15.4: Visual Anthropology and Ethnographic Film

- Page ID

- 150317

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Although the subfield of media anthropology is relatively new, anthropologists have been incorporating media technologies into their methods of research and ethnographic representation since the early 20th century. An early pioneer of visual methods, Margaret Mead took some 200 photographs as part of her first fieldwork project in Samoa (Tiffany 2005). In the 1930s, Mead and Gregory Bateson used both photography and film in their joint fieldwork in Bali and New Guinea. Mead and Bateson embraced visual media as an innovative means of learning about social life and used photos and film to study childhood, public ceremonies, and dance. Together, they took about 33,000 photographs and recorded about 32,600 feet of film as part of their joint research (Jacknis 2020). Focusing on child development and dance, they used these visual materials to produce two photographic ethnographies and seven short films.

Visual anthropology is either the use of visual media as a research method or its study as a research topic. Whether they consider themselves visual anthropologists or not, most anthropologists take photos of the people and places they encounter in their fieldwork. Visual anthropologists go further, using photography and film to document important events for fine-grained future analysis. As moments frozen in time, photographs allow for analytical contemplation and shared consideration. Film can be slowed down or sped up to focus on certain aspects of individual action or group dynamics that might otherwise go unnoticed. Images may be magnified to reveal minute details. Both film and photography allow for images to be placed side by side for comparison.

Visual anthropologists are also interested in how people in the cultures they study produce their own visual representations in the form of art, photography, and film. Visual anthropologists are interested in popular paintings, billboards, and graffiti as well as forms of photography and film.

Early on, cultural anthropologists recognized that visual media made it possible to share the experiences encountered during anthropological research with their colleagues and students, and the general public. One example of many is the film Trance and Dance in Bali (1951), written and narrated by Mead, which features a Balinese dance called the kris. The kris dance dramatizes the story of a witch whose daughter is rejected as a bride to the king. In retaliation, the witch plots to spread chaos and pestilence in the land. When the king sends an emissary with a convoy of servants to stop the nefarious plan, the witch turns the emissary into a dragon. She then causes the followers of the dragon to fall into trance. When the dragon-emissary revives his followers, they emerge in a somnambulant state, stabbing themselves with daggers but inflicting no harm. After dancing the kris dance, the dancers are brought out of their trance with incense and holy water. Included in the US Library of Congress, this stunning early use of film in anthropology can be viewed at the Library of Congress website or on YouTube.

Ethnographic film is the use of film in ethnographic representation as either a method, a record, or a means of reporting on anthropological fieldwork. Like documentary films, ethnographic films are nonfiction films in which live-action shots are edited and shaped into a central narrative drama. While the line between documentary and ethnographic film is blurry, ethnographic film is associated with the work of professional anthropologists and tends to focus explicitly on depictions of sociocultural processes.

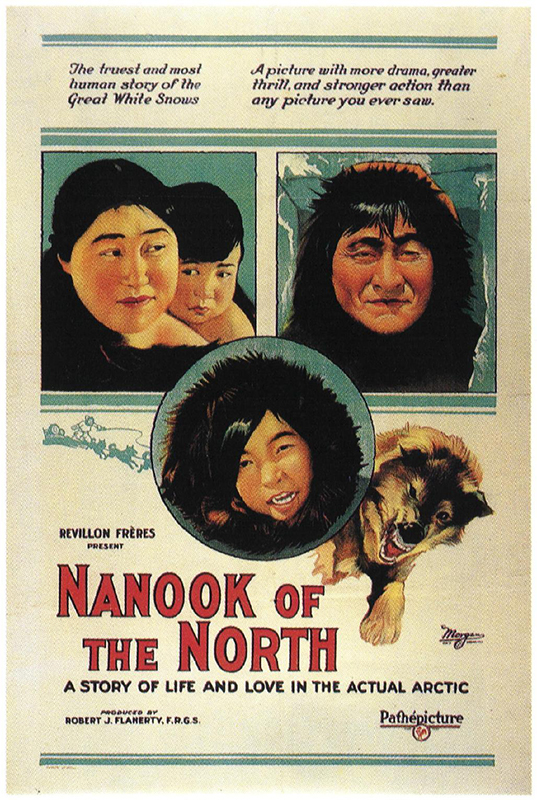

Before Mead and Bateson’s professional use of film, several filmmakers had made amateur ethnographic films depicting aspects of non-Western cultures. The very popular film Nanook of the North (1922), made by explorer Robert Flaherty and based on 16 months of living with the Inuit, follows an Inuit family in the Canadian Arctic. The film focuses on the heroism of husband Nanook and wife Nyla as they struggle against the harsh elements to meet their needs and raise their children. The film documents Inuit lifeways such as traveling by dogsled and kayak, hunting walrus, and building an igloo out of glacier ice. In one controversial scene, the family visits a Canadian trading fort, where they express astonishment at instruments of modernity such as a phonograph. Though the film has been praised for its representation of Indigenous peoples as courageous and hardworking, others have criticized Flaherty for staging some of the events and even having his own common-law wife play the role of Nanook’s wife in the film. Like Mead and Bateson’s film, Nanook of the North is now held by the Library of Congress as one of the most significant examples of early documentary filmmaking. While some consider Nanook to be a precursor to ethnographic film, anthropologist Franz Boas dismissed it as completely irrelevant to anthropology due to Flaherty’s use of artifice and staging (Schäuble 2018). The film can be viewed at the Internet Archive or on YouTube.

From its roots in both amateur and professional filmmaking, ethnographic film became an increasingly important tool for teaching and popularizing anthropological research throughout the 20th century. In the 1950s, John Marshall and Timothy Asch pioneered a more objective, naturalist style of ethnographic film, attempting to avoid Western narratives and exoticization. With the development of the ability to simultaneously record sound in the 1960s, the commentary and conversations of people represented in ethnographic films became audible (even if translations still appeared in subtitles). Subjects could now address the camera directly. Around the same time, anthropologists began considering the power dynamics embedded in the production of ethnographic film—in particular, the ethical issues involved in White Western researchers controlling the representation of non-Western peoples.

Responding to these ethical challenges, many ethnographic filmmakers have turned away from the heavily crafted narrative methods of films such as Nanook toward a more purist style that represents unfolding action with little editing. New methods of representation have emerged, revealing the very act of filming itself and highlighting the relationship between filmmakers and those being filmed. Rather than using film as a means of teaching anthropology to students and the public, some experimental filmmakers conceptualize film as the creation of an entirely new sociocultural experience. The experimental ethnographic film Manakamana, for instance, directed by Stephanie Spray and Pacho Velez and released in 2013, comprises 11 long shots of Nepalese pilgrims taking cable car rides to a mountaintop temple in Nepal. Rather than teaching the viewer about an anthropological topic, Manakamana provides live-action portraits of people and their relationships against the backdrop of the rugged landscape passing below them. Spray and Velez are collaborators in Harvard University’s Sensory Ethnography Lab, a project dedicated to the experimental use of multisensory methods to create ethnographic media. You can view a trailer for the film on YouTube.