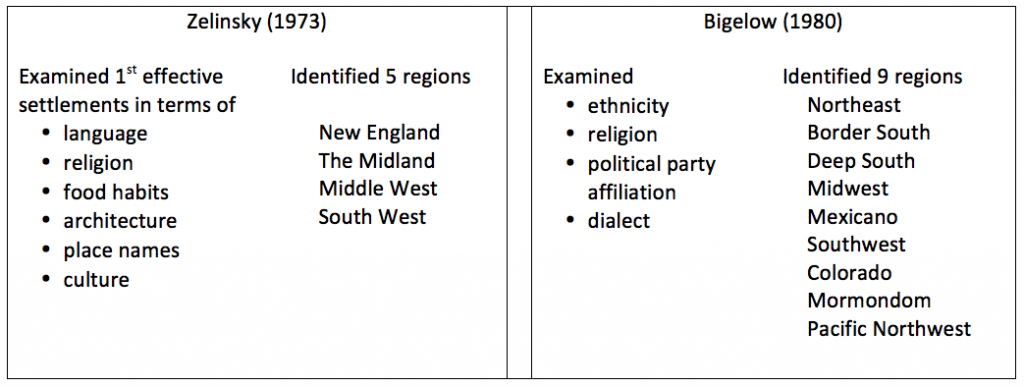

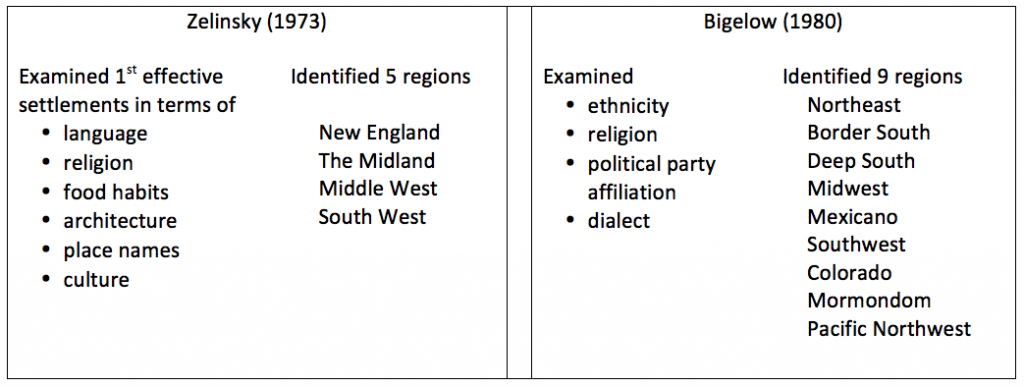

In 1831, 26-year old French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville toured the United States. Four years later, he published the first of two volumes of Democracy in America. At that time, Tocqueville saw the United States as composed of almost separate nations (Jandt, 2016). Since then, cultural geographers have produced evidence to support many of Tocqueville’s observations, noting that as various cultural groups arrived in North America, they tended to settle where their own people had already settled. As a result, different regions of the U.S. came to exhibit distinctive regional cultures. Zelinsky (1973) identified five distinctive cultural regions while Bigelow (1980) identified no fewer than nine. (See Table 8.1)

Table 8.1 Studies identifying U.S. regional cultures

Joel Garreau (1981), while an editor for the Washington Post, also wrote a book proclaiming that the North American continent is actually home to nine nations. Based on the observations of hundreds of observers of the American scene, Garreau begins The Nine Nations of North America by urging his readers to forget everything they learned in sixth-grade geography about the borders separating the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, as well as all the state and provincial boundaries within. Says Garreau:

Consider, instead, the way North America really works. It is Nine Nations. Each has its capital and its distinctive web of power and influence. A few are allies, but many are adversaries. Some are close to being raw frontiers; others have four centuries of history. Each has a peculiar economy; each commands a certain emotional allegiance from its citizens. These nations look different, feel different, and sound different from each other, and few of their boundaries match the political lines drawn on current maps. Some are clearly divided topographically by mountains, deserts, and rivers. Others are separated by architecture, music, language, and ways of making a living. Each nation has its own list of desires. Each nation knows how it plans to get what it needs from whoever’s got it. …Most important, each nation has a distinct prism through which it views the world. (Garreau, 1981: 1-2)

Historian David Hackett Fischer (1989) has argued that U.S. culture is best understood as an uneasy coexistence of just four original core cultures derived from four British folkways, each hailing from a different region of 17th century England. Most recently, journalist Colin Woodard (2011) drawing on the work of Fischer and others has identified eleven North American nations. In the sections that follow, I hope to show why essays like Althen’s may not be helpful for understanding American culture. In the process, I will briefly recount the story of the settling of North America for those who may not be entirely aware of that history.

Officially, of course, only three countries, Canada, the United States, and Mexico, occupy the entirety of North America, and each country began as a European project. The principal powers driving the settlement of the continent were England, France, and Spain. All three powers had a major presence in parts of what is now the United States before the U.S. assumed its present shape.