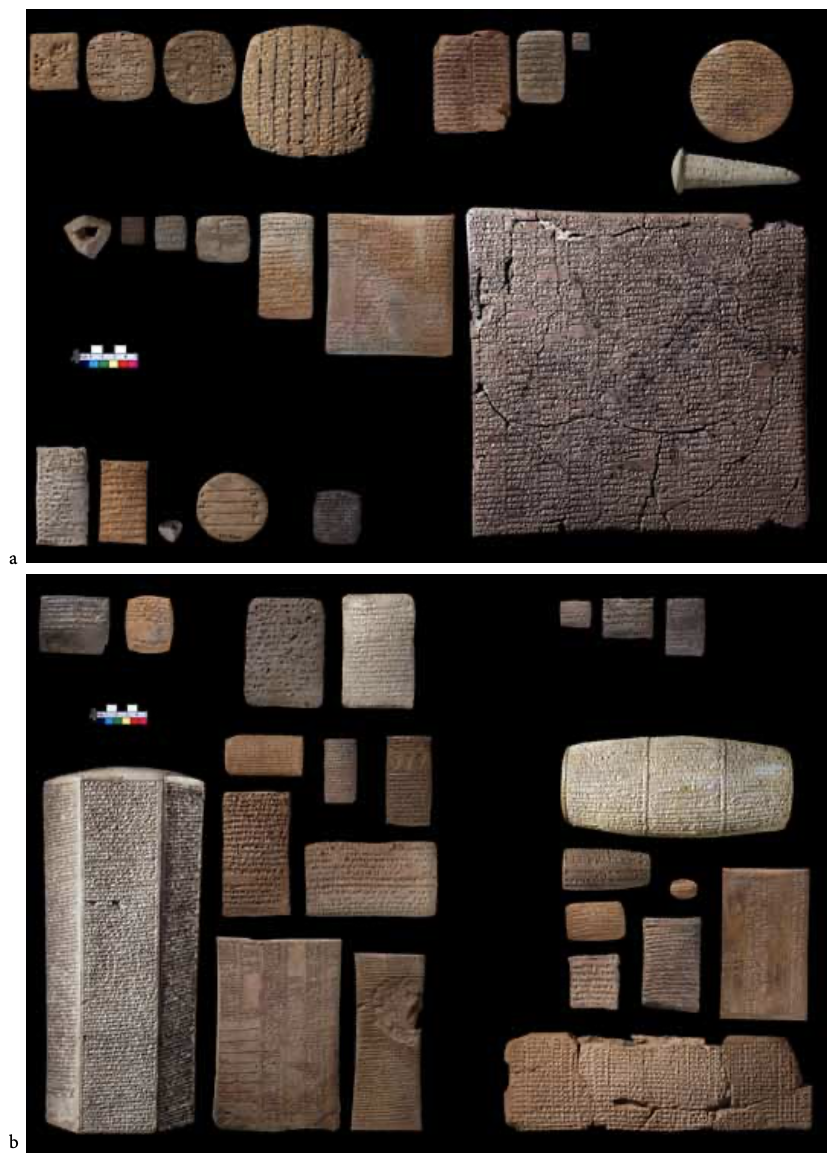

Figure 2: A sample of the variety of shapes and sizes of cuneiform texts on clay (after Taylor 2011: 9–10, figs 2A and 2). a) (Top) Archaic: administrative (BM 128826); Early Dynastic: administra- tive (BM 15829, BM 29996, BM 102081); Old Akkadian: administrative (BM 86281, BM 86289, BM 86332); Ur III: administrative (BM 24964), cone (BM 19528). (Middle) Ur III: adminis- trative (BM 19525, BM 104650, BM 13059, BM 19176, BM 26972, BM 26950, BM 110116). (Bottom) Old Babylonian: administrative (BM 16825), letter (BM 23145), administrative (BM 87373), scholarly (UET 6/3 64, on loan to the British Museum; Old Assyrian: administrative (BM 120548). © Trustees of the British Museum; b) (Top) Nuzi: administrative (BM 17616, BM 26280); Amarna letters (British Museum, ME 29883, ME 29785); Middle Babylonian: administrative (BM 17689, BM 17673, BM 17626). (Left) Neo-Assyrian prism (BM 91032), scholarly (British Museum, K 750), letter (British Museum, K 469), administrative (British Museum, K309a), scholarly (British Museum, K 159, K 195, K 4375, K 2811). (Right) Neo-Late Babylonian: barrel (BM 91142, BM 30690), administrative (BM 29589), scholarly (BM 92693), administrative (BM 30912, BM 30690), scholarly (BM 38104, BM 34580). © Trustees of the British Museum.