11.4: Communication as a Weapon—Aggression in Relationships

- Page ID

- 136583

Types of Verbal and Physical Aggression

Christine showed up to school on Monday with a split lip and laughingly told her friends that her dog head-butted her while they were playing. It was not until several months later that she confided in her best friend that her boyfriend has been criticizing her over every little thing, picking fights, and belittling her and that he was the one who caused her split lip. Unfortunately, aggressive occurrences such as this are not uncommon in personal relationships. According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (2021), almost 49% of adults have experienced some kind of aggressive behavior from an intimate partner. Our personal relationships with friends, family and romantic partners are supposed to be our safe haven, a place of security that enhances our well-being. However, as we have seen previously in this chapter, every light side can be accompanied by a dark side, and in this case, the relationships that should keep us safe may also cause us harm when they are plagued by aggression. In this section, we focus on several different types of aggression, including verbal aggression, physical aggression, bullying, psychological abuse, and intimate partner violence. We wrap the section up with resources for help if you or someone you know is being harmed.

Verbal Aggression and Abuse

Emma is a member of her school’s soccer team. After one particularly competitive game, she came home in tears. Her mother asked about her tears and Emma shared that the coach screamed at her in a profanity-laced rant, humiliating her in front of her teammates. Emma’s mother responded with appropriate empathy and concern, and told Emma that she thought the coach was being verbally abusive. Verbal abuse is a pattern of speaking that includes a specific intent to demean, humiliate, blame or threaten the relational partner. Verbal aggression involves attacking the self-concepts of the other party using insults, character attacks, harsh teasing, and profanity (Hocker & Wilmot, 2018). According to the book The Verbally Abusive Relationship (Evans, 2010), many victims of verbal abuse do not realize that it is harmful, and a form of abuse. It is important to learn recognize verbal abuse and aggression and recognize that ongoing verbal aggression and abuse can lead to psychological trauma (NCADV, 2015).

According to the National Network to End Domestic Violence (WomensLaw.org, 2021), some examples of verbal and emotional abuse may include an individual

- Acting jealous and constantly accusing you of cheating.

- Getting angry in a way that scares you.

- Calling you insulting names like “stupid,” “worthless,” and “disgusting.”

- Threatening to call authorities to report you for wrongdoings.

- Deciding things for you that you should decide (like what to wear or eat).

- Humiliating you in front of others.

- Continually pretending to not understand what you are saying, making you feel stupid, or refusing to listen to your thoughts and opinions.

Types of Verbal Abuse

Patricia Evans (2010), author of the book The Verbally Abusive Relationship, found through her research and conversations that many different types of verbal abuse can exist in a relationship. The following are the most commonly identified types of verbal abuse:

- Hostile withholding: Abusers may refuse to acknowledge the partner’s existence for hours, days, and sometimes longer, which can lead to a partner feeling isolated and desperate for the abuser’s approval and acknowledgment. For example, Jun is frustrated when her best friend Jasmin starts to give her the silent treatment, leaving her text messages unread, and ignoring her at school, even though they have an important project to finish.

- Countering: When the abuser tries to convince their partner that their feelings about anything and everything are wrong. Although it is normal for people to disagree at times, countering occurs when the abuser responds with hostility to your opinions and ideas, even if they agree with you. To illustrate, while Rosario is helping her dad wash the family car, she comments on a beautiful car that drove by. Her father responds with hostility, accusing her of being materialistic, saying that he would never be caught dead in such a car. Rosario is left in tears and bewildered by the attack.

- Discounting or jokes: Telling a partner that their emotions are wrong, denying them the right to simply feel what they feel, or indicating it was “just a joke” to discount the other person’s feelings. For example, if you find yourself feeling hurt as a result of your partner’s comment, and then your partner says “I was just joking.”

- Blocking. The abuser will prevent the partner from talking at all, cutting them off or accusing them of talking out of turn so they are effectively silenced.

- Blame. The abuser will blame the other person as a degradation or humiliation tactic, such as telling their partner they’re not able to make friends because they’re a bad person or bad things happen to them because that’s what they deserve.

- Judging and criticizing. Similar to blame, the abuser will judge the partner unfairly for just about everything which impacts their self-esteem. For example, the abuser may frequently say something like, “Why are you so slow? You always ruin it for us when we go anywhere.”

- Trivializing. An abuser will minimize a partner’s accomplishments. For example, the abuser may trivialize an award received by their partner by saying, “Wow, the competition must have been bad this year.”

- Undermining. An abuser will make sure to question a partner at every turn in a conversation. This can lead to the partner not lacking confidence in any accomplishments. For example, if your boss publicly questions every decision you make on a project, while privately telling you they want you to take more initiative, they may be undermining you.

- Name calling: This can be blatant or in terms of subtle references in conversations such as “Of course, only a loser would do something like that” or “Hey idiot—take a look at this.”

In the 2018 movie I, Tonya, which is a dark biographical reveal about Tonya Harding, a polarizing US figure skater in the early 1980s, we see many depictions of Tonya with two abusers in her life: her mother and her husband. Tonya’s mother is both physically and verbally abusive to her. In many situations, she engages in hostile withholding (where she withholds affection from Tonya as a way to manipulate her) or judges and criticizes before her competitions (under the delusion that Tonya will skate better this way if she is angered prior to taking the ice), or trivializes her accomplishments in order to make Tonya feel less than—all of which significantly impact Tonya Harding’s self-esteem and ultimately contribute to her downfall in the figure skating world.

Be Aware of DARVO

In situations involving communication abuse, such as gaslighting or verbal aggression, it is common for the abuser to respond in a way that tries to deny or evade accountability and flip the responsibility back to the victim. As listed in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), DARVO is used by people who cause harm to minimize and effectively silence those who have experienced harm. These tactics, known as DARVO, are used by people who cause harm to minimize and effectively silence those who have experienced harm (Freyd, 1997). According to Jennifer Freyd, “The perpetrator or offender may Deny the behavior, Attack the individual doing the confronting, and Reverse the roles of Victim and Offender such that the perpetrator assumes the victim role and turns the true victim into an alleged offender” (1997). Defensiveness and denial are key aspects of how an abuser or perpetrator will use DARVO to escape being held accountable for their communicative actions. Unfortunately, the use of DARVO as a way of victim-blaming can serve to further silence relational partners and undermine their credibility when speaking out against an abuser (Harsey, et al., 2017). It is important to be aware of DARVO, as these common response tactics can cause relational partners to doubt their own perception of what is occurring in the relationship, which can enable the verbal abuse cycle to continue.

Verbal abuse and aggression can be very subtle and rarely leave signs of visible damage, nonetheless, the harm to an individual's self-esteem and overall well-being can be severe. Communication aggression can go beyond close relationships and take on a social element when teams or groups attack individuals.

Social Aggression and Bullying

Social aggression is “directed toward damaging another’s self-esteem, social status, or both, and may take direct forms such as verbal rejection, negative facial expressions or body movements, or more indirect forms such as slanderous rumors or social exclusion” (Galen & Underwood, 1997, p. 589). At its core, social aggression is an attempt to hurt someone by inflicting harm on their friendships and social status, and can include behaviors such as malicious gossip, manipulation, and exclusion from social groups (Underwood, 2004). A Girl Like Her is a 2015 movie about a high school student who uses a hidden camera to document her own bullying by her former best friend. The storyline is based on the phenomena of social aggression, where a character used threats, intimidation, gossip, and slander to retaliate against a former best friend. Furthermore, like the characters in the movie, research suggests that although boys and girls participate in social aggression, males are more likely to use physical aggression and females are more likely to use social aggression (Lansford, et al., 2012).

Social aggression exhibits aspects of both the dark and light sides of communication. Some of the harm caused by social aggression includes increased social isolation, loneliness, depression, anxiety, loss of performance in school, and increased suicide. Although it is easy to see the harm caused by social aggression, particularly during the adolescent and teen years, it is important to understand that social aggression may also serve some beneficial functions. It serves to promote individual identity formation (such as the establishment of a group leader), group identity (Dodger fans versus San Francisco Giants) and can be used to enforce cultural and peer values and norms (such as making fun of a friend who has not taken a shower in a little too long).

Bullying, a form of aggression among peers, can encompass the previously mentioned physical, verbal and social aggression, in addition to cyberbullying. However, what sets bullying apart from other forms of aggression is that it represents a pattern of aggressive attacks over time toward a targeted individual. Bullying includes physical and psychological harassment and is initiated by an individual toward someone with less power, whether it be physical strength or social status. Bullying can be one on one, or in some cases, many individuals can be responsible for harassment, known as mobbing (Hoover & Oliver, 2008).

Actor Josh Gad, of Frozen, shared his experiences of being bullied in high school:

I realized early on [that] I was the absolute poster boy for bullying because I struggled with being overweight from a very early age, but I also discovered that comedy was a weapon that I was able to employ," he said on Off Camera with Sam Jones. "I remember one time a kid calling me fat in front of, like, a group of people. And, instead of kowtowing and giving him the opportunity to sort of, you know, leave, I started reciting that monologue from My Cousin Vinny, where he walks in the bar and he sees the guy in the arm sling. And I just literally started reciting to the point that the guy's like, 'What the f--- is happening right now?' And everybody is laughing at him.

Anyone can be bullied. According to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (CDC, 2019), more than 30% of US high school students report being bullied in school. Transgender students report bullying in schools at even higher rates, up to 43%. Bullying of these individuals occurs due to a lack of tolerance and understanding for those who are perceived as different. It is easy to exclude and bully someone who can be “othered.” In the movie The Social Network, which depicts Mark Zuckerberg's rise with Facebook, there is a scene that talks about the impact of bullying, especially via social media platforms. In this scene, Zuckerberg’s friend describes how being cruel to a person’s face is like using a pencil, but saying something online is being cruel with a pen. They were emphasizing the permanency and impact of the dark side of bullying behavior, especially in the online space. Later on in this chapter, we will go into more depth about the dark side of social media's influences on communicative behavior.

The rise of anti-Asian sentiment and bullying increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic. A 2021 report by the STOP AAPI Hate Youth Campaign found that almost 75% of the 1100 students they interviewed about their experiences indicated cyberbullying and verbal harassment as forms of anti-Asian sentiment they had recently experienced. This increase has been greatly influenced by the coronavirus-related racism toward Asians that has been facilitated through the media and in communities where anxiety and fear have led to such stereotypical views about Asians.

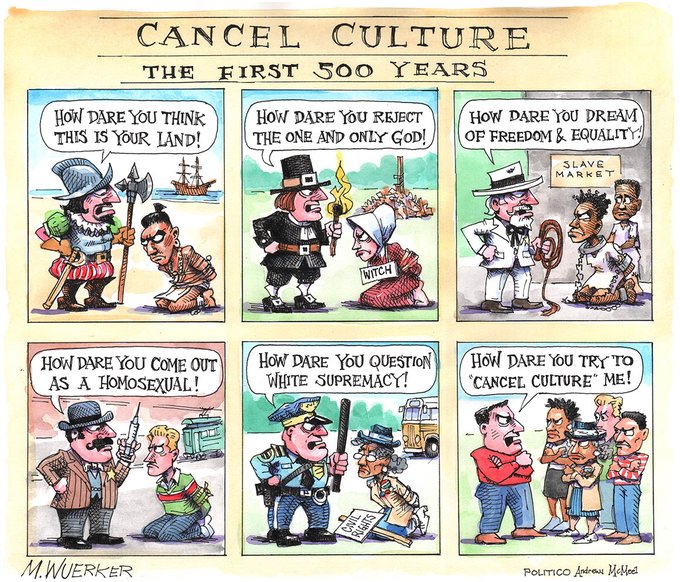

Now that we have examined different types of social aggression and bullying, take a moment to read about cancel culture. Next, we will to turn our attention to intimate partner violence (IPV). Verbal aggression, psychological abuse, and social aggression often occur before the first incident of IPV.

Cancel culture isn’t a new concept, but it has taken on a much more prominent role in our culture as technology and the internet have opened the floodgates for the public to express opinions and challenge each other’s views. The debates and discussions over what exactly is “cancel culture” was the focus of a survey conducted by Pew Research Center. The survey involved 10,093 US adults and was conducted in September 2020. The results found “a public deeply divided, including over the very meaning of the phrase” (Vogels et al., 2021).

The original idea of “canceling” had to do with marginalized communities asserting their values to hold public figures accountable (Romano, 2021). While most in the Pew survey described “cancel culture” as “actions people take to hold others accountable” (Vogels et al, 2021), it has evolved to include public shaming, callouts, and other forms of public backlash that attempt to seek social justice against anyone in disagreement via the many social media platforms accessible 24/7. For some, canceling others seems to address a power imbalance between people with money (celebrities, politicians) and the general public. Anne Harper Charity-Hudley, chair of linguistics of African America at the University of California, Santa Barbara explains,

When you see people canceling Kanye, canceling other people, it’s a collective way of saying, “We elevated your social status, your economic prowess, [and] we’re not going to pay attention to you in a way that we once did.... I may have no power, but the power I have is to [ignore] you.” (Romano, 2020)

Thanks to social media, many in the public have gained the power to voice their opinions and boycott or refuse to participate. “Canceling is a way to acknowledge that you don’t have to have the power to change structural inequity,” Charity-Hudley said. “You don’t even have to have the power to change all of the public sentiment. But as an individual, you can still have power beyond measure” (Romano, 2020).

Discussion Questions

- How does social media fuel cancel culture?

- How have perpetrators become “victims” in the cancel culture environment?

- How is cancel culture itself a target in the cancel culture environment?

- What are some examples of cancel culture you’re aware of? What “woke” your awareness of this person/issue?

- LeVar Burton argues that cancel culture is misnamed. Although he believes people should be held accountable, he argues it should be re-named as “consequence culture.” If you were working for a marketing agency tasked to rebrand the concept of cancel culture, what would you rebrand it as and why?

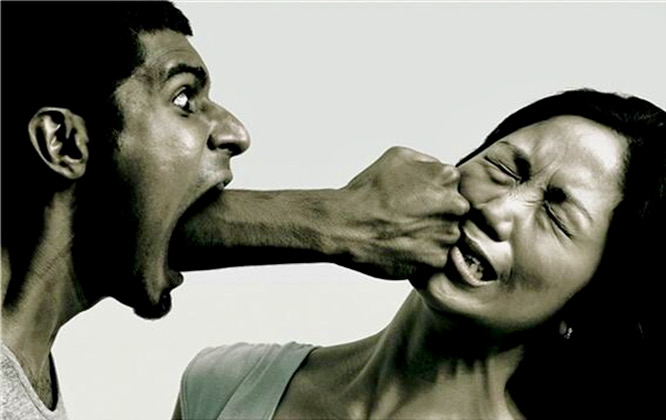

Physical Abuse and Intimate Partner Violence

In the spring of 2022, the world was captivated by Johnny Depp and Amber Heard's defamation trial. Detailed accounts of physical abuse and photographic evidence captured the brutality of the relationship of the Hollywood couple. This violent exchange shed light on the often untold story of intimate partner violence (IPV). IPV is often considered a subset of aggression but goes beyond verbal acts of aggression to include behavior where one person in a close relationship purposefully inflicts physical, emotional, psychological, or sexual harm on another person (Spitzberg, 2011; Evans, et al., 2020). Abuse can occur in many types of close relationships, such as between parent and child, siblings, and friends; however, IPV is distinguished by its occurrence in romantic relationships. Here is where the light versus dark side comes into view, as intimate relationships are supposed to be our most cherished, protected, and safe relationships, yet they can also be relationships that put us in the most danger. Although IPV impacts people of all races, cultures, genders, sexual orientations, socio-economic groups, and religious groups, it has a “disproportionate effect on communities of color and other marginalized groups. Economic instability, unsafe housing, neighborhood violence, and lack of safe and stable childcare and social support can worsen already tenuous situations” (Evans, et al., 2020).

A wide range of studies have examined the prevalence of IPV in romantic partner relationships. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey estimate that greater than 35% of women and 28% of men experience IPV in their lifetimes (Black, et al., 2011). A large-scale study asked 14,965 high school students. “During the past 12 months, did your boyfriend or girlfriend ever hit, slap, or physically hurt you on purpose?” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006). Of the participants, 8.8% of females and 8.9% of males replied yes. Research has found that emotional abuse, such as insults, swearing, and humiliation, are the most common forms of IPV across couples of various ages and that there is a direct link between the quality of communication and rates of IPV (Rada, 2020). When couples rate their communication quality as low or very low, all forms of IPV were higher, especially emotional abuse. Not surprisingly, married and romantic couples in early adulthood (ages 24–32) who rate their relationships as less satisfying also are more likely to indicate that their relationship is characterized by some forms of IPV (Ackerman & Field, 2011).

IPV includes a wide variety of physically aggressive and/or violent behaviors, including pushing, grabbing, slapping, and throwing items, to the more violent, such as choking, threatening or using a weapon such as a gun or a knife, hitting with an object, or beating. Although physical aggression is not as common as verbal or psychological aggression, research suggests that it occurs in one-quarter to one-half of all intimate partner relationships, including dating and marriage (Lawrence & Bradbury, 2007). It is important to note that the most violent acts are extremely rare in teen romantic relationships (Munoz-Rivas, et al., 2007).

There are several common myths about IPV. To better understand the role of violence in relationships, it is worthwhile to examine these misconceptions. Based on a review of research about IPV, Spitzberg (2011) highlights some important findings:

- Men are more likely to be victims of violence, usually at the hands of other men.

- Females use approximately equal or greater amounts of violence in their relationships than men.

- Women are more likely to be physically and psychologically injured.

- Self-defense accounts for a minimal amount of IPV.

- Men and women initiate relatively equal amounts of IPV.

- IPV tends to be reciprocal, meaning that when one person is physically abusive it can trigger a physically abusive response.

- IPV is rarely about power. In a review of the literature, Spitzberg and Cupach (2011) point out that IPV may be due to other factors, such as anger, jealousy, lack of control over emotions, and to get attention.

Being a victim of IPV, as well as verbal and emotional abuse, can have long-term consequences on both physical and psychological health including depression, anxiety, and even post-traumatic stress disorder. While support for victims is still limited in the workplace and public settings, there are lots of resources available for people who have experienced verbal and psychological abuse in domestic settings. If you or someone you care about is being impacted by verbal aggression or IPV please consider reaching out for help.

Have you ever witnessed or found yourself to be on the receiving end of the types of the communication behavior that we described in this section? These behaviors may be signs that someone is being verbally abusive and should be considered as red flags. In a later section in this chapter, we provide some resources you can seek out that help IPV (which includes both physical and verbal abuse). In the meantime, what can you do if you find yourself recognizing such behaviors and seeing a pattern of these occurring in your own relationship?

- The first step is to acknowledge to yourself that these behaviors are harmful and that they are signs of a dysfunctional relationship.

- Consider seeking help from a trusted adult, instructor, or the health center at your college.

- Set boundaries of what is acceptable communication between you and the abuser.

If you or someone you know is being impacted by IPV or other forms of abuse, please consider reaching out to one of these resources:

- California Partnership to End Domestic Violence (visit CPEDV.org or call 916-444-7163)

- Child National Abuse Hotline (800-4-A-Child)

- Futures Without Violence

- National Domestic Violence Hotline (visit TheHotline.org, text LOVEIS to 22522, or call 800-799-7233)

- National Parent Hotline (855-4A-Parent)