14.2: The Economics of Clean Air

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 45271

- Anonymous

- LibreTexts

Learning Objectives

- What is the Coase theorem?

- Why is the Coase theorem important?

- What is a social dilemma?

If we lived in a world where all economic transactions took place in competitive markets and in which there were “enough” markets, then we would obtain all the possible gains from trade. This logic falls down in reality because markets sometimes fail, for various reasons.

- Something prevents the economy from reaching the competitive outcome.

- Something prevents trade altogether, so the market is missing.

- Some people other than the buyer and seller are affected by the transaction.

We will get to Mexico City shortly. We begin, however, by thinking about a more isolated case of air pollution: cigarette smoke in an office.

Smokers, Nonsmokers, and the Coase Theorem

Cigarettes are sold and smoked almost everywhere. Yet in most countries around the world, you are not able to smoke when and where you please. Governments around the world place limitations on who can buy cigarettes, where they can be bought, and where they can be consumed. From an economic point of view, governments are deliberately restricting the ability of individuals to engage in voluntary transactions.There are many different ways in which governments intervene in market transactions. Chapter 12 "Barriers to Trade and the Underground Economy" contains more discussion. Why do governments restrict an individual’s ability to smoke where and when that person wants?

Mixed messages.

Our answer to this question begins by imagining two people who must share an office. One is a nonsmoker who dislikes the smell of cigarette smoke, while the other likes to smoke while working. On the way to work one day, the smoker purchases a pack of cigarettes that she plans to smoke at work. We can reasonably deduce from this that her valuation of these cigarettes is greater than the price she has to pay. She gets buyer surplus from the purchase. To be concrete, suppose a pack of 20 cigarettes costs $4 and her valuation of a pack of cigarettes is $10. Her surplus is then $6.

We can also reasonably assume that the seller’s cost is less than the price, otherwise he would not choose to make the sale. He gets seller surplus. For example, if his wholesale price for a pack of cigarettes is $2, then he earns $2 surplus (= $4 − $2) on every pack that he sells. The total surplus from the sale is the buyer surplus plus the seller surplus—that is, $8. So far so good.

The problems begin when the worker smokes her pack of cigarettes in the office. She obtains her $6 worth of enjoyment. However, a third party has now been affected by her decision to consume cigarettes: her office mate. The office mate dislikes the smell of smoke and may even face health risks from second-hand smoke. Thus even though the smoker and the store that sold the cigarettes are both better off, the office mate has been made worse off.

We should not automatically assume that the best thing is to ban smoking in the office just because the office mate is adversely affected. We need to know how much the nonsmoker is inconvenienced. Suppose the most the nonsmoker would be willing to pay for a smoke-free office is $2 per day. In this case, the $6 gain to the smoker exceeds the $2 loss to the nonsmoker. It seems like it should be easy enough for the two individuals to find a way for everyone to be happy. For example, imagine that the smoker agreed to pay the nonsmoker $4 a day for the right to smoke in the office. Both would then get $2 surplus per day.

On the other hand, suppose a smoke-free office is worth $10 per day to the nonsmoker. In this case, his valuation of clean air ($10) exceeds the smoker’s gain ($6). The smoker would be unwilling to pay the nonsmoker enough to compensate for dirtying the air in the office. It would be better not to allow smoking in the office.

We have assumed here that the default situation is that the office should be smoke-free. In the language of economics, the nonsmoker owns the property rights to the clean air in the office. Property rights over a resource mean that, by law, the owner can make all decisions regarding the use of the resource. Because of this, the smoker must pay the nonsmoker compensation if she wishes to be allowed to smoke in the office.

We could imagine the opposite situation, where the smoker starts off with the right to smoke in the office. Would we expect a different result from their negotiations? If the smoke-free office was worth only $2 to the nonsmoker, then he would not be willing to pay enough to persuade his office mate not to smoke: the most he would pay is $2, which is less than the smoker’s surplus. If, on the other hand, the nonsmoker valued the smoke-free office at $10, then he values a smoke-free office more than the smoker values smoking in the office. The nonsmoker could pay the smoker not to smoke. For example, imagine he pays her $8 per day to not smoke. He pays $8 for the clean air, which is worth $10 to him, so he gets $2 of surplus. The smoker receives $8, which exceeds the surplus she would get from smoking in the office. Again, they would both be happy.

Thus if the smoker “owns” the clean air, the nonsmoker must pay the smoker if he wants a smoke-free office. If the nonsmoker has the property rights, it is the smoker who must pay. In either case, the basic outcome will be the same: there will be smoking in the office if the smoker’s valuation exceeds the nonsmoker’s valuation; there will be no smoking if the nonsmoker’s valuation exceeds the smoker’s valuation. But the property rights are valuable. It is the owner of the property rights—whoever that may be—who gets compensation from the other.

As long as they know who has the property rights, it seems likely that the two individuals will be able to come to an agreement that benefits them both. You might imagine, though, that they would find it far harder to come to an agreement if it was ambiguous who had the property rights in the first place. The smoker would likely claim the right to smoke in the office, while the nonsmoker would assert his right to clean air. If they could not settle this basic question, it is unlikely that they would be able to reach a more complicated agreement involving compensation payments.

Let us imagine a further twist. Suppose the nonsmoker has property rights but values clean air at only $7 per day. This is still greater than the smoker’s surplus, so, as before, we expect that they would agree to a smoke-free office. But the nonsmoker’s valuation for clean air is less than the total surplus of the smoker and the store that sold her the cigarettes (recall that the smoker gets $6 surplus and the store gets $2 surplus). If the storekeeper, the smoker, and the nonsmoker all got together, they should again be able to find an arrangement that benefits everyone. For example, the storekeeper and the smoker could jointly give the nonsmoker $7 and still have $1 of surplus to bargain over.

It seems perfectly reasonable to imagine that two people who share an office could come to a mutually beneficial agreement about smoking in the office. It seems much more far-fetched, though, to imagine that they would come to an agreement together with the storekeeper who sold the cigarettes. Economists say that the difference between the two cases is due to transaction costs—the costs of making and enforcing agreements.

We began this section by observing that a transaction may affect not only the buyer and the seller but also third parties. When this is the case, we cannot be sure that trade benefits everyone. Even if the buyer and the seller are both made better off, third parties may be made worse off. However, if property rights are clearly established and transaction costs are low, then we can expect that private negotiations could solve these problems. This idea was first articulated by the Nobel prize–winning economist Ronald Coase ( http://www.coase.org) and is called the Coase theorem: if property rights are clearly established and transaction costs are low, private bargaining will lead to efficient outcomes.

It is notable that in reality, we do not see office workers buying and selling the right to smoke in an office. Instead, blanket bans on smoking have been enacted throughout the United States and in many other countries throughout the world. Why do we get this government response? One argument for these bans is that smoking poses health risks. In this case, antismoking campaigns are based on an idea that individuals are not always capable of making good choices for themselves. Chapter 5 "Life Decisions" has more to say about whether individuals are good judges of their own actions, particularly when making decisions with long-term consequences. But another reason is a recognition of the transaction costs involved in these private negotiations. Even if you think two coworkers could reach an agreement, imagine an office with 10 people—perhaps there are 3 smokers and 7 nonsmokers—all of whom place a different valuation on clean air in the office. If we knew everybody’s true valuations, then in theory it would be possible to create a system of payments that made everybody better off. In practice, however, people might lie about their valuations. Finding the right system of payments would be very hard indeed and would take a lot of time and effort.

Perhaps you can now see the parallel with Mexico City. The major pollution problem is the emissions from the cars that people drive. Individual residents of Mexico City make decisions to buy gasoline and drive. These transactions create value for the drivers and the sellers of gasoline—but third parties are adversely affected. The Coase theorem can work when the parties involved are easily identifiable and small in number. In contrast, it is impossible to imagine the 20 million residents of Mexico City all meeting and coming to some kind of private agreement to limit their collective driving behavior.

Social Dilemma

Air pollution and second-hand smoke have a common structure, which we explain in this section. Once you understand these common elements, you will probably be able to think of many other examples. We show the interactions between an individual and the rest of society in Table 14.2.1 "The Payoffs in a Social Dilemma Game". This is called a social dilemma game.

| Everyone Else Drives (Air Is Polluted) | Everyone Else Takes Public Transportation (Air Is Clean) | |

|---|---|---|

| You Drive | $0 | $2 |

| You Take Public Transportation | −$1 | $1 |

| Regardless of which action you choose, your payoffs are higher if everybody else takes public transportation ($2 > $0; $1 > −$1). Regardless of the actions of others, your payoffs are always higher if you drive ($0 > −$1; $2 > $0). | ||

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\): The Payoffs in a Social Dilemma Game

In Mexico City, it is very possible that people would agree that they would prefer a situation where everybody drives less. Yet this is not what happens. To see why, look at Table 14.2.1 "The Payoffs in a Social Dilemma Game" and imagine you are a car owner in Mexico City. You have to decide how to get to work—by driving or taking public transportation. There are two rows in the table. One is labeled “You Drive,” and the other is labeled “You Take Public Transportation.” The rows represent your possible choices. The columns refer to everybody else’s choices. Everyone else who owns a car similarly chooses between driving and taking public transportation. To keep things simple, we suppose that everyone else makes the same choice. If everybody chooses to drive, then the air is polluted. If everybody chooses to take public transportation, then the air is clean. The current situation in Mexico City is that you and all other car owners are driving to work. You enjoy the convenience of driving rather than taking public transportation, but you suffer from the polluted air.

The numbers in the table refer to your payoffs from the different possible combinations. As in our smoking example, we can think of these as the valuations per day that you place on different outcomes. What matters is how these different possibilities compare with the status quo, where you and everyone else drive. We therefore begin by setting your payoff at the status quo (the number in the top left cell) at $0. Suppose also that the following are true.

- You value clean air rather than dirty air at $2 per day—that is, you would be willing to pay $2 per day to have clean air rather than dirty air.

- After taking into account the relative costs and inconveniences of driving versus public transportation, you value driving compared to public transportation at $1 per day—that is, you would need to be compensated $1 per day to make you just as happy to take public transportation rather than drive.

Based on these conditions, we can calculate the payoffs in the other three cells of the table:

- The top right cell is the case where you drive and everyone else takes public transportation. Compared to the status quo, you are better off because you get to enjoy clean air. This is worth $2 to you, so your payoff is $2.

- The bottom left cell is the case where you take public transportation and everyone else drives. You still have to breathe polluted air, and you no longer get the convenience of driving (which is worth $1). Compared to the status quo, you are worse off. Your payoff is −$1.

- The bottom right cell combines the two previous cases. In this case, you and everyone else take public transportation. You get the benefit of clean air (worth $2), but you lose the benefit of driving (worth $1). Your payoff is \($2 − $1 = $1\).

What would you do in this situation? Suppose you think that everyone else is going to drive. You are better off if you drive (payoff is $0) rather than take public transportation (payoff is −$1). What if everyone else takes public transportation? Then you still prefer to drive (payoff is $2) rather than take public transportation (payoff is $1). We conclude you will drive regardless of what others in society choose to do.

Here is the crux of the problem: the situation looks the same to everybody else as it does to you. As you evaluate these relative payoffs and choose to drive, so too does everyone else. We therefore expect that everyone will follow their individual incentives and choose to drive. We end up in the top left cell, where your payoff is $0.

What is striking, though, is that you would prefer the outcome where everybody—including you—uses public transportation. Your payoff in the bottom right cell is $1, which is better than the current situation. Everyone else would prefer this outcome as well. Society ends up in a bad situation, with everybody driving, even though everyone agrees that there is a better option out there. This is the essence of the social dilemma.

You are one of many people. Although you may value clean air, you are powerless as an individual to keep it clean. And because you are only one person, your decision has a tiny effect on the overall quality of the air. Thus you choose to drive, without paying attention to your effect on the environment. But because everybody makes the same decision, the cumulative effect is that there is a lot of air pollution.

The social dilemma is also sometimes known as the “tragedy of the commons.” This refers to the time when cattle farmers had access to common grazing land. Because every farmer had the right to graze his cattle on this land, no one was in a position to ensure that the land was well managed. Every farmer paid attention only to the health of his own cattle and did not worry about the effect of his cattle on the overall quality of the grazing land. Because every farmer made the same decision, the result was overgrazing, which destroyed the land for everyone.

How do we solve problems such as this? To avoid the bad outcome of the social dilemma, we must find some way of changing the payoffs of the game. We have already seen that, if transaction costs are low, people may be able to negotiate privately. In the case of Mexico City smog, however, such negotiation is impractical. In this case, one possible solution is for the government to alter the payoffs. For example, in the run-up to the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, the Chinese government wanted to improve air quality in the city. It therefore allowed cars to drive in the city only every other day (whether a car was permitted on a given day depended on whether the last digit of the license number was odd or even). If you tried to drive on the wrong day, you might have to pay a large fine, so the payoff to driving changed. We have more to say about government policy later in the chapter.

Toolkit: Section 31.18 "Nash Equilibrium"

You can review the social dilemma and other games in the toolkit.

Private Benefits and Social Costs

When people face a social dilemma, the actions that are the best for all individuals lead to an outcome that is bad for everyone. Much of the rest of the chapter addresses why this happens.

We begin by remembering our theory of how people make consumption choices. In general, people consume a good up to the point where their marginal valuation from the last unit of that good equals the price of that unit. This is a specific statement of a more general principle for decision making: “consume until marginal benefit equals marginal cost.”

In the social dilemma of Table 14.2.1 "The Payoffs in a Social Dilemma Game", you had two choices: driving or not driving. Let us now expand that to think about a situation where you are deciding how much to drive. Driving your own car brings private benefits (that is, benefits that are obtained only by you), such as comfort and convenience. Driving also brings private costs, such as the costs of gasoline and maintenance of your vehicle. If this were all that was going on, there would be no problem: you would drive up to the point where your marginal (private) benefit from driving was equal to your marginal (private) cost of driving.

When you drive, though, you also impose costs on other people. Your decision to drive one more mile has a marginal social cost as well as a marginal private cost. Marginal social cost is the cost to society of consuming or producing one more unit of a good or a service. By “society,” we simply mean “you and everybody else.”

When you choose to drive your car, you contribute to air pollution. This is a cost to the rest of society. However, you have no incentive to worry about this. You care only about the extra cost to you. The same is true when the smoker smokes one more cigarette in the office: She imposes a cost on her office mate, but—unless they make an agreement otherwise—she does not pay this cost. She takes into account the marginal private cost to her (that is, how much she must pay for one more cigarette), but she ignores the cost to other people.

Ignoring for a moment some tricky questions about how to measure the cost of your actions to society, we can set out a principle for how much you should consume if your concern were the overall well-being of society: “consume until marginal benefit equals marginal social cost.” The marginal social cost of your driving is the extra cost if you drive more. It is the cost both to you and the cost that you impose on others in society. There can be many components to this cost. One component is the marginal private cost to you. In addition, you pollute the air, contributing to public health problems. You add greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, contributing to the risks of climate change. You make the roads more congested, thus wasting the time of other drivers on the roads. You cause wear and tear on the roads, which will ultimately be paid for by taxes on all drivers.

You might be puzzled at this point. If you drive one extra mile, does that really have any appreciable cost on society? The extra emissions from your driving obviously have a tiny effect on pollution and greenhouse gases. The wear and tear you impose on the roads is minimal. How can these minuscule effects possibly matter? The first and more obvious answer to this question is that the quality of the atmosphere and the roads is affected by everybody’s decisions—not only yours. Hundreds of thousands of cars around the world are polluting the atmosphere and damaging the roads. The second, more subtle, answer is that though your individual influence on air and road quality is very small, you are affecting a very large number of people. If you drive an extra mile in Mexico City, you are affecting the air that is breathed by 20 million people. The marginal social cost of your driving includes the effect on every single one of these people. Likewise, one more mile of driving may add only a tiny amount to the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, but that tiny effect must be added up over the entire population of the world.

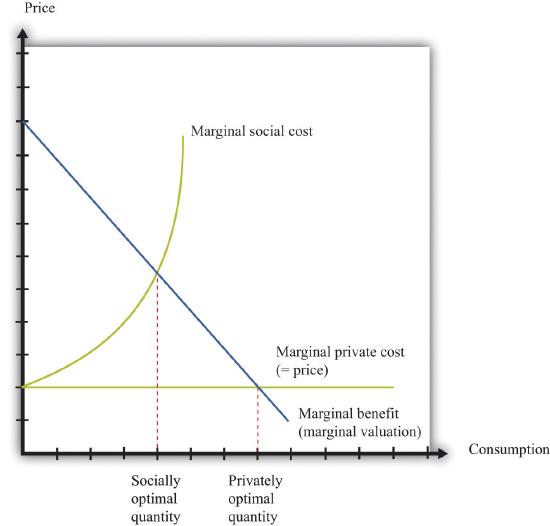

As a result, the marginal social cost of your driving is greater than your marginal private cost. Figure 14.2.1 "A Divergence between Marginal Private Cost and Marginal Social Cost" shows the implications of this. Think of consumption in this diagram as referring to the amount of driving you do. The marginal private cost of your driving is the cost of fuel, depreciation of your car, and so on. But the marginal social cost also includes the pollution of the air and the congestion of the roads. Because the marginal social cost is greater than the marginal (private) cost, you will drive too much, from the perspective of society as a whole. This is exactly what we saw in the social dilemma. People choose to drive and pollute the air, even though all members of society could be happier if everyone were to take public transportation and generate less pollution.

The gap between private costs and social costs means that too much driving is undertaken, from the perspective of society as a whole. The outcome is inefficient because people only have an incentive to take account of the private costs of their actions.

Toolkit: Section 31.11 "Efficiency and Deadweight Loss"

You can review the concept of efficiency in the toolkit.

The gap between marginal private cost and marginal social cost is a measure of the impact that an individual has on the rest of society.

Figure 14.2.1 "A Divergence between Marginal Private Cost and Marginal Social Cost" also illustrates another point. Economic analysis tells us that there is “too much” pollution, from a social point of view. This observation probably comes as no surprise. Economic analysis also makes it clear, though, that it is possible to have too little pollution as well as too much. There is an optimal amount of driving for each individual, to be found where marginal social cost and marginal benefit are equal. At this amount of driving, there will be some pollution: the optimal amount of pollution for society as a whole. If we were to ban driving altogether, we would have less pollution, but we would also lose all the benefits from driving.

Our discussion here has been about decisions of consumers, but firms also are sources of pollution. Firms use trucks and other vehicles that, like cars, impose costs on the rest of society. Some firms pollute the air or the water. Exactly the same principles still apply. Any individual firm has no incentive to take into account the costs that it imposes on the rest of society. As a result, firms pollute too much from a social point of view.

Key Takeaways

- The Coase theorem states that if property rights are well defined and transaction costs are low, then bargaining will lead to an efficient outcome.

- The Coase theorem provides the rationale for a market solution to pollution and other similar social problems.

- A social dilemma arises when there are many individuals each making choices that are in their self-interest but leading to an outcome that is bad for society.

Exercises

- Why does the Coase theorem require that transaction costs be low?

- Consider Table 14.2.1 "The Payoffs in a Social Dilemma Game". Suppose your payoff from taking public transportation when everyone else drives is −$2 rather than −$1. Would this change the basic message of this example?

- Look at Figure 14.2.1 "A Divergence between Marginal Private Cost and Marginal Social Cost". How would you modify this figure to make the difference between social and privately optimal quantities larger? Explain your reasoning.

- Suppose you are in the library and there are two people making out between the shelves. Describe this situation in terms of social versus private costs. How would you use the Coase theorem to find an efficient allocation?