4.3: Your Interpersonal Communication Preferences

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 74968

- JR Dingwall, Chuck Labrie, Trecia McLennon and Laura Underwood

- Olds College via eCampusOntario

Discover Your Preferences

Learning Objectives

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- describe each of the three domains of identity as they relate to communication practice,

- explain the relationship between identity and perception, and their influence on achieving shared understanding through communication,

- describe your own communication and work habit preferences, and

- explain how key factors of diversity influence your workplace behaviours.

This chapter is all about helping you to uncover your interpersonal communication preferences. When we study interpersonal communication, we often focus on external things like the audience or environment. Those things are important here as well, but they are important in the context of their impact on you.

The chapter begins with an overview of the three core elements that make up your identity. Personal identity elements are examined using the five-factor personality trait model, on which many personality tests are built. The second element is your social identity, which would include things like identifying socially as an animal rescue volunteer, an entrepreneur, or a marathon runner. The third is your cultural identity, which can include elements such as your race, ethnicity or gender.

The next section of the chapter takes a deeper look at other elements of your identity. Some elements of your identity are things you choose, known as avowed identity, and some are elements that are put upon you, known as ascribed identity.

The focus is then turned to perception, including how selective perception can often negatively affect interpersonal communication.

The chapter wraps up with information to help you determine your preferences and work habits, a review of communication channels, and a peek at Belbin’s nine team roles that may help you understand and excel at communicating interpersonally while doing team work.

Having a better knowledge of your own interpersonal communication preferences will allow you to better understand yourself, your identity, and motivations. This awareness is a useful first step in developing your abilities to relate with and understand other people too.

Personal, Social, and Cultural Identity

We develop a sense of who we are based on what is reflected back on us from other people. Our parents, friends, teachers, and the media contribute to shaping our identities. This process begins right after we are born, but most people in Western societies reach a stage in adolescence in which maturing cognitive abilities and increased social awareness lead them to begin to reflect on who they are. This begins a lifelong process of thinking about who we are now, who we were before, and who we will become (Tatum, 2009). Our identities make up an important part of our self-concept and can be broken down into three main categories: personal, social, and cultural identity.

Did you know?

IDENTITY was Dictionary.com’s word of the year for 2015!

Our identities are formed through processes that started before we were born and will continue after we are gone; therefore, our identities aren’t something we achieve or complete. Two related but distinct components of our identities are our personal and social identities (Spreckels and Kotthoff, 2009). Personal identities include the components of self that are primarily intrapersonal and connected to our life experiences. For example, I may consider myself a puzzle lover, and you may identify as a fan of hip-hop music. Our social identities are the components of self that are derived from involvement in social groups.

Example identity characteristics

| Personal | Social | Cultural |

|---|---|---|

| Antique Collector | Member of Historical Society | Irish Canadian |

| Dog Lover | Member of Humane Society | Male/Female |

| Cyclist | Fraternity/Sorority Member | Greek Canadian |

| Singer | High School Music Teacher | Multiracial |

| Shy | Book Club Member | Heterosexual |

| Athletic | Entrepreneurial Co-Working Member | Gay | Lesbian | Two Spirited |

Personal identities may change often as people have new experiences and develop new interests and hobbies. A current interest in online video games may later give way to an interest in graphic design. Social identities do not change as often, because they depend on our becoming interpersonally invested and, as such, take more time to develop. For example, if an interest in online video games leads someone to become a member of an online gaming community, that personal identity has led to a social identity that is now interpersonal and more entrenched.

Cultural identities are based on socially constructed categories that teach us a way of being and include expectations for social behaviour or ways of acting (Yep, 2002). Since we are often a part of them from birth, cultural identities are the least changeable of the three. The social expectations for behaviour within cultural identities do change over time, but what separates them from most social identities is their historical roots (CollIer, 1996). For example, think of how ways of being and acting have changed in America since the civil rights movement.

Common ways of being and acting within a cultural identity group are expressed through communication. In order to be accepted as a member of a cultural group, members must be acculturated, essentially learning and using a code that other group members will be able to recognize (Collier, 1996). We are acculturated into our various cultural identities in obvious and less obvious ways. We may literally have a parent or friend tell us what it means to be a man or a woman. We may also unconsciously consume messages from popular culture that offer representations of gender.

Personal Identity

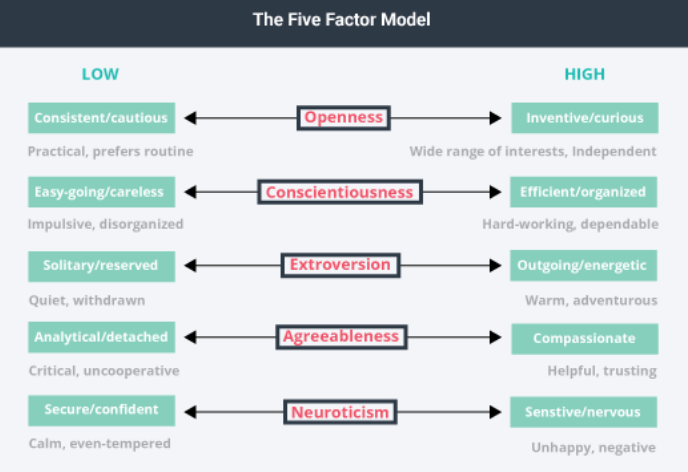

We will use the Five-Factor Model to examine your personal identity. You can use the acronym OCEAN to remember the five traits, which are Openness, Conscientiousness, Extroversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Take a look at the following scale. Where would you position yourself on the continuum for each of the traits?

Five-Factor Personality Model by L. Underwood Adapted from OpenStax CNX

These traits have a high degree of influence over your working life. They will help you to decide which career path is right for you; for example, if you identify as highly extroverted and conscientious with low neuroticism, you would do well in a sales-oriented position, but someone who identifies on the opposite ends of these scales is unlikely to enjoy or excel at this type of work.

Explore the Five Factors

Psychologist World provides quizzes to discover where you sit on each factor’s continuum.

These traits will dictate the people you collaborate with successfully, your team-working ability, and the type of environment you prefer to work in. Your position on the conscientiousness scale can help to predict your job performance (Hurtz & Donovan, 2000). For example, people who are highly conscientious are more able to work within teams and are less likely to be absent from work. These traits are also connected to leadership ability (Neubert, 2004). Although it may seem counterintuitive at first, if you score low on the agreeableness scale, you are more likely to be a good leader. If you consider the division between leaders and followers on a team, those who make decisions and voice their opinions when they do not agree are promoted to higher ranks, while those who are happy to go along with the consensus remain followers.

These traits will also influence your overall enjoyment of the workplace experience. For example, agreeableness and extroversion are indicators that you will enjoy a social workplace where the environment is set up to foster collaboration through an open office concept and lots of team-working. Conversely, if you score low on these two traits, that doesn’t mean that you will not be a good worker, just that you might not suit this type of environment. If you score low on these two traits but high on openness and conscientiousness, you might instead be an excellent entrepreneur or skilled in creative pursuits such as design or storytelling.

Social Identity

Your social identity gives a sense of who you are, based on your membership in social groups. Your social identity can also be connected to your cultural identity and ethnicity. For example, if you are nationalistic or have pride in belonging to a particular country or race, this is part of your social identity, as is your membership in religious groups. But your social identity can also result in discrimination or prejudice toward others if you perceive the other group as somehow inferior to your own. This can occur innocently enough, at first, for example, through your allegiance to a particular sports team. As part of your identity as a fan of this team, you might jokingly give fans of a rival team a hard time, but be cautious of instances where this could become derogatory or even dangerous. For example, if your fellow fans use an insensitive term for members of the rival group, this can cause insult and anger.

Cultural Identity

The identifiers that shape your cultural identity are conditions like location, gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, nationality, language, history, and religion. Your understanding of the normal behaviour for each of these cultures is shaped by your family and upbringing, your social environment, and the media. Perhaps unconsciously, you mirror these norms, or rebel against them, depending on your environment and the personal traits outlined above.

Your perception of the world, and the way you communicate this, is shaped by your cultural identity. For example, one of our authors had a white South African colleague who, in casual conversation, used a racial term to refer to black South Africans. While the author was affronted by the colleague’s use of the term, the author came to realize that this word choice had been a result of the colleague’s upbringing. The colleague’s parents, friends, and community had been using that term casually; as such, using that racial term in everyday speech was an ingrained behaviour that did not hold the level of offense for him that it did for the community that he was referring to. While the term has always been considered an ethnic slur, white Afrikaans-speaking people used it as a casual term to reinforce their perceived superiority during the country’s history, particularly during apartheid. While offensive to those outside of his cultural and social group, the term was used within it habitually.

Depending on your environment, you may feel societal pressure to conform to certain cultural norms. For example, historically, immigrants to English-speaking countries adopted anglicized names so that their names would be easier to pronounce and so that they could more easily fit into the new culture. For example, Giovanni may have been renamed John (as was the case with Giovanni Caboto, the Italian explorer, more widely known as John Cabot). However, consider how important your own name is to your identity. For many of us, our names are a central piece of who we are. Thus, in changing their names, these people ended up changing an integral element of their self-perception.

The cultural constructs of gender and power often play a part in workplace communication, as certain behaviours become ingrained. For example, in Canada and the United States, male leaders are typically applauded and thought of as forward-thinking when they adopt typically “feminine” traits like collaboration and caring. Those same traits in female leaders are often considered weak or wishy-washy. Similarly, women who are competitive or assertive are “female dogs” to be put down, whereas men exhibiting these traits are seen as self-starters or go-getters. It is difficult to be a female leader and be socially beyond reproach in the West.

Most of us are often totally unaware of how we enforce or reinforce these norms that prevent women from reaching their full potential in the workplace. Not to mention the implications on how a female leader might communicate effectively interpersonally. In some authoritarian cultures, it is considered inappropriate for subordinates to make eye contact with their superiors, as this would be disrespectful and impolite. In some other cultures, women are discouraged from making too much eye contact with men, as this could be misconstrued as romantic interest. These behaviours and interpretations may be involuntary for people who grew up as part of these cultures.

Ascribed and Avowed Identity

Any of these identity types can be ascribed or avowed. Ascribed identities are personal, social, or cultural identities that others place on us, while avowed identities are those that we claim for ourselves (Martin and Nakayama, 2010). Sometimes people ascribe an identity to someone else based on stereotypes. If you encounter a person who likes to read science-fiction books, watches documentaries, wears glasses, and collects Star Trek memorabilia, you may label him or her a nerd. But if the person doesn’t avow that identity, using that label can create friction and may even hurt the other person’s feelings. However, ascribed and avowed identities can match up. To extend the previous example, there has been a movement in recent years to reclaim the label nerd and turn it into something positive, and hence, a nerd subculture has been growing in popularity. For example, MC Frontalot, a leader in the nerdcore hip-hop movement, says that being branded a nerd in school was terrible, but now he raps about “nerdy” things like blogs to sold-out crowds (Shipman, 2007). We can see from this example that our ascribed and avowed identities change over the course of our lives. Sometimes they match up, and sometimes they do not, but our personal, social, and cultural identities are key influencers on our perceptions of the world.

Perception

Perception is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information to represent and understand the environment. The selection, organization, and interpretation of perceptions can differ among people. When people react differently to the same situation, part of their behavior can be explained by examining how their perceptions are leading to their responses.

For example, how do you perceive the images below? What do you see? Ask a friend what they see in the images. Are your perceptions different?

Query

Naturally, our perception is about much more than simply how we see images. We perceive actions, behaviours, symbols, words, and ideas differently, too!

Selective Perception

Selective perception is driven by internal and external factors.

The following are some internal factors:

- Personality: Personality traits influence how a person selects perceptions. For instance, conscientious people tend to select details and external stimuli to a greater degree.

- Motivation: People will select perceptions according to what they need in the moment. They will favour selections they think will help them with their current needs and be more likely to ignore what is irrelevant to their needs. For example, a manager may perceive staying under budget as the top factor when ordering safety gear but miss or ignore the need for high quality.

- Experience: The patterns of occurrences or associations one has learned in the past affect current perceptions. For example, if you previously learned to associate men in business suits with clean-shaven faces or no discernable facial hair as ideal and trustworthy, you may dismiss the same man who shows up with a beard or moustache, perceiving he may have something to hide. Such a person will select perceptions in a way that fits with what they found in the past.

When you recognize the internal factors that affect perception selection, you also realize that all of these are subject to change. You can change or modify your personality, motivation, or experience. Being aware of this is helpful in interpersonal communication because we can use our perceptions as a catalyst for changing what we pay attention to (personality) in order to communicate better (motivation). Once we modify those, we can open ourselves to new patterns (experiences) and ways of understanding.

The following are some external factors of selective perception:

- Size: A larger size makes selection of an object more likely.

- Intensity: Greater intensity, in brightness, for example, also increases perceptual selection.

- Contrast: When a perception stands out clearly against a background, the likelihood of selection is greater.

- Motion: A moving perception is more likely to be selected.

- Repetition: Repetition increases perceptual selection.

- Novelty and familiarity: Both of these increase selection. When a perception is new, it stands out in a person’s experience. When it is familiar, it is likely to be selected because of this familiarity.

External factors can be designed in such a way as to affect your perception. Marketers, advertisers, and politicians are extremely well-versed in using external factors to influence perceptual selection. Let’s say you have a long cylinder of ice water in a beautiful glass container next to a short bowl of water in a plain, white ceramic container. Most people would choose the glass container because it looks bigger and the clarity may make it seem brighter, despite the fact that it contains less water than the bowl. Similarly, you may perceive that brand A is better than brand B because you’ve seen brand A in high-fashion magazines, while brand B is mostly available at discount stores in your local mall. You may pay more for brand A because you perceive you’re getting quality when in actuality brands A and B are made from the same material at the same low-cost overseas factory.

Perception can influence how a person views any given situation or occurrence, so by taking other people’s perceptions into account, we can develop insight into how to communicate more effectively with them. Similarly, by understanding more about our own perceptions, we begin to realize that there is more than one way to see something and that it is possible to have have an incorrect or inaccurate perception about a person or group, which would hinder our ability to communicate effectively with them.

Examine the vignette below and determine which of the three types of internal selective perception most closely matches this situation:

Culture and Perception

The author has taken two trips to the United Arab Emirates (UAE), landing at Dubai Airport. At the time of her visit, a visa was required for Canadians, and, as part of the visa requirements, travellers needed to be digitally fingerprinted and have an eye scan.

During her first trip there was no lineup. She went and was scanned and printed with no issues. On her second trip, she went to the familiar area, but there were two long lines nearly equal in length. There were no signs to indicate which line was designated for what, so she didn’t know which line to stand in or what the respective lines were for.

She looked around and saw some official-looking gentlemen at a nearby booth. She went and said, “Excuse me, sorry to bother you, but I need to have my visa sorted out and I don’t know which line I’m supposed to stand in.”

The men looked at her, staring daggers at her. She was perplexed, as they looked somehow angry or ticked off. After a long, uncomfortable silence, one of the men piped up and said, “You can stand in any line you want, ma’am.”

She felt frustrated that they seemed to be so unhelpful. She was mindful of her anger rising, tried to soften her tone, and said, “I’m not being funny here, but the last time I was here, there was no line. Now there are two, and I don’t know what they’re for because there are no signs, and so I don’t know which line I’m supposed to be in. This is why I came here to ask for your help, so I can know which line to stand in.”

Finally, the other man said, “Ma’am you can stand in that line there,” pointing to the line that happened to be closest to her.

“Thank you,” she said, walking away shaking her head. She was in line and still trying to figure out why those men at the booth had been so cross at her for asking a simple question. It made no sense.

She started looking at the people in her line. They seemed to come from a range of countries, and all looked travel worn. She looked at the other line. Same thing. She wondered, still, why there were two lines.

After doing some shuffling with her bags and passport, about 10 minutes after first standing in line, she had a huge realization. All the people in her line were women or children. All the people in the other line were men.

It took her over 10 minutes and an uncomfortable conversation to realize that in many Islamic countries, men and women mostly go about their day-to-day lives in separate ways. Her co-ed upbringing had completely blinded her to this reality in this context.

If it were a queue for a washroom, she would have noticed right away, but as a queue for a travel visa, it had genuinely not occurred to her—even after looking at these lines pretty intensely for several minutes—that the reason behind having two lines was that one was for men and the other for women and children.

Suddenly, she also understood that the two gentlemen at the booth had looked at her angrily because they might have thought she either was trying to make a point as a smug westerner or was totally dense. She laughed and laughed…

Perceiving Emotion

Part of perception in a communication context is about how we perceive another person’s mood, needs, and emotional state. We don’t always say what we really mean; therefore, some reading between the lines occurs when we are communicating with someone, particularly if their reaction is not what we expect.

For example, when a baby is crying, we, as adults, wonder, Has the baby eaten? Could the baby be tired? Is she uncomfortable or unwell? Has he been startled? Our first thoughts go to meeting the baby’s basic needs. Conversely, when we have an encounter with an adult who reacts to us with a negative emotion, we often think, This person is mad at me, He doesn’t like me, She’s not a nice person, or She’s in a bad mood for no reason. We take the adult’s response personally, but yet we know instinctively that the baby’s reaction is not about us. Why is it that we react so differently to the baby’s behaviour in contrast to the adult’s, even though the trigger may be very similar? We make assumptions based on our own perception, but we are not always right. If we, instead, considered whether or not the adult’s basic needs had been met, relationships and emotions in the workplace could be managed more easily. The next time you have a disagreement with someone, consider whether or not their essential needs are currently being met, and you may find that the lack of fulfillment of these needs—not something you have said or done—is playing a part in the person’s emotional response.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs from Simply Psychology

Psychologist Abraham Maslow (Maslow, 1943) described a series of need levels that humans experience. As Figure 4.2.3 shows, the more basic needs are at the bottom of the pyramid. The most basic needs must be met before humans will desire and focus their attention on the next level of the hierarchy. This plays a big part in communication—and miscommunication—with other people.

Let’s take a look at each of these needs, beginning with the most basic:

- Physiological: These are the physical needs required for survival, including air, water, food, clothing, and shelter. Without these, the body cannot function.

- Safety: These needs are required for humans to feel secure, and include physical safety, health, and financial security.

- Love and belonging: These are our social needs and include family, friendship, love, and intimacy.

- Esteem: These are our needs to feel respected by others and to have self-respect. This level of needs explains why we study, take up occupations, volunteer, or strive to increase our social status.

- Self-actualization: This refers to our desire to fulfill our potential. Each person will approach this need in their own way. For example, you might aim to become achieve athletic goals, while your friend may work at developing her artistic skill.

Think about how your basic needs are met in your workplace environment. Do you respond to others differently, or have trouble regulating emotion and mood when your basic needs are not met? This can, unknowingly for some, be the source of conflict, frustration, and misunderstanding between colleagues.

In a professional context, Maslow’s hierarchy is key to employee motivation, happiness, and productivity. We work to earn money so that our basic needs will be met. But some organizations extend their reach to further meet employee needs, for example, by providing food, social gatherings, professional development opportunities, career progression, and so on. These provisions make the organization more appealing to new applicants and encourages existing staff to stay with the company.

Preferences and Work Habits

The personality indicators described above have a significant impact on your working style and preferences. Your previous work experience, demographics, and strengths will also play a part. You may not have spent much time considering your own preferences and habits, or the impact of these on the people you work with. So, let’s take a few moments to look at this.

Ask yourself:

- Do you enjoy working in a sociable environment, or do you prefer to work in a more solitary environment?

- Do you feel more energized through meeting people and building relationships or from coming up with great ideas?

- Are you a big-picture person, or do you focus on the fine details?

- Is your decision-making process based more on logic or on feelings?

- At what time of day do you feel most productive?

- What practices help you stay organized?

- Do you prefer to take a planned, orderly approach to your work, or a more flexible and spontaneous approach?

- Which of your previous working environments did you find most enjoyable? Why?

- Which communication channels do you use, most commonly?

- What have previous colleagues and managers said about your skills and working process? Which elements have come up in performance reviews as things you excel at? What have you struggled with in the past?

- What are the demographics and traits of people you have worked best with in the past? With whom have you had conflicts and misunderstandings, and what do you think were the causes of these?

Channels of Communication

Do you recall the communication channels we discussed in the Foundations module? These have an impact on the way your message is received in any type of communication but are particularly important when you are communicating interpersonally. Your communication preferences are part of your interpersonal style, but when deciding which channel to use to communicate information to others, you will need to consider which channel is best for the situation.

For example, perhaps you are a millennial who prefers to communicate on-the-go using mobile devices and quick-response channels like text, social media, or instant message. But you might struggle to use these channels efficiently if your colleagues are primarily from the baby boomer generation, because your preferences might not align.

You may recall the term communication richness, first discussed in the Foundations module. The channels considered to be the most rich are those that transmit the most non-verbal information, such as, for example, face-to-face conversations or video conferencing. Channels that communicate verbal information, such as phone calls, for example, are less rich. The least rich channels use written communication, such as email or postal mail. Depending on the details of your message, you will identify the most effective channel to use. For example, if you need a response right away, if you anticipate an emotional response, or if your message needs to remain in strict confidence, you will need to use a highly information-rich channel. If your message is not urgent, intended for information only, and directed to a large group of people, you might choose a less rich channel. For a refresher on this concept, review the Choosing a Communications Channel Chapter of the Foundations module.

Team Roles

Belbin’s (1981) team inventory is a model that helps people to identify what strengths and weaknesses they can bring to a group or team. Normally, people fill out a questionnaire that helps determine what their top three team strengths are out of nine possible categories. According to Belbin’s research, these categories are stable across cultures. The nine categories are listed in the chart below:

| Action-Oriented Roles | Shaper | Implementer | Completer | Finisher |

| People-Oriented Roles | Coordinator | Team Worker | Resource Investigator |

| Thinking-Oriented Roles | Plant | Monitor-Evaluator | Specialist |

Research Break

- Find definitions or profiles for each for the nine team roles.

- Add the definitions or profiles to the Padlet below.

- Reflect on the following questions and add to Padlet as appropriate:

- Which top three roles do you think you align most with?

- Do you have a mix of action, people, and thinking-oriented roles, or do your team strengths fall in one or two of those categories?

- Have you worked with others who seem to clearly match one or more of the definitions you’ve uncovered?

Query

How you behave on a team and what strengths come to the surface usually depends on who else is on the team at least as much as your own personality traits and strengths. But because Belbin’s team roles look at your top three strengths, you can usually find a role on a team that plays to your strengths and have others take the lead in areas where you either are weaker or have little interest.

These team roles are another aspect of a diversity that allows and encourages people to bring their strengths and experiences to the table to solve problems or innovate. Having this framework helps increase the likelihood of interpersonal communication and team synergy because team members understand one another’s strengths and weaknesses and can determine their preferred team role(s).

Key Takeaways

In this chapter you learned about your own preferences and tendencies for communicating interpersonally as a foundation for understanding yourself and others better.

You examined several elements that make up your identity: these are the personal, social, and cultural aspects as well as ascribed and avowed identity.

Learning about perception and selective perception helped you to understand that there is more than one way to see something and that we sometimes choose to see only what we want to see. You learned that incorrect or inaccurate perception can get in the way of effective interpersonal communication.

Finally, you examined your work preferences and habits, reviewed your preferred communication channels, and researched where you might best lend your talent and experience to a team using Belbin’s Team Role framework.

This better understanding of your interpersonal communication preferences is the grounding you should find useful in the next chapter on cross-cultural communication.

Learning highlights

- Your identity consists of three main elements: personal, social, and cultural.

- An easy way to remember the five-factor personality model is by using the acronym OCEAN (openness, conscientiousness, extroversion | introversion, agreeableness, neuroticism).

- Ascribed identity is given to you, while avowed identity is what you choose for yourself.

- Perception is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information to represent and understand the environment.

- Belbin’s team inventory is a nine-category model that helps people to identify the top three categoric strengths they can bring to a group or team.

Further Reading, Links, and Attribution

Further Reading and Links

- BBC Future article on optical illusions – How your Eyes Trick Your Mind

References

Belbin, M. (1981). Management Teams. London; Heinemann.

Collier, M. J. (1996). Communication competence problematics in ethnic friendships. Communications Monographs, 63(4), 314–336.

Hurtz, G. M., & Donovan, J. J. (2000). Personality and job performance: The Big Five revisited. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 869–879.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological review, 50(4), 370.

Martin, J. N., & Nakayama, T. K. (2010). Intercultural communication in contexts.

Neubert, S. (2004). The Five-Factor Model of Personality in the Workplace. Retrieved from http://www.personalityresearch.org/papers/neubert.html.

Shipman, T. (2007, July 22). Nerds Get Their Revenge as at Last It’s Hip to Be Square. The Telegraph. Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/1558191/Nerds-get-revenge-now-its-hip-to-be-square.html.

Spreckels, J., and Kotthoff, H. (2009). Communicating Identity in Intercultural Communication. In Kotthoff, H., and Spencer-Oatey, H. (Eds.), Handbook of Intercultural Communication. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Tatum, B. D. (2000). The complexity of identity: Who am I. Readings for diversity and social justice, 9–14.

Yep, G. (2002). My Three Cultures: Navigating the Multicultural Identity Landscape. In Martin, J., Flores, L., and Nakayama, T. (Eds.), Intercultural Communication: Experiences and Contexts Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Attribution Statement (Your Interpersonal Communication Style)

This chapter is a remix containing content from a variety of sources published under a variety of open licenses, including the following:

Chapter Content

- Original content contributed by the Olds College OER Development Team, of Olds College to Professional Communications Open Curriculum under a CC-BY 4.0 license

- Content created by Anonymous for Foundations of Culture and Identity; in A Primer on Communication Studies, previously shared at http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/a-primer-on-communication-studies/s08-01-foundations-of-culture-and-ide.html under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license

- Content originally created by Boundless for The Perceptual Process; in Boundless Management published at www.boundless.com/management/textbooks/boundless-management-textbook/organizational-behavior-5/individual-perceptions-and-behavior-41/the-perceptual-process-217-3560/ under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license

- Figure X.X, Multistability by Alan De Smet published at https://en.Wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Multistability.svg&page=1 in the public domain

- The Five Factor Model, adapted from: © Dec 9, 2014 OpenStax Psychology, originally published at http://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@4.100:Vqapzwst@2/Trait-Theorists. Textbook content produced by OpenStax Psychology is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license.

Check Your Understandings

- Original assessment items contributed by the Olds College OER Development Team, of Olds College to Professional Communications Open Curriculum under a CC-BY 4.0 license