Introduction

Think of your memory as a vast, overgrown jungle. This memory jungle is thick with wild plants, exotic shrubs, twisted trees, and creeping vines. It spreads over thousands of square miles— dense, tangled, forbidding.

Imagine that the jungle is encompassed on all sides by towering mountains. There is only one entrance to the jungle, a small meadow that is reached by a narrow pass through the mountains.

In the jungle, there are animals—millions of them. The animals represent all of the information in your memory. Imagine that every thought, mental picture, or perception you ever had is represented by an animal in this jungle. Every single event ever perceived by any of your five senses—sight, touch, hearing, smell, or taste—is a thought animal that has also passed through the meadow and entered the jungle. Some of the thought animals, such as the color of your seventh-grade teacher’s favorite sweater, are well hidden. Other thoughts, such as your cell phone number or the position of the reverse gear in your car, are easier to find.

The memory jungle has two rules: Each thought animal must pass through the meadow at the entrance to the jungle. And once an animal enters the jungle, it never leaves.

The meadow represents short-term memory. You use this kind of memory when you look up a telephone number and hold it in your memory long enough to make a call. Short-term memory appears to have a limited capacity (the meadow is small) and disappears fast (animals pass through the meadow quickly).

The jungle itself represents long-term memory. This kind of memory allows you to recall information from day to day, week to week, and year to year. Remember that thought animals never leave the long-term memory jungle.

Memory Techniques: Organize It

Experiment with these techniques to develop a flexible, custom-made memory system that fits your style of learning. The techniques discussed here are divided into four categories, each of which represents a general principle for improving memory:

- Organize it. Organized information is easier to find.

- Use your body. Learning is an active process; get all of your senses involved.

- Use your brain. Work with your memory, not against it.

- Recall it. Regularly retrieve and apply key information.

Organize It

Be selective. There’s a difference between gaining understanding and drowning in information. During your stay in higher education, you will be exposed to thousands of facts and ideas. As you dig into your textbooks and notes, make choices about what is most important to learn. Imagine that you are going to create a test on the material. Next, consider the questions you would ask.

When reading, look for chapter previews, summaries, and review questions. Pay attention to anything printed in bold type. Also notice visual elements—tables, charts, graphs, and illustrations. They are all clues pointing to what’s important. During lectures, notice what the instructor emphasizes. Anything that’s presented visually—on the board, in overheads, or with slides—is probably key.

Make it meaningful. You remember things better if they have meaning for you. One way to create meaning is to learn from the general to the specific. Before you begin your next reading assignment, skim the passage to locate the main ideas. If you’re ever lost, step back and look at the big picture. The details then might make more sense.

Also, organize any list of items—even random items—in a meaningful way to make them easier to remember. Although there are probably an infinite number of facts, there are only a finite number of ways to organize them.

- By category. Organize any group of items by category. You can apply this suggestion to long to-do lists. For example, write each item on a separate index card. Create a pile of cards for calls to make, errands to run, and household chores to complete. These will become your working categories. The same concept applies to the content of your courses. In chemistry, a common example of organizing by category is the periodic table of chemical elements. When reading a novel for a literature course, you can organize your notes in categories such as theme, setting, and plot. Then, take any of these categories and divide them into subcategories such as major events and minor events in the story. Use index cards to describe each event.

- By chronological order. Any time you create a numbered list of ideas, events, or steps, you are organizing by chronological order. To remember the events that led up to the US stock market crash of 1929, for instance, create a timeline. List the key events on index cards. Then, arrange the cards by the date of each event.

- By spatial order. In plain English, this means making a map. When studying for a history exam, for example, you can create a rough map of the major locations where events take place.

- By alphabetical order. This old standby for organizing lists is simple, and it works.

Create associations. The data already encoded in your neural networks are arranged according to a scheme that makes sense to you. When you introduce new data, you can remember them more effectively if you associate them with similar or related data.

Think about your favorite courses. They probably relate to subjects that you already know something about. If you have been interested in politics over the last few years, you’ll find it easier to remember the facts in a modern history course. Even when you’re tackling a new subject, you can build a mental store of basic background information—the raw material for creating associations. Preview reading assignments, and complete those readings before you attend lectures. Before taking upper-level courses, master the prerequisites.

Memory Techniques—Use Your Body

Because learning is an active process, you should get all of your senses involved. When you use your senses, you process the information at a deeper level and you are more likely to remember it. For example, imagine you are trying to learn the scientific method, you might see a visual of the steps in the process, listen to a video explaining it, and maybe even conduct your own experiment to try it out. You can use some of the following memory techniques that focus on using all of your senses.

Learn actively. Action is a great memory enhancer. Test this theory by studying your assignments with the same energy that you bring to the dance floor or the basketball court.

You can use simple, direct methods to infuse your learning with action. When you sit at your desk, sit up straight. Sit on the edge of your chair as if you were about to spring out of it and sprint across the room.

Experiment with standing up when you study. It’s harder to fall asleep in this position. Some people insist that their brains work better when they stand. Pace back and forth and gesture as you recite material out loud. Get your body moving.

Relax. When you’re relaxed, you absorb new information quickly and recall it with greater ease and accuracy. Students who can’t recall information under the stress of a final exam can often recite the same facts later when they are relaxed.

Relaxing might seem to contradict the idea of active learning, but it doesn’t. Being relaxed is not the same as being drowsy, zoned out, or asleep. Relaxation is a state of alertness, free of tension, during which your mind can play with new information, roll it around, create associations with it, and apply many of the other memory techniques. You can be active and relaxed.

Recite and repeat. When you repeat something out loud, you anchor the concept in two different senses. First, you get the physical sensation in your throat, tongue, and lips when voicing the concept. Second, you hear it. The combined result is synergistic, just as it is when you create pictures. That is, the effect of using two different senses is greater than the sum of their individual effects.

The out loud part is important. Reciting silently in your head can be useful—in the library, for example—but it is not as effective as making noise. Your mind can trick itself into thinking it knows something when it doesn’t. Your ears are harder to fool.

The repetition part is important, too. Repetition is a common memory device because it works. Also remember that recitation works best when you recite concepts in your own words.

Write it down. The technique of writing things down is obvious, yet easy to forget. Writing a note to yourself helps you remember an idea, even if you never look at the note again. Writing notes in the margins of your textbooks can help you remember what you read.

You can extend this technique by writing down an idea not just once, but many times. When you choose to remember something, repetitive writing is a powerful tool.

Create pictures. Draw diagrams. Make cartoons. Use these images to connect facts and illustrate relationships. You can see and recall associations within and among abstract concepts more easily when you visualize both the concepts and the associations. The key is to use your imagination. Creating pictures reinforces visual and kinesthetic learning styles.

For example, Boyle’s law states that, at a constant temperature, the volume of a confined ideal gas varies inversely with its pressure. Simply put, cutting the volume in half doubles the pressure. To remember this concept, you might picture someone doubled over, using a bicycle pump. As she increases the pressure in the pump by decreasing the volume in the pump cylinder, she seems to be getting angrier. By the time she has doubled the pressure (and halved the volume), she is boiling (Boyle-ing) mad.

Memory Techniques—Using Graphic Organizers

You can also create pictures as you study by using graphic organizers. These preformatted charts prompt you to visualize relationships among facts and ideas.

One example is a topic-point-details chart. At the top of this chart, write the main topic of a lecture or reading assignment. In the left column, list the main points you want to remember. In the right column, list key details related to each point.

Topic-Point-Details Chart

|

Memory Techniques

|

|

Point

|

Details

|

|

1. Be selective

|

Choose what not to remember.

|

|

2. Make it

|

Organize by time, location, category,

|

|

3. Create

|

Link new facts with facts you already know.

|

|

4. Learn actively

|

Sit straight.

|

|

5. Relax

|

Release tension.

|

You could use a similar chart to prompt critical thinking about an issue. Express that issue as a question, and write it at the top. In the left column, note the opinion about the issue. In the right column, list notable facts, expert opinions, reasons, and examples that support each opinion. The example question-opinion-support chart is about tax cuts as a strategy for stimulating the economy.

Question-Opinion-Support Chart

|

Stimulate the Economy with Tax Cuts?

|

|

Opinion

|

Support

|

|

Yes

|

Savings from tax cuts allow businesses to invest

|

|

No

|

Years of tax cuts under the Bush administration failed

|

|

Maybe

|

Tax cuts might work in some economic conditions.

|

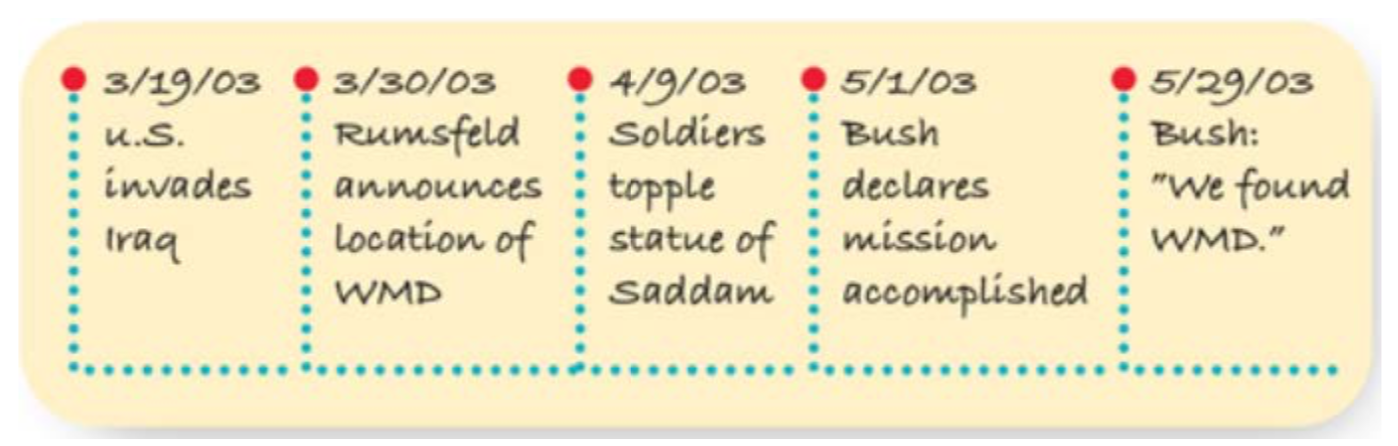

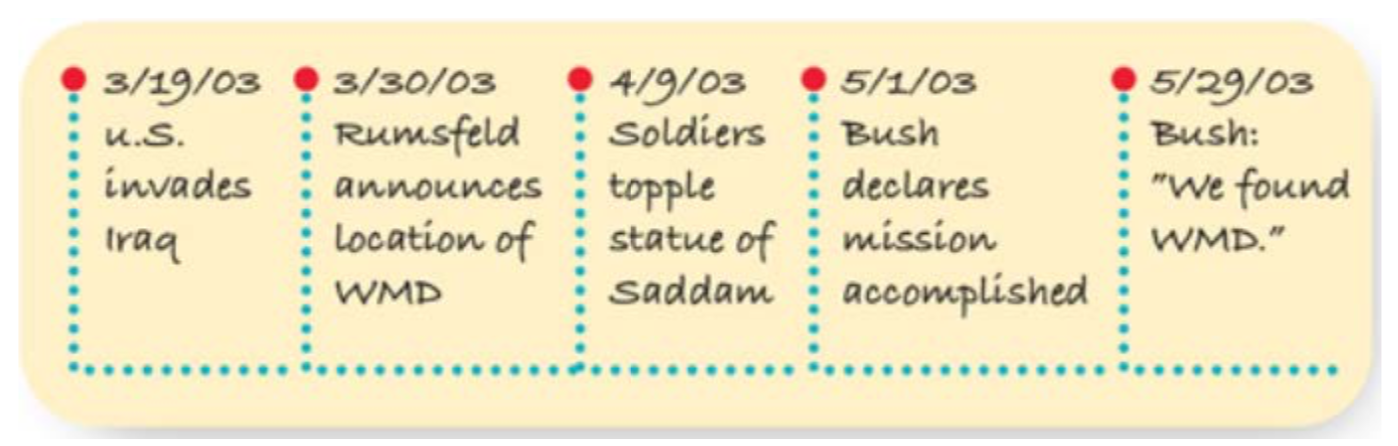

Sometimes, you’ll want to remember the main actions in a story or historical event. Create a timeline by drawing a straight line. Place points in order on that line to represent key events. Place earlier events toward the left end of the line and later events toward the right. The example timeline shows the start of time line of events relating the US war with Iraq.

Timeline

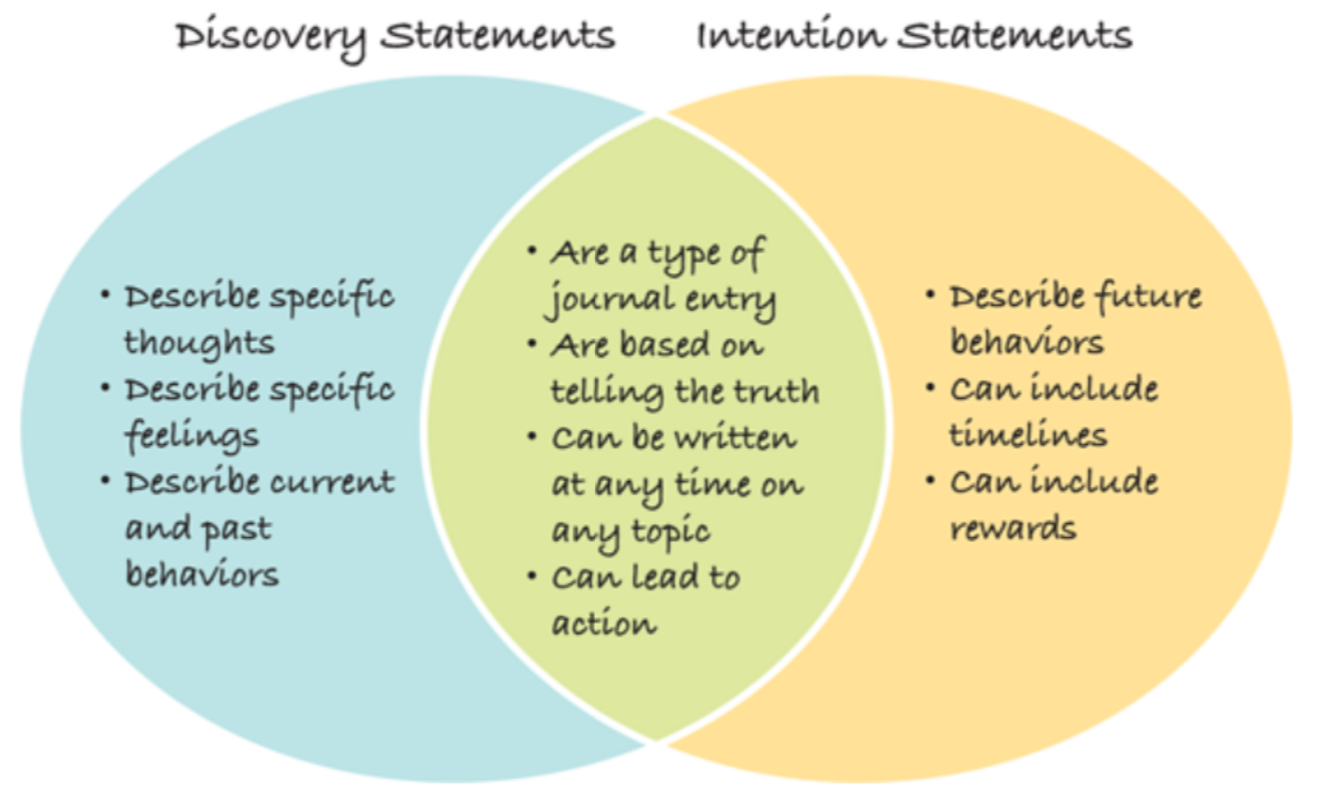

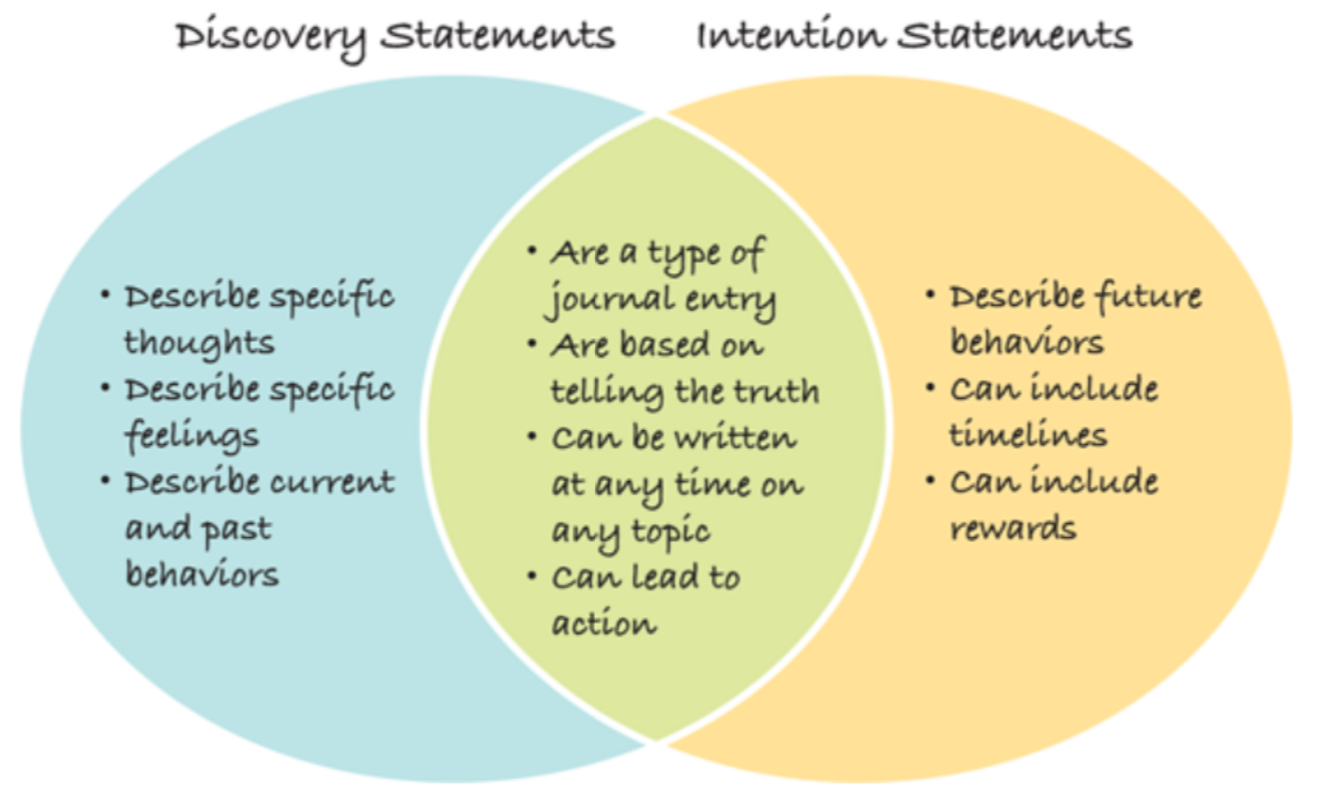

When you want to compare or contrast two things, play with a Venn diagram. Represent each thing as a circle. Draw the circles so that they overlap. In the overlapping area, list characteristics that the two things share. In the outer parts of each circle, list the unique characteristics of each thing. The example Venn Diagram compares the two types of journal entries included in this course—Discovery Statements and Intention Statements.

Venn Diagram

The graphic organizers described here are just a few of the many kinds available. To find more examples, do an Internet search. Have fun, and invent graphic organizers of your own.

Memory Techniques—Use Your Brain, Part 1

In addition to organizing your information and using your body, using your brain is a memory technique. Using your brain effectively involves understanding how your brain works so that you can optimize your study time and strategies to learn more efficiently.

Try some of the following strategies to engage your memory by using your brain:

Engage your emotions. One powerful way to enhance your memory is to make friends with your amygdala. This area of your brain lights up with extra neural activity each time you feel a strong emotion. When a topic excites love, laughter, or fear, the amygdala sends a flurry of chemical messages that say, in effect, This information is important and useful. Don’t forget it.

You’re more likely to remember course material when you relate it to a goal—whether academic, personal, or career—that you feel strongly about. This is one reason why it pays to be specific about what you want. The more goals you have and the more clearly they are defined, the more channels you create for incoming information.

Overlearn. One way to fight mental fuzziness is to learn more than you need to know about a subject simply to pass a test. You can pick a subject apart, examine it, add to it, and go over it until it becomes second nature.

This technique is especially effective for problem solving. Do the assigned problems and then do more problems. Find another textbook and work similar problems. Make up your own problems and solve them. When you pretest yourself in this way, the potential rewards are speed, accuracy, and greater confidence at exam time. Being well prepared can help you prevent test anxiety.

Escape the short-term memory trap. Short-term memory is different from the kind of memory you’ll need during exam week. For example, most of us can look at an unfamiliar seven-digit phone number once and remember it long enough to dial it. See whether you can recall that number the next day.

Short-term memory can fade after a few minutes, and it rarely lasts more than several hours. A short review within minutes or hours of a study session can move material from short-term memory into long-term memory. That quick mini-review can save you hours of study time when exams roll around.

Use your times of peak energy. Study your most difficult subjects during the times when your energy peaks. Some people can concentrate more effectively during daylight hours. Observe the peaks and valleys in your energy flow during the day, and adjust study times accordingly.

Memory Techniques—Use Your Brain, Part 2

Using your brain effectively also involves planning your study time and being aware of your attitudes and intentions toward learning. Following are some additional strategies for engaging your memory to help you more effectively learn the task at hand.

Try each of these strategies, and see which method works best or you:

Distribute learning. As an alternative to marathon study sessions, experiment with several shorter sessions spaced out over time. You might find that you can get far more done in three 2- hour sessions than in one 6-hour session.

This suggestion does have an exception. When you are so engrossed in a textbook that you cannot put it down or when you are consumed by an idea for a term paper and cannot think of anything else, keep going. The successful student within you has taken over. Enjoy the ride.

Be aware of attitudes. People who think history is boring tend to have trouble remembering dates and historical events. People who believe math is difficult often have a hard time recalling mathematical equations and formulas. All of us can forget information that contradicts our opinions.

If you think a subject is boring, remind yourself that everything is related to everything else. Look for connections that relate to your own interests.

Being aware of your attitudes is not the same as fighting them or struggling to give them up. Just notice your attitudes, and be willing to put them on hold. For more ideas, see the power process: Notice your pictures and let them go.

Elaborate. According to Harvard psychologist Daniel Schacter, all courses in memory improvement are based on a single technique—elaboration. Elaboration means consciously encoding new information. Repetition is one basic way to elaborate. However, current brain research indicates that other types of elaboration are more effective for long-term memory (Schacter 2002, 35-36).

One way to elaborate is to ask yourself questions about incoming information: Does this remind me of something or someone I already know?, Is this similar to a technique that I already use?, and Where and when can I use this information?

The same idea applies to more complex material. When you meet someone new, for example, ask yourself, Does she remind me of someone else?

Intend to remember. To instantly enhance your memory, form the simple intention to learn it now rather than later. The intention to remember can be more powerful than any single memory technique.

You can build on your intention with simple tricks. During a lecture, for example, pretend that you’ll be quizzed on the key points at the end of the period. Imagine that you’ll get a $5 reward for every correct answer.

Memory Techniques—Recall It

Sometimes, recalling information can be difficult, especially if you are processing a lot of information or are studying multiple subjects at once. You might need to recall information when you are taking a test or learning a new concept that relates to something you already learned. You can use some of the following recall techniques to help you recall information when you need it.

Remember something else. When you are stuck and can’t remember something that you’re sure you know, remember something else that is related to it.

If you can’t remember your great-aunt’s name, remember your great-uncle’s name. During an economics exam, if you can’t remember anything about the aggregate demand curve, recall what you do know about the aggregate supply curve. If you cannot recall specific facts, remember the example that the instructor used during his lecture. Any piece of information is encoded in the same area of the brain as a similar piece of information. You can unblock your recall by stimulating that area of your memory.

A brainstorm is a good memory jog. If you are stumped when taking a test, start writing down lots of answers to related questions, and—pop!—the answer you need may appear.

Notice when you do remember. Everyone has a different memory style. Some people are best at recalling information they’ve read. Others have an easier time remembering what they’ve heard, seen, or done.

To develop your memory, notice when you recall information easily, and ask yourself what memory techniques you’re using naturally. Also notice when you find it difficult to recall information. Be a reporter. Get the facts and then adjust your learning techniques. And congratulate yourself when you remember.

Use it before you lose it. Even information encoded in long-term memory becomes difficult to recall when we don’t use it regularly. The pathways to the information become faint with disuse. For example, you can probably remember your current phone number. What was your phone number 10 years ago?

This example points to a powerful memory technique. To remember something, access it a lot. Read it, write it, speak it, listen to it, apply it. Find some way to make contact with the material regularly. Each time you do so, you widen the neural pathway to the material and make it easier to recall the next time.

Another way to make contact with the material is to teach it. Teaching demands mastery. When you explain the function of the pancreas to a fellow student, you discover quickly whether you really understand it yourself. Study groups are especially effective because they put you on stage. The friendly pressure of knowing that you’ll teach the group helps focus your attention.

Adopt the attitude that you never forget. Instead of saying, I don’t remember, say, It will come to me. The latter statement implies that the information you want is encoded in your brain and that you can retrieve it—just not right now. You might be surprised to find that the information obediently pops into mind.

Understanding the Brain

When asked about brain-based learning, skeptics might say, Well, obviously—how could learning be based anywhere other than the brain?

That’s a fair question. One answer is this: All learning does involve the brain, but some learning strategies use more of the brain’s unique capacities.

Brains Thrive on Meaningful Patterns

Your brain is a pattern-making machine. It excels at taking random bits of information and translating them into meaningful wholes. Build on this capacity with elaborative rehearsal. For example:

- Use your journal. Write Discovery Statements and Intention Statements like the ones discussed in this course. Journal entries prompt you to elaborate on what you hear in class and read in your textbooks. You can create your own writing prompts. For example: In class today, I discovered that.... and To overcome my confusion about this topic, I intend to....

- Send yourself a message. Imagine that an absent classmate has asked you to send her an e-mail about what happened in class today. Write a reply and send it to yourself. You’ll actively process your recent learning—and create a summary that you can use to review for tests.

- Play with ideas. Copy your notes onto 3 × 5 cards—one fact or idea per card. Then, see whether you can arrange these into new patterns—by chronological order, order of importance, or main ideas and supporting details.

Brains Thrive on Rich Sensory Experience

Your brain’s contact with the world comes through your five senses, so anchor your learning in as many senses as possible. Beyond sight and sound, this can include touch, movement, smell, and taste:

- Create images. Draw mind map summaries of your readings and lecture notes. Include visual images. Put the main ideas in larger letters and brighter colors.

- Translate ideas into physical objects. If one of your career goals is to work from a home office, for example, then create a model of your ideal workspace. Visit an art supplies store to find appropriate materials.

- Immerse yourself in concrete experiences. Say you’re in a music appreciation class and learning about jazz. Go to a local jazz club or concert to see and hear a live performance.

Brains Thrive on Long-Term Care

Starting now, adopt habits to keep your brain lean and fit for life. Consider these research-based suggestions from the Alzheimer’s Association (2012):

- Stay mentally active. If you sit at a desk most of the workday, take a hiking class or start a garden. If you seldom travel, start reading maps of new locations and plan a cross- country trip. Play challenging games and work crossword puzzles. Seek out museums, theaters, concerts, and other cultural events. Even after you graduate, consider learning another language or a musical instrument. Learning gives your brain a workout, much like sit-ups condition your abs.

- Stay socially active. Having a network of supportive friends can reduce stress levels. In turn, stress management helps to maintain connections between brain cells. Stay socially active by working, volunteering, and joining clubs.

- Stay physically active. Physical activity promotes blood flow to the brain. It also reduces the risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other diseases that can impair brain function. Exercise that includes mental activity—such as planning a jogging route and watching for traffic signals—offers added benefits.

- Adopt a brain-healthy diet. A diet rich in dark-skinned fruits and vegetables boosts your supply of antioxidants—natural chemicals that nourish your brain. Examples of these foods are raisins, blueberries, blackberries, strawberries, raspberries, kale, spinach, brussels sprouts, alfalfa sprouts, and broccoli. Avoid foods that are high in saturated fat and cholesterol, which may increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

- Protect your heart. In general, what’s good for your heart is good for your brain. Protect both organs by eating well, exercising regularly, managing your weight, staying tobacco- free, and getting plenty of sleep. These habits reduce your risk of heart attack, stroke, and other cardiovascular conditions that interfere with blood flow to the brain.

Mnemonic Devices, Part 1

Mnemonic is pronounced “ne-MON-ik.” The word refers to tricks that can increase your ability to recall everything from grocery lists to speeches.

Some entertainers use mnemonic devices to perform seemingly impossible feats of memory, such as recalling the names of everyone in a large audience after hearing them just once. Using mnemonic devices, speakers can go for hours without looking at their notes. The possibilities for students are endless.

There is a catch, though. Mnemonic devices have three serious limitations:

- They don’t always help you understand or digest material. Mnemonics rely only on rote memorization.

- The mnemonic device itself is sometimes complicated to learn and time consuming to develop.

- Mnemonic devices can be forgotten.

In spite of their limitations, mnemonic devices can be powerful. There are five general categories: new words, creative sentences, rhymes and songs, the loci system, and the peg system.

New words. Acronyms are words created from the initial letters of a series of words. Examples include

- NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration)

- laser (light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation).

You can make up your own acronyms to recall a series of facts. A common mnemonic acronym is Roy G. Biv, which has helped millions of students remember the colors of the visible spectrum (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet). The mnemonic IPMAT helps biology students remember the stages of cell division (interphase, prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase). The mnemonic OCEAN helps psychology students recall the five major personality factors: open-mindedness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.

Creative sentences. Acrostics are sentences that help you remember a series of letters that stand for something. For example, the first letters of the words in the sentence Every good boy does fine (E, G, B, D, and F) are the music notes of the lines of the treble clef staff.

Rhymes and songs. Madison Avenue (in New York City) advertising executives spend billions of dollars a year on advertisements designed to burn their messages into your memory. The song “It’s the Real Thing” was used to market Coca-Cola, despite the soda’s artificial ingredients.

Rhymes have been used for centuries to teach basic facts. I before e, except after c has helped many students on spelling tests.

Mnemonic Devices, Part 2

In addition to making up new words or creating rhymes and songs, you might try the loci system and peg system to learn new information. Try them to see which one works best for you.

Loci system. The word loci is the plural of locus, a synonym for place or location. Use the loci system to create visual associations with familiar locations. Unusual associations are the easiest to remember.

The loci system is an old one. Ancient Greek orators used it to remember long speeches, and politicians use it today. For example, if a politician’s position were that road taxes must be raised to pay for school equipment, his loci visualizations before a speech might look like the following.

First, as he walks in the door of his house, he imagines a large porpoise jumping through a hoop. This reminds him to begin by telling the audience the purpose of his speech.

Next, he visualizes his living room floor covered with paving stones, forming a road leading into the kitchen. In the kitchen, he pictures dozens of schoolchildren sitting on the floor because they have no desks.

Now it’s the day of the big speech. The politician is nervous. He’s perspiring so much that his clothes stick to his body. He stands up to give his speech and his mind goes blank. Then, he starts thinking to himself:

I can remember the rooms in my house. Let’s see, I’m walking in the front door and— wow!—I see a porpoise. That reminds me to talk about the purpose of my speech. And then there’s that road leading to the kitchen. Say, what are all those kids doing there on the floor? Oh, yeah, now I remember—they have no desks! We need to raise taxes on roads to pay for their desks and the other stuff they need in classrooms.

Peg system. The peg system is a device that employs key words paired with numbers. Each word forms a “peg” on which you can “hang” mental associations. To use this system effectively, learn the following peg words and their associated numbers:

- bun goes with 1

- shoe goes with 2

- tree goes with 3

- door goes with 4

- hive goes with 5

- sticks goes with 6

- heaven goes with 7

- gate goes with 8

- wine goes with 9

- hen goes with 10

You can use the peg system to remember the Bill of Rights (the first 10 amendments to the US Constitution). For example, amendment number four is about protection from unlawful search and seizure. Imagine people knocking at your door who are demanding to search your home. This amendment means that you do not have to open your door unless those people have a proper search warrant.

References

Alzheimer’s Association. “Brain health.” www.alz.org/brainhealth/overview.asp (accessed November 8, 2012).

Schacter, Daniel. The Seven Sins of Memory: How the Mind Forgets and Remembers. Wilmington, MA: Mariner Books, 2002.