6.5: Production Possibilities

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 45218

- Anonymous

- LibreTexts

Learning Objectives

- Where do the gains from trade come from?

- What determines who produces which good?

So far we have discussed several different ways in which individuals trade with one another, including individual bargaining and Internet sites such as eBay and craigslist. We have considered situations with one seller and one buyer, one seller and many buyers, and many sellers and buyers. But why do we trade so much? Why is trade so central to our lives and indeed to the history of the human race?

On a typical craigslist website, many services are offered for sale. They are listed under categories such as financial, legal, computer, beauty, and so on. If you click on one of these headings and follow one of the offers, you typically find that someone is willing to provide a service, such as legal advice, in exchange for money. Sometimes there are offers to barter: to exchange a service for some other service or for some specific good. For example, we found the following offers listed on craigslist.These are actual offers that we found on craigslist, edited slightly for clarity.

Hello, I am looking for a dentist/oral surgeon who is willing to remove my two wisdom teeth in exchange for furniture repair and refinishing. If preferred, I’ll come to your office and show you my teeth beforehand. Take a look at some of the work I have posted on my web page…quality professional furniture restoration. Bring new life to your antiques!

We are new to the area and are looking for a babysitter for casual or part-time help with our three little girls. My husband is a chiropractor and offers adjustments, and I am a vegan and raw foods chef offering either culinary classes or prepared food in exchange for a few hours of babysitting each week.

I have a web design company,…I figure I’d offer to barter in this slow economy. If you got something you’d be willing to trade for a website, let me know and maybe we can work something out!

These offers provide a glimpse into why people trade. Some people are relatively more productive than others in the production of certain goods or services. Hence it makes sense that people should perform those tasks they are relatively good at and then in some way exchange goods and services. These offers reveal both a reason for trade and a mechanism for trade.

As individuals, we are involved in the production of a very small number of goods and services. The person who cuts your hair is probably not a financial advisor. It is unlikely that your economics professor also moonlights as a bouncer at a local nightclub. By contrast, we buy thousands of goods and services—many more goods and services than we produce. We specialize in production and generalize in consumption. One motivation for trade is this simple fact: we typically don’t consume the goods we produce, and we certainly want to consume many more goods than we produce. Yet that prompts the question of why society is organized this way. Why do we live in such a specialized world?

To address this question, we leave our modern, complicated world—the world of eBay, craigslist, and the Internet—behind and study some very simple economies instead. In fact, we begin with an economy that has only one individual. This allows us to see what a world would look like without any trade at all. Then we can easily see the difference that trade makes.

Production Possibilities Frontier for a Single Individual

Inspired by the craigslist posts that we saw earlier, imagine an economy where people care about only two things: web pages and vegan meals. Our first economy has a single individual—we call him Julio—who has 8 hours a day to spend working. Julio can spend his time in two activities: web design and preparing vegan meals. To be concrete, suppose he can produce 1 web page per hour or 2 vegan meals per hour. Julio faces a time allocation problem: how should he divide his time between these activities?We study the time allocation problem in Chapter 4 "Everyday Decisions".

The answer depends on both Julio’s productivity and his tastes. We start by looking at his ability to produce web pages and vegan meals in a number of different ways. Table 6.5.1 "Julio’s Production Ability" shows the quantity of each good produced per hour of Julio’s time. Julio can produce either 2 vegan meals or 1 web page in an hour. Put differently, it takes Julio half an hour to prepare a meal and 1 hour to produce a web page. These are the technologies—the ways of producing output from inputs—that are available to Julio.

Toolkit: Section 31.17 "Production Function"

A technology is a means of producing output from inputs.

| Vegan Meals per Hour | Web Pages per Hour |

|---|---|

| 2 | 1 |

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\): Julio’s Production Ability

We could write these two technologies as equations:

\[quantity\ of\ vegan\ meals\ =\ 2\ ×\ hours\ spent\ cooking\]

and

\[quantity\ of\ web\ pages\ =\ hours\ spent\ on\ web\ design.\]

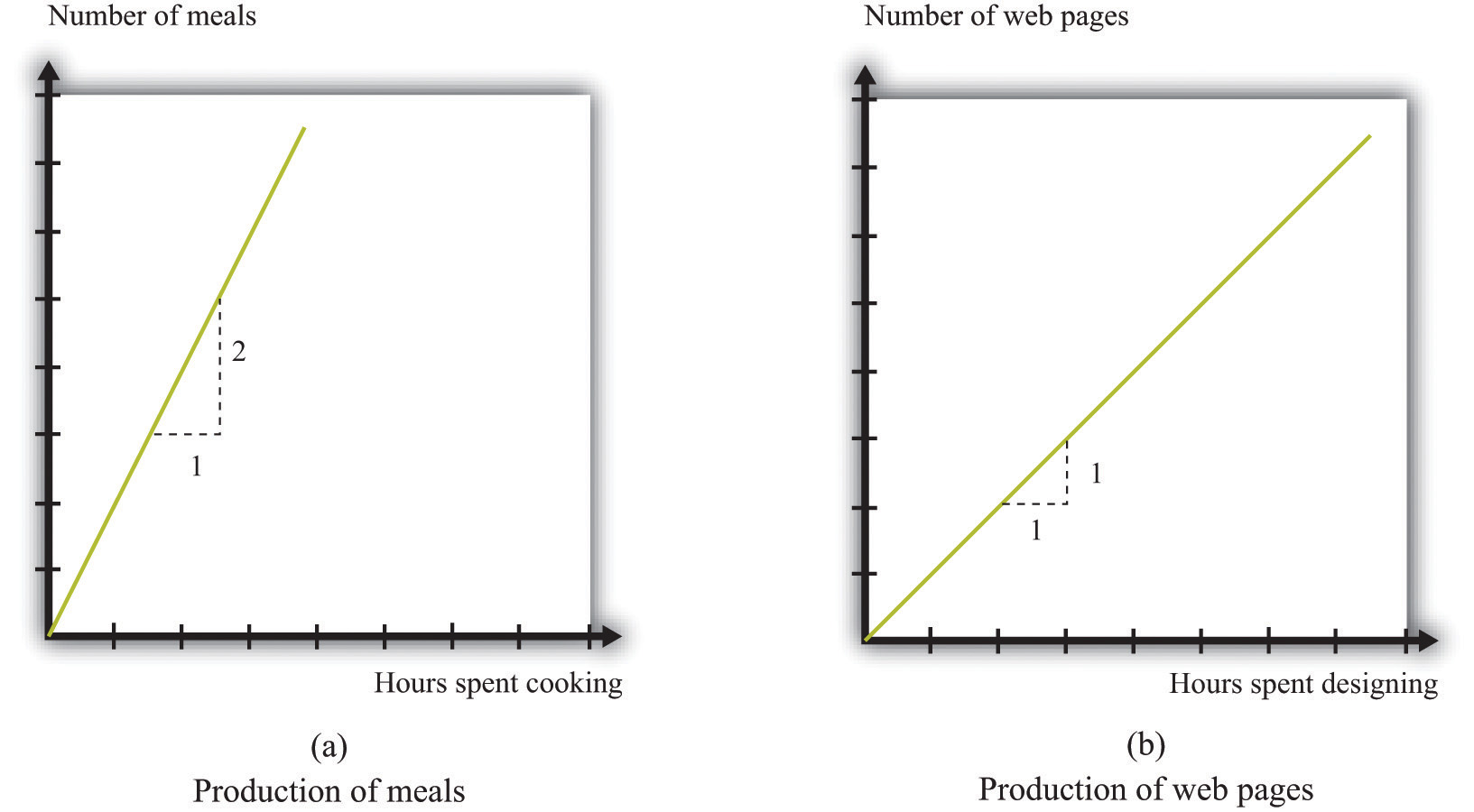

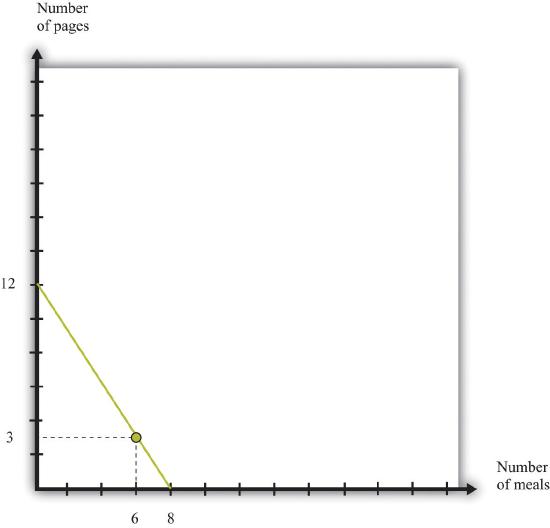

Or we can draw these two technologies ( Figure 6.5.1 "Julio’s Production Ability"). The equations, the figure, and the table are three ways of showing exactly the same information.

These figures show Julio’s technologies for producing vegan meals and producing web pages.

When we add in the further condition that Julio has 8 hours available each day, we can construct his different possible production choices—the combinations of web pages and vegan cuisine that he can produce given his abilities and the time available to him. The first two columns of Table 6.5.2 "Julio’s Production Possibilities" describe five ways Julio might allocate his 8 hours of work time. In the first row, Julio allocates all 8 hours to preparing vegan meals. In the last row, he spends all of his time in web design. The other rows show what happens if he spends some time producing each service. Note that the total hours spent in the two activities is always 8 hours.

The third and fourth columns provide information on the number of vegan meals and web pages that Julio produces. Looking at the first row, if he works only on vegan meals, then he produces 16 meals and 0 web pages. If Julio spends all of his time designing web pages, then he produces 0 vegan meals and 8 web pages.

| Time Spent Producing | Goods Produced | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vegan Meals | Web Pages | Vegan Meals | Web Pages |

| 8 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| 2 | 6 | 12 | 2 |

| 4 | 4 | ||

| 6 | 2 | ||

| 0 | 8 | 0 | 8 |

Table \(\PageIndex{2}\): Julio’s Production Possibilities

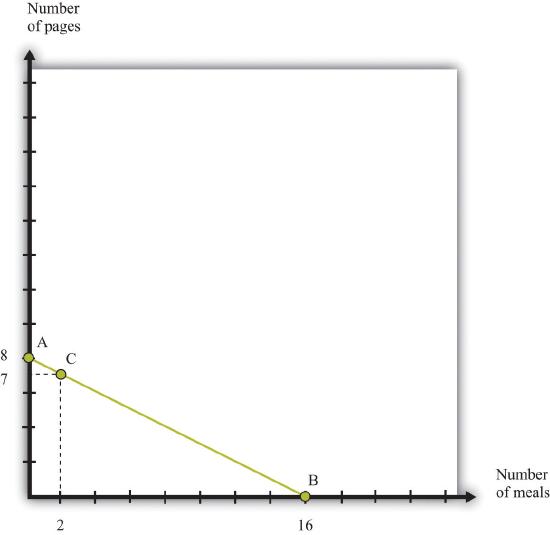

We can also illustrate this table in a single graph ( Figure 6.5.2 "Julio’s Production Possibilities") that summarizes Julio’s production possibilities. The quantity of vegan meals is on the horizontal axis, and the quantity of web pages is on the vertical axis. To understand Figure 6.5.2 "Julio’s Production Possibilities", first consider the vertical and horizontal intercepts. If Julio spends the entire 8 hours of his working day on web design, then he will produce 8 web pages and no vegan meals (point A). If Julio instead spends all his time cooking vegan meals and none on web design, then he can produce 16 vegan meals and 0 web pages (point B).

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Julio’s Production Possibilities

Julio’s production possibilities frontier shows the combinations of meals and web pages that he can produce in an 8-hour day.

The slope of the graph is −1/2. To see why, start at the vertical intercept where Julio is producing only web pages. Suppose that he reduces web-page production by 1 page. This means he will produce only 7 web pages, which requires 7 hours of his time. The hour released from the production of web design can now be used to prepare vegan meals. This yields 2 vegan meals. The resulting combination of web pages and vegan meals is indicated as point C. Comparing points A and C, we can see why the slope is −1/2. A reduction of web-page production by 1 unit (the rise) yields an increase in vegan meals production of 2 (the run). The slope—rise divided by run—is −1/2.

Given his technology and 8 hours of working time, all the combinations of vegan meals and web pages that Julio can produce lie on the line connecting A and B. We call this the production possibilities frontier. Assuming that Julio equally likes both web design and vegan meals and is willing to work 8 hours, he will choose a point on this frontier.All of this may seem quite familiar. The production possibility frontier for a single individual is the same as the time budget line for an individual. See Chapter 4 "Everyday Decisions" for more information.

Toolkit: Section 31.12 "Production Possibilities Frontier"

The production possibilities frontier shows the combinations of goods that can be produced with available resources. It is generally illustrated for two goods.

What is the cost to Julio of cooking one more meal? To cook one more meal, Julio must take 30 minutes away from web design. Because it takes 30 minutes to produce the meal, and Julio produces 1 web page per hour, the cost of producing an additional vegan meal is half of a web page. This is his opportunity cost: to do one thing (produce more vegan meals), Julio must give up the opportunity to do something else (produce web pages). Turning this around, we can determine the opportunity cost of producing an extra web page in terms of vegan meals. Because Julio can produce 1 web page per hour or cook 2 meals per hour, the opportunity cost of 1 web page is 2 vegan meals. The fact that Julio must give up one good (for example, web pages) to get more of another (for example, vegan meals) is a direct consequence of the fact that Julio’s time is scarce.

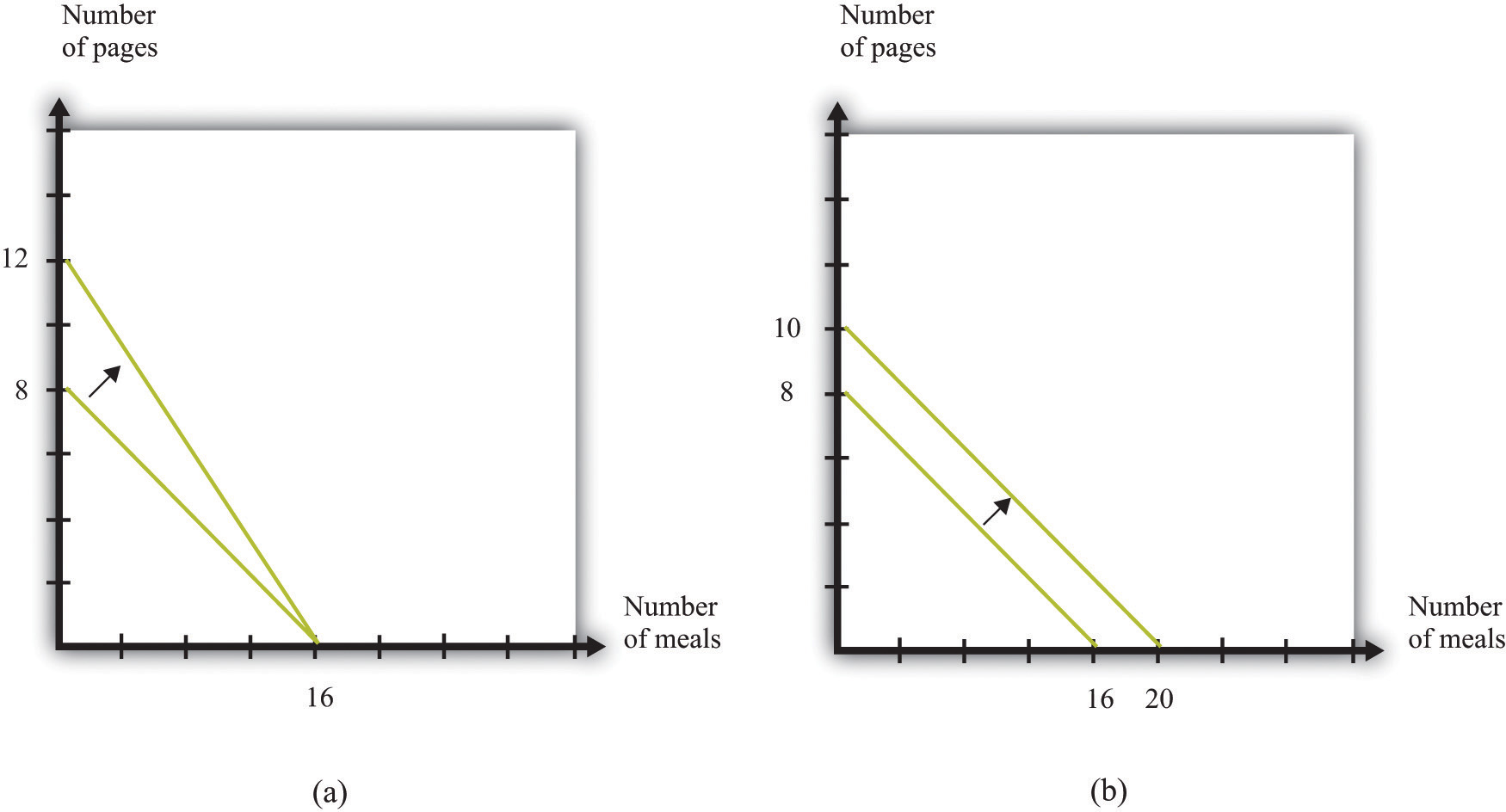

Could Julio somehow produce more web pages and more vegan meals? There are only two ways in which this could happen. First, his technology could improve. If Julio were able to become better at either web design or vegan meals, his production possibilities frontier would shift outward. For example, if he becomes more skilled at web design, he might be able to produce 3 (rather than 2) web pages in 2 hours. Then the new production possibilities frontier would be as shown in part (a) of Figure 6.5.3 "Two Ways of Shifting the Production Possibilities Frontier Outward".

There are two ways in which Julio could produce more in a day: he could become more skilled, or he could work harder.

Alternatively, Julio could decide to work more. We have assumed that the amount of time that Julio works is fixed at 8 hours. Part (b) of Figure 6.5.3 "Two Ways of Shifting the Production Possibilities Frontier Outward" shows what the production possibilities frontier would look like if Julio worked 10 hours per day instead of 8 hours. This also has an opportunity cost. If Julio works longer, he has less time for his leisure activities.

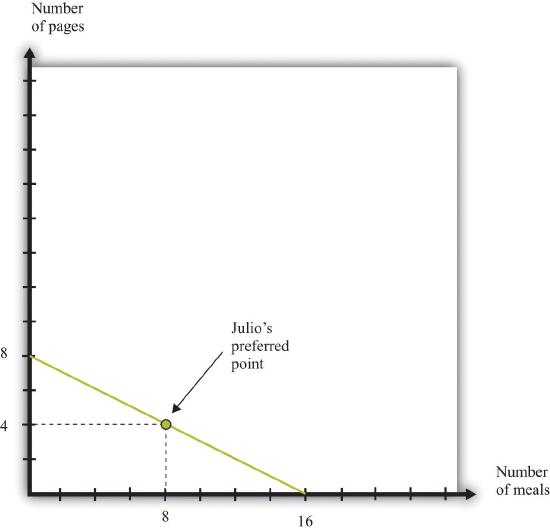

We have not yet talked about where on the frontier Julio will choose to allocate his time. This depends on his tastes. For example, he might like to have 2 vegan meals for each web page. Then he would consume 4 web pages and 8 meals, as in Figure 6.5.4 "Julio’s Allocation of Time to Cooking Meals and Producing Web Pages".

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Julio’s Allocation of Time to Cooking Meals and Producing Web Pages

If Julio likes to consume pages and meals in fixed proportions (2 vegan dishes for every web page), he will allocate his time to achieve the point shown in the figure.

The Production Possibilities Frontier with Two People

If this were the end of the story, we would not have seen the advertisements on craigslist to trade vegan meals or web pages. Things become more interesting and somewhat more realistic when we add another person to our economy.

Hannah has production possibilities that are summarized in Table 6.5.3 "Production Possibilities for Julio and Hannah". She can produce 1 vegan meal in an hour or produce 1.5 web pages in an hour. Hannah, like Julio, has 8 hours per day to allocate to production activities. In Table 6.5.3 "Production Possibilities for Julio and Hannah" we have also included their respective opportunity costs of producing web pages and vegan meals.

| Vegan Meals per Hour | Web Pages per Hour | Opportunity Cost of Vegan Meals (in Web Pages) | Opportunity Cost of Web Pages (in Vegan Meals) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Julio | 2 | 1 | 1/2 | 2 |

| Hannah | 1 | 1.5 | 3/2 | 2/3 |

Table \(\PageIndex{3}\): Production Possibilities for Julio and Hannah

Table 6.5.3 "Production Possibilities for Julio and Hannah" reveals that Hannah is more productive than Julio in the production of web pages. By contrast, Julio is more productive in vegan meals. Hannah’s production possibilities frontier is illustrated in Figure 6.5.5 "Hannah’s Production Possibilities Frontier". It is steeper than Julio’s because the opportunity cost of vegan meals is higher for Hannah than it is for Julio.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): Hannah’s Production Possibilities Frontier

Hannah’s production possibilities frontier is steeper than Julio’s.

Economists use the ideas of absolute advantage and comparative advantage to compare the productive abilities of Hannah and Julio.

Toolkit: Section 31.13 "Comparative Advantage"

Comparative advantage and absolute advantage are used to compare the productivity of people (or firms or countries) in the production of a good or a service. A person has an absolute advantage in the production of a good if that person can produce more of that good in a unit of time than another person. A person has a comparative advantage in the production of one good if the opportunity cost, measured by the lost output of the other good, is lower for that person than for another person.

Both absolute and comparative advantage are relative concepts because they compare two people. In the case of absolute advantage, we compare the productivity of two people for a given good. In the case of comparative advantage, we compare two people and two goods because opportunity cost is defined across two goods (web pages and vegan meals in our example). Comparing Hannah and Julio, we see that Hannah has an absolute advantage in the production of web pages. She is better at producing web pages than Julio. By contrast, Julio has an absolute advantage in the production of vegan meals. Therefore, it is not surprising that Hannah also has a comparative advantage in the production of web pages—the opportunity cost of web pages is lower for her than it is for Julio—whereas Julio has a comparative advantage in vegan meals.

It is entirely possible for one person to have an absolute advantage in the production of both goods. For example, were Hannah’s productivity in both activities to double, she would be better both at both web design and vegan meals. However, her opportunity cost of web pages would be unchanged. Julio would still have a comparative advantage in vegan meals. In general, one person always has a comparative advantage in one activity, while the other person has a comparative advantage in the other activity (the only exception is the case where the two individuals have exactly the same opportunity costs).

Suppose that Hannah’s tastes for vegan meals and web pages are the same as Julio’s: like Julio, Hannah wants to consume 2 meals for every web page. Acting alone, she would work for 2 hours in web design and spend 6 hours cooking, ending up with 3 web pages and 6 meals. But there is something very odd going on here. Julio, who is good at preparing meals, spends half his time on web design. Hannah, who is good at web design, spends three-quarters of her time cooking. Each has to spend a lot of time doing an activity at which he or she is unproductive.

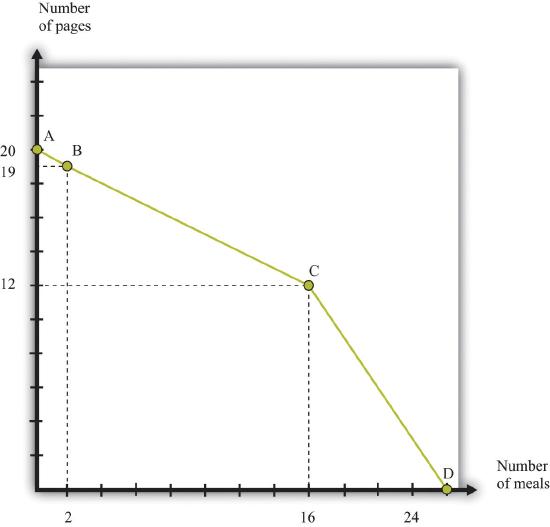

This is where we see the possibility of gains from trade. Imagine that Julio and Hannah join together and become a team. What is their joint production possibilities frontier? If both Julio and Hannah devote their 8 hours of time to the production of web pages, then the economy can produce 20 web pages (8 from Julio and 12 from Hannah). At the other extreme, if both Julio and Hannah devote their 8 hours to cooking vegan meals, then the economy can produce 24 meals (16 from Julio and 8 from Hannah). These two points, which represent specialization of their two-person economy in one good, are indicated by point A and point D in Figure 6.5.6 "Julio and Hannah’s Joint Production Possibilities Frontier".

Julio and Hannah’s joint production possibilities frontier.

To fill in the rest of their joint production possibilities frontier, start from the vertical intercept, where 20 web pages are being produced. Suppose Julio and Hannah jointly decide that they would prefer to give up 1 web page to have some vegan meals. If Hannah were to produce only 11 web pages, she could free up 2/3 of an hour for vegan meals. She would produce 2/3 of a meal. Conversely, if Julio produced 1 fewer web page, that would free an hour of his time (because he is less efficient than Hannah at web design), and he could create 2 vegan meals. Evidently, it makes much more sense for Julio to shift from web design to cooking (see point B in Figure 6.5.6 "Julio and Hannah’s Joint Production Possibilities Frontier").

The most efficient way to substitute web design production for vegan meals production, starting at point A, is to have Julio switch from producing web pages to producing vegan meals. Julio should switch because he has a comparative advantage in cooking. As we move along the production possibilities frontier from point A to point B to point C, Julio continues to substitute from web pages to meals. For this segment, the slope of the production possibilities frontier is −1/2, which is Julio’s opportunity cost of web pages.

At point C, both individuals are completely specialized. Julio spends all 8 hours on vegan meals and produces 16 meals. Hannah spends all 8 hours on web design and produces 12 web pages. If they would like to have still more vegan meals, it is necessary for Hannah to start producing that service. Because she is less efficient at cooking and more efficient at web design than Julio, the cost of extra vegan meals increases. Between point A and point C, the cost of vegan meals was 1/2 a webpage. Between point C and point D, the cost of a unit of vegan meals is 1.5 web pages. The production possibilities frontier becomes much steeper. If you look carefully at Figure 6.5.4 "Julio’s Allocation of Time to Cooking Meals and Producing Web Pages", Figure 6.5.5 "Hannah’s Production Possibilities Frontier", and Figure 6.5.6 "Julio and Hannah’s Joint Production Possibilities Frontier", the joint production possibilities frontier is composed of the two individual frontiers joined together at point C.

Gains from Trade Once Again

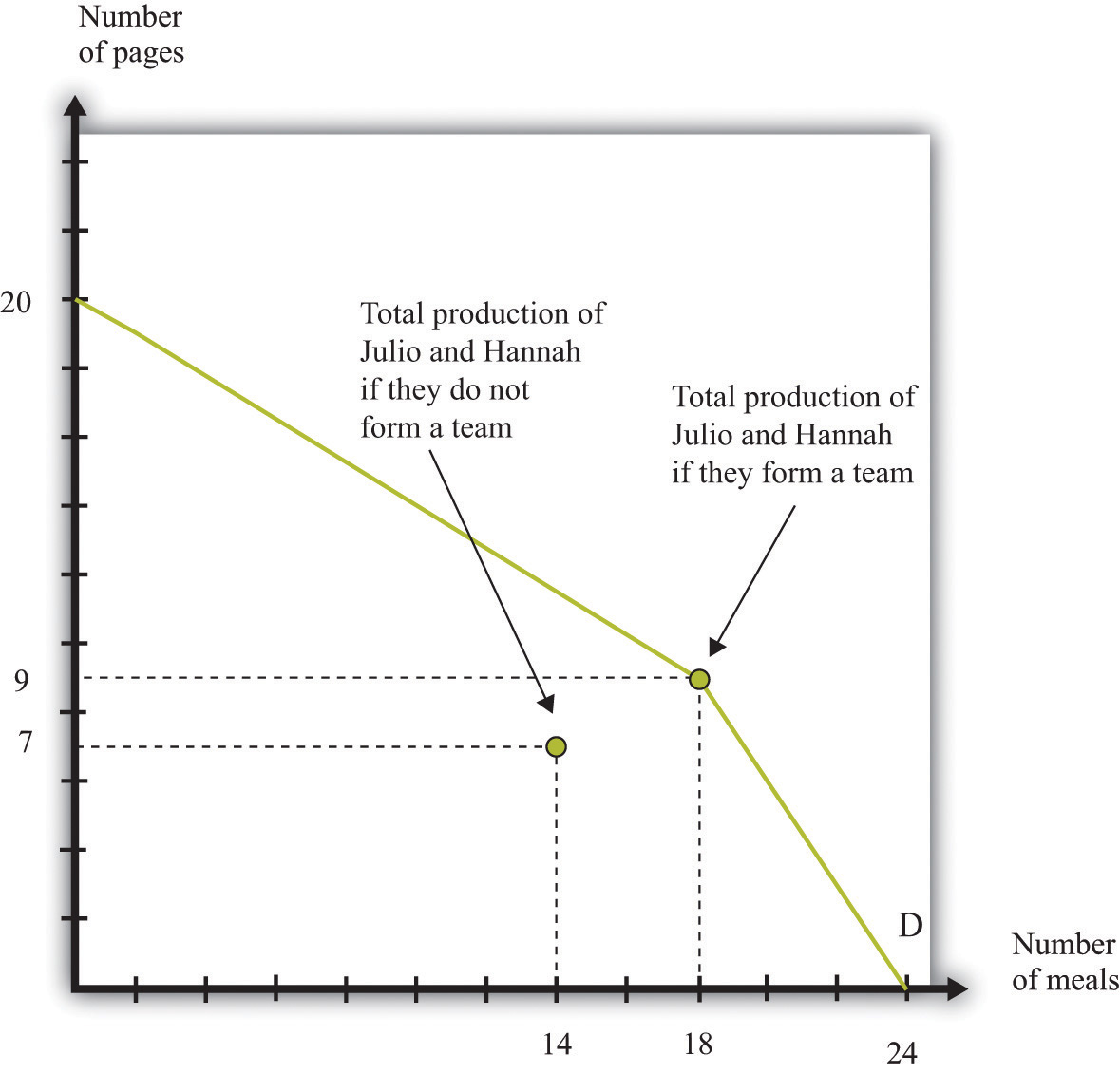

Figure 6.5.7 "Julio and Hannah’s Preferred Point" again shows the production possibilities frontier for the Julio-Hannah team: all the combinations of web pages and vegan meals that they can produce in one day, using the technologies available to them.

Julio and Hannah can benefit from joining forces.

Julio and Hannah have a great deal to gain by joining forces. We know that Julio, acting alone, produces 4 web pages and 8 vegan meals. Hannah, acting alone, produces 3 web pages and 6 vegan meals. The joint total is 7 web pages and 14 vegan meals. In Figure 6.5.7 "Julio and Hannah’s Preferred Point", we have labeled this as “Total production of Julio and Hannah if they do not form a team.” But look at what they can achieve if they work together: they can produce 9 web pages and 18 vegan meals.

Evidently they both can be better off when they work together. For example, each could get an additional web page and 2 vegan meals. Julio could have 5 web pages and 10 vegan meals (instead of 4 and 8, respectively), and Hannah could have 4 web pages and 8 vegan meals (instead of 3 and 6, respectively).

How do they do this? Julio specializes completely in vegan meals. He spends all 8 hours of his day cooking, producing 16 vegan meals. Hannah, meanwhile, gets to spend most of her time doing what she does best: designing web pages. She spends 6 hours on web design, producing 9 web pages, and 2 hours cooking, producing 2 vegan meals.

The key to this improvement is that we are no longer requiring that Julio and Hannah consume only what they can individually produce. Instead, they can produce according to their comparative advantage. They each specialize in the production of the good that they produce best and then trade to get a consumption bundle that they are happy with. The gains from trade come from the ability to specialize.

It is exactly such gains from trade that people are looking for when they place advertisements on craigslist. For example, the first ad we quoted was from someone with a comparative advantage in fixing furniture looking to trade with someone who had a comparative advantage in dental work. Comparative advantage is one of the most fundamental reasons why people trade, and sites like craigslist allow people to benefit from trade. Of course, in modern economies, most trade does not occur through individual barter; stores, wholesalers, and other intermediaries mediate trade. Although there are many mechanisms for trade, comparative advantage is a key motivation for trade.

Specialization and the History of the World

Economics famously teaches us that there is no such thing as a free lunch: everything has an opportunity cost. Paradoxically, economics also teaches us the secret of how we can make everyone better off than before simply by allowing them to trade—and if that isn’t a free lunch, then what is?

This idea is also the story of why the world is so much richer today than it was 100 years, 1,000 years, or 10,000 years ago. The ability to specialize and trade is a key to prosperity. In the modern world, almost everybody is highly specialized in their production, carrying out a very small number of very narrow tasks. Specialization permits people to become skilled and efficient workers. (This is true, by the way, even if people have similar innate abilities. People with identical abilities will still usually be more efficient at producing one good rather than two.) Trade means that even though people specialize in production, they can still generalize in consumption. At least in the developed world, we enjoy lives of luxury that were unimaginable even a couple of centuries ago. This luxury would be impossible without the ability to specialize and trade.

The story of Julio and Hannah is therefore much more than a textbook exercise. One of the first steps on the ladder of human progress was the shift from a world where people looked after themselves to a world where people started producing in hunter-gatherer teams. Humans figured out that they could be more productive if some people hunted and others gathered. They also started to learn the benefits of team production—hunting was more efficient if a group of hunters worked together, encircling the prey so it could not escape. Such hunting teams are perhaps the first example of something that looks like a firm: a group of individuals engaged jointly in production.

Production Possibilities Frontier for a Country

Before we finish with this story, let us try to get a sense of how we can expand it to an entire economy. We begin by adding a third individual to our story: Sergio. Sergio is less efficient than both Julio and Hannah. He has no absolute advantage in anything; he is no better at web design than Hannah, and he is no better preparing vegan meals than Julio. Remarkably, Julio and Hannah will still want to trade with him.

| Vegan Meals per Hour | Web Pages per Hour | Opportunity Cost of Web Pages (in Vegan Meals) | Opportunity Cost of Vegan Meals (in Web Pages) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Julio | 2 | 1 | 1/2 | 2 |

| Hannah | 1 | 1.5 | 3/2 | 2/3 |

| Sergio | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Table \(\PageIndex{4}\): Production Possibilities for Julio, Hannah, and Sergio

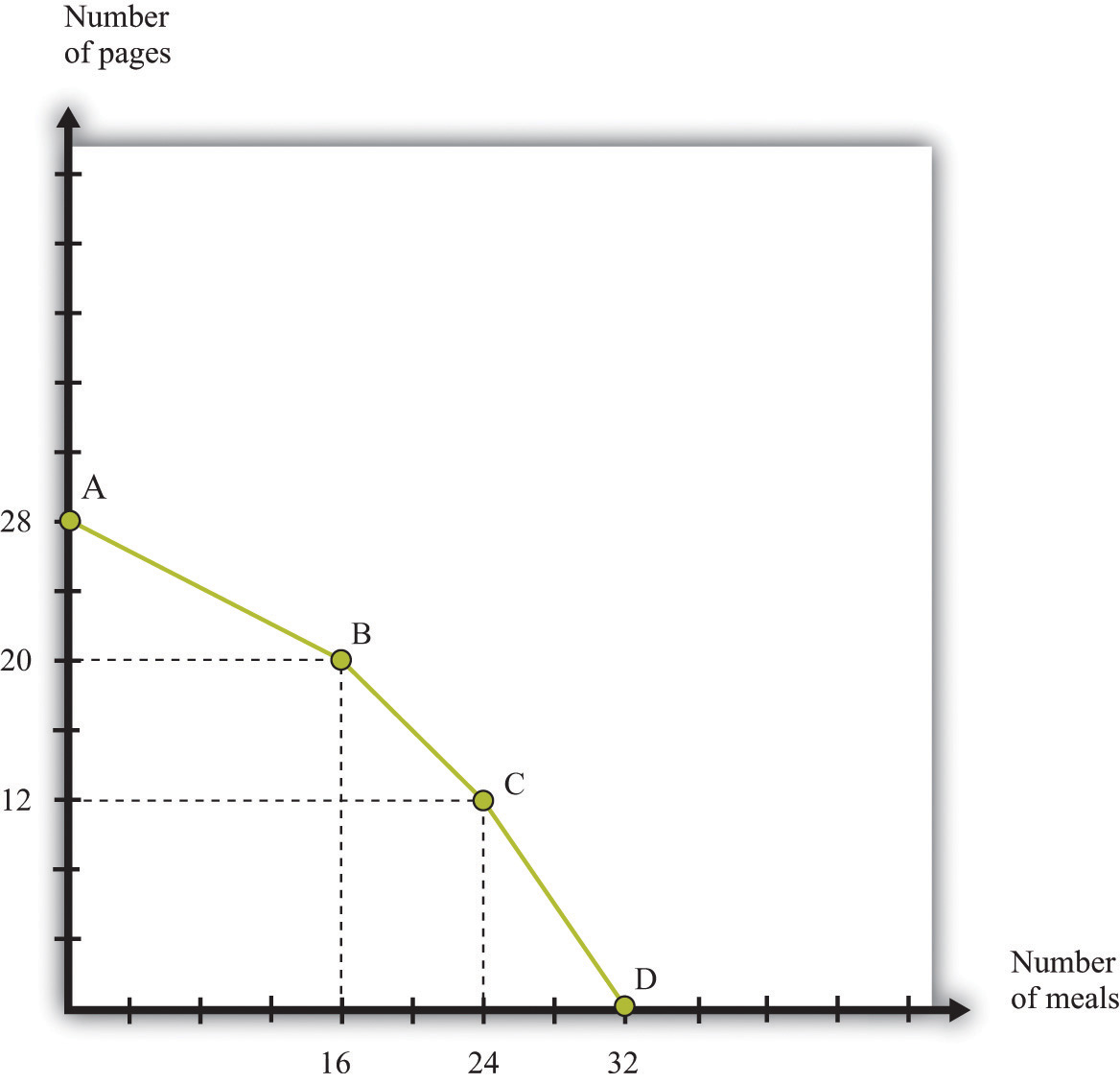

We begin by constructing the production possibilities frontier for these three individuals. The logic is the same as before. Start from the position where the economy produces nothing but web pages (see Figure 6.5.8 "The Production Possibilities Frontier with Three People", point A). Together, Julio, Hannah, and Sergio can produce a total of 28 web pages in a day. Then we first shift Julio to cooking because he has the lowest opportunity cost of that activity. As before, the slope of this first part of the frontier is −1/2, up to point B. At point B, Julio is producing nothing but vegan meals, and Hannah and Sergio are devoting all of their time to producing web pages. At point B, the economy produces 20 web pages and 16 vegan meals.

Here we show a production possibilities frontier with three individuals. Notice that it is smoother than the production possibilities frontier for two people.

If they want more vegan meals, who should switch next? The answer is Sergio because his opportunity cost of vegan meals is lower than Hannah’s. As Sergio starts shifting from web design to vegan meals, the frontier has slope −1, and we move from point B to point C. At point C, Sergio and Julio cook meals, and Hannah produces web pages. The number of web pages produced is 12, and there are 24 vegan meals. Finally, the last segment of the frontier has slope −3/2, as Hannah also shifts from web design to vegan meals. At point D, they all cook, with total production equal to 32 meals.

Let us suppose that Sergio, like the others, consumes in the ratio of 2 vegan meals for every web page. If the economy is at point C, the economy can produce 12 web pages and 24 vegan meals. Earlier, we saw that Hannah and Julio could together produce 9 web pages and 18 vegan meals, so bringing in Sergio allows for an extra 3 web pages and 6 vegan meals, which is more than Sergio could produce on his own. Even though Sergio is less efficient than both Julio and Hannah, there are still some gains from trade. The easiest way to see this is to note that it would take Sergio 9 hours to produce 3 web pages and 6 vegan meals. In 8 hours he could produce almost 3 web pages and over 5 vegan meals.

Where do the gains from trade come from? They come from the fact that, relative to Hannah, Sergio has a comparative advantage in vegan meals. Previously, Hannah was devoting some of her time to vegan meals, which meant she had to divert time from web design. This was costly because she is good at web design. By letting Sergio do the vegan meals, Hannah can specialize in what she does best. The end result is that there are extra web pages and vegan meals for them all to share.

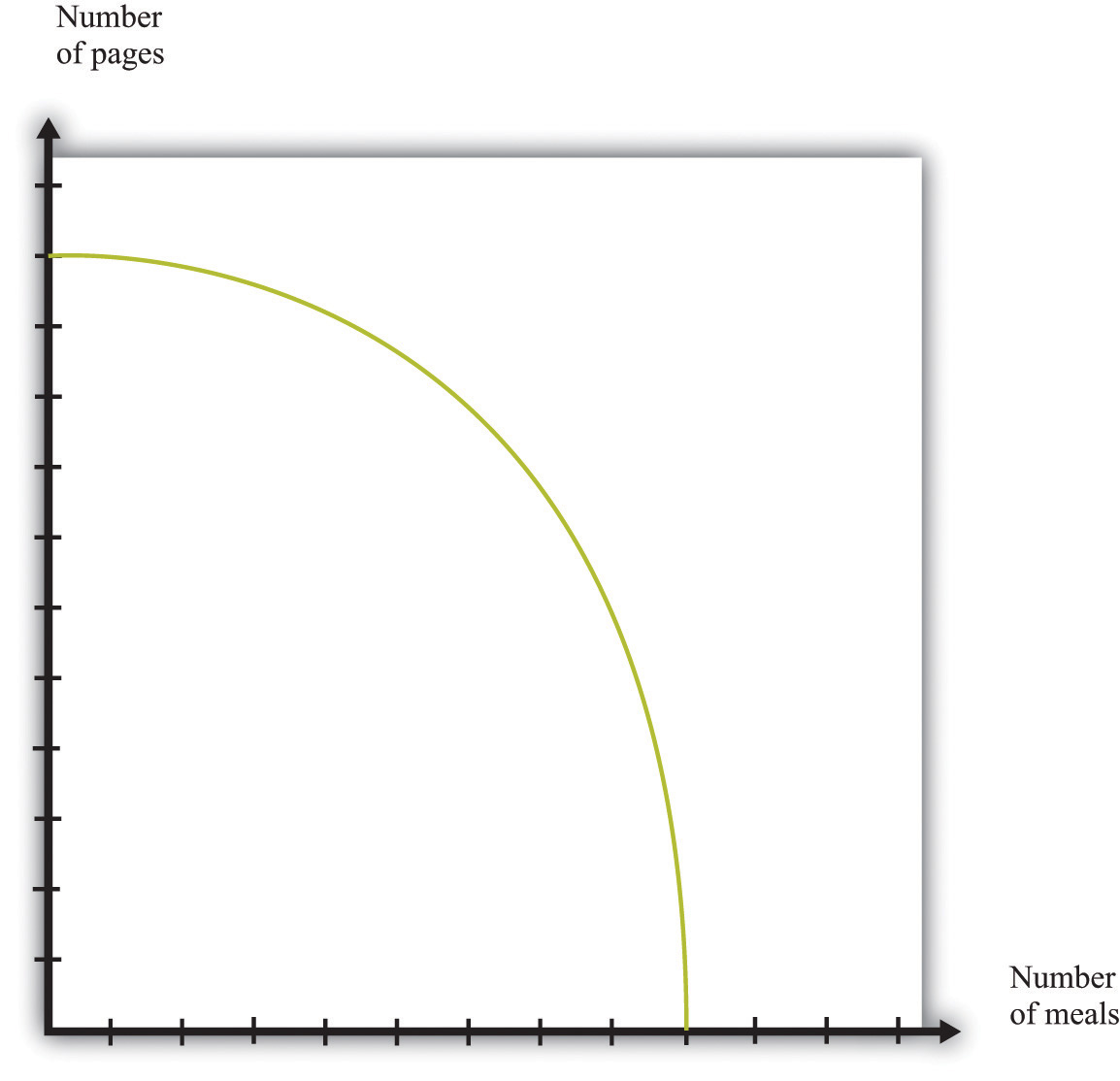

Comparing Figure 6.5.7 "Julio and Hannah’s Preferred Point" and Figure 6.5.8 "The Production Possibilities Frontier with Three People", you can see that the frontier becomes “smoother” when we add Sergio to the picture. Now imagine that we add more and more people to the economy, each with different technologies, and then construct the frontier in the same way. We would get a smoother and smoother production possibilities frontier. In the end, we might end up with something like Figure 6.5.9 "The Production Possibilities Frontier with a Large Number of People".

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): The Production Possibilities Frontier with a Large Number of People

As we add more and more people to the economy, the production possibilities frontier will become smoother.

It is easy enough to imagine that Julio, Hannah, and Sergio could all get together, agree to produce according to the principle of comparative advantage, and then share the goods that they have produced in a way that makes them all better off than they would be individually. Exactly how the goods would be shared would involve some kind of negotiation and bargaining among them. Once we imagine an economy with a large number of people in it, however, it is less clear how they would divide up the goods after they were produced. And that brings us full circle in the chapter. It is not enough that potential gains from trade exist. There must also be mechanisms, such as auctions and markets, that allow people to come together and realize these gains from trade.

Key Takeaways

- Gains in trade partly come from the fact that individuals specialize in production and generalize in consumption.

- The efficient way to organize production is by looking at comparative advantage.

- Gains to trade emerge when individuals produce according to comparative advantage and then trade goods and services with one another.

check your understanding

- Fill in the missing values in Table 6.5.2 "Julio’s Production Possibilities".