8.1: Our Emotional Experiences

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 90708

Learning Objectives

- Define emotions

- Differentiate between emotions and mood.

- Describe the physiological, cognitive, and social theories of emotions.

- Identify characteristics of different types of emotion.

You are about to get up to give a speech and you are really nervous. You may feel sick to your stomach, weak, dizzy, your heart might be racing. When you start giving your speech you start to feel better and by the time your speech is over and you sit down, you a relief washes over you—you are finished. The intensity that you felt before you gave the presentation (also called public speaking apprehension) was draining. What you experienced was an emotion. In this Module, we want to introduce you to human emotions and their characteristics.

What are Emotions?

We define emotions as our bodies responses and our interpretation of internal or external triggers that can either help or hinder our goals (Oatley, Johnson-Laird, 1996). There are many different definitions of emotion, but common ones include anger, sadness, and joy. Emotions are different from moods. Moods our general disposition or state of feeling. Moods can last for days. They have no specific cause or trigger.

For example, we have little problem identifying what specifically triggered our disgust. Perhaps it was the smelly diaper in the living room. But we might not be able to tell why we started out the day with such a poor outlook. We are almost certain that anything that we touch will not work. Sure enough, you burn the toast, put the car into the wrong gear, slip on the sidewalk and almost fall on your way to class, then spill your coffee on your papers you have to hand in, and then, when you finally get home from classes, you realize you locked yourself out of your apartment. We might just wake up one morning and feel like nothing will go right that day.

Moods are not usually intense enough to cause the physiological changes that emotions often do. When we experience emotions, they are intense and thankfully short-lived. For example, that feeling of anxiety that you felt before giving a speech probably dissipated after the speech was over, or if you found out that the speech was no longer required to be given. You would not keep that intensity of emotion for very long—experiencing intense emotion stresses the body and can be emotionally exhausting (Gaines, 1983). Table 1 below summarizes some key differentiating features between emotions and moods.

| Emotions | Moods |

|---|---|

| Specific trigger | No specific trigger |

| Quick | Slower to change or dissipate |

| High Intensity | Lower Intensity than emotions |

| Accompanied by sudden physiological changes | Little to no changes; changes might be more gradual |

Researchers have focused on seven basic emotions: joy/happiness; sadness; anger; disgust; contempt; surprise; and fear. These basic emotions are said to be primary emotions (Ekman & Friesen, 1986). Yet, only looking at these basic emotions is really oversimplifying what we humans actually experience. In other words, they are discrete and only made up of one emotion. Mixed emotions are opposite valences (one is positive, like joy, and one is negative like sadness) that are experienced simultaneously (Trampe et al., 2015).

For example, we may experience sadness but also joy when we reach a milestone like graduating from high school. We typically experience blends of emotions. Secondary emotions are made up of several primary emotions. An example would be when someone experiences jealousy in a romantic relationship. Jealousy is often a mixture of anger, fear of losing that person, and sadness or anxiety over the anticipation of that loss.

If we make a mistake during a job interview we may feel angry but also embarrassed because other people saw our mistake. Imagine that you earn an A on a chemistry exam, you may feel proud of a job well done, and also relieved that your studying paid off as well as happy that you can relax over the weekend instead of studying.

Dr. Paul Ekman, one of the world’s leading experts on emotion, showed the strongest evidence to date of the seven universal facial expressions of emotion. His studies explored people’s accuracy after viewing photographs of facial expressions (Ekman, et al., 1969). Facial expressions of disgust, for example, are easily and accurately recognized across cultures when identifying emotional expressions. Ekman’s research strongly suggests that there are certain emotions that are universal.

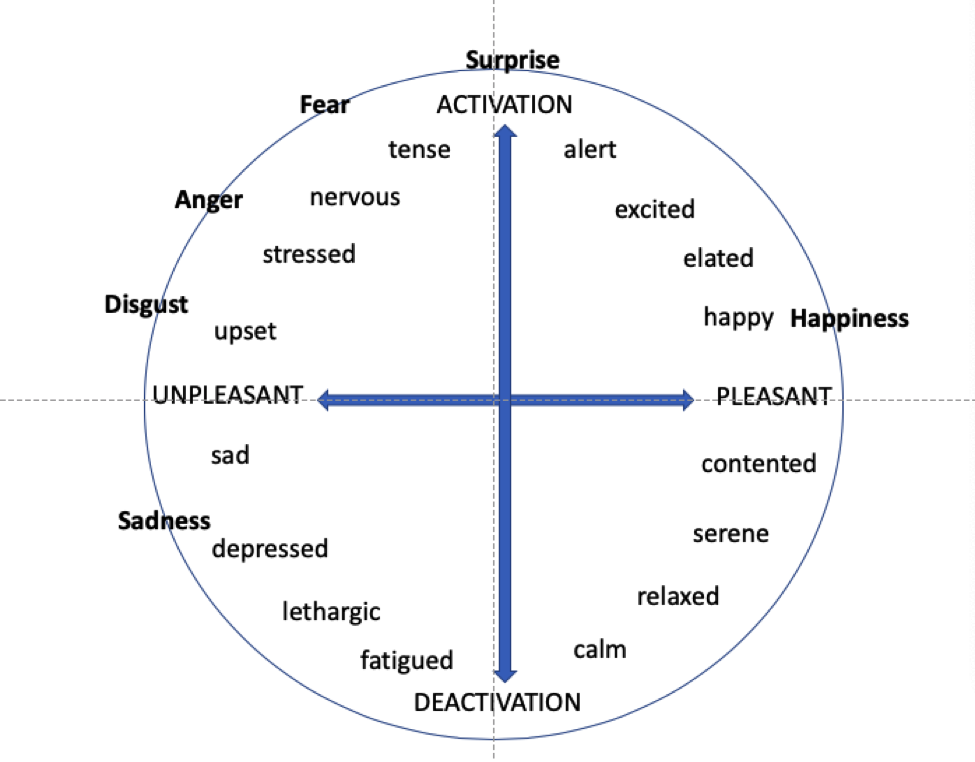

Researchers have also conceptualized emotions as varying along two axes (Russell & Barrett, 1999). This two-dimensional conceptualization of emotions is displayed in Figure 1 below. Any emotional experience was a certain combination of points or coordinates that varied along an X (valence) and Y (arousal) axis. Valence is whether something is positive (pleasant) or negative (unpleasant). Arousal refers to the level of intensity or activation in the body when we experience an emotion. In Figure 1, you can see that the emotion, surprise has the highest level of activation out of all of the emotions, while sadness has the lowest level of activation and is in the quadrant with other experiences that involve deactivation (e.g. depressed, lethargic, fatigued). So, for example anger would be considered a negative, unpleasant (valence) and higher (intensity/arousal level) activation level than sadness..

The inner circle represents the core affect or mood while the outer circle shows the typical emotion that is felt. The two dimensions are useful in order to further identify emotions from each other. For example, disgust, anger and fear are all unpleasant and mid to high range on the body’s activation. Similarly, happiness and surprise are separated by the level of activation and how pleasant the experience of the emotion is.

Figure 1: Emotions in the circumplex model (Barrett & Russell, 1988) vary on two dimensions

After thinking about the complexity of the process and experience of emotional expression, it makes sense that the structure of emotions is more complex than researchers once thought.

Structure of Emotions

Since emotions are subjective (Barrett et al., 2007), researchers rely on participants’ report of what emotions they are experiencing from certain triggers. Researchers have explored the structure of emotions and emotions are said to have “fuzzy boundaries” in that it is difficult to tell where one emotion starts and the other one ends (Fehr & Russell, 1984). It makes sense that there are fuzzy boundaries or gradients that slide into each emotion. People have a difficult time accurately identifying their own emotions, there are blends of emotions, and emotions with differing intensities. And according to that two-dimensional model of emotions in Figure 1, we see that what separates one emotion from another is the level of activation or deactivation and whether the experience is pleasant or more unpleasant. For example, if you see a small child being bullied outside of a department store and you are deciding how to intervene, is it anger, fear, or dread that you feel?

Level of activation can help us understand when you might be more likely to feel fear versus anger. You might label it anger if you experience the enough activation from the trigger (seeing the child being bullied) to result in a fight or flight response. The fight response would mean that you would probably approach the bully and intervene. If you experience an even higher level of activation, you might be actually experiencing fear. You might be more likely to flee or decide not to approach the bully.

The valence or degree to which we see the experience as pleasant or unpleasant can also shed some light on whether we are experiencing one emotion versus another. For example, think about the difference between when you experience sadness or experience fatigue. Feeling sad is more unpleasant than just feeling fatigue. Another difference between sad and fatigue is that when you experience fatigue you are even more deactivated than when you feel sad. Depressed is more unpleasant than fatigued and has a slightly higher level of activation than lethargic.

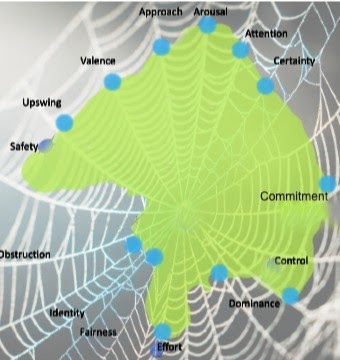

Now that we see how it is useful to examine the structure of emotions in order to tell one emotional experience from another, we will look at a study that aimed to further our understanding of every day emotional experiences. Researchers have recently categorized emotions into 27 emotions that are all interconnected (Cowen & Keltner, 2017) almost shaped like the outside points of a spider web

Figure 2: The experience of feeling nostalgic. Adapted from Cowen & Keltner (2017)

These emotions all vary in the amounts of 14 affects that participants said they experienced. These affect categories were Approach; arousal; attention; certainty; commitment; control; dominance; effort; fairness; identity; obstruction; safety; upswing; and valence. In figure 2 the experience of feeling nostalgic involves varying levels in the 14 affect categories. The yellow area shows the degree to which people experience each of the 14 affect categories when feeling nostalgic.

All this adds up to what can be described as one big spider web of possible emotions that we experience. Cowen & Keltner (2017) sought to gather data on individuals’ emotional experiences by combing the internet for more than 2120 videos clips averaging in five seconds in length that would all be likely to arouse emotion in viewers.

The clips showed evocative life events including births, sexual acts, death, vomit, feces, embarrassment, anger, sadness, anxiety, calmness, nostalgia, and many others. They used over 2100 people who watched 20-30 videos and self-reported their emotions.

Certain groups watched and rated 30 videos also along certain different gradients of emotion. Participants watched the random videos and described their emotional experiences during the videos. They also rated the emotional experience for the 14 affect categories: Approach; arousal; attention; certainty; commitment; control; dominance; effort; fairness; identity; obstruction; safety; upswing; and valence. When the study had finished the researchers had managed to gather data regarding emotional experiences on over 324,066 self-reported individual judgements of emotional experiences!

Three Views of Emotional Experience

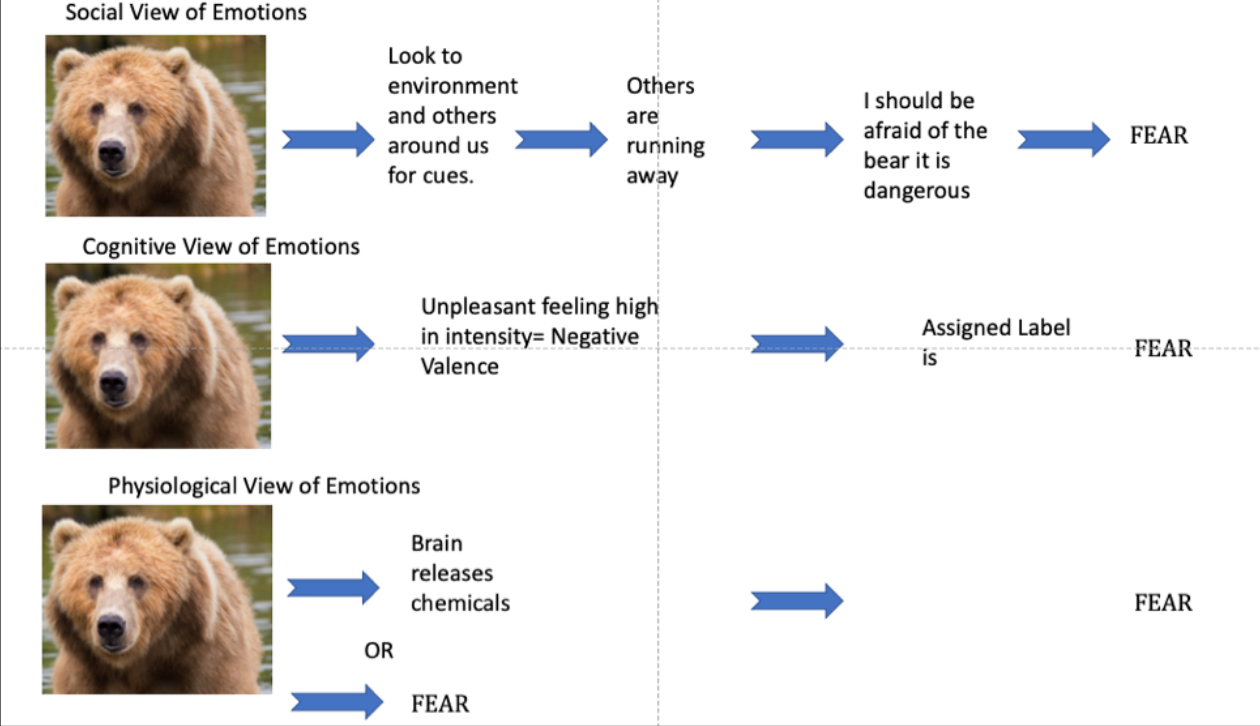

There are multiple theories of emotions, but we will focus on theories from three broad views. Each of these views conceptualizes emotional functionality in everyday life. These views are either physiological, cognitive, or social.

Physiological

Physiological views of emotions see the body’s reaction to stimuli as the emotion. 'A biological view of emotions believes certain neurotransmitters create different emotions. In other words, when a neuron crosses a synapse, this transmission makes up what we experience as an emotion. Different neurotransmitters create different emotional states. Critics of this approach argue that to only examine the neuron transmission is to miss the very human experience that are emotions. Most argue that emotions are not simply one component and that emotions involve the other components (i.e. chemical reactions, behaviors, processes, appraisals of events, and thoughts). However, each of the views presents their way of explaining emotions as the most accurate. What most modern emotion researchers can agree on is that emotions are multidimensional, influenced by our environment, involve physiological processes, and also that emotions depend on our perceptions and interpretations.

While we might use our verbal and nonverbal behaviors in order to express emotion, emotions are not simply behaviors. Anger is not simply pounding your steering wheel when you get cut off in traffic. Researchers who agree with this physiological perspective often argue that it is difficult to separate the reaction of the body to a stimulus from the experience of the emotion. For example, is any anger that we experience simply a state of the nervous system? Physiological views of emotions claim that when we experience the emotional trigger (seeing a grizzly bear charge toward us) we experience the emotion either simultaneously to the trigger or because of the trigger. In the physiological view, as we see the bear, we experience fear and that fear is the body’s reaction (increased heart rate, dilated pupils and adrenalin).

Other researchers in this view argue that the emotional response is a two-step process. First, we see the bear. Then the body responds to the trigger by communicating with the brain to release chemicals. The release of the chemicals causes the emotion. We know that our emotions are more than just neurological processes, (Barrett et al., 2007).

Let’s look at an example that illustrates the physiological view. A day-time talk show invited guests who were extremely afraid of clowns. Any type of clowns caused one guest to lock up with fear. What would be the most effective way to decrease the guest’s fear around clowns (trigger)? Instead of gradually exposing the guest to pictures of clowns, then movies about circuses, then trying on clown makeup, then finally interacting with a live clown, the talk show staff stranded the guest at a horror house of evil-looking clowns. Rather than ridding the guest of intense fear of clowns the event most likely increased the fear and caused even more trauma.

Instead of focusing on the cause-effect relationship other researchers focus their exploration on what people say their emotional experiences are like. These researchers believe people's reports of what they experience offer the best source of information. We feel something when we experience emotion and that feeling makes up a part of the structure of emotions. What do you think that talk show guest recalls of the experience in the horror house filled with people dressed as clowns?

We know that intense emotions cause changes in our bodies. For example, if someone accidentally hits their thumb with a hammer, they will probably yell out in pain and perhaps swear out loud. Their eyes might start watering, their pulse might increase and they might start to sweat. Are these physiological outcomes the same as the emotion? Some emotion theorists would explain the physiological outcomes occur because of the emotional experience. they are occurring because of the emotional experience of what we would characterize as the reaction to pain.

Anger is not the only emotion that can cause physiological outcomes. We can make ourselves sick with worry. Students who experience intense anxiety before public speaking, can feel weak, sweaty, faint, develop stomach issues, and have a racing pulse (Bodie, 2010). Grief is another intense emotion that causes changes in our bodies. Perhaps you receive some bad news, you may experience tunnel vision, lack of awareness of your surroundings, pressure in the chest, shortness of breath. When one is able to identify what changes in their body they are experiencing, it can help him/her to know how to deal with those emotions.

We also know that physiological changes can cause emotion. Increase in hormones such as oxytocin after having a baby results in an intense experience of love and warmth toward the infant (Scatliffe, 2019). When we lack a certain amount of hormone stored in the body, such as the necessary buildup of serotonin, we can experience depression.

Cognitive

Cognitive theorists believe that what we label an emotion depends on whether we assign a label of positive or negative to the trigger. So, two people could have the same trigger, let’s say they both sleep through the alarm going off in the morning in order to get to work. However, person A doesn’t worry or experience as much anxiety over this event as person B. Person A tends to assign a more neutral or even positive meaning to sleeping through the alarm because they get to have twenty more minutes of sleep. The person might look at the situation and think, “That was so worth it!” They might continue to reason that, “I’m just going to have to explain what happened and work another 30 minutes to make up for it. I’m in control of this situation.”

Person B wakes up with a start, you are confused. What did you forget? The alarm! Now you are going to be late, you think. Your pulse quickens, a sheen of sweat gathers at your neck. You are panicking. Therefore, even though the two people have the same trigger, the emotion experienced and the body’s reaction to the experience can be quite different. Why is this? A look at the social view of emotions may offer some answers.

Social

One reason that you may experience intense emotion when someone else doesn’t is that our perception of a trigger matters when we experience emotion. Indeed, it is difficult to discuss cognitive perspectives of emotions without mentioning the social environment. Verbal and nonverbal symbols communicate emotion. Averill (1980) argued that emotions are socially constructed and we give verbal and nonverbal cues as to what emotions we are experiencing and what emotions are appropriate for others to experience. Averill’s argument constitutes the social approach to emotions. When faced with an emotional situation, we look to those in our environment for visual cues.

For example, have you ever seen a little kid running and they fall and look around to see how people are reacting to them falling? They are using the expression of others to help determine whether they should produce tears or not. Their thoughts might go something like this: If it is a big deal, my parents will come running over and look concerned (visual cues) and therefore that episode of falling should hurt more. However, when a parent says something like, “nice save!”, or pretends that the child has just successfully slid into a base in baseball, “you’re safe!” then the child sees that his or her parents are okay with them falling, they will be more likely to not label the experience (falling) as negative. They may be less likely to produce some tears for their parents. Ultimately, they will be less likely to experience any pain from the fall. It is in this way that the child’s emotional experience is socially constructed and communicated through interaction with others. Later, we will see that our thoughts play a large role in forming emotions.

Figure 3: Three Approaches to Emotion

Summary

In this unit, we defined emotion and distinguished it from mood, or general disposition. We then saw how emotions are structured. Our emotions are complex and can be compared to the outside points of a spider web. Finally, we were introduced to the physiological, cognitive and social views of emotions.

Learning Activities

Class Activity 1: Discussion Questions

Ask your students the following questions below to spark a discussion about emotions:

- Have you ever been paralyzed with fear? How long did it take for the emotion to wear off? Did you tell yourself get away from the trigger? What worked best? So, how do you get someone to be less afraid of something?

- Can you recall having an emotional reaction to something going wrong? Did you have a more intense reaction than you thought you might? What was the trigger?

- How do you think you would feel if you tripped and fell while in an empty classroom? How about a room full of classmates?

Class Activity 2: Phone Selfie Activity

This activity gives your students a chance to use their most prized possession in class—their smart phone. After discussing the importance of identifying emotions in ourselves and in others have students break up into small groups and assign them a certain emotion. For example, you can use the basics seven emotions or you can have them try to tackle accuracy using a couple of the 27 emotional experiences that are explored in emotion research. Have students take selfies of their own faces attempting each one of the emotional displays. Then, have the partner look at the pictures on the phone and try to decode what each one of the emotions is. Have students talk about their guesses/interpretations of each selfie. If there is enough time, have a couple of groups share their photos that were the most difficult to decode.

Debrief: How accurate were you in decoding these emotions? What would help you to be more accurate?

References

Averill, J. R. (1980). A Constructivist view of emotion. In Plutchik, R., & Kellerman, H. (Eds.)., Theories of emotions (pp. 305-339). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2013-0-11313-X

Barrett, L. F., Mesquita, B., Ochsner, K. N., & Gross, J. J. (2007). The experience of emotion. Annual review of psychology, 58, 373–403.

Bodie G. D. (2010). A racing heart, rattling knees, and ruminative thoughts: Defining, explaining, and treating public speaking anxiety, Communication Education, 59, 70-105.

Cowen, A. S. & Keltner, D. (2017). Self-report captures 27 distinct categories of emotion bridged by continuous gradients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 114, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1702247114

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1986). A new pan-cultural expression of emotion. Motivation and Emotion, 10, 159-168.

Ekman, P. E., Sorenson, R., & Friesen, W. V. (1969). Pan-Cultural Elements in Facial Displays of Emotion. Science, 4, 86-88.

Gaines, J., & Jermier, J. (1983). Emotional exhaustion in a high stress organization. The Academy of Management Journal, 26(4), 567-586.

Fehr, B., & Russell, J. A. (1984). Concept of emotion viewed from a prototype perspective. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113(3), 464–486. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.113.3.464

Scatliffe, N., Casavant, S., Vittner,D., & Cong, X. (2019). Oxytocin and early parent-infant interactions: A systematic review, International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 6, 445-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2019.09.009.

Russell, James & Barrett, Lisa. (1999). Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: Dissecting the elephant. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 805-19.

Trampe, D., Quoidbach, J., & Taquet, M. (2015). Emotions in everyday life. PloS one, 10(12), e0145450. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145450

Glossary

Basic emotions: The physiological response and cognitive interpretation of internal or external triggers that result in seven universal facial expressions including joy/happiness; sadness; anger; disgust; contempt; surprise; and fear.

Emotion: A physiological response and cognitive interpretation of internal or external triggers.

Expression: Conveying one’s emotion through both verbal and nonverbal communication.

Mixed emotion: Experiencing two different and opposite emotions at the same time (e.g., joy and sadness).

Mood: General disposition or state of feeling of a person.

Intensity/arousal level: Characterizes whether an emotion is high (e.g., anger) or low (e.g., calmness).

Primary emotion: Emotions that are combined or blended to become a secondary emotion.

Secondary emotion: A blend of two or more primary emotions.

Valence: Indicating whether an emotional experience or emotion is perceived as negative or positive.

Media

Media Activity 1: Interactive Experiment

Check out the Interactive research site set up from Cowen & Keltner (2017) emotions study. The site provides access to the interactive map of all the videos that were used in the experiment. You are able to select a clip and then view the explanation of the structure of emotion that the participants experienced. For each of the videos there is a different figure similar to Figure 2 in the module. See if you can identify a clip for the following emotions: Joy, embarrassment, and love. How are the pictures of the 14 affect categories different?

Media Activity 2: "It's Not Your Fault"

Watch this famous clip from the movie, Good Will Hunting. Apply the three perspectives of emotions to this interaction. How do the characters experience emotion according to these perspectives? How does the therapist respond to them?

Here is the link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UYa6gbDcx18

Contributors and Attributions

This work is CC-BY-NC-SA Unless otherwise noted, "Communicating to Connect: Interpersonal Communication for Today" by the Department of Communication Studies at ACC is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Media Attributions

"Brown bear in body of water during day time" licensed by Pixabay is in the Public Domain, CC0.

"Spider Web in Close-Up Photography" licensed by Chase McBride is in the Public Domain, CC0.