12.3: Performing Gender Categories

- Page ID

- 150285

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

So if gender is not a “natural” expression of sex differences, then what is it? Cultural anthropologists explore how people’s ideas of gender are formed in their minds, bodies, social institutions, and everyday practices.

Nature, Culture, and the Performance of Gender

Gender not only influences how people think about themselves and others; it also influences how they feel about themselves and others—and how others make them feel. Romantic or sexual passion draws from gendered identities and reinforces them. In the words sung by Aretha Franklin, “You make me feel like a natural woman.” There is something about gendered identity that can feel deep and real. The sense that some trait is so profoundly deep and consequential that it creates a common identity for everyone who has that trait is called essentialism. Gender essentialism is the basis of a lot of circular thinking. When a boy kicks a ball through the neighbor’s window and someone says, “Boys will be boys!”—that’s essentialist. You may be familiar with this little essentialist ditty from Euro-American culture:

Sugar and spice and everything nice,

that’s what little girls are made of.

Snips and snails and puppy dog tails,

that’s what little boys are made of.

In this view, gender is what you’re “made of”—that is, your biological essence.

And yet, biology and archaeology have shown that gender differences are complicated and illusory. What is a natural woman . . . or a natural man? Cultural anthropologists find that some cultures consider men and women to be quite similar, while other cultures emphasize differences between genders. All cultures promote a distinctive set of ideal norms, values, and behaviors, considering those ideals to be natural and good. In cultures that consider men and women to be similar, those ideals apply equally to all people. In cultures that consider men and women to be quite different, one set of ideals applies to men and another set applies to women. In all cases, the content of those ideals varies enormously across cultures.

Cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead conducted research on gender in several societies in New Guinea. She confessed that she had initially assumed that gendered behaviors were grounded in biological differences and would vary only slightly across cultures. In her 1935 book, Sex and Temperament, she describes her surprise at discovering three cultural groups with vastly different interpretations of gender. Among the Arapesh and Mundugumor, men and women were considered temperamentally quite similar, with little acknowledgment of emotional or behavioral differences between them. The Arapesh valued cooperation and gentleness, expecting everyone to show tolerance and support for younger and weaker members of the group. In contrast, among the Mundugumor, both men and women were expected to be competitive, aggressive, and violent. Among the Tchambuli (or Chambri), however, men and women were assumed to be temperamentally different: men were seen to be neurotic and superficial, while women were thought of as relaxed, happy, and powerful. While Mead’s dramatic findings have been subject to criticism, subsequent analysis and fieldwork by other anthropologists have largely substantiated her main conclusions (Lipset 2003).

Like race, gender involves the cultural interpretation of biological differences. To make things even more complicated, the very process of cultural interpretation alters the way those biological differences are perceived and experienced. In other words, gender is based on a complex dynamic of culture and nature. Gender identities feel more natural than, say, class or religious identities because they involve direct reference to one’s body. Most people’s bodies feel “natural” to them even with the knowledge that culture shapes the way individuals experience their bodies. In this way, gender is not so much natural as it is naturalized, or made to seem natural.

In the past three decades, many gender scholars have argued that gender is not so much a set of naturalized categories to which people are assigned as it is a set of cultural identities that people perform in their daily lives. In her influential book Gender Trouble (1990), philosopher Judith Butler describes gender as a kind of relation between categorical norms and individual performances of those norms. In childhood, people are presented with the idealized categories of male and female and taught how to enact the category to which they have been assigned. For Butler, gender is “an impersonation” because “becoming gendered involves impersonating an ideal that nobody actually inhabits” (1992).

If gender involves both established categories and everyday performances, then it’s necessary to pay close attention to the idealized norms of gender constructed in a particular cultural context and the various ways in which people enact those norms in practice. In Gender and Sexuality in Muslim Cultures (Ozyegin 2015), researchers studying Muslim communities in Turkey, Egypt, Pakistan, Syria, and Iran examine the ideals of Muslim masculinity and femininity in those contexts, as well as how those ideals are enacted and resisted in everyday life. Salih Can Açıksôz describes how the Turkish government provides disabled veterans with access to assisted reproductive technologies so that they can father children. The aim of this program is to make them feel like “real men” again, renormalizing their masculinity in the context of heterosexual family life. Maria Frederika Malmstroöm shows how Muslim women in Cairo strive to achieve the purity and cleanliness associated with femininity through such practices as cooking, skin care, and becoming circumcised. The idea is that gender is not at all “natural”; you have to work at it every day and make sure you’re doing it right. If you cannot seem to approximate your gender norm for some reason, then your family members, friends, and even the government may step in to help you perform it.

Women and Feminist Theories of Gender

Inspired by the women’s movement of the 1960s, many female anthropologists in the early 1970s began taking a critical look at mainstream American anthropology, noticing how the discipline focused almost exclusively on the activities of men—both as researchers and objects of study. In most early and mid-20th-century ethnographies, men were represented as the major social actors, and men’s activities were assumed to be the most important ones. Where were the women, and what were they doing? Calling for an “anthropology of women,” many feminist anthropologists set out to correct the ethnographic record by focusing more on the voices, perspectives, and practices of women in cultures all over the world.

Examining the roles of women in many cultures, feminist anthropologists began to see some patterns. In contexts where women made strong and direct contributions to subsistence, they seemed to enjoy greater social status and equality with men. Among gatherer-hunters, for instance, where women’s gathering activities provided the majority of calories in the overall diet, women held positions of equality. In contexts where women were relegated to the home as housekeepers and mothers, they were more subordinate to men and were not considered equal actors in sociocultural activities. Agricultural and industrial societies both created “public” spheres of work separate from the “private” sphere of the household. Women in these societies were more often assigned to work in the private sphere and sometimes even prohibited from entering public areas.

In capitalist market systems, the domestic work of housewives is uncompensated and virtually invisible. Cultural anthropologist Michelle Rosaldo (1974) argued that the division of sociocultural life into public and private spheres resulted in the marginalization of women.

While this early wave of feminist anthropology focused on women, more recently researchers have questioned the essentialism of this approach. Is gender always the most important factor in determining the status of women in all cultures? Gender intersects with race, class, ethnicity, age, sexuality, and physical ability to make the experiences of women diverse and complex, a position called intersectionality. Due to economic necessity, women of color in American society have more often been forced to work outside the home. In fact, many privileged White women have been able to hire domestic workers to relieve them of their household chores—and often those domestic workers have been women of color. For cooks, nannies, and housekeepers, the private domestic sphere of privileged women constitutes their own public sphere of work, supervised by the woman of the house. The experiences of people of color complicate the idea that women are subordinated through their confinement to the private domestic sphere.

Men and Masculinities

While men had been the primary focus of anthropological research up to the 1970s, they had always been studied as general representatives of their cultures. The establishment of gender studies in anthropology prompted both male and female anthropologists to view all persons in a culture through the lens of gender. That is, men began to be seen as not just “people” but people who are socialized and culturally constructed as men in their societies (Gutmann 1997). In the 1990s, a wave of scholarship emerged probing the identities of men and the features of masculinity across cultures.

Cultural anthropologist Stanley Brandes (1980) studied how men in Monteros, an Andalusian town in southern Spain, used folklore to express their ambivalent feelings of desire and hostility toward women. Through their jokes, pranks, riddles, wordplay, nicknames, and dramas, men in Monteros built camaraderie and constructed a male-centered ideology of dominance. A good part of each man’s day in Monteros was devoted to telling jokes and playing pranks among other men. Many jokes expressed fears about the sexual power of women, in particular the ability of women to seduce and destroy their male victims. Brandes provides a revealing example of one such symbolic joke:

A woman was walking along the streets of Madrid holding a dog in her arms so that it wouldn’t get run over. She was beautiful, the woman, and a man walking alongside her said, “If only I were that dog, there in your arms!” Responded the woman, “I’m taking him to have him castrated. Want to come along?” (1980, 105)

Research on masculinity demonstrates that “male” is not a stand-alone category but is always held in opposition to “female,” even when women are not present.

Other studies of masculinity have focused on the construction of masculinity through initiation rites, friendships, marriage, and fatherhood. Studying fatherhood among the Aka of central Africa, Barry Hewlett (1991) discovered that fathers in these communities are remarkably affectionate, attentive, and involved in the care of their children. Among families with young children, fathers spend 47 percent of their day within arm’s length of their children and frequently hold and care for them, especially in the evenings. Ethnographic research suggests that men are not “naturally” awkward or inept at childcare, nor are they less able to forge intimate and emotional bonds with their children. Rather, men are socialized to perform specific versions of fatherhood as proof of their masculine identities.

With the inclusion of masculinity, the anthropological study of gender came to be dominated by the opposed categories of male and female. Many studies take it as given that people are assigned at birth to one of these two categories and remain in their assigned category for a lifetime. A significant number of people in every culture, however, are not obviously male or female at birth, and some people do change their gender identities from one category to another—or even to an entirely different gender category that is neither male nor female.

Intersex and the Ambiguities of Identity

A friend tells you, “My sister just had a baby last night!” You respond, “Is it a boy or a girl?” Your friend replies, “Well, they don’t know. Maybe neither, maybe both.”

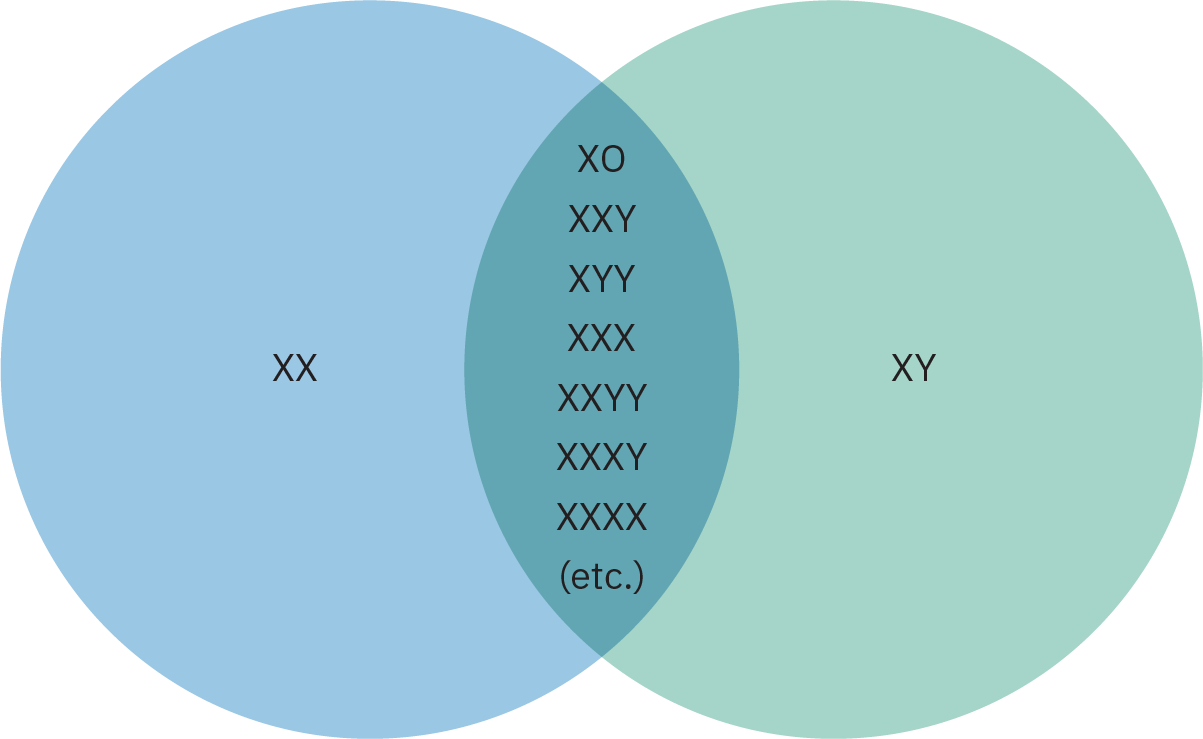

Based on a detailed analysis of extensive data, Anne Fausto-Sterling (2000) concluded that in about 1.7 percent of births, a baby’s sex cannot be completely determined just by glancing at the baby’s genitalia. (Note that due to different or changing considerations of sex determination, you may see different percentages or other differences in information; this text is using the most widely accepted and adopted research.) Intersex is an umbrella term for people who have one or more of a range of variations in sex characteristics or chromosomal patterns that do not fit the typical conceptions of male or female; the prefix inter- means “between” and refers here to an apparent biological state “between” male and female. There are many causal factors that can make a person intersex. Genetically, the baby may have a different number of sex chromosomes. Rather than two X chromosomes (associated with females) or one X and one Y chromosome (associated with males), babies are sometimes born with an alternative number of sex chromosomes, such as XO (only one chromosome) or XXY (three chromosomes). In other cases, hormonal activity or even chance occurrences in the womb can affect the baby’s anatomy.

While it is true that the majority of humans display biological characteristics associated with either one sex or another, 1.7 percent is not insignificant. If that percentage were applied to the global total of about 140 million babies born every year, it would mean that that more than two million of these babies could be intersex. On a more local level, if that percentage were applied to any town of 300,000 people, there could be more than 5,000 intersex people.

Beyond biology, the category of intersex reveals a great deal about the cultural mechanisms of gender. Intersexuality can be recognized at any point in a person’s life, from infancy to well into adulthood. Parents often discover their child is intersex in a medical context, such as at birth or during a subsequent visit to the pediatrician. When a doctor explains that a child is intersex, parents may be confused and concerned. Some doctors who are uncomfortable with biological sex ambiguity may order tests to determine the child’s chromosomal count and hormone levels and take measurements of the child’s genitals. They may urge parents to assign a specific gender to the baby and commit to plans for hormonal treatments and surgical interventions to affix that assigned gender to the growing child. Doctors are often taught to present the chosen gender as the “real” underlying sex of the baby, making medical treatment a process of allowing the baby’s “natural” (meaning unambiguous) sex to emerge. This conceptualization of intersex babies as “really” either male or female contradicts the complex mix of male and female traits presented by most intersex bodies (Fausto-Sterling 2000).

Fausto-Sterling disagrees with the practice of immediately affixing a sex to intersex babies through medical interventions. She argues that gender identity emerges in a complex interplay between biology and culture that cannot be assigned or controlled by doctors or parents. In an interview with the New York Times, she explained her position:

The doctors often guess wrong. They might say, “We think this infant should be a female because the sexual organ it has is small.” Then, they go and remove the penis and the testes. Years later, the kid says, “I’m a boy, and that’s what I want to be, and I don’t want to take estrogen, and by the way, give me back my penis.”

I feel we should let the kids tell us what they think is right once they are old enough to know. Till then, parents can talk to the kids in a way that gives them permission to be different, they can give the child a gender-neutral name, they can do a provisional gender assignment. (Fausto-Sterling 2001)

Many intersex people support a ban on what they call intersex genital mutilation, or IGM. In an article for HuffPost, Latinx intersex author and activist Hida Viloria (2017) calls attention to the hundreds of intersex people who have come forward to say that IGM has harmed them. The underlying goal of sexual assignment surgery, Viloria points out, is to create bodies capable of heterosexual sex. Medical ethicist Kevin Behrens (2020) argues that surgical interventions should only be carried out when surgery serves the best medical interests of the child and, in most cases, medical intervention should be delayed until the intersex person is old enough to give informed consent. Behrens also emphasizes that parents and children have the right to know the truth about an intersex child’s diagnosis and the possible consequences of any suggested treatment.

Intersex ambiguity and the rush to hide or eliminate it reveal important lessons about biology and culture. The process of determining what an intersex person was “meant to be” often involves a large set of biological variables, many of them subject to change over time. Those factors vary not only for intersex people but for everyone. Chromosomes alone do not make females and males. Rather, the interactions of genetic factors with hormones and environmental forces produce a complex continuum of gender. Instead of a binary of male and female separated by a hard boundary, many gender scholars recognize gender as a multidimensional spectrum of differences. There is far more biological variation within the cultural categories of male and female than between the two. This is not to deny the existence of biological differences but rather to complicate the concepts of sex and gender, allowing for the normalcy of ambiguity and the tolerance of variation.

Multiple Gender and Variant Gender

Many societies construct additional categories between male and female to accommodate people who do not fit into a binary gender system. The term multiple gender indicates a gender system that goes beyond male and female, adding one or more categories of variant gender to accommodate more sex/gender diversity. A variant gender is an added version of male or female that accommodates those who were not assigned to that category at birth but adopt that identity during the course of their lives. A person whose biology, identity, or sexual orientation contradicts their assigned sex/gender role can adopt a variant-gender identity. For instance, a person might be considered female at birth but later transition to a masculine version of female—what anthropologists term female variant.

Cultural anthropologist Serena Nanda (2000) has studied variant-gender categories in many societies, including Native North American societies and peoples in Brazil, India, Polynesia, Thailand, and the Philippines. The widespread practice of multiple gender indicates a common cultural need to accommodate the complexities of human sex/gender and sexuality. In contrast, European and Euro-American societies have inherited a rigid two-gender system that stigmatizes people who do not conform to the gender identity assigned to them at birth. Activists pressing for more gender flexibility can be inspired by examples of alternative gender in many non-European cultures.

When Spanish explorers first came to North America, they were astonished to find men in Native American societies who dressed as women, did the work of women, and had sexual relationships with men. Later, anthropologists who studied Native American groups discovered that some groups, including the Crow and the Navajo, had categories of variant male (assigned a male identity at birth but adopting a feminine identity later on) and variant female (assigned female at birth but adopting a masculine identity later on). Note that people in variant categories did not fully transition to the opposite gender but rather took on a masculine or feminine variant of the sex assigned at birth. Ignoring the Native American terms for variant gender, early European explorers referred to variant males as berdache, a Portuguese term that indicated a male prostitute—though that is not what they were at all. In 1990, as Native American LGBTQ people sought to resurrect their heritage of variant gender, they coined the pan-Indian term two-spirit people, meaning people with both male and female spirits.

Two-spirit people were highly valued and esteemed in Native cultures. Rather than facing stigma or rejection, their alternate gender identity was thought to give them special talents and spiritual powers. In many Native American societies, two-spirit people often became healers and spiritual leaders. They were typically very successful at performing the work of the opposite gender. Male-variant people were known for their excellent cooking and needlework, and many female-variant people were great hunters and warriors. Two-spirit people were also called upon to act as intermediaries between genders, such as in marriage arrangements.

Like gender-nonconforming people in many societies, two-spirit people began to realize their variant identities in childhood, rejecting the activities associated with their assigned gender. A boy might want to cook or weave, or a girl might prefer to hunt and play with the boys. If there were not enough boys to hunt, a family might even encourage a girl to develop a variant identity so that she could help provide meat to the family. Sometimes, children would experience visions or dreams guiding them to the tools associated with the opposite gender.

Generally speaking, people of variant gender had sexual relationships with people of the gender opposite their lived identity. So if a person took on the clothing and work of a woman, they would be expected to have intimate relationships with men, and people who lived as men would have relationships with women. Neither two-spirit people nor their opposite-gender partners were considered lesbian or gay.

With European colonization of North America came a much more restrictive system of gender categories and sexualities. As Euro-Americans expanded into Native American territories, Native Americans were pressured to assimilate to Euro-American norms. From 1860 to 1978, children were removed from their families and sent to assimilationist schools, where they were taught that Native cultures were backward and variant genders were sinful and deviant. By the 1930s, variant-gender practices had largely disappeared. However, with the rise of the American LGBTQ movement, many Native Americans have rediscovered the more flexible and tolerant gender system of their ancestors.