1.1: Introduction- Sharing Pedagogical Authority- Practice Complicates Theory When Synergizing Classroom, Small-Group, and One-to-One Writing Instruction

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 74984

In short, we are not here to serve, supplement, back up, complement, reinforce, or otherwise be defined by any external curriculum. – Stephen North

Our field can no longer afford, if it ever could, to have forged a separate peace between classroom and nonclassroom teaching. There is no separate but equal. – Elizabeth H. Boquet and Neal Lerner

The intersecting contexts of on-location tutoring not only serve ... – Holly Bruland

Increasingly, the literature on writing centers and peer tutoring programs reports on what we’ve learned about teaching one-to-one and peer-to-peer from historical, theoretical, and empirical points of view. We’ve re-defined and re-interpreted just how far back the “desire for intimacy” in writing instruction really goes (Lerner “Teacher-Student,” The Idea). We’ve questioned what counts as credible and useful research methods and methodologies (Babcock and Thonus; Liggett, Jordan, and Price; Corbett “Using,” “Negotiating”) and meaningful assessment (Schendel and Macauley). We’ve explored what the implications of peer tutoring are, for not just tutees, but also for tutors themselves (Hughes, Gillespie, and Kail). And we’ve made connections to broader implications for the teaching and learning of writing (for example see Harris “Assignments,” and Soliday Everyday Genres on assignment design and implementation; Greenfield and Rowan, Corbett, Lewis, and Clifford, and Denny on race and identity; Mann, and Corbett “Disability” on learning-disabled students; Lerner The Idea and Corbett, LaFrance, and Decker on the connections between writing center theory and practice and peer-to-peer learning in the writing classroom). Since the first publication of North’s often-cited essay “The Idea of a Writing Center,” quoted above, writing center practitioners and scholars have continued to ask a pivotal question: How closely can or should writing centers, writing classrooms—and the people involved in either or both—collaborate (North “Revisting”; Smith; Hemmeter; Healy; Raines; Soliday “Shifting Roles”; Decker; Sherwood; Boquet and Lerner)?

Yet with all our good intentions, unresolved tensions and dichotomies pervade all our actions as teachers or tutors of writing. At the heart of everything we do reside choices. Foremost among these choices includes just how directive (or interventionist or controlling) versus how nondirective (or noninterventionist or facilitative) we wish to be in the learning of any given student or group of students at any given time. The intricate balancing act between giving a student a fish and teaching him or her how to fish can be a very slippery art to grasp. But it is one we need to think about carefully, and often. It affects how we design and enact writing assignments, how much cognitive scaffolding we build into every lesson plan, or how much we tell students what to do with their papers versus letting them do some of the crucial cognitive heavy-lifting. The nuances of this pedagogical balancing act are brought especially to light when students and teachers in writing classrooms and tutors from the writing center or other tutoring programs are brought together under what Neal Lerner characterizes as the “big cross-disciplinary tent” of peer-to-peer teaching and learning (qtd. in Fitzgerald 73). Like many teachers of writing, I started my career under this expansive tent learning to negotiate directive and nondirective instruction with students from across cultures and across the disciplines.

I started out as a tutor at Edmonds Community College (near Seattle, Washington) in 1997. When I made my way as a GTA teaching my own section of first-year composition at the University of Washington, in 2002, I took my writing-centered attitudes and methods right along with me. My initial problem was how to make the classroom more like the center I felt so strongly served students in more individualized and interpersonal ways. I began to ask the question: Can I make every writing classroom (as much as possible) a “writing center”? Luckily, I soon found out I was not alone in this quest for pedagogical synergy. Curriculum- and classroom-based tutoring offer exciting, dramatic instructional arenas from which to continue asking questions and provoking conversations involving closer classroom and writing center/tutoring connections (Spigelman and Grobman; Moss, Highberg, and Nicolas; Soven; Lutes; Zawacki; Hall and Hughes; Cairns and Anderson; Corbett “Bringing,” “Using,” “Negotiating”). In the Introduction to On Location: Theory and Practice in Classroom-Based Writing Tutoring Candace Spigelman and Laurie Grobman differentiate between the more familiar curriculum-based tutoring, usually associated with writing fellows programs, and classroom-based tutoring, where tutorial support is offered during class (often in developmental writing courses). But just as all writing centers are not alike, both curriculum- and classroom-based tutoring programs differ from institution to institution. There is much variation involved in curriculum- and classroom-based tutoring due to the context-specific needs and desires of students, tutors, instructors, and program administrators: Some programs ask tutors to comment on student papers; some programs make visits to tutors optional, while others make them mandatory; some have tutors attend class as often as possible, while others do not; and some programs offer various hybrid approaches. Due to the considerable overlap in theory and practice between curriculum- and classroom-based tutoring, I have opted for the term course-based tutoring (still CBT) when referring to pedagogical elements shared by both.

The following quotes, from three of the case-study participants this book reports on, begin to suggest the types of teaching and learning choices afforded by CBT, especially for developmental teachers and learners:

I feel like when I’m in the writing center just doing individual sign up appointments it’s much more transient. People come and you don’t see them and you don’t hear from them until they show up and they have their paper with them and it’s the first time you see them, the first time you see their work, and you go through and you help them and then they leave. And whether they come back or not it’s up to them but you’re not really as tied to them. And I felt more tied to the success of the students in this class. I really wanted them to do better.

– Sam, course-based tutor

One of the best features of my introductory English course was the built-in support system that was available to me. It was a small class, and my professor was able to give all of us individual assistance. In addition, the class had a peer tutor who was always available to help me. My tutor helped alleviate my anxiety over the understanding of assignments as she would go over the specifics with me before I started it ... When I did not understand something, my professor and tutor would patiently explain the material to me. My fears lessened as my confidence grew and I took more chances with my writing, which was a big step for me.

– Max, first-year developmental writer

I’d be interested in seeing how having a tutor in my class all the time would work, but at the same time one of the things I’m afraid of is that the tutor would know all the readings that we’re doing and would know the kinds of arguments I’m looking for and they might steer the students in that direction instead of giving that other point of view that I’m hoping they get from the tutor.

– Sarah, graduate writing instructor

We hear the voice of a course-based tutor at the University of Washington (UW), Sam, reflecting on her experiences working more closely with developmental writers in one course. We feel her heightened sense of commitment to these students, her desire to help them succeed in that particular course. We will hear much more about Sam’s experiences in Chapter Three. We also hear the voice of a developmental writer from Southern Connecticut State University (SCSU), Max, a student with autism who worked closely with a course-based tutor. Max intimates how his peer tutor acted much like an assistant or associate teacher for the course. He suggests how this tutor earned his trust and boosted his confidence, helping to provide a warm and supportive learning environment conducive to preparing him for the rigors of academic writing and communication. And, in the third quote, we hear from a graduate student and course instructor at the University of Washington, Sarah, who expresses her concern for having a tutor too “in the know” and how that more intimate knowledge of her expectations might affect the student writer/tutor interaction. We will hear much more from student teachers like Sarah (as well as more experienced classroom instructors) especially in Chapters Three and Four. Experiences like the ones hinted at by these three diverse students (at very different levels) deserve closer listening for what they have to teach us all, whether we feel more at home in the writing center or writing classroom.

Answering Exigencies from the Field(s)

While enough has been written on this topic to establish some theoretical and practical starting points for research, currently there are two major avenues that warrant generative investigation. First, although many CBT programs include one-to-one and group tutorials, there are few studies on the effects of participant interactions on these tutorials (Bruland; Corbett “Using”; and Mackiewicz and Thompson being notable exceptions). And only two (Corbett, “Using”; Mackiewicz and Thompson, Chapter 8) provide transcript reporting and analyses of the tutorials that frequently occur outside of the classroom. Valuable linguistic and rhetorical evidence that bring us closer to an understanding and appreciation of the dynamics of course-based tutoring—and peer-to-peer teaching and learning—can be gained from systematically analyzing what tutorial transcripts have to offer. Second, is the need for research on the effects of CBT with multicultural and nonmainstream students (see Spigelman and Grobman, 227-30). CBT provides the potential means for extending the type of dialogic, multiple-perspectival interaction in the developmental classroom scholars in collections like Academic Literacy in the English Classroom, Writing in Multicultural Settings, Bakhtinian Perspectives on Language, Literacy, and Learning, and Diversity in the Composition Classroom encourage—though not without practical and theoretical drama and complications.

Beyond Dichotomy begins to answer both these needs with multi-method qualitative case studies of CBT and one-to-one conferences in multiple sections of developmental first-year composition at two universities—a large, west coast R1 (the University of Washington, Seattle) and a medium, east coast master’s (Southern Connecticut State University, New Haven). These studies use a combination of rhetorical and discourse analyses and ethnographic and case-study methods to investigate both the scenes of teaching and learning in CBT, as well as the points of view and interpretations of all the participating actors in these scenes—instructors, peer tutors, students, and researcher/program administrator.

This book extends the research on CBT—and the important implications for peer-to-peer learning and one-to-one tutoring and conferencing—by examining the much-needed rhetorical and linguistic connections between what goes on in classroom interactions, planning, and one-to-one tutorials from multiple methodological and analytical angles and interpretive points of view. If we are to continue historicizing, theorizing, and building synergistic partnerships between writing classrooms and the peer tutoring programs that support them, we should have a deeper understanding of the wide array of choices—both methodological and interpersonal—that practitioners have, as well as more nuanced methods for analyzing the rhetorical and linguistic forces and features that can enable or deter closer instructional partnerships. This study ultimately presents pedagogical and methodological conclusions and implications usable for educators looking to build and sustain stronger pedagogical bridges between peer tutoring programs and writing classrooms: from classroom instructors and program administrators in Composition and Rhetoric, to writing center, writing fellows, supplemental instruction, and WAC/WID theorists and practitioners.

The lessons whispered by the participants in this book’s studies echo with pedagogical implications. For teaching one-to-one, what might Sam’s thoughts quoted above about being “more tied to the success of the students” or Sarah’s intimations regarding a tutor being more directly attached to her course add to conversations involving directive/nondirective instruction and teacher/tutor role negotiation? What might Max’s sentiments regarding writing anxiety—and how the pedagogical teamwork of his instructor and tutor in his developmental writing course helped him cope—contribute to our understanding of what pedagogical strategies tutors and teachers might deploy with struggling first-year students? In short, what are teachers, tutors, and student writers getting out of these experiences, and what effects do these interactions have on tutor and teacher instructional choices and identity formations? An important and related question for the arguments in this book, then, becomes how soon can developing/developmental student writers, potential writing tutors, and classroom instructors or teaching assistants be involved in the authoritative, socially, and personally complicated acts of collaborative peer-to-peer teaching and learning? When are they ready to model those coveted Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing “habits of mind essential for success in college writing?” When are they ready to balance between strategically directing thought and action and holding back when coaching peers to become more habitually curious, open, engaged, creative, persistent, responsible, flexible, and metacognitive? There are important pedagogical connections between how and with whom these habits of mind are fostered and how students develop as college writers (see, for example, Thaiss and Zawacki; Beaufort; Carroll) that studies in CBT can bring into high relief. In sum, this book will explore, elaborate on, and provide some answers to the following central question: How can what we know about peer tutoring one-to-one and in small groups—especially the implications of directive and nondirective tutoring strategies and methods brought to light in this book—inform our work with students in writing centers and other tutoring programs, as well as in writing classrooms? I’ll start this investigation by looking at why we should continue to build bridges that synergistically bring writing classrooms and tutoring programs closer together.

Reclaiming the Writing Classroom into “The Idea of a Writing Center”

Above we discussed the exigencies for this book’s case studies. But bridging and synergizing the best of writing center and writing classroom pedagogies could be considered the uber-exigency that gave birth to CBT programs in the first place. In his pivotal 1984 College English essay, Stephen North passionately let loose the frustrations many writing center practitioners felt about centers being seen as proofreading, or grammar fix-it shops, or as otherwise subservient to the writing classroom. In this polemical “declaration of independence,” North spelled out a, thereafter, much-repeated idea that writing tutors are concerned with producing better writers not necessarily better writing. North’s emphasis on writers’ processes over products, his insistence that the interpersonal talk that foregrounds and surrounds the one-to-one tutorial is what makes writing centers uniquely positioned to offer something lacking in typical classroom instruction (including the notion that tutors are not saddled with the responsibility of institutional judger-grader), touched on foundational writing center ideology. But North’s vehemence would also draw a theoretical and practical dividing line between “we” in the center and “them” in the classroom as well as a host of critiques and counterstatements (North “Revisting”; Smith; Hemmeter; Smulyan and Bolton; Healy; Raines; Soliday “Shifting”; Boquet and Lerner). Further, this divisive attitude may have also contributed to the self-imposed marginalization of the writing center in relation to the rest of the academy, as Jane Nelson and Margaret Garner—in their analyses of the University of Wyoming Writing Center’s history under John and Tilly Warnock—claim occurred in the 1970s and 1980s. The trend for arguing from a perspective of what we can’t or won’t do was stubbornly set.

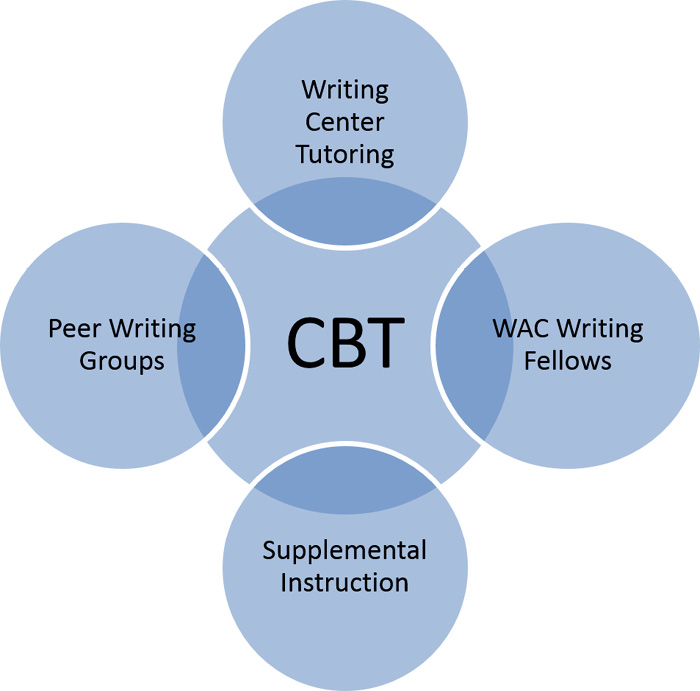

Though encouraging more of a two-way street between classroom and center, Dave Healy, Mary Soliday (“Shifting”), Teagan Decker, and Margot Soven have all drawn on Harvey Kail and John Trimbur’s 1987 essay “The Politics of Peer Tutoring” to remind us that the center is often that place just removed enough from the power structures of the classroom to enable students to engage in critical questioning of the “seemingly untouchable expectations, goals and motivations of the power structures” that undergraduates must learn within (Decker, “Diplomatic” 22). In another 1987 essay, Trimbur, drawing on Kenneth Bruffee’s notion of “little teachers,” warned practitioners of the problem of treating peer tutors as para- or pre-professionals and to recognize “that their community is not necessarily ours” (294). Bruffee and Trimbur worry that the collaborative effect of peership, or the positive effects of working closer perhaps to the student’s Vygotsykyan zone of proximal development, will be lost if tutors are trained to be too teacherly. Muriel Harris intimates, in her 2001 “Centering in on Professional Choices,” her own personal and professional reasons for why she prefers writing center tutoring and administration over classroom instruction. Commenting on her experience as an instructor teaching writing in the classroom, she opines: “Several semesters passed as I became ever more uneasy with grading disembodied, faceless papers, standing in front of large classes trying to engage everyone in meaningful group discussions, and realizing that I wasn’t making contact in truly useful ways with each student as a writer composing text” (431). She views her experiences in writing centers, in contrast, as enabling her to focus on “the copious differences and endless varieties among writers and ways to uncover those individualities and use that knowledge when interacting with each writer” (433). And there it is again, the scapegoat doing its potentially divisive work via one of the most influential voices in teaching one-to-one and peer-to-peer. Those of us theorizing, practicing, and advocating CBT, then, must stay wary of the sorts of power, authority, and methodological issues that might potentially undermine important pedagogical aspects of the traditional one-to-one tutorial. These same issues of authority—which touch importantly on concepts like trust-building and directive/nondirective tutoring—come into play as we look to the various “parent genres” that inform the theory and practice of the instructional hybrid that is CBT: writing center tutoring, WAC writing fellows programs, peer writing groups, and supplemental instruction (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The parentgenres that inform CBT.

The Protean State of the Field in Course-Based Writing Tutoring

As Spigelman and Grobman describe in their Introduction to On Location, the strength—and concurrent complexity—of CBT lies in large part to the variety of instructional support systems that can constitute its theory and practice, the way these instructional genres mix and begin to blur as they are called upon in different settings and by different participants to form the instructional hybrid that is CBT. The authors draw on Charles Bazerman and Anis Bawarshi to expand the notion of genre from purely a means of textual categorization to a metaphorical conceptualization of genre as location. In Bazerman’s terms genres are “environments for learning. They are locations within which meaning is constructed” (qtd. in Spigelman and Grobman 2). For Bawarshi, “genres do not just help us define and organize texts; they also help us define and organize kinds of situations and social actions, situations and actions that the genres, through their use, rhetorically make possible” (qtd. in Spigelman and Grobman 2). Rather than practice in the center, or in the classroom, rather than seeing teacher here and tutor there and student over there, CBT asks all participants in the dynamic drama of teaching and learning to realize as fully as possible the myriad possible means of connecting. For CBT, genre as location opens to the imagination visions of communicative roads interconnecting locations, communication roads that can be free-flowing or grindingly congested, locations where people inhabit spaces and make rhetorical and discursive moves in sometimes smooth, sometimes frictional ways. For Spigelman and Grobman, this leads to two significant features: a new generic form emerges from this generic blending, “but it also enacts the play of differences among those parent features” (4; emphasis added). This generic play of differences—between parent forms, between participants acting within and upon this ever-blurring, context-based instructional practice—makes CBT such a compelling location for continued rhetorical and pedagogical investigation.

Pragmatics begin to blend with possibilities as we begin to ask what might be. What can we learn from CBT theory and practice that can help us build more synergistic pedagogies in our programs, for our colleagues, with our students? Furthering Spigelman and Grobman’s idea of the play of differences, by critiquing the smaller instructional genres (themselves, already complex), readers will begin to gain an intimate sense of the choices involved in the design of protean, hybrid CBT programs and initiatives. This break-down of the parent instructional genres will also provide further background of the many ways practitioners have strived to forge connections between writing classrooms and writing support systems discussed above, and begin to suggest pedagogical complications like directive/nondirective instruction in the theory and practice of CBT.

Writing Center Tutoring

Writing center tutoring is the most obvious, influential parent genre to start with. Harris, Bruffee, and North have pointed to perhaps the key ingredients that make writing center tutorials an important part of a writing curriculum. Harris has helped many compositionists see that the professional choice of doing or supporting writing center work can add much to both students’ and teachers’ understanding of how writers think and learn. Harris claims, “When meeting with tutors, writers gain the kinds of knowledge about their writing and about themselves that are not possible in other institutional settings” (“Talking” 27). Bruffee similarly makes grand assertions for the role of peer tutoring in institutional change. Bruffee contends peer tutors have the ability, through conversation, to translate at the boundaries between the knowledge communities students belong to and the knowledge communities they aspire to join. Students will internalize this conversation of the community they want to join so they can call on it on their own. This mediating role, he believes, can bring about “changes in the prevailing understanding of the nature and authority of knowledge and the authority of teachers” (Collaborative Learning 110). But this theoretical idea of the ground-shaking institutional change that can be brought about by peer tutoring runs into some practical problems when we consider such dimensions as subject matter expertise, personality, attitude, and just how deeply entrenched the power and authority of the classroom instructor really is. A tutor snug, even smug and secure in his or her belief that they are challenging “the prevailing understanding” and authority of the teacher or institution in one-to-ones may be naively misconstruing the complex nature of what it means to teach a number of individuals, with a number of individual learning styles and competencies, in the writing classroom. Often the voices of hierarchical authority ring loud in tutors’ and students’ ears, understandably transcending all other motives during instructional and learning acts.

Tutors and instructors involved in CBT instructional situations bring their own internalized versions of the “conversations of the communities” they belong to or aspire to join. Some tutors, for example, bring what they have come to understand or believe as the role of a tutor—often imagined as a nondirective, non-authoritarian peer—into classroom situations where students may have internalized a different set of assumptions or beliefs of how instruction should function in order for them to join the sorts of communities they aspire to join. Instructors, in turn, may look to tutors to be more hands-on and directive or more minimalist and traditionally peer-like, often causing authority and role confusion between everyone involved. Bruffee compounds this dilemma of tutor authority with his view of the mediating role of peer tutors. In support of his antifoundational argument for education, in the second edition of Collaborative Learning, Bruffee distinguishes between two forms of peer tutoring programs: monitoring and collaborative. In the monitoring model, tutors “are select, superior students who for all intents and purposes serve as faculty surrogates under faculty supervision. Their peer status is so thoroughly compromised that they are educationally effective only in strictly traditional academic terms” (97). In contrast, Bruffee argues that collaborative tutors: “do not mediate directly between tutees and their teachers” (97); they do not explicitly instruct as teachers do, but rather “guide and support” tutees to help them “translate at the boundaries between the knowledge communities they already belong to and the knowledge communities they aspire to join” (98). Bruffee, however, does acknowledge the fact that no collaborative tutoring program is completely uncompromised by issues of trust and authority, just as no monitoring program consists only of “little teacher” clones.

As we will see in the following sections—and throughout this book—the issues raised by Harris and Bruffee become increasingly multifaceted as social actors play on their notions of what it means to tutor, teach, and learn writing in and outside of the classroom. In CBT situations, the task of assignment translation can take a different turn when tutors have insider knowledge of teacher expectations. The affective or motivational dimension, often so important in tutoring or in the classroom (especially in nonmainstream settings), can either be strengthened or diminished in CBT. And the question of tutor authority, whether more “tutorly” or “teacherly” approaches make for better one-to-one or small-group interactions, begins to branch into ever-winding streams of qualification.

WAC Writing Fellows

This idea of just how and to what degree peer tutoring might affect the power dynamics of the classroom leads us straight into considerations of writing fellows programs. The fact that writing fellows usually comment on student drafts of papers and then meet one-to-one with students, sometimes without even attending class or even doing the same readings as the students (as with Team Four detailed in this book), points immediately to issues of power, authority, and tutor-tutee-teacher trust-building relationships relevant for CBT. The role of the writing fellow also raises the closely related issue of directive/nondirective approaches to peer tutoring. These theoretical and practical challenges hold special relevance for writing fellows (Haring-Smith). While Margot Soven commented on such logistical issues as students committing necessary time, carelessly written student drafts, and issues of time and place in meetings in 1993, the issue most practitioners currently fret over falls along the lines of instructional identity, of pedagogical authority and directiveness. Who and what is a writing fellow supposed to be?

Several writing fellows practitioners report on compelling conflicts during the vagaries of authority and method negotiation (Lutes; Zawacki; Severino and Trachsel; Corroy; Babcock and Thonus 75-77; Corbett “Using,” “Negotiating”). Jean Marie Lutes examines a reflective essay written by a University of Wisconsin, Madison fellow in which the fellow, Jill, describes an instance of being accosted by another fellow for “helping an oppressive academy to stifle a student’s creative voice” (243). Jill defends her role as peer tutor just trying to pass on a repertoire of strategies and skills that would foster her peer’s creativity. Lutes goes on to argue that in their role as writing fellows, tutors are more concerned with living up to the role of “ideal tutor” than whether or not they have become complicit in an institutional system of rigid conventional indoctrination. In an instance of the controlling force of better knowing the professor’s goals in one-to-one interactions, another fellow, Helen, reports how she resorted to a more directive style of tutoring when she noticed students getting closer to the professor’s expectations. Helen concluded that this more intimate knowledge of the professor’s expectations, once she “knew the answer” (250 n.18) made her job harder rather than easier to negotiate. The sorts of give and take surrounding CBT negotiations, the intellectual and social pressures it exerts on tutors, leads Lutes to ultimately argue that “the [writing fellows] program complicates the peer relationship between fellows and students; when fellows comment on drafts, they inevitably write not only for their immediate audience (the student writers), but also for their future audience (the professor)” (239).

Clearly, as these cases report, the issue of changing classroom teaching practices and philosophies (to say nothing of institutional change) is difficult to qualify. It places tutors in a double-bind: The closer understanding of teacher expectations, as Bruffee warned, can cause tutors to feel obligated to share what they know, moving them further away from “peer” status. If they don’t, they may feel as if they are withholding valuable information from tutees, and the tutees may feel the same way, again moving tutors further away from peer status. Yet Mary Soliday illustrates ways this tension can be put to productive use. In Everyday Genres she describes the writing fellows program at the City College of New York in terms of how the collaborations she studied led professors to design and implement improved assignments in their courses. One of the keys to the success of the program, Soliday claims, involves the apprenticeship model, wherein new fellows are paired with veteran fellows for their first semester. Only after experiencing a substantial amount of time watching their mentors interact with professors—witnessing their mentors trying to grasp the purposes and motives of their professorial partners—were these WAC apprentices ready to face the complexities of negotiating pedagogical authority themselves (also see Robinson and Hall). Cautionary tales (like the ones presented in Chapter Three and Four of this book) have also led writing fellow practitioners to attempt to devise some rules of thumb for best practices. Emily Hall and Bradley Hughes, in “Preparing Faculty, Professionalizing Fellows,” report on the same sorts of conflict in authority and trust discussed above with Lutes. They go on to detail the why’s and how’s of training and preparing both faculty and fellows for closer instructional partnerships, including a quote intimated by a fellow that he or she was trained in “a non-directive conferencing style” (32).

But what, exactly, are the features of a “nondirective” conferencing style? Is it something that can be pinpointed and mapped? Is it something that can be learned and taught? And, importantly for this study, what useful connections might be drawn between directive/nondirective one-to-one tutoring and small-group peer response and other classroom-based activities?

Peer Writing Groups

And the pedagogical inter-issues don’t get any less complicated as we turn now to writing groups—what I view as the crucial intersection between writing center, peer tutoring, and classroom pedagogies central to CBT. Influenced by the work of Bruffee, Donald Murray, Peter Elbow, Linda Flower and John Hayes, Anne Ruggles Gere, and Ann Berthoff, in Small Groups in Writing Workshops Robert Brooke, Ruth Mirtz, and Rick Evans attempted to illustrate how students learn the rules of written language in similar ways to how growing children learn oral language—through intensive interaction with both oral and written conversations with their peers and teachers. Marie Nelson’s work, soon after to be deemed the “studio” approach in the work of Rhonda Grego and Nancy Thompson, provides case studies that supported Brooke, Mirtz, and Evans’s claims with compelling empirical evidence. For example, and especially pertinent to the case studies reported on in this book in Chapter Four, Nelson’s study of some 90 developmental and multicultural response groups identified consistent patterns of salutary development in students learning to write and instructors learning to teach. Student writers usually moved in an overwhelmingly predictable pattern from dependence on instructor authority, to interdependence on their fellow group members, ultimately to an internalized independence, confidence and trust in their own abilities (that they could then re-externalize for the benefit of their group mates). Nelson noted that this pattern was accompanied by, and substantially expedited when, the pedagogical attitudes and actions of the TA group facilitators started off more directive in their instruction and gradually relinquished instructional control (for a smaller, 2008, case study that supports Nelson’s findings see Launspach).

But as fast as scholars could publish their arguments urging the use of peer response groups, others began to question this somewhat pretty picture of collaboration. Donald Stewart, drawing on Isabel Briggs Myers, argued that people with different personality types will have more trouble collaborating well with each other. Brooke, Mirtz, and Evans, while ultimately arguing for the benefits of writing groups, also described potential drawbacks like students negotiating sensitive private/public writing issues with others, reconciling interdependent writing situations with other writing teachers and classes they’ve experienced that did not value peer-to-peer collaborative learning, or working with diverse peers or peers unlike themselves. In her 1992 “Collaboration Is Not Collaboration Is Not Collaboration” Harris, focusing on issues like experience and confidence, compares peer response groups and peer tutoring. She explains how tutoring offers the kind of individualized, nonjudgmental focus lacking in the classroom, while peer response is done in closer proximity to course guidelines and with practice in working with a variety of reviewers. She also raises some concerns. One problem involves how students might evaluate each other’s writing with a different set of standards than their teachers: “Students may likely be reinforcing each other’s abilities to write discourse for their peers, not for the academy—a sticky problem indeed, especially when teachers suggest that an appropriate audience for a particular paper might be the class itself” (379). Fifteen years later, Eric Paulson, Jonathan Alexander, and Sonya Armstrong report on a peer response study of fifteen first-year students. The researchers used eye-tracking software to study what students spend time on while reading and responding. The authors found that students spend much more time focused on later-order concerns (LOCs) like grammar and spelling than higher-order concerns (HOCs) like claim and organization, and were hesitant to provide detailed critique. While their study can be criticized due to the fact that the students in the study were responding to an outside text rather than a peer group member’s text, and none of the students had any training or experience in peer response, the findings echo Harris’s concerns regarding students’ abilities to provide useful response. Obviously, the issue here is student authority and confidence. If students have not been trained in the arts of peer response, how can they be expected to give adequate response when put into groups, especially if the student is a first-year or an otherwise inexperienced academic reader and writer? How can we help “our students experience and reap the benefits of both forms of collaboration?” Harris is curious to know (381).

Writing center and peer tutoring programs from Penn State at Berks, UW at Seattle, University of Connecticut at Storrs, and Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, among many others, have answered Wendy Bishop’s call from 1988 to be “willing to experiment” (124) with peer response group work. Tutors have been sent into classrooms to help move students toward meta-awareness of how to tutor each other. In effect, they become tutor trainers, coaching fellow students on strategies to employ while responding to a peer’s paper. But student anxiety around issues of plagiarism and autonomous originality are hard to dispel. Spigelman suggests that students need to know how the collaborative generation of ideas differs from plagiarism. If students can understand how and why authors appropriate ideas, they may be more willing to experiment with collaborative writing (“Ethics”). It follows, then, that tutors, who are adept at these collaborative writing negotiations, can direct fellow students toward understanding the difference. But as with all the issues we’ve been exploring so far, the issue of the appropriation of ideas is as Harris suggests a sticky one indeed. In another essay Spigelman, drawing on Nancy Grimm and Andrea Lunsford, comments on the desires of basic writers interacting with peer group leaders who look to the tutor as surrogate teacher (“Reconstructing”). She relates that no matter how hard the tutors tried to displace their roles as authority figures, the basic writers inevitably complained about not getting enough grammar instruction, or lack of explicit directions. While on the other hand, when a tutor tried to be more directive and teacherly, students resisted her efforts at control as well. Spigelman also relates how she experiences similar reactions from students. Her accounts, as with Lutes above, suggest that it is no easy task experimenting with and working toward restructuring authority in the writing classroom.

In the 2014 collection Peer Pressure, Peer Power: Theory and Practice in Peer Review and Response for the Writing Classroom (Corbett, LaFrance, and Decker) several essays attempt to provide answers to the authority and methods questions Harris and Spigelman raise. One of the recurring themes in the collection is the reevaluated role of the instructor in coaching peer review and response groups. Contributors like Kory Ching and Chris Gerben illustrate how instructors can take an active (directive) role in coaching students how to coach each other in small-group response sessions by actively modeling useful response strategies (also see Hoover). Ellen Carillo uses blogs and online discussions to encourage student conversation and collaborative critical thinking as an inventive, generative form of peer response. Carillo encourages students to question the nature of collaboration and to become more aware of the ways authors ethically participate in conversation as a form of inquiry. And Harris herself, in her afterword to the collection, offers in essence a revisit to her “Collaboration” essay. Like several other authors in the collection, Harris draws on writing center theory and practice, combined with classroom peer response practice, to speculate on how we just might be making some strides in working toward viable writing-center-inspired strategies for successful peer-to-peer reciprocal teaching and learning in writing classrooms. Ultimately, Harris’s summation of the collection, and her thoughtful extensions and suggestions, argue for a huge amount of preparation, practice, and follow-up when trying to make peer response groups work well, suggesting as E. Shelley Reid does, that perhaps peer review and response is the most promising collaborative practice we can deploy in the writing classroom. Harris realizes there are multiple ways of reaching this goal: “Whatever the path to getting students to recognize on their own that that they are going to have the opportunity to become more skilled writers, the goal—to help students see the value of peer review before they begin and then to actively engage in it—is the same” (281). Harris makes it clear that she believes a true team effort is involved in this process of getting students to collaboratively internalize (and externalize) the value of peer response, an effort that must actively involve student writers, instructors, and—as often as possible—peer tutors.

It is important that those practicing peer review and response come to understand just how useful the intellectual and social skills exercised and developed—through the reciprocity between reader/writer, tutor/student writer, tutor/instructor—really can be. Isabel Thompson et al. agree with Harris’s sentiments in their call for studies that compare and contrast the language of writing groups to the language of one-to-one tutorials. This line of inquiry would be especially useful for CBT, since tutors are often involved in working with student writers in peer response groups, usually in the classroom. I attempt exactly this sort of comparative analyses in Chapters Two, Three, and Four.

Supplemental Instruction

The final branch of peer education we will look at, supplemental instruction (SI), is given the least amount of coverage in peer education literature, though it purports to serve a quarter million students across the country each academic term (Arendale). SI draws theoretically from learning theory in cognitive and developmental educational psychology. There are four key participants in the SI program, the SI leader, the SI supervisor, the students, and the faculty instructor. The SI leader attends training before classes start, attends the targeted classes, takes notes, does homework, and reads all assigned materials. Leaders conduct at least three to five SI sessions each week, choose and employ appropriate session strategies, support faculty, meet with their SI supervisor regularly, and assist their SI supervisor in training other SI leaders (Hurley, Jacobs, and Gilbert). SI leaders work to help students break down complex information into smaller parts; they try to help students see the cause/effect relationship between study habits and strategies and resulting performances; and because they are often in the same class each day, and doing the same work as the student, they need to be good performance models. SI leaders try to help students use prior knowledge to help learn new knowledge, and encourage cognitive conflict by pointing out problems in their understandings of information (Hurley, Jacobs, and Gilbert; Ender and Newton). In this sense, supplemental instruction also demands that SI leaders, much like tutors, must negotiate when to be more directive or nondirective in their pedagogical support.

Spigelman and Grobman report on the links between supplemental instruction and composition courses. Drawing on the work of Gary Hafer, they write: “Hafer argues that it is a common misperception that one-to-one tutoring works better than SI in composition courses, which are not identified as high-risk courses and which are thought by those outside the discipline to be void of ‘content’” (236). In Hafer’s view, the goals of SI have more in common with collaborative composition pedagogy than do one-to-one tutorials in the writing center. These choices between what one-to-ones are offering versus what other potential benefits may present themselves with other peer tutoring models make for interesting comparative considerations and potential instructional choices. Several of the case studies I’ve been involved in over the years, including ones reported on in this book, incorporate several prominent features of the SI model, including tutors attending class on a daily basis, doing the course readings, and meeting with student writers outside of class. (For more on SI, visit the website for the International Center for SI housed at the University of Missouri at Kansas City.)

The rest of this book sets up and presents case studies of my experimentation over the years with hybridizing these parent genres that make up CBT. I illustrate the many ups and downs of diverse people with different personalities and views of “best practices” in teaching and learning to write trying to get along, trying to understand how they might best contribute to a synergistic instructional partnership while attempting to realize the best ways to impart the most useful knowledge to developing student writers. Synergy (from the ancient Greek synergia or syn- “together” and ergon “work”) involves identifying the best of what each contributing collaborator has to offer. As we’ve been touching on, one of the most crucial considerations tutors—indeed any teacher—must face in any instructional situation is the issue of how directive versus how nondirective they can, should or choose to be and, importantly, how this intertwines with the issue of authority and trust negotiation. Kenneth Burke writes, “we might well keep in mind that a speaker persuades an audience by the use of stylistic identifications ... So, there is no chance of our keeping apart the meanings of persuasion, identification (‘consubstantiality’) and communication (the nature of rhetoric as ‘addressed’)” (Rhetoric 46). This book aims to focus our attention on the importance of these interpersonal “stylistic identifications,” urging teachers and tutors to consider the true balancing act demanded by the directive/nondirective pedagogical continuum.

Chapter Summaries

Chapter One, takes a careful look at the ongoing rhetoric of directive and nondirective tutoring strategies. This issue has a long history in writing center literature, and it brings us to the heart of some of one-to-one teachers’ most closely-held beliefs and practices. I examine the conflict inherent when tutors are brought into the tighter instructional orbit that is CBT and how practitioners have dealt with thorny issues of instructional authority and role negotiation when moving between center and classroom. Carefully analyzing the literature on peer tutoring, I argue that CBT contexts demand a close reconsideration of our typically nondirective, hands-off approach to tutoring, that tutors involved in CBT, especially with developmental students, can better serve (and be better served) if they are encouraged to broaden their instructional repertoires, if directors and coordinators cultivate a more flexible notion of what it means to tutor in the writing center, in the classroom, and in between. I begin exploring, however, the complications involved in this idealistic notion of instructional flexibility.

Chapter Two offers the multi-method, RAD-research case study methods and methodology employed in Chapters Three and Four. I begin to offer some of the back-story on the dramatic effects the widely varying level of interaction in and out of the classroom—as well as variables like tutor experience, training, identity, and personality—ended up having on participants’ actions in and perceptions of their CBT experiences. I detail methods of analyses for one-to-one tutorials for Chapter Three and peer response groups in Chapter Four.

Chapter Three presents and analyzes the one-to-one tutorials that occurred with four teams from the UW. Audio-recorded one-to-one transcripts are the central focus of analysis used to explore the question: What rhetorical and linguistic patterns surface during one-to-one tutorials, and what relationship (if any) do participant interactions and various CBT contexts have on these one-to-ones? I carefully analyze how the discourse features of tutorial transcripts such as number of words spoken, references to instructors and assignment prompts, overlaps, discourse markers, pauses and silences, and qualifiers hint at larger rhetorical issues involved in the drama of closer collaboration. I attempt to triangulate and enrich these linguistic analyses comparatively with the points of view of participants.

Chapter Four provides the findings and analysis of CBT partnerships from the UW and SCSU engaged in small-group peer review and response facilitation and other classroom interactions. While field notes from in-class observations offer my views, I also present interviews and journal excerpts from the participants and report on feedback from students to provide more perspectives on these interactions. This chapter points to some illuminating findings that, when compared to the studies of one-to-one tutorials from the UW, offer readers an intimate look at the myriad choices practitioners have with CBT—and the teaching and learning implications involved for all participants.

In the Conclusion I discuss implications of this study’s findings in relation to my primary research question: How can what we know about peer tutoring one-to-one and in small groups—especially the implications of directive and nondirective tutoring strategies and methods—inform our work with students in writing centers and other tutoring programs, as well as classrooms? I begin with the implications of how this question played out in all aspects of the case studies, from the participants’ points of view, to the one-to-one tutorial transcript analyses and interpretations, and finally to the peer response sessions and other classroom activities I observed and followed up on. Finally, I open the conclusion to implications for tutor education and development, program building, and I suggest choices for teaching, learning and researching writing including interconnections between one-to-one and small-group teaching and learning.