1.4: What is Money?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 178591

The Definition of Money

Money is most often defined as “a medium of exchange with no intrinsic value.” This essentially means that what people accept as money can be used as money. If you go back in history, you will see that people have used a number of different things as money, some that had intrinsic value (such as gold and silver), and many that had no intrinsic value of their own (such as seashells and cocoa beans). Currently, all countries around the world use money that is known as fiat money. From Latin, this term means, “Let it be so.” Essentially, this means that each country prints money on paper (or in some cases, plastic), and that currency is not backed by anything of intrinsic value except the full faith and credit of a country’s Central Bank.

In the past, money was backed by silver (the silver standard) or gold (the gold standard). However, that came with its own set of problems. It meant that you had to have silver or gold equivalent in value to the amount of total money you had in circulation. This made it difficult to increase the supply of money in your economy, since you had to acquire enough silver or gold to back up the additional money you wanted to circulate. So the Central Banks of the world went off the “metal standard” for their currency. The U.S. abandoned the gold standard in 1933 but allowed holders of dollar currency to convert them to gold at the fixed price of $35 per ounce, an arrangement that was eliminated in 1971. The U.S. abandoned the silver standard in 1935.

So, in a way, all paper money is fake! It is, of course, backed by “the full faith and credit” of the country that issued it, but that’s the only thing backing it. That means that unstable countries might end up with currency that cannot be used as payment for oil or food. Even if it is accepted, it is only at a greatly depreciated value. The world’s currencies fluctuate relative to each other according to the rules of demand and supply. For example, if you are trying to understand the exchange rates between the U.S. dollar and the Euro, consider how many U.S. dollars it would take to buy one Euro. If a lot of people who own dollars want to buy Euros but not an equal amount of people who own Euros want to buy dollars, the Euro will appreciate relative to the dollar.

The Barter System

Some economies in the past did not use money; instead, they used the barter system. It is a simple system. Let’s say that I have two extra bushels of corn, and I need some wheat. I will swap you my two bushels of corn for two bushels of wheat.

The problem is that the barter system depends on what is called a coincidence of wants. Now let’s say that I have three extra pigs, and I ask my neighbor ask to trade them for a cow. However, he does not have any cows he wants to trade, and he does not want any more pigs. That means I have to go searching for someone who wants to trade a cow for my pigs. Money solves this problem, because cows and pigs (and everything that is for sale) can be valued in terms of money. Instead of bartering, I can sell my pigs in the local marketplace and then use that money to buy a cow.

How Money Is Used

Money is used in several ways:

- It is a medium of exchange. A medium of exchange is something that can be traded for goods and services. As we showed above, it solves the problem of the coincidence of wants.

- It is a store of value. Money’s function as a store of value allows you to hold on to money and buy something in the future, and the money is still accepted. If you are going to hold onto money, you should, of course, not hide it under your pillow, but put it in a savings account and earn some interest on it. When we save money for our future retirement, it is functioning as a store of value, and we must have confidence in the money still being valuable when we retire.

- It is a unit of account. Money functions as a universal yardstick that expresses the value of goods and services in a single measure. For example, your labor might be valued at $15 per hour and then you can take that money you earn and buy a dozen eggs at $1.98 per dozen.

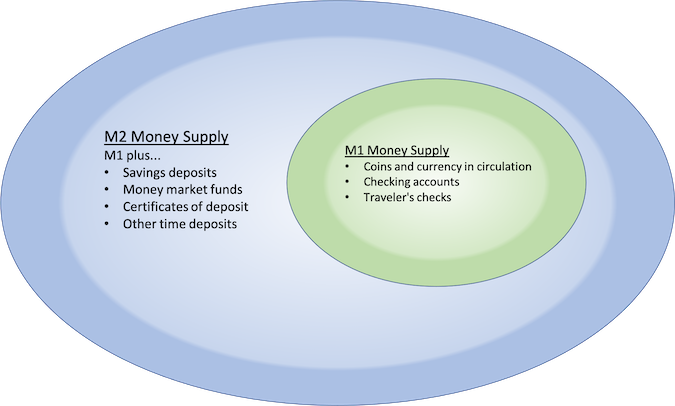

The Amount of Money in the U.S. (M2)

The Money Supply (M2) in 2019 is $14,941,700,000,000. This is a lot of money. According to the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, the types of money that are counted in the M2 are:

- Savings deposits (which include money market deposit accounts)

- Small-denomination time deposits (less than $100,000)

- Balances in retail money market mutual funds

Who Owns the Money

Technically, the monetary base (coins and paper currency) belongs to the Central Bank of the country that created it (in our case, The Federal Reserve Bank). If you look at a U.S. dollar, you should see a few important details.

First, at the top of the banknote, it says, “Federal Reserve Note.” A note is an I.O.U. or promissory note that you will repay a loan. In essence, this paper currency is a loan from the Federal Reserve Bank to the holder of the note. It also has the signatures of the Secretary of the Treasury and the Treasurer of the United States. Since a promissory note is a legal document, it must be signed. This I.O.U. is signed. Finally, the bill also states that “This note is legal tender for all debts, public and private.” The currency may be used to pay for goods and services and to satisfy all debt. Of course, when you are paid money for your work, you get to use the money, but the actual currency is on loan from the Federal Reserve Bank.

A lot of people do not realize that not only does the Federal Reserve Bank create money, but the actual banking system also creates money. When you deposit your money into a bank, whether it be currency or a paycheck, the bank credits your account electronically. If you deposit $1000, you can claim it back whenever you want. This is called a demand deposit. The bank then might lend out the $1,000 to someone else, and now there is $2,000 in the economy’s money supply. If the person deposits that loan of $1,000 in their own bank, that second bank can then lend it out, and now there is $3,000 in the M2. Pretty sneaky, huh? In aggregate terms, of the total 2019 M2, only about 10% is currency. The rest of M2 has been created electronically by the banking system.

The Federal Reserve Bank

The Federal Reserve Bank of the United States is the Central Bank of the United States. Virtually all countries have a Central Bank. The main exception to this is the European Union, which created a common currency, the Euro, in 1999. The EU has 27 members and 23 of them currently use the Euro as their official currency. As a result, the EU created the European Central Bank, which functions as the Central Bank for countries using the Euro. The key function of these Central Banks is threefold:

- It monitors the banks and other financial institutions in the country to make sure they are following its rules and are acting in a financially responsible manner. The Central Bank has great power in this area and can shut down banks, either on its own or (in the United States) through the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which guarantees all the deposits at U.S. banks.

- It controls key interest rates, such as rates for bank borrowings and, indirectly through the prime rate, commercial lines of credit for companies. It also indirectly influences longer term rates such as car loans and mortgages.

- It also controls the money supply.

These activities all together are called monetary policy. The Federal Reserve Bank (or “the Fed”) is made up of three key entities:

- The Federal Reserve Board of Governors. The seven governors are appointed by the President of the United States and serve for fourteen years each. Their terms are staggered so that one governor’s term expires every two years. This arrangement prevents one President from controlling the Fed through their appointments. The Chair of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors is also appointed every four years by the President.

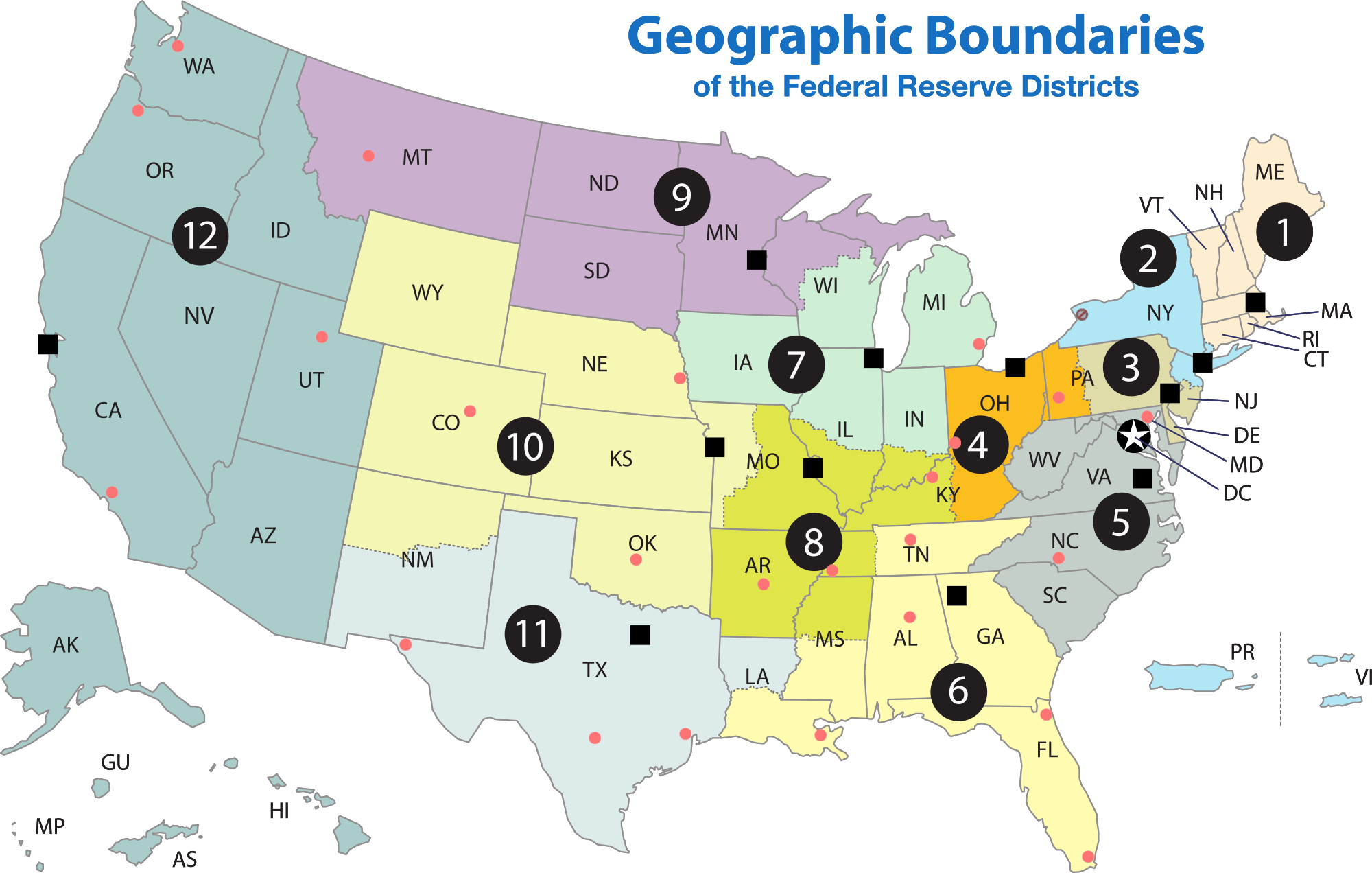

- The Federal Reserve Banks. There are twelve Federal Reserve Banks in the United States and these are effectively local offices of the Fed. The United States is divided into twelve Federal Reserve Districts, with a Federal Reserve Bank monitoring the commercial banks in each district and each Federal Reserve Bank is headed by a President.

Figure 4.2. Federal Reserve Districts Map – Banks & Branches by ChrisnHouston is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 License. - The Open Market Committee. The Open Market Committee dictates monetary policy. It has twelve members and is composed of the seven members of the Board of Governors, the President of the New York District Federal Reserve Bank , and four additional Presidents of the District Federal Reserve Banks, each of whom serves on a rotating basis for one year. The Open Market Committee meets every six weeks to decide on monetary policy. In addition to the function and structure of the Fed, we also need to understand the mandate of the Fed. According to the various laws creating and underpinning the Federal Reserve Bank, it has a dual mandate:

- To maintain low and predictable rates of inflation

- To maintain maximum levels of employment that are sustainable.

The Fed meets these mandates by controlling the amount of money in the economy. This indirectly influences the amount of goods and services bought in the economy.

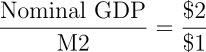

The total amount of goods and services made and purchased in any economy in a specific time period (usually a year) is called the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of an economy. If we look back over the last forty years of the U.S. economy, the empirical evidence tells us that the ratio of the GDP purchased each year to the M2 is pretty constant. Specifically, it is a ratio of approximately 2 to 1.

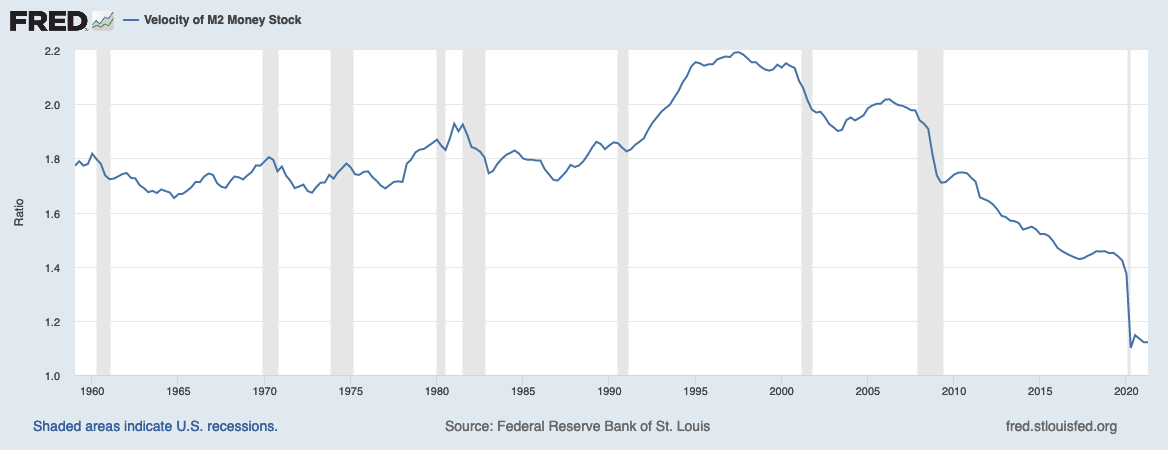

The technical term for this ratio is the Velocity of Circulation. The relatively constant Velocity of Circulation has three important implications for Monetary Policy. First, this constant 2 to 1 ratio means that every dollar of money in the economy buys two dollars of GDP over the course of a year. Second, it also means that if the Fed wants to influence the growth of GDP, it needs to create $1 of Money for every $2 of GDP it wants to stimulate. Third, the growth rate of M2 needs to be equal to the growth rate of GDP or the lack of money will slow down the growth of GDP. The relatively constant ratio of GDP to M2 is an important assumption of the Quantity Theory of Money, as espoused by the Monetarist economists. Monetarism is a school of thought in monetary economics that emphasizes the role of governments in controlling the amount of money in circulation. Monetarist theory asserts that variations in the money supply have major influences on national output in the short run and on price levels over longer periods (Wikipedia).

The standard bearer of Monetarism was Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman of the University of Chicago. Unfortunately, although the ratio of GDP to M2 was fairly constant in the 1960s and 1970s when Friedman was doing his Nobel Prize winning research, it is no longer true (see graph below). This discrepancy now calls into question the validity of Monetarism.

Firms need employees to make things and provide services, and we can get pretty specific about how many people will be employed based on additional GDP purchases. In 2018, if we take the total GDP and divide it by the number of employed people, we get this result:

.png)

Thus we see that for every $131,600 in GDP purchased throughout the course of the year, the economy needs to hire on average one additional worker. This is how the Federal Reserve Bank influences employment.

As for inflation, the Fed influences this by maintaining the growth of M2. Simply put, inflation is caused by too much money trying to buy fewer goods and services, thus raising prices. This can be expressed in the Inflation Equation from the economic Quantity Theory of Money:

.png)

.png)

Although this does not hold exactly for every year, it is true over the long run (ten years or more), and we see that the actual data support this relationship. An important way to interpret this equation (for our purposes) is that if the money supply is growing more quickly than the supply of goods and services available to purchase, then prices will rise. As we said, this general rise in the prices in an economy is called inflation. Therefore, we see that the Fed can influence employment by increasing the money supply or reduce the rate of inflation by decreasing the money supply. Unfortunately, these dual mandates are sometimes in conflict, and when they are, the Fed will always choose controlling inflation overachieving maximum employment. In the past, the Fed has sometimes put the economy into a recession in order to control inflation.

The Fed is very interested in controlling expectations in the marketplace, and it has been very clear about its targets for maximum employment and low and stable prices. The Fed is trying to achieve the natural rate of unemployment. The determination of this rate is an empirical question, not a theoretical one. The natural rate of unemployment is the rate which if we go below it wages generally rise (wage inflation), and this then causes general inflation in the economy. The Fed used to think the natural rate of inflation was 4.5%, but at the end 2019, the unemployment rate is 3.7% without seeing any significant inflation in the economy.

As to the ideal inflation rate, the Fed set a target of a 2% general rise in prices over the course of a year. We might call this target Goldilocks inflation, as the Fed does not want the rate of inflation to be much higher or much lower than this. Higher inflation can feed on itself (through inflation expectations), while lower inflation can cause consumers to hold off their spending. I should note that the Fed targets core inflation, which is the rise in GDP prices, and it eliminates food and energy prices from the calculation, as they are too volatile.

In order to control the money supply and therefore short term interest rates, the Fed conducts Open Market Operations. If unemployment is too high, the Fed buys Treasury Bonds from the banks, thereby increasing their Reserves (the banks’ money that has not yet been lent out). This increases the money supply and lowers interest rates, stimulating the economy through the availability of cheaper borrowing rates for all loans. If inflation is too high the Fed sells Treasury Bonds to the banks, thereby decreasing their Reserves. This decreases the money supply and increases interest rates and slows down the economy due to more expensive borrowing rates.

Nominal Money and Real Money

This subtitle might confuse you. What is the difference between nominal and real money? Further, what is the distinction between nominal and real wages? Simply put, nominal value is money’s face value. If you have a hundred-dollar bill, its nominal value is $100. On the other hand, its real value is what it can purchase. Let’s say you hold that $100 bill for a year, and in that year, prices of the things you normally buy rise by 10% (as measured by the Consumer Price Index, or CPI). Your $100 bill is now worth 10% less or $90 in real money. This is why high inflation is so pernicious; it erodes the value of your money. High inflation hurts poor people the most, because the things that usually inflate—food and energy—occupy a large portion of their budget. High inflation also hurts retired people on a fixed pension for the same reason. (As a side note, social security payments are increased every year according to the rise in the CPI, but many corporate pensions are not).

Nominal wages are the face value of the wages you receive, and similar to our discussion of real money above, real wages are what your wages can purchase. High inflation erodes the value of your wages, and this has a deep impact on your day-to-day life. Pew Research shows that real wages have been flat for the last 30 years or so, noting that despite the strong labor market, wage growth has lagged expectations. In fact, despite some ups and downs over the past several decades, today’s real average wage (that is, the wage after accounting for inflation) has about the same purchasing power it did 40 years ago. And what wage gains there have been have mostly flowed to the highest-paid tier of workers (2018).

These relatively flat real wages have exacerbated both the income distribution and wealth distribution in the United States. The top 10% of income earners have gained an increasing share of total income, and this has also contributed to the top 10% owning an increasing share of the wealth in the United States.

Finally, it is worth noting that employers consider real wages in their hiring decisions. This is true both in economic theory and in their real-world decisions. An increase in wages above the CPI actually causes a drop in labor demand and vice versa. The fact that real wages have been stagnant for many years is good for employers but bad for workers.

Foreign Exchange Rates

As part of your financial education in a global economy, you should understand global exchange rates. When importers bring foreign goods into the United States, they will put them up for sale at U.S. dollar prices. However, the manufacturer in the foreign country wants to be paid in the local currency. As you see below, supply and demand affect the value of one currency in terms of another, and this influences the price of an imported good in the United States.

Here is an example:

| Price of Toyota in Japan | Exchange Rate | Price of Toyota in the U.S. |

|---|---|---|

| 1,000,000 Yen | 100 Yen/ U.S. $ | $10,000 U.S. |

| 1,000,000 Yen | 90 Yen/ U.S. $ | $11,111 U.S. |

| 1,000,000 Yen | 110 Yen/ U.S. $ | $9,090 U.S. |

Think of the exchange rate as the price of the foreign currency. Thus when the U.S. dollar can purchase 100 Yen, the 1,000,000 Yen price translates to 10,000 in U.S. dollars. If the U.S. dollar depreciates to 90 Yen/ U.S. dollar, the Toyota costs more in the U.S. If the U.S. dollar appreciates to 110 Yen/ U.S. dollar, the Toyota costs less in the U.S.

The bottom line is that a stronger U.S. dollar makes imports into the United States cheaper and incentivizes U.S. consumers to buy more imports. The contrary is also true: a weaker U.S. dollar makes foreign goods more expensive and discourages imports. Similarly, a weaker U.S. dollar makes U.S. exports cheaper and encourages foreign consumers to buy our goods. U.S. Presidents and Treasury Secretaries always say that they want a strong U.S. dollar, but secretly, they really do not. Overall, a weaker dollar is good for the U.S. economy.

The basic law of supply and demand causes fluctuations in the valuations of currencies relative to one another. Even with these fluctuations, there are a number of reasons someone who holds a foreign currency would want to trade them for U.S. dollars:

- To buy U.S. Exports. U.S. companies who are exporting goods and services to a foreign company want to be paid in U.S. dollars, so foreign importers must exchange their currency for U.S. dollars.

- To invest in U.S. Investments, such as the U.S. Stock Market, the U.S. Bond Market, U.S. Real Estate, or to buy a U.S. company. Investors from every country in the world invest in the U.S. Stock and Bond Markets. They are considered one of the most reliable investment markets in the world. Since the stocks and bonds in these markets must be paid for in U.S. dollars, anyone buying U.S. stocks or bonds (or U.S. Real Estate or U.S. companies) must exchange their currency for U.S. dollars.

- Speculation on the volatility in the value of currencies (or “hot money”). Currency values fluctuate every day relative to each other. Usually, these daily fluctuations are small. However, over a year or longer, there can be significant changes in the relative value of currencies, caused by supply and demand for particular currencies. For example, if an investor expects the U.S. dollar to appreciate 10% over time against the Japanese Yen, they can buy and hold dollars until the they rise against the Yen. Then, after converting the dollars back to Yen, the investor will earn 10% (minus any transaction costs).

For a real world example, the U.S. dollar appreciated 4.3% in 2018 and continued to appreciate in 2019 (measured against a basket of foreign currencies) due to an influx of foreign money into U.S. investments. Foreign stock and bond markets were not doing as well as their U.S. counterparts at the time, so foreign investors had to trade their currency for U.S. dollars in order to invest in American markets. The demand for U.S. dollars caused it to rise and as a consequence, foreign imports became cheaper, and the U.S. brought in more imports.

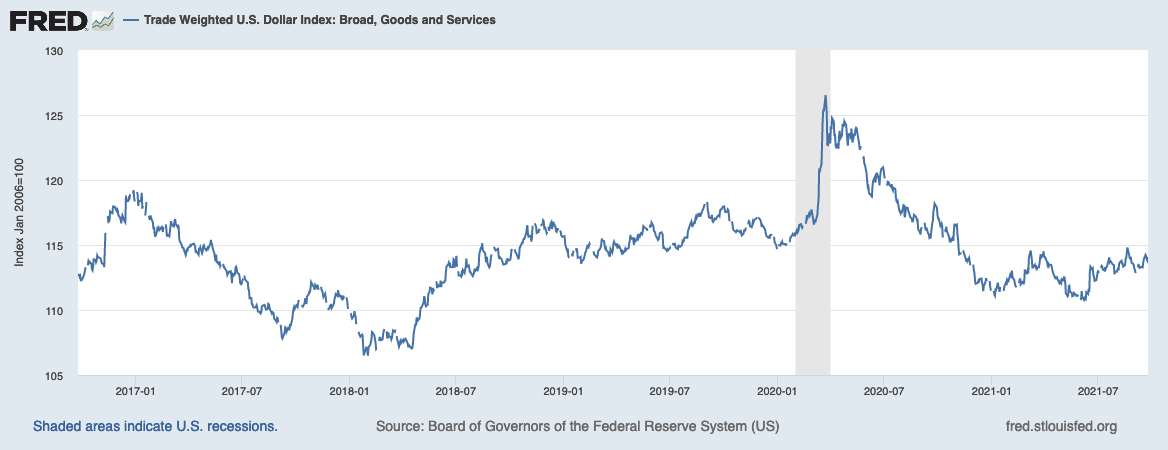

It’s all pretty complicated, but that’s the real world. Since 2019, the U.S. dollar has stopped its appreciation (after a brief jump during the Pandemic Recession), as seen in the graph below:

The U.S. dollar is also the preferred currency for several Central Banks, and it is the preferred international currency. As a result, the U.S. dollar is involved in over 90% of over $4 trillion dollars’ worth of foreign exchange trades every day.

How We Get Addicted to Money

In The Protestant Work Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism , sociologist Max Weber points out that there has been a predisposition to amassing material things since this country’s founding (1930). Puritans, the original colonizers were Calvinists, and as such, they believed in predestination. In this tradition, God already knows who is going to end up in heaven or hell; however, for Puritans, this also meant that those destined for heaven would also be blessed with material prosperity in this life. The Puritans then worked hard to attain material wealth but also led ascetic lifestyles—no drinking, no dancing, and no enjoyment of their wealth. As Weber points out, all of this was so that these forefathers of the American Dream could assure themselves that they were truly one of the chosen.

American materialism still exists in our society’s materialistic value orientation (MVO), as defined by Kasser and Kanner:

From our perspective, an MVO involves the belief that it is important to pursue the culturally sanctioned goals of attaining financial success, having nice possessions, having the right image (produced, in large part through consumer goods) and having a high status (defined mostly by the size of one’s pocketbook and the scope of one’s possessions (2004).

Further, Kasser and Kanner focus on two questions:

- What causes people to care about and to accept materialistic values and to “buy into” high consumption behavior?

MVO develops in individuals through two pathways:

-

- From personal experiences and environments that deny peoples’ basic psychological needs of safety, relatedness and love, and competence and autonomy

- From exposure to social models that encourage materialistic values – parents who are excessively materialistic or by heavy exposure to the advertisements and influences of our materialistic culture or by schooling (Kasser & Kanner, 2004)

-

- What are the personal, social and ecological consequences of an individual’s or a society’s having a strong MVO?

According to Kasser and Kanner, personal well-being declines as materialism becomes more centralized in someone’s value system. Further, they show that an MVO encourages behaviors that damage interpersonal and community relations and destroy the ecological health of the planet.

Many psychologists, economists, and neuroscientists have presented research that shows how easily money can become addictive (Layard, 2005, Peterson, 2007). The human brain constantly engages in what is called “hedonic adaptation.” When we reach a higher level of income, we initially derive satisfaction from it. However, very soon, we adapt mentally and emotionally to that higher level and need even more money to achieve the same level of happiness. Through the same mechanisms by which we can succumb to drugs, alcohol or gambling, people can become addicted to money.

Current psychological theories characterize money as both a tool (a function of money as what it can be exchanged for) and as a drug (a maladaptive function of money as an interest in the money itself) (Lea and Webley 2006). Essentially, this posits that people not only value money for its instrumentality—that is, how it enables people to achieve goals—but for itself— that is, for the totally false sense of control, security, and power that it gives (Vohs et al. 2006). Conversely, Price et al. (2002) have shown that physical and mental illness after financial strain due to job loss is triggered by reduced feelings of personal control.

Unfortunately, even with enormous amounts of money, the wealthy are no happier than the less wealthy. In fact, they are actually more prone to depression and psychopathology (Kasser & Kanner, 2004, p. 129). Adults who engage in conspicuous consumption are largely trying to compensate for our unique human awareness of mortality and the pursuit of self-worth and meaning that this engenders or, simply put, existential anxiety, or the fear of going out of existence (Kasser & Kanner, 2004, p.128). National and time-series studies attest to the fact that large amounts of wealth have little or no effect on happiness. Real purchasing power has more than doubled in the United States, France, and Japan over the last fifty years, but life satisfaction has not changed at all (Seligman, 2002, p. 153; Layard, 2005).

I believe that people with a MVO are at risk for anxiety, psychological problems, family dysfunctions, health problems, and personal financial problems. The evidence for this is voluminous (Kasser and Kanner 2004). These attitudes cause real damage and are then major contributors to social problems that undermine the fabric of our society. MVO even contributes to world discord, as the exportation of American materialism emphasizes the gulf between the haves and the have-nots around the globe.

Cryptocurrencies

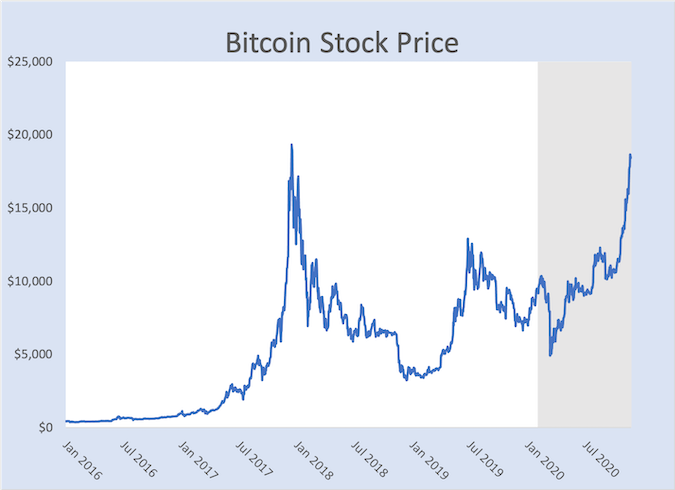

For economists, Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are an interesting experiment, but they are not yet ready to be adopted by banks and financial institutions as a way of doing business. The extreme volatility of Bitcoin (see chart below) and other cryptocurrencies make them an extremely poor store of value (one of the main functions of money) though they might be an adequate medium of exchange. Further, if you look at the history of the Bitcoin, you will see that there have been a number of scandals and thefts. Bitcoin’s defenders say these problems are just the “growing pains” of a whole new type of currency and system. To this I say, that is fine, but let me know when it is grown up and adopted by (and guaranteed by) major financial institutions in the United States. My advice is to stay away from these cryptocurrencies for now.

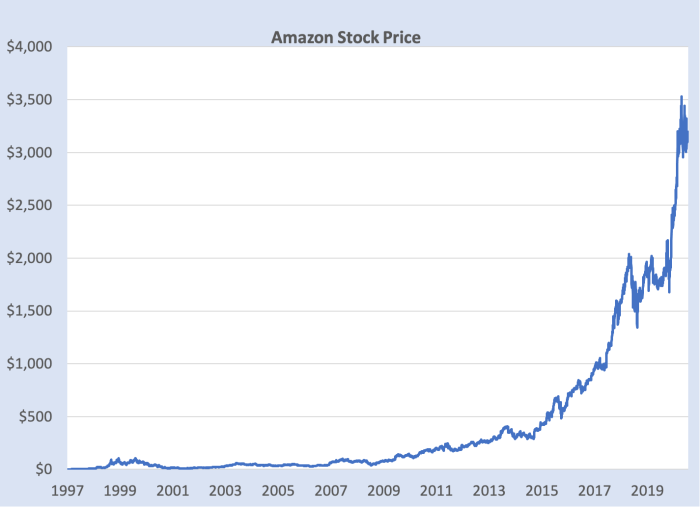

The graph below certainly looks enticing. If you had bought one Bitcoin on January 8, 2015, at a price of $288.99, you would have had your investment grow to $19,650 dollars by December 16, 2017, a return of 67 times your original investment, 3,350% per year for each of the two years you held it. But how could you have known that? At the same time, if you had bought one share of Amazon stock on January 1, 2015 at $320, you would have had your investment grow to $3,225 on August 6, 2020, a return of 10 times your original investment, an equivalent to 200% annual return on your investment for each of the five years you held it. The fundamental difference here is that Amazon makes something. It provides goods and services to customers, it has a cash flow, and it has revenue and net income on which you can calculate Return on Investment (the universal way we value companies and the price of their stocks). Buying Bitcoin is almost like buying collectibles, like an A-Rod rookie baseball card or a pair of original Air Jordans. Will these collectibles increase in value? Maybe yes or maybe no. Do you remember the Beanie Baby collecting craze? Did those increase in value?

“Risk follows reward” is an immutable law of Wall Street; if you are seeking higher than average returns, you must go after riskier investments. You might have been lucky enough to invest in Bitcoin in 2015, but you might have bought it in 2017, at the height of its speculative run. You also could have bought shares in an S&P mutual fund at the Vanguard Mutual Fund Company, and your return from January 2, 2015 to August 6, 2020, would have been + 63% over five and a half years for an annual return of 11.5%, with much less risk than Bitcoin (and the start-up, Amazon).

A Cashless Society

Unquestionably, we are moving more and more toward a cashless society. In a cashless society (in the U.S.) it’s possible only drug dealers and firms paying their employees “under the table” will be using cash. Think about all the transactions you use debit or credit cards for each month. Like me, you might also be paying your bills electronically through your financial institution. And, as I mentioned earlier, only about 10% of M2 is actually currency; its circulation creates the rest of M2 in the worldwide banking system. Debit cards could easily replace this currency.

Hyperinflation In Zimbabwe

As I said before, the Quantity Theory of Money states that the growth rate in the money supply will equal the growth rate in the prices of goods and services in an economy (inflation rate) minus the growth rate in real Gross Domestic Product. Rearranging this equation, we have:

.png)

.png)

This is called the inflation equation. As we said above, although this relation does not hold for every year, it is accurate over the long run, a fact supported by the empirical evidence. To paraphrase the Nobel Prize winning economist, Milton Friedman, inflation is always and everywhere a money supply problem (1970).

As a thought experiment, imagine an economy with a certain (fixed) money supply. You need money to buy goods and services created within that economy (the GDP). Now let’s imagine that over time the money supply grows 10% greater (rate of growth = 10%) but the goods and services do not change at all (rate of growth= 0%). Therefore, the prices paid for the fixed amount of goods and services will be bid up by 10% (rate of inflation=10%).

For example, consider Robert Mugabe, the strongman dictator who ruled Zimbabwe for over 30 years. From 2007 to 2010, he created seismic shifts in his country’s monetary policy. Since he needed more money to run the government, to pay the military, and to buy imports, he simply ordered the Central Bank of Zimbabwe to print more money. Unfortunately, he printed so much money compared to the supply of goods and services that the rate of inflation in 2008 was over one billion percent (1,000,000,000%). As things became more expensive, the Central Bank had to print currency notes in larger and larger denominations so the residents would not have to carry money around in wheelbarrows to pay for food at the market.

In addition, Mugabe instituted poorly executed land reforms that did not help, but the root cause of the hyperinflation was printing too much money.

In 2009, so many people had lost confidence in the Zimbabwe dollar that the government had to allow the U.S. dollar and other foreign currencies to be used for payments. They also stopped printing the Zimbabwe dollar, which caused the inflation rate to drop precipitously. Even so, in 2010, it still cost 100 Billion Zimbabwe dollars to buy lunch. Eventually, the inflation rate in Zimbabwe was tamed (relatively, at least), and as of June 2019, the official inflation rate was 97.8% annually.