Diversity and inclusion in the workforce is important to understand as you prepare for your future career. Diversity is not simply a box to be checked; rather, it is an approach to business that unites ethical management and high performance. Business leaders in the global economy recognize the benefits of a diverse workforce and see it as an organizational strength, not as a mere slogan or a form of regulatory compliance with the law. They recognize that diversity can enhance performance and drive innovation; conversely, adhering to the traditional business practices of the past can cost them talented employees and loyal customers.

A study by global management consulting firm McKinsey & Company indicates that businesses with gender and ethnic diversity outperform others. According to Mike Dillon, chief diversity and inclusion officer for PwC in San Francisco, “attracting, retaining and developing a diverse group of professionals stirs innovation and drives growth.”

Living this goal means not only recruiting, hiring, and training talent from a wide demographic spectrum but also including all employees in every aspect of the organization.

Workplace Diversity

The twenty-first century workplace features much greater diversity than was common even a couple of generations ago. Individuals who might once have faced employment challenges because of religious beliefs, ability differences, or sexual orientation now regularly join their peers in interview pools and on the job. Each may bring a new outlook and different information to the table; employees can no longer take for granted that their coworkers think the same way they do. This pushes them to question their own assumptions, expand their understanding, and appreciate alternate viewpoints. The result is more creative ideas, approaches, and solutions. Thus, diversity may also enhance corporate decision-making.

Communicating with those who differ from us may require us to make an extra effort and even change our viewpoint, but it leads to better collaboration and more favorable outcomes overall, according to David Rock, director of the Neuro-Leadership Institute in New York City, who says diverse coworkers “challenge their own and others’ thinking.”

According to the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), organizational diversity now includes more than just racial, gender, and religious differences. It also encompasses different thinking styles and personality types, as well as other factors such as physical and cognitive abilities and sexual orientation, all of which influence the way people perceive the world. “Finding the right mix of individuals to work on teams, and creating the conditions in which they can excel, are key business goals for today’s leaders, given that collaboration has become a paradigm of the twenty-first century workplace,” according to an SHRM article.

Attracting workers who are not all alike is an important first step in the process of achieving greater diversity. However, managers cannot stop there. Their goals must also encompass inclusion, or the engagement of all employees in the corporate culture. “The far bigger challenge is how people interact with each other once they’re on the job,” says Howard J. Ross, founder and chief learning officer at Cook Ross, a consulting firm specializing in diversity. “Diversity is being invited to the party; inclusion is being asked to dance. Diversity is about the ingredients, the mix of people and perspectives. Inclusion is about the container—the place that allows employees to feel they belong, to feel both accepted and different.”

Workplace diversity is not a new policy idea; its origins date back to at least the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (CRA) or before. Census figures show that women made up less than 29 percent of the civilian workforce when Congress passed Title VII of the CRA prohibiting workplace discrimination. After passage of the law, gender diversity in the workplace expanded significantly. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the percentage of women in the labor force increased from 48 percent in 1977 to a peak of 60 percent in 1999. Over the last five years, the percentage has held relatively steady at 57 percent. Over the past forty years, the total number of women in the labor force has risen from 41 million in 1977 to 71 million in 2017.

The BLS projects that the number of women in the U.S. labor force will reach 92 million in 2050 (an increase that far outstrips population growth).

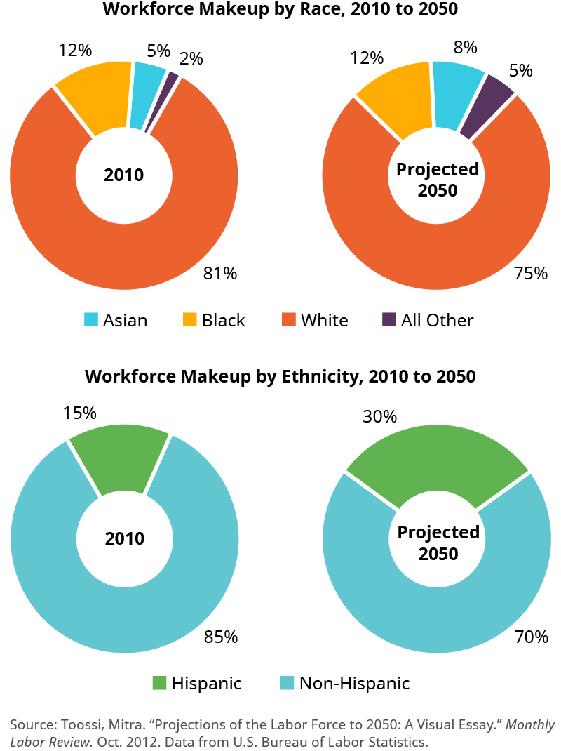

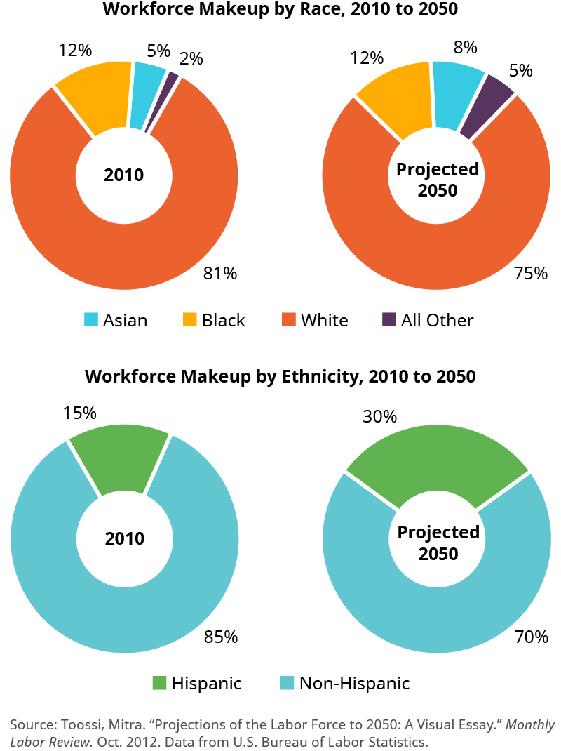

The statistical data show a similar trend for African American, Asian American, and Hispanic workers (Figure below). Just before passage of the CRA in 1964, the percentages of minorities in the official on-the-books workforce were relatively small compared with their representation in the total population. In 1966, Asians accounted for just 0.5 percent of private-sector employment, with Hispanics at 2.5 percent and African Americans at 8.2 percent.

However, Hispanic employment numbers have significantly increased since the CRA became law; they are expected to more than double from 15 percent in 2010 to 30 percent of the labor force in 2050. Similarly, Asian Americans are projected to increase their share from 5 to 8 percent between 2010 and 2050.

(Image by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0)

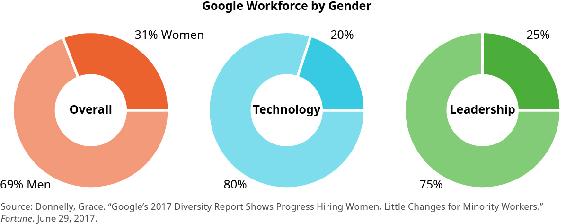

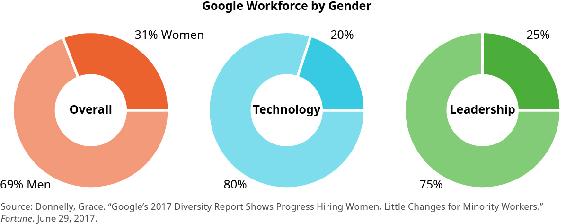

Much more progress remains to be made, however. For example, many people think of the technology sector as the workplace of open-minded millennials. Yet Google, as one example of a large and successful company, revealed in its latest diversity statistics that its progress toward a more inclusive workforce may be steady but it is very slow. Men still account for the great majority of employees at the corporation; only about 30 percent are women, and women fill fewer than 20 percent of Google’s technical roles (Figure below). The company has shown a similar lack of gender diversity in leadership roles, where women hold fewer than 25 percent of positions. Despite modest progress, an ocean-sized gap remains to be narrowed. When it comes to ethnicity, approximately 56 percent of Google employees are white. About 35 percent are Asian, 3.5 percent are Latino, and 2.4 percent are black, and of the company’s management and leadership roles, 68 percent are held by whites.

OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0)

Google is not alone in coming up short on diversity. Recruiting and hiring a diverse workforce has been a challenge for most major technology companies, including Facebook, Apple, and Yahoo (now owned by Verizon); all have reported gender and ethnic shortfalls in their workforces.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has made available 2014 data comparing the participation of women and minorities in the high-technology sector with their participation in U.S. private-sector employment overall, and the results show the technology sector still lags.

Compared with all private-sector industries, the high-technology industry employs a larger share of whites (68.5%), Asian Americans (14%), and men (64%), and a smaller share of African Americans (7.4%), Latinos (8%), and women (36%). Whites also represent a much higher share of those in the executive category (83.3%), whereas other groups hold a significantly lower share, including African Americans (2%), Latinos (3.1%), and Asian Americans (10.6%). In addition, and perhaps not surprisingly, 80 percent of executives are men and only 20 percent are women. This compares negatively with all other private-sector industries, in which 70 percent of executives are men and 30 percent women.

Technology companies are generally not trying to hide the problem. Many have been publicly releasing diversity statistics since 2014, and they have been vocal about their intentions to close diversity gaps. More than thirty technology companies, including Intel, Spotify, Lyft, Airbnb, and Pinterest, each signed a written pledge to increase workforce diversity and inclusion, and Google pledged to spend more than $100 million to address diversity issues.

Diversity and inclusion are positive steps for business organizations, and despite their sometimes slow pace, the majority are moving in the right direction. Diversity strengthens the company’s internal relationships with employees and improves employee morale, as well as its external relationships with customer groups. Communication, a core value of most successful businesses, becomes more effective with a diverse workforce. Performance improves for multiple reasons, not the least of which is that acknowledging diversity and respecting differences is the ethical thing to do.24

Generational Differences in the Workforce

Today we have four different generations in the workforce and each generation differs in terms of values, communication style, and life experiences. Each group brings valuable contributions to the workplace.

Each generation is a subculture with a sense of reality based on formative world and national events, technological innovations and socio-cultural values. To understand how that experience impacts communication, it’s instructive to consider how the different generations view technology and communications media. The following examples are based on an analysis of generational differences:25

Table 3.2 – Examples of Generational Differences

| |

Traditionalists

|

Baby Boomers

|

Generation X

|

Millennials

|

Generation Z

|

|

Technology is . . .

|

Hoover Dam

|

The microwave

|

Internet

|

Hand-held devices

|

Virtual

|

|

Communicate via . . .

|

Rotary phones

|

Touch-tone phones

|

Cell phones

|

Internet & Text

|

Social Media

|

Every generation develops expertise with communication formats and media that reflect their situational reality. For example, Traditionalists tend to have a more formal communication style, with a strict adherence to written grammatical rules and a strong cultural structure. Baby Boomers tend to prefer a more informal and collaborative approach. Gen X communications tend to be more blunt and direct: just the facts. Millennial and Gen Z communication is technology-dependent. As an Ad Council article notes, these generations are driving a truncation of the English language, shortening words (e.g., totally becomes totes) and abbreviating phrases into one or two-syllable “words,” which may or may not be spoken aloud (e.g., FOMO for “fear of missing out” and TIL for “today I learned”).

For additional perspective, see McCrindle Research “How to Speak Gen Z” infographic. These clippings have their roots in texting language: a shorthand that’s optimized for the communications media and immediate gratification expectations of mobile communication.

Texting

Texting is a cross-generational trend—something that nearly all adults in America participate in. For perspective on texting, read onereach.com’s “45 Texting Statistics that Prove Businesses Need To Start Taking Texting Seriously.” A few excerpts, for perspective:

- Over 80% of American adults text, making it the most common cell phone activity. (Pew Internet)

- The average adult spends a total of 23 hours a week texting (USA Today)

- The average Millennial exchanges an average of 67 text messages per day (Business Insider)

- On average, Americans exchange twice as many texts as they do calls (Nielsen)

- Only 43% of smartphone owners use their phone to make calls, but over 70% of smartphone users text (Connect Mogul)

Bridging the Generation Gap

Each generation brings not only a frame of reference but also a set of competencies—and expectations—based on how they view the world and their place in it. The challenge for both businesses and individuals is that we now have five generations in the workforce. Differences in generational communication style and media are, effectively, language barriers. To the extent that individuals can’t translate, the communication gaps are a hindrance to effective collaboration and, by extension, achievement of critical goals and objectives. The communication disconnect can also affect employee morale and productivity.

The opportunity in this situation is to leverage specific generational strengths and decrease points of friction. The best case scenario is to create a culture and opportunities that encourage cross-generational sharing and mentoring. As Nora Zelevansky wrote in a piece for Coca-Cola: “In order to master intergenerational communication, it is necessary to understand some broad generalizations about the generations and then move beyond those to connect as individuals.”26

In a related trend, the model of talent management is changing. As discussed in a Sodexo report on 2017 Workplace Trends, we’re moving to a model of shared learning, where workers of all ages contribute to each other’s growth and development.27 Indeed, the researchers identified “intergenerational agility” as a critical aspect of the employee and employer value proposition. Business benefits of intergenerational learning include increased efficiency, productivity and competitive positioning. Two statistics that suggest the culture and communication gaps can be bridged:28

- 90 percent of Millennials believe that Boomers bring substantial experience and knowledge to the workplace

- 93 percent of Baby Boomers believe that Millennials bring new skills and ideas to the workplace.

The diversity of the intergenerational workplace isn’t just a development—it’s a creative opportunity.

Professor Mariano Sánchez of the University of Granada in Spain sees the opportunity in cultivating ”generational intelligence;” specifically, “organizing activities that raise generational awareness, connect generations and help them work better together—exchanging knowledge, ideas, skills and more to enhance the broad skill sets everyone needs in today’s jobs.”29

According to Jason Dorsey, Millennial and Gen Z researcher and co-founder of The Center for Generational Kinetics, “The key is getting each person to recognize that everyone has different communication skills that can be harnessed to best support the organization.”30 Incorporating multiple communication media in meetings and to facilitate ongoing discussion/collaboration allows members of different generations to share expertise and demonstrate the value of a particular medium. Selecting technology that supports multiple ways of communicating and collaborating can also leverage collective strengths and create fertile ground. For example, using a videoconferencing platform allows for participants to connect visually and participate virtually, with audio, screen sharing and recording capabilities.

|

Activity 3.6: Generational Differences in the Workplace

|

|

After reading the section on generational differences in the workplace, reflect on your experiences at school, work and in your community and answer the following questions:

What generation do you identify with?

How closely do you resemble some of the descriptors used to describe this generation? Explain and give examples.

Why do you think it is important to understand the generational differences in the workplace? Explain and give examples.

Understanding the broad generational generalizations are important to help understand different work styles and preferences, however it is essential to move beyond generalizations and connect as individuals.

|