Summary

This chapter presented the aggregate expenditures model. Aggregate expenditures are the sum of planned levels of consumption, investment, government purchases, and net exports at a given price level. The aggregate expenditures model relates aggregate expenditures to the level of real GDP.

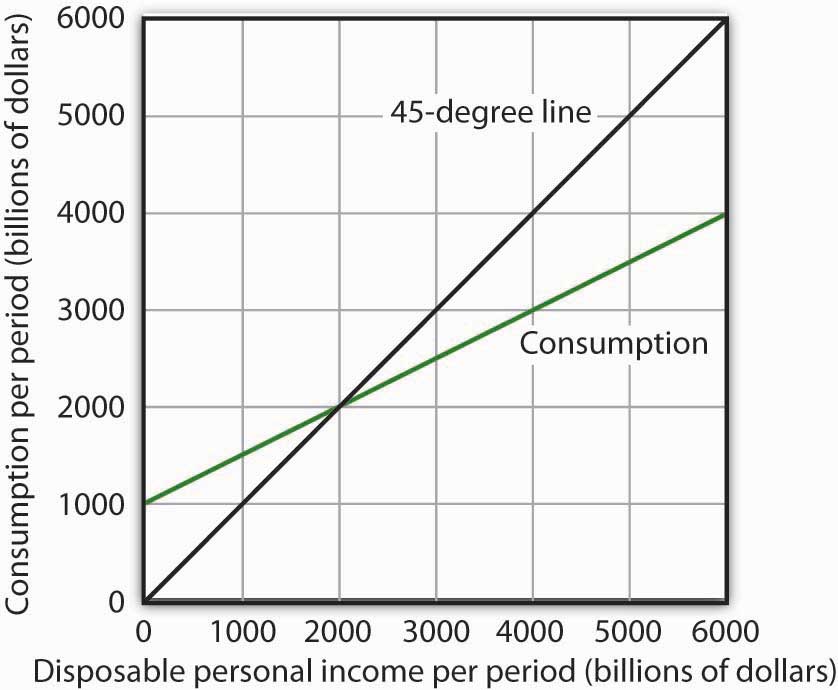

We began by observing the close relationship between consumption and disposable personal income. A consumption function shows this relationship. The saving function can be derived from the consumption function.

The time period over which income is considered to be a determinant of consumption is important. The current income hypothesis holds that consumption in one period is a function of income in that same period. The permanent income hypothesis holds that consumption in a period is a function of permanent income. An important implication of the permanent income hypothesis is that the marginal propensity to consume will be smaller for temporary than for permanent changes in disposable personal income.

Changes in real wealth and consumer expectations can affect the consumption function. Such changes shift the curve relating consumption to disposable personal income, the graphical representation of the consumption function; changes in disposable personal income do not shift the curve but cause movements along it.

An aggregate expenditures curve shows total planned expenditures at each level of real GDP. This curve is used in the aggregate expenditures model to determine the equilibrium real GDP (at a given price level). A change in autonomous aggregate expenditures produces a multiplier effect that leads to a larger change in equilibrium real GDP. In a simplified economy, with only consumption and investment expenditures, in which the slope of the aggregate expenditures curve is the marginal propensity to consume (MPC), the multiplier is equal to 1/(1 − MPC). Because the sum of the marginal propensity to consume and the marginal propensity to save (MPS) is 1, the multiplier in this simplified model is also equal to 1/MPS.

Finally, we derived the aggregate demand curve from the aggregate expenditures model. Each point on the aggregate demand curve corresponds to the equilibrium level of real GDP as derived in the aggregate expenditures model for each price level. The downward slope of the aggregate demand curve (and the shifting of the aggregate expenditures curve at each price level) reflects the wealth effect, the interest rate effect, and the international trade effect. A change in autonomous aggregate expenditures shifts the aggregate demand curve by an amount equal to the change in autonomous aggregate expenditures times the multiplier.

In a more realistic aggregate expenditures model that includes all four components of aggregate expenditures (consumption, investment, government purchases, and net exports), the slope of the aggregate expenditures curve shows the additional aggregate expenditures induced by increases in real GDP, and the size of the multiplier depends on the slope of the aggregate expenditures curve. The steeper the aggregate expenditures curve, the larger the multiplier; the flatter the aggregate expenditures curve, the smaller the multiplier.