10.6: Cartels- Acting like a monopolist

- Page ID

- 108414

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \) \( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)\(\newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\) \( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\) \( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \(\newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\) \( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\) \( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)\(\newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

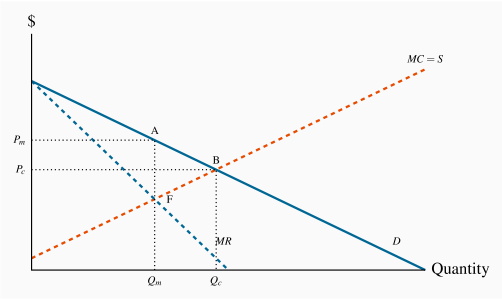

Figure 10.14 Cartelizing a competitive industry

A cartel is formed when individual suppliers come together and act like a monopolist in order to increase profit. If MC is the joint supply curve of the cartel, profits are maximized at the output Qm, where MC=MR. In contrast, if these firms operate competitively output increases to Qc.

Cartel instability

Application Box 10.1 The taxi cartel