2: Hybrid and Fully Online OWI

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 77971

- Beth L. Hewett and Kevin Eric DePew, Editors

- WAC Clearinghouse

Chapter 2. Hybrid and Fully Online OWI

College of DuPage

This chapter outlines key similarities and differences between hybrid and fully online writing instruction. Both instructional settings offer challenges and opportunities and neither is necessarily preferable to the other in all circumstances. Nor should these instructional settings be understood as mere variants of the imagined norm of fully face-to-face instruction. In fact, creating and delivering effective writing classes requires grounding in basic principles of sound pedagogy regardless of instructional setting.

Keywords: accessibility, blended, fully online, hybrid, institutional planning, instructional design, instructional setting, marketing, professional development, scheduling, student engagement, student success, student support

Early in my teaching career, I had a situation that highlighted some of the perils of teaching a hybrid FYW course. It was final exam week, and I was headed to the classroom where my hybrid composition class was scheduled to take its final exam, an in-class reflective essay. Lo and behold, the room was already occupied by another class taking its final exam. My students were waiting nervously in the hallway. I started to get nervous, too. I double-checked the exam schedule and, yes, this was where we were supposed to be. We were a Tuesday/Thursday class and this room was where we were to meet for our final exam and this was the right time... . Now what? Luckily, there was an available room not too far away, so my students and I moved there and they wrote their essays.

Later, I tried to figure out the mix up. Were two classes accidentally scheduled into the same room at the same time during finals week? I reread the final exam schedule and this time saw when our final was supposed to have occurred. I realized that the error was mine and that it was a revealing one.

I had mistakenly assumed that my FYW class, a hybrid that met face-to-face on Tuesday but not on Thursday, would still be treated as a “Tuesday/Thursday” class for final exam scheduling purposes. Despite everything I thought I knew about effective hybrid course design, I still basically understood my class as a Tuesday/Thursday class that just did not meet face-to-face on Thursdays throughout the term. For some reason, I seemed to have thought of my course as just a variation, maybe even a deficit model, of face-to-face instruction since it “skipped” a part of its physical meeting time every week. The result was that I instructed the class to meet in the wrong room for the exam.

It is hard to pinpoint exactly where or how this notion arose for me. As for many writing teachers, it may have emerged from a lack of institutional support for hybrid learning, at least in its earliest existence at my campus, in the form of professional development opportunities and cross- or inter-disciplinary conversations. Interestingly, in order to teach a hybrid course at my institution, faculty must complete an administrative form. The first question asks for a descriptive paragraph indicating “the differences between the traditional format offering of this course and the proposed hybrid format” (“Request to Teach Hybrid Delivery Course”). Why did this form not ask simply for a descriptive paragraph about the “proposed hybrid format”? Why was the hybrid positioned immediately as a variant?

While the language on the form may not be ideal, some sort of administrative process for distinguishing the hybrid course certainly was important because it ideally ensured that the course would be identified as hybrid in the registration system, enabling students to know (and choose) the course setting in advance. Additionally, faculty certainly had to think about course design at some point, and doing so at the outset has its advantages. My point, however, is that the hybrid proposal form positioned the hybrid setting only relative to the traditional, onsite course setting, inviting faculty to think about the hybrid OWC as relational alone. In considering my mistake with the hybrid course’s final exam, I simply may have lost sight of the fact that my hybrid OWC could be—even needed to be—understood as in a unique setting and not just relative to an established or implicitly normative instructional setting.

As I have studied hybrid learning and now become its spokesperson for the CCCC OWI Committee (Snart, 2010), I realized that a hybrid is its own unique kind of course. It is not face-to-face learning with a piece missing—not a deficit model. Nor is it a “class and a half,” with all the instructional material I normally would present face-to-face, somehow compressed into half the time, in addition to an online component.1 Similarly, a fully online OWC is not just a digital mirror of the traditional onsite course. Both the hybrid and fully online OWCs are as unique to their electronically mediated environments as they are similar to what many experienced teachers still consider the norm of a brick-and-mortar classroom.

This chapter addresses hybrid (sometimes called blended) and fully online educational environments as course settings both in terms of what they share in common and how they differ. Foundational Practices of Online Writing Instruction is explicitly about teaching writing in the online setting, which of course is where the hybrid and fully online settings implicitly are most alike. The hybrid OWC, however, is a balance of onsite and online environment and pedagogical strategies in nuanced ways. This chapter therefore gives hybrid OWCs more explicit consideration as a primary way of addressing the similarities and differences. In particular, I emphasize access, seat time, course organization, and course design, especially in terms of engaging students and allowing for both students and instructors to become invested and to see learning, fully online or otherwise, as at least to some degree a personality driven endeavor rather than an isolated, mechanical set of tasks to be completed.

Hybrid and Fully-Online OWCs

For the purposes of this book, the term hybrid describes an environment where traditional, face-to-face instruction is combined with either distance-based or onsite computer-mediated settings. Sometimes, hybrid courses are conducted through computer-mediation while face-to-face in an onsite computer lab (Hewett, 2013, p. 197; see also Chapter 1). This definition of hybrid course settings allows for the wide variety of ways in which instructional settings can be combined in the hybrid format. A fully online course setting describes classes with no onsite, face-to-face components. It occurs completely “online and at-a-distance through an Internet or an intranet”; students can connect to the course from short distances such as the campus or longer geographic distances such as across national or international borders (p. 196). When inclusivity and equitable access are factored into the equation, fully online instruction may make use of—while not requiring—alternative communicative venues such as the phone or onsite conferences (when geographically possible and amenable to both student and teacher).

I often hear from colleagues that institutions considering moving their curricula online will envision a face-to-face course that might become a hybrid class that might then become a fully online class. Although each of these courses will share something in common given that they ostensibly cover the same material, to imagine instructional settings as mere variations of one another is unlikely to produce either good hybrid or good fully online OWCs. Scott Warnock (2009) noted that some teachers may be able to “view [their] move into the online teaching environment as a progression that will begin with teaching a hybrid first” (p. 12). Yet, even though hybrid instruction may appear to be a middle ground or even a step between tradition and fully online instruction, such a perspective misses the nuances and challenges of hybrid learning for OWI as well as the need to design both hybrid and fully online OWCs with the instructional setting in mind from the ground up.

Finally, because hybrid and fully online OWI already occur in higher education, their potentially effective practices need to be addressed. In other words, this chapter will not debate the merits of hybrid and fully online OWI in terms of whether they should or should not exist at all. To be sure, this debate is hardly settled; a 2013 Inside Higher Ed survey of faculty attitudes toward online learning indicated that fewer than half of those surveyed believe that online courses are as effective as face-to-face courses (Lederman & Jaschik, 2013). Nonetheless, to debate the value of instructional settings that already are a mainstay at many institutions does not seem productive, as the CCCC OWI Committee observed in The State of the Art of OWI (CCCC OWI Committee, 2011c, p. 2).

Similarities between Hybrid and Fully Online OWCs

Hybrid and fully online OWCs are similar in that they both involve instructional time mediated by technology. Even though a hybrid OWC meets at least part of the time in a traditional face-to-face setting, it uses the electronic environment for similar activities and teaching purposes. In both settings, the computer or other devices are used for such activities as:

- Word processing

- Paper submission and reposting to the student

- Peer review activities

- Discussion forums

- Journal and other writing

- One-to-one and one-to-group/class communications such as instant messages, email, and message board2 postings

- Wiki/collaborative writing development

Chapter 4 particularly enumerates some of these activities as pedagogical strategies for writing instruction.

In the fully online setting, which remains new to many students and teachers, activities typically occur asynchronously, making time one of the key distinctions of fully online OWCs from both hybrid and traditional learning (see Chapter 3 for a discussion of asychronicity and synchronicity). Both teachers and students need to learn to use the technology for activities that they previously have experienced as synchronous, oral, and aural. Thus, writing becomes a way of speaking and reading a way of listening (Hewett, 2010, 2015a, 2015b), which means that the literacy load increases exponentially (Griffin & Minter, 2013; Hewett, 2015a) leading potentially to stronger writing skills through sheer amount of text as well as focused communicative effort and, of course, attempting to meet course goals (Barker & Kemp, 1990; Palmquist, 1993). In a hybrid setting, on the other hand, some unique concerns arise—consequently, my focus on the differences among hybrid, fully online, and face-to-face learning in this chapter. Many of the issues that arise for hybrid learning are pertinent to fully online OWCs, but hybrid OWI also involves a balance with traditional writing instruction that fully online instruction does not.

Differences between Hybrid and Fully Online OWCs

The primary difference between hybrid and fully online OWCs, at least in their most basic forms, is the degree of physical face-time, or seat time, involved (see Table 2.1).

Table 2.1. Primary differences between hybrid and fully online OWCs

|

Hybrid Writing Course |

Fully Online Writing Course |

|

Some face-to-face classroom interaction |

No face-to-face classroom interaction |

|

Some distance-based online learning as determined by institutional needs |

Completely distance-based online learning |

This distinction of face-time may seem elementary, but it is essential. Educators need to understand hybrid and fully online course settings as unique because, from a design perspective, no instructional setting should be understood as so much a version or variation of another that the job of the instructional designer or teacher is simply to migrate learning materials from one setting to the other. Indeed, given the potential dilemma of trying to see instructional settings as both deeply related but necessarily unique, two key OWI principles should be coordinated. OWI Principle 3 stated that “appropriate composition teaching/learning strategies should be developed for the unique features of the online instructional environment” (CCCC OWI Committee, 2013, p. 12). OWI Principle 4, on the other hand—and seemingly contradictorily—indicated that “appropriate onsite composition theories, pedagogies, and strategies should be migrated and adapted to the online instructional environment” (p. 14). As Chapter 1 revealed, there remains a need to develop strategies and theories unique to the online setting while using the most appropriate of current strategies developed from traditional, onsite learning.

Migration is a pedagogical approach that OWI Principle 4 acknowledges and that Warnock (2009) advocated, yet migration alone may lead to poorly designed courses and low teacher and student satisfaction. The notion of adaptation is crucial to understanding the practicality behind OWI Principle 4. Even where basic pedagogies can be applied across instructional settings, they invariably will need to be adapted to suit the new context. Migration of strategies and theories to either online setting necessitates adaptation because it ultimately requires that the learning strategy or pedagogy be reimagined relative to what is happening in a course as a whole. Although it may seem counterintuitive, such is especially true for hybrid instruction, where onsite composition strategies are transferred from the fully face-to-face instructional setting to one that includes an onsite, face-to-face component but has an equally important online component. In other words, just because a teaching strategy from an onsite, face-to-face class is migrated into the face-to-face portion of a hybrid class does not mean that that strategy will function equivalently in both settings. That teaching strategy will bear a new relationship to what is going on around it.

For example, I have often used a peer group technique in my fully onsite composition classes in which students work in teams of three or four to develop a set of relevant questions about a text we are reading. Although I transferred this technique into my hybrid writing class, it exists differently in that setting. In the fully onsite context, the questions that the students develop are then posed orally, in real-time, to other student teams in the class. Oral discussion continues as we narrow our set of questions to one or two key approaches for writing about what we have read. In the hybrid setting, students take their group questions from the oral portion of the class and then post them to their online discussion board. All students then evaluate and respond to each group’s questions using writing. It is not until a later face-to-face class period that we return orally to the initial questions that students developed in class and the response material that has been generated online. Thus, the initial group activity exists in both the face-to-face and hybrid iterations of the writing class, but it exists differently because of how it interacts with other environmental elements in the course. Transferring the same activity to a fully online course typically means that no oral discussion occurs, making all discussion about the readings text-based, with the activity occurring perhaps in two separate discussion forums. Students become responsible for listening to their classmates through reading their remarks and then for talking through written responses; the process can lead to thoughtful discussions if well handled (Warnock, 2009), but the give-and-take of the discussions differs considerably from that of the oral ones (Hewett, 2004-2005). That said, because an LMS might offer synchronous conferencing, it is possible (yet likely uncommon) to return some of the traditional oral discussion to the process.

One practical difference regarding how this activity functions concerns the quality of the developed questions. Because students in the hybrid writing course ultimately post their questions in text to a discussion board, those questions tend to be more refined and focused relative to what is generated and then shared immediately in their real-time, face-to-face setting—the setting that they have in common with onsite courses. The quality of these initial questions has implications for how students’ writing process unfolds, since those in the hybrid setting tend to start writing with questions that already are somewhat refined and focused, as they might be in the fully online setting as well. In the fully onsite setting, to achieve a similar quality of initial questions, one must build writing time into the class meetings such that students can work textually, rather than just orally, to refine the questions generated in the initial inquiry period.

With this sense of migration as necessitating adaptation, educators can see both the hybrid and fully online OWI settings as unique from the traditional onsite one rather than as distortions of other instructional settings, transitional steps from one setting to another, or somehow as lesser relatives of an imagined norm. But even as unique instructional settings, both hybrid and fully online OWI share the same need for grounding in solid pedagogy and effective practice, and in both cases educators will need to provide opportunities for student engagement and success.

Therefore, while certain onsite, face-to-face teaching and learning strategies naturally will find their way into hybrid and fully online OWCs, OWI Principle 3 requires consideration (p. 12) as described in Chapter 1. New strategies may require new theory to explain why and how they can work effectively in online settings. Such strategies may include teaching students using a combination of text and audio/video media and providing text in visually appealing (hence, more readable) ways.

Ultimately, some obvious differences between these two technologically enhanced teaching settings notwithstanding, they share the need to be grounded in effective pedagogical practices, as described in the OWI principles. Furthermore, regardless of instructional setting, faculty need to be supported by their institutions when working in either course setting. What makes for a successful learning experience is not the technology or any particular personality type working within a given setting, but rather accessible tools to engage students’ creativity and ingenuity and to help them realize an intellectual and emotional presence in the learning environment, digital or otherwise.

Nuances that Define Instructional Setting

Institutional Definitions

There can be many variables at work in defining the parameters of hybrid and fully online OWCs, such that the relatively straightforward comparison presented in Table 2.1 quickly becomes more nuanced with each variation presenting new implications for design and teaching. For example, in some cases, institutions might require limited onsite meeting times in what they call fully online instruction to meet institutional desires or perceived needs. Students might be required to take major tests or complete timed writing assignments in a proctored environment, be it a campus testing center or other designated testing site, for example. This scenario begs the question of exactly what is a fully online setting, while it illustrates how policies designed for all online instruction may not be universally applied and in some cases may be detrimental to the ways that courses in certain disciplinary material, like OWI, can be taught.

Many institutions have developed course classification guidelines such that a course that is entirely distance-based is defined as fully online (although as indicated earlier, in certain cases this setting might still require physical trips to campus, belying its classification as fully online). In the case of hybrid OWCs, there always will be both a physical classroom component and an online component, but the exact ways in which these two instructional settings are combined is dependent on individual instructor choices and on institutional requirements that mandate a minimum or maximum time for one instructional setting relative to the other. A course that is predominantly face-to-face, but trades some limited seat time for online work may be called Web-enhanced (or another equivalent term), yet its needs are similar to the hybrid course.

There being no single definition, the hybrid OWC appears to be the most nuanced in terms of how it is defined and structured within various institutions. One institution’s hybrid course description read, “You will periodically meet on campus for face-to-face course sessions with your instructors” (Kirtland Community College, 2014). For another institution, the hybrid OWC was defined a little more specifically: “at least 30% of the course content is delivered through the Internet” (Ozarks Technical Community College, 2014). The “Hybrid Courses” website for the College of DuPage (2013) indicated that “hybrid courses integrate 50 percent classroom instruction with 50 percent online learning.” Unfortunately, even this description is not exact, as anybody who teaches a Monday/Wednesday/Friday class in the hybrid format will realize, since that type of class is unlikely to split classroom and online time fifty-fifty each week. The Sloan Consortium defined a “blended” course—another term for the hybrid course—as one for which the online component comprises from 30% to 79% of a course (Allen, Seaman, & Garrett, 2010). Each of these definitions leads to a somewhat different course setting where the oral and written features of the course play out differently and uniquely.

With increasingly accessible and usable technological affordances available to higher education, there has grown a new diversity of instructional settings that can be bundled within one course. There are fully online classes during which students experience no physical face-to-face time with peers or their instructors. Sometimes, though, fully online classes can involve a portion of class time that is conducted online synchronously, so there is face-time but instead of being physical, it is virtual. Such a synchronous online meeting requires that everyone be able to attend the course at the same time and day of the week; it must be so listed in the registration guide. Alternately, classes might be conducted entirely face-to-face onsite while also meeting in a computer lab such that while all class participants are physically together, in real-time, the class work occurs largely at the computer: students write, research, or collaborate digitally, all while synchronously, physically present. Still other classes might involve a mix of face-to-face time in a classroom with computer lab time. And, in so-called traditional classrooms, students may be asked to work with and present to peers using the enhanced technology of networked, digital tools. Finally, as Chapter 16 explains, mobile learning, which involves the use of handheld networked devices like smartphones, is becoming a feasible reality in some instructional settings, which means that teachers need to be aware of the kinds of hardware on which students might be learning.3 It is hard to imagine what else might be on the horizon when it comes to technology and teaching.

Realistically, higher education institutions probably will not come to agreement on precise definitions for various course settings. On a practical level, overly standardized course setting definitions might cause institutions to lose the ability to adapt course settings to their own unique needs. However, defining course type clearly matters on several levels. Students who take classes at various institutions would benefit from knowing whether a hybrid class at one campus is roughly the same as a hybrid at another campus from which they might select a course. Additionally, broadly standardized definitions may help policy-making organizations across higher education speak to each other and to their member constituents in consistent ways. Ideally, some level of standardization will happen at the institutional level as individual campuses develop and refine their unique approaches to instructional design and delivery. Such standardization would enable local faculty, who have direct contact with a particular body of students, to have a voice at the table.

Perhaps most important regarding course setting definitions, students should be provided with as much information as possible about what a hybrid or fully online writing class might entail before registering, which means that academic advisors and counselors need to be fully versed in what these course types involve. Student preparedness for any online setting is, according to OWI Principle 10, an institutional responsibility primarily (p. 21). To this end, students should be informed about course setting and its requirements as part of the registration process. Many registration systems provide students with boiler plate language describing a hybrid course as involving some face-time and some online time but offer no further specifics. Therefore, a student might register for three separate hybrid courses, each of which coordinates onsite and online instruction differently, and each of which requires adjustments in the student’s schedule and work habits. Setting student expectations accurately and appropriately is one way to help them avoid potentially unnecessary attrition or failure.

Access Issues

Access concerns also play out in OWI with respect to how an OWC is defined institutionally, making OWI Principle 1, which calls for inclusivity and accessibility (p. 7), relevant to course description. Take the aforementioned fully online course that requires any kind of onsite meetings. In the strictest sense of the OWI environment, requiring onsite meetings means that the learning no longer is fully online, and using this terminology not only may confuse students and teachers but likely will limit access to some. For example, generally it would be impossible for a geographically distributed student in Colorado to attend a meeting at a Virginia institution in which she is enrolled as an online student. An accessible OWC would not ask such travel of its students. However, Texas is one state with state-mandated definitions for instructional settings, and it defined a “fully distance education course” as, “A course which may have mandatory face-to-face sessions totaling no more than 15 percent of the instructional time. Examples of face-to-face sessions include orientation, laboratory, exam review, or an in-person test” (Texas Administrative Code, 2010, RULE §4.257). Anecdotally, I have seen another interesting case occurring in Speech Communications. Since the majority of a student’s grade is based on speeches delivered to the class, some programs have instituted a requirement that students taking a fully online class must be prepared to come to campus periodically throughout the term in order to speak in real-time in front of a live audience; it is easy to imagine similar scenarios with Technical Communication, multimodal writing, and even some FYW courses. Having online students record themselves speaking and then supplying that file to an instructor presents a number of difficulties, not least being how to manage large video files. In any case, when fully online classes are defined in this manner, they are neither one-hundred percent online nor fully accessible, which detracts significantly from the nature and benefits of a fully online course.

Transparent advertising of the kind described above also is a basic access issue. If students know that a particular course setting will require a certain amount of virtual and physical time in a classroom relative to time online courses, they can discern, self-disclose, and indicate necessary accommodations. Furthermore, with a good understanding of the learning settings available to them, students can make informed decisions about which instructional setting best suits their needs and abilities. Their decisions can help them to self-place into appropriate course sections that take advantage of useful onsite and online affordances. Without institutionally standardized language that defines various course settings, advertising to students becomes difficult and many will find themselves in classes that are not suited to their needs or abilities. I am frankly and consistently surprised to discover how many students arrive to my hybrid writing classes not knowing that the class is a hybrid and/or not knowing what that term means generally or for their writing work specifically.

In other cases, despite what the CCCC OWI Committee’s effective practices research indicates, some institutions may not have fully developed student resources that are available online, including writing center/tutor (OWL), library, or IT support. So students might enroll in a fully online OWC, but if they need additional instructional or research support, or if they have basic IT issues, a trip to campus might be required. Such a campus visit can be impossible for some students; a lack of online support limits reasonable access to such resources as suggested by OWI Principle 13 (p. 26). Note that OWI Principle 13 emphasized digital access as primary for online learners as opposed to being merely an adjunct to it. How “online” is an online course for which most of the student support is only available onsite at a campus setting?

Table 2.2. Instructional settings, modality, and components

|

Instructional Setting |

Synchronous |

Asynchronous |

Online |

Face-to-face Component |

|

Onsite |

Yes |

Maybe |

Maybe |

Yes |

|

Fully Online |

Maybe |

Yes |

Yes |

Maybe |

|

Hybrid |

Yes |

Maybe |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Web-enhanced |

Yes |

Maybe |

Yes |

Yes |

Table 2.2 illustrates the types of learning that might happen through digital tools in different instructional settings. These varied tools have ramifications for the socioeconomically challenged, for example. Given how education, and particularly writing instruction, has become increasingly technologized, the degree to which students have equal technology access also is diversified. A Position Statement of Principles and Example Effective Practices for OWI indicated that “learning challenges related to socioeconomic issues (i.e., often called the digital divide where access is the primary issue) must be addressed in an OWI environment to the maximum degree” (p. 7). To this end, while I note differences and similarities between hybrid and fully online OWI throughout this chapter, all students should have equitable access to learning resources regardless of instructional setting; therefore, students’ learning needs, preferences, and general access should inform decisions between hybrid and fully online course settings.

Furthermore, educators always must ask the costs of such necessary resources. Literally, what is their cost? The New Media Consortium’s Horizon Report (2013) noted, for example, that “Tablets have gained traction in education because users can seamlessly load sets of apps and content of their choosing, making the tablet itself a portable personalized learning environment” (p. 15). Who buys the tablet? Who pays for the apps? Who provides the broadband Internet connection? And who buys the new tablet three years later when the old one is out of date? Indeed, while the digital divide might be shrinking, it has not disappeared. A recent Pew Research Center report (Zickhur, 2012) indicated that “While increased Internet adoption and the rise of mobile connectivity have reduced many gaps in technology access over the past decade, for some groups digital disparities still remain” (p. 1). Therefore, when thinking about questions of technology and the role it plays in effective hybrid and fully online writing instruction, we should not lose sight of educational equity and access to resources. This one aspect of instructional design and delivery perhaps unites all instructional settings.

Instructional Place and Time

Consider also the effect that digital student support availability has on instructional design. For example, if there is little-to-no research support offered online, to what degree can certain kinds of research or digital literacy projects be included in a fully online OWC? Or, when those types of assignments are included (since they are fundamental to many writing courses), how might lack of fully online support services negatively affect those students who need such support? Relative to OWI Principle 1, at-risk students or those in need of learning or technology accommodations are even more challenged in these cases (p. 7). Therefore, the assumption that a fully online course unfolds equally for all students and that it does so entirely online does not always bear out, which requires WPAs to consider its institution’s resources and ability to support a fully online OWC before signing up its first teachers and advertising it to students.

Table 2.3 illustrates this challenge by presenting a range of contractually defined course types in terms of instructional setting for the College of DuPage, a two-year institution. From an instructional standpoint, teachers of writing need such information to make important decisions about how to manage class time and, in cases where multiple instructional settings are available for one course, about what activities might work best in what setting. Conceivably, a writing teacher could face a semester teaching just one course like FYW but be assigned a full load of four FYW classes in the form of one hybrid, one fully online, one onsite, and one Web-enhanced class. This undesirable situation is possible particularly for contingent faculty who teach at more than one institution (see Chapter 7), and it deeply affects the preparation and performance of teachers (and, subsequently, their students) faced with these differing settings.

Table 2.3. Course types defined by instructional setting(s) at the College of DuPage

|

Course type |

Instructional setting(s) |

|

Onsite |

Instruction is entirely classroom-based |

|

Fully Online |

Instruction is entirely distance-based |

|

Hybrid |

Instruction is at least fifty percent classroom-based |

|

Web-enhanced |

Instruction is at least ninety percent classroom-based |

In this example, despite the common FYW course, materials, and desired outcomes, the four different settings lead essentially to four course preparations—even though this situation would purport to protect teachers from an onerous number of separate course preparations. Consider the effect this variety of instructional settings has on faculty working conditions. For example, my contract stipulates that “class preparations for Faculty will normally be limited to three (3)” (College of DuPage, 2012). Notice that this preparation limitation is framed in terms of a “class,” but with no acknowledgment of instructional setting. So my English composition hybrid, English composition fully online, and English composition in the onsite classroom are all counted as one preparation. This unrealistic understanding of my job presents both challenge and disincentive for those who wish to teach writing in a variety of course settings where the material is delivered and addressed differently. In fact, as an extension of OWI Principle 8, which argues that “online writing teachers should receive fair and equitable compensation for their work” (p. 19), I would add that part of a fair and equitable working environment should include institutional recognition that a single class, taught in a variety of environments and/or formats must be designed, taught, and managed—or prepped—differently.

Opportunities and Challenges of OWI Settings

My early thinking about hybrids, as suggested in the anecdote that begins this chapter, revealed my sense, and maybe my institution’s sense, of hybrid OWI as being somehow an alternative or distorted version of the traditional instructional setting. This distortion colored how I initially designed a hybrid OWC. Perhaps I unconsciously assumed that I should think in terms of a face-to-face course that fit instruction into one day a week, instead of the traditional two, and then supplemented that face-to-face work with online material, ancillary to the “real” work we did in the classroom. The result is that I probably did not integrate well the various instructional settings involved in a hybrid OWC and failed to position them as equals. Jay Caulfield (2011), a teacher of educational psychology, admitted something similar in How to Design and Teach A Hybrid Course: “For me, integrating the in-class and out-of-class teaching and learning activities ... was the toughest to learn. Sometimes I still don’t get it right, yet I know it is an essential component of effective hybrid teaching” (p. 62).

I first began designing and teaching hybrids in 2007. While I think my earliest hybrid OWCs worked well, I simply was not able to see the hybrid setting in any way but relational to an onsite course, which may be the most common perspective. The final exam scheduling snafu that I described at the beginning of this chapter is an example of the degree to which I had not yet fully understood a hybrid course as existing as its own legitimate instructional setting. It also illustrates how my understanding did not necessarily align with administrative understandings of the hybrid setting. Indeed, neither was my thinking necessarily coordinated in any meaningful way with any other instructors who were designing and teaching hybrids.4 We may have talked about such things casually and informally in hallway conversation, but there was no institutional mechanism to enable teachers who taught in the hybrid setting to meet and share challenges and successes.

Honoring the uniqueness of instructional settings is crucial to successfully teaching both hybrid and fully online OWCs, and in this way they are similar: Neither should be understood as an altered or deficit version of some other instructional setting, even though onsite instruction seems continually to be upheld as the standard of instruction and the normative measure to which all other instructional settings should be compared and to which all other instructional settings should aspire. Consider how often success, retention, and persistence rates are compared across instructional settings, often with fully online instruction on the low end of these measures. Such apples-to-oranges comparisons miss the important point that individual instructional settings come with their own unique opportunities and challenges. Furthermore, the conditions under which students register for classes can be vastly different depending on instructional setting. In many cases, for example, the student who would not otherwise have time to take an onsite class may register for that course online. In fact, students who might not have seen themselves as college students or who are unprepared for college work might take a fully online OWC, believing it to be easier than the onsite version of the course. This situation can be a recipe for student failure regardless of the quality and robustness of the course itself.

Unique Considerations of Hybrid OWI

Integration and Hybrid OWI

Although this chapter focuses on the overall design and teaching challenges and opportunities shared by both hybrid and fully online writing instruction, one aspect of building a hybrid writing course is unique: integrating the face-to-face and online instructional settings. I use it here as an example of designing course time with OWI students to help readers understand the exigencies of developing hybrid and fully online courses. Aycock et al. (2012) asserted that “integration is the most important aspect of course re-design and because integration can be difficult and easily overlooked it is an aspect of course re-design that is often taken much too lightly.”

In a hybrid course particularly, focus on integration needs to be intentional and persistent, from the earliest design efforts to enacting daily teaching activities. Particularly challenging might be students’ (mis)understanding about how the hybrid setting operates, which is connected to the pervasive transactional language that surrounds hybrid course definitions and descriptions and that often works against instructors who are trying to clarify for students precisely what the hybrid setting entails. In other words, a hybrid often is defined as a course type that trades, replaces, or exchanges one instructional setting for another. For example, the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee Hybrid Learning website (2013) reads, “‘Hybrid’ or ‘Blended’ are names commonly used to describe courses in which some traditional face-to-face ‘seat time’ has been replaced by online learning activities.” Other institutional Web pages have used even more explicitly transactional language, as in this example from Aiken Technical College (2014): “A hybrid class trades about 50% of its traditional campus contact hours for online work.”5

The College of DuPage (2013) provided a preferable definition in that it is less transactional: “Hybrid courses integrate 50 percent classroom instruction with 50 percent online learning.” Even though this definition is too narrow—because, as noted earlier, some hybrids will not divide instructional time in a fifty-fifty split—it does focus productively on integration of instructional settings, rather than exchangeability between them. Even so, students in my hybrid classes often ask whether we trade classroom time for online time such that the online work must be done on Friday, in a fifty-minute block, or whenever the onsite meeting otherwise would occur. Students typically need help understanding that this block of learning time is integrated into a weekly plan and that it occurs online, perhaps distributed in chunks throughout the week. Furthermore, students and instructors alike are challenged by thinking in terms of learning time, as though each week we need to do activities online that would equate in some precise way with the amount of time we would otherwise be in the classroom. Indeed, this challenge is increased in the fully online setting where typically the instruction occurs asynchronously and no specific time is allotted to face-to-face meetings (see Chapter 3).

The transactional language surrounding hybrids probably persists because on some level instructors do need to imagine roughly how much work should occur online so that a three credit course remains a three credit course whether it exists in the hybrid or fully face-to-face instructional setting. The danger of adding too much or too little work outside of the face-to-face meeting exists. Beyond this need, any sense of a hybrid as a course type that trades instructional time in one setting for another can paint the wrong picture of how the hybrid actually works, as if a precise trade of fifty minutes per week of face-time for online time should lead to an equal, discrete, fifty-minute activity regardless of course setting.

Pedagogy and Hybrid OWI

Consider this example of a straightforward hybrid OWC: A fifty-minute, onsite writing class at University X meets Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. The equivalent hybrid OWC meets Monday and Wednesday in the traditional classroom. The Friday session has various possibilities for instructional time. For instance, it could meet in a computer classroom where the teacher and students see each other face-to-face but use the computer terminals. Or, the hybrid nature of the OWC means that the Friday time might be integrated as online learning for which students complete the work independently. In either case, the setting should be the same weekly so students can build the course structure into their schedules, keeping them on track. The CCCC OWI Committee’s The State of the Art of OWI (2011c) indicated that time management is one of OWI students’ greatest challenges (p. 10). I stress to students that they should begin from week one to organize their schedules and make allowance for sufficient time to complete online work (which likely will need more than the fifty minutes they see in the onsite class trade-off), in the same way that they block out time for when they have to attend class in person. In fact, students taking fully online classes should be encouraged similarly to block out time specifically for course work, rather than letting it slide to the bottom of the to-do list, to be completed when “everything else” is done.

Although a weekly hybrid arrangement has some benefits, it is by no means the only way to effectively organize learning time in the hybrid format. In some cases, instructors might find it beneficial, and in keeping with their personal teaching style and pedagogy, to meet face-to-face for longer periods during the course—multiple weeks in a row, for example—and then to transition to a longer phase of online time. This arrangement might work particularly well if one is looking to integrate online writing conferences into a course. As Hewett (2010) stated in The Online Writing Conference, “the one-to-one online conference is an increasingly popular, vital, and viable way to teach writing” (p. xxii). Conducting such conferences online, rather than as part of the face-to-face component of a hybrid course, helps to keep the dialogue between instructor and student grounded in textual communication—a key component of the writing course itself.6 It also affords students the opportunity to manage their time more flexibly, rather than being locked into blocks of onsite seat time. As writing instructors, we may find that we need more time with students and their writing individually rather than in the group classroom setting, especially as writing students take concepts and strategies we have introduced in the classroom and begin to apply them to produce their own, individual texts.

In relatively short order, the straightforward weekly division of hybrid learning time can morph into any number of forms. Is there a guiding principle regarding how much of a writing course should be conducted onsite and how much should be online and for how long at a stretch in each instructional setting? In a general sense, OWI Principle 5 provides important direction: Writing instructors “should retain reasonable control over their own content and/or techniques for conveying, teaching, and assessing their students’ writing in their OWCs” (p. 15). In the case of teaching a hybrid OWC, OWI Principle 5 suggested that the instructor should be making decisions about how to best arrange instructional time. The hybrid design should not be automated by some kind of institutional scheduling system in an effort to maximize classroom space usage or haphazardly designed by a department chair or WPA who does not have a developed understanding of OWI and hybrid learning, in particular.

However, institutions may seek overly simplistic efficiencies by trying to capitalize on the hybrid learning model. Administrators may, for example, take two hybrid classes that in their fully onsite formats would meet twice per week, and pair them in a single classroom: Class A meets onsite Tuesday but not Thursday, while class B meets onsite Thursday but not Tuesday. This kind of administrative control over how a hybrid operates serves neither instructors nor students, nor am I convinced that efficiencies of this kind could ever be achieved on a scale that would have any measurable impact campus-wide. The degree to which faculty must give over curricular design to a centralized scheduling system in this scenario ultimately is unacceptable, particularly in terms of course goals and pedagogical strategies for meeting those goals. There is no one “right” division of learning time in the hybrid setting since an ideal arrangement for one instructor may not be ideal for another. Actually, the impact of hybrid design on student success is an area of much needed OWI-based composition research (see Chapter 17). But in keeping with OWI Principle 5 (p. 15), arranging instructional time should be within the instructor’s curricular control, and as such can reflect his or her individual teaching style, personality, and pedagogical approaches.

Instructors wanting to explore how a hybrid writing course can be configured to best serve the students, however, probably will have to navigate a number of institutional constraints that potentially include mandates about exactly how a hybrid class must divide its time. Further, the instructor may have to sell the idea of a hybrid that does not divide its time on a weekly basis, in which case I advise presenting one’s case with particular reference to established, disciplinary effective practice where or if those practices exist. In many ways, A Position Statement of Principles and Example Effective Practices for OWI (CCCC OWI Committee, 2013), which is this book’s genesis, provides an ideal framework within which to situate individual teaching strategies.

Take the case of a faculty member who notices that in dividing her class time on a weekly basis, students are losing connection with their writing as process or they are responsible for returning to their online writing work without having accomplished much in a single weekly classroom session. Her students would seem to benefit from an extended set of classroom meetings to learn writing strategies in a real-time, onsite setting that allows for immediate interaction with peers and with the instructor. Then, having learned some strategies for invention and organization, an extended period of individualized online conferencing might seem most beneficial such that each student can apply material learned from those classroom meetings to produce a polished piece of writing. Conferencing online provides both teacher and student the opportunity to talk about the student’s writing in writing, which can help students to clarify challenges they are facing as they express those challenges in writing rather than verbally (Hewett 2015b, 2010). A particular benefit of moving the learning online at this point in a writing course is that instruction can become much more adaptive and individualized since the instructor is no longer trying to deal with all her students as a group in the onsite setting. Rather, instruction can become much more specific to each student’s needs. In this example, therefore, the instructional time for one-to-three weeks might be onsite and face-to-face. Then, the writing course would occur in a distance-based, online format for an equal period, featuring some or all of the following: asynchronous and/or synchronous online writing conferencing, online peer revision exchanges, and asynchronous instructor feedback on student drafts as they unfold.

Now let us extend this theoretical hybrid writing class design so that the week of onsite face-to-face meetings becomes a month or even two. Perhaps the hybrid writing class would meet every Tuesday and Thursday for the first half of a semester, just as a fully onsite writing course would (thus, requiring available classrooms and seats for this configuration). Then, perhaps all the work would be integrated to an online setting for the last half of the semester. This configuration still represents a 50% face-to-face/online split, adhering to at least the letter of the contractual law at the College of DuPage, for example. But will such a hybrid arrangement be supported by the administration? In most cases, this creative course design would be a hard sell in terms of seat space alone, but also in those cases where administrators are skeptical of (even resistant to) what are perceived to be “alternative” instructional settings. Like it or not, it will be incumbent on the teaching faculty member to establish sound pedagogy as the basis for dividing onsite and online time in the hybrid setting.

Perhaps, ultimately, OWI Principle 6 provides the guiding principle here, at least from the instructional perspective: “Alternative, self-paced, or experimental OWI models should be subject to the same principles of pedagogical soundness, teacher/designer preparation, and oversight detailed” in the position statement document (pp. 16-17). While hybrid writing instruction should not be understood as experimental or alternative, certain instructional designs that coordinate online and face-to-face time in seemingly unconventional ways are likely to be perceived as experimental or alternative. To that end, in Chapter 1, Hewett explains that experimental OWI models especially need to be developed and grounded by principles of rhetoric and composition. The instructor who wants to be creative with hybrid writing course design may have to demonstrate to administrators the sound pedagogy behind the design. But if the pedagogy is sound, A Position Statement of Principles and Example Effective Practices for OWI (CCCC OWI Committee, 2013) supports the assertion that hybrid writing instruction could take a number of successful forms.

Designing Hybrid and Fully Online OWI

The Special Need for Organization in OWI

Although effective organization of writing course content, assignments, grading—everything that goes into teaching writing in any setting—is important when teaching fully face-to-face, something about the regularity of the onsite meetings helps to make an onsite course feel unified and organized even when instructors have made no special design choices in this regard. The onsite instructional setting is probably the most natural for students and teachers in that both teachers and students are most familiar with it, and a potential sense of class continuity may emerge by virtue of that familiarity and the regular face-to-face meetings. A natural sense of organizational structure is not necessarily the case for either hybrid or fully online writing instruction, so the next section focuses on organizational strategies that can help both instructors and students navigate an OWC successfully. It will not surprise readers that a well-organized course is more likely to be effective than a poorly organized course, but such organization is a basic necessity in both fully online and hybrid writing courses. It is not something that will somehow take care of itself in either instructional setting, and developing a well-organized online course requires consciously thoughtful work on the instructor’s part.

Organization suggests that course objectives are laid out clearly on the LMS and reiterated (repeated, as Warnock, 2009, and Hewett, 2015a suggested) in a number of website pages throughout a syllabus and the course itself. A course divided into units, modules, or weeks is likely to benefit from having each of those divisions introduced with learning goals, ones clearly linked to general course objectives. Basic organization of this kind (ideally) will help students to understand the why of what they are doing and, in turn, provide that important opportunity for intellectual and emotional presence. I have too often heard students complain about what they perceive to be busy-work in classes—including my own. In such cases, typically I learned that I had not made transparent enough the unit goals and how those were linked to course goals. For example, if we were writing paragraphs instead of full essays or creating outlines before starting rough drafts, it might have felt like busy-work disconnected from the supposedly real work of writing that was to be the focus of the course because I had not done a good job of connecting those activities to a bigger picture. Thoughtful course organization that includes reiteration of course and unit goals throughout can help give students a sense of why those small-scale activities are important.

Figure 2.1 is a screenshot of what students see in the Blackboard LMS in both my fully online and hybrid writing courses. Course and unit-specific goals help students to understand how pieces of the course are related and how or why materials are organized the way they are.

Figure 2.1. Course goals articulated in both fully online and hybrid OWI settings

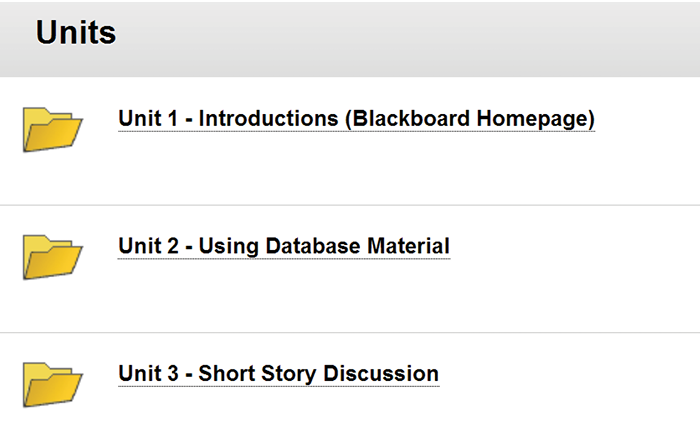

As Figure 2.2 demonstrates, instructional units can be introduced with goals that help to outline what activities will be taking place. These unit-level goals in many cases can be tied back to course goals as a way of making course organization transparent. In other words, student are invited to see how what they do in an individual week, for example, is part of a larger overall structure.

Figure 2.2. Sample unit-level learning goals statement

The goals shown in these figures are not groundbreaking nor are they exhaustive for everything that we might cover in a given unit; indeed, some students may not even read them or, upon reading them may not comprehend them sufficiently (Hewett, 2015a). However, these statements provide the basic expected outcomes for the course and, by the end of a given OWC, I hope my students have done a lot more than accomplish the basic course objectives. Making these goals clear and reiterating them for students throughout a fully online or hybrid writing course can help to provide a sense of basic organization and purpose that might be missing for some learners when they are not meeting weekly with the same group of people in an onsite setting. These goals operate as textual reminders of what we are doing and why, whereas in the onsite, face-to-face course, I more likely would provide these reminders verbally in class.

One particular element of organization that is specific to the hybrid OWC is the coordination of the face-to-face and online instructional settings. In both settings, students should feel connected to the course and should feel they are participating in one, unified course whose onsite and online settings are equivalent in importance. In other words, the hybrid writing instructor should avoid giving students the sense that they are in a face-to-face class that is merely supplemented by online materials. Similarly, the hybrid writing instructor should create the course with such organizational unity that students do not feel that they are participating in two related, but ultimately separate, courses: a face-to-face course and a fully online course. Doing so can help prevent students from experiencing such courses as more than the credit-load for which they signed up (i.e., a three-credit course should not seem like a four-credit course just because it is hybrid).

In addition to stating course and unit-level learning goals as clearly and as often as possible, another organizational strategy is to make sure that students understand how the syllabus (which lists weekly course activities and assignments) is coordinated with the course as it exists in the LMS. In my hybrid OWCs that divide time weekly, for example, I label each unit in the course the same way on the syllabus that is intended to be printed and that is designed for online presentation (e.g., “Unit 1 – Introductions”). Within each unit on the syllabus, I list days we will meet onsite and generally which readings or activities we will be doing (without being too exhaustive); additionally, I always include, in line with useful repetition, a reminder of the online component. Figure 2.3 provides a typical example.

Figure 2.3. Example syllabus showing units and online work in a hybrid OWC

When students then go into the LMS, they know to look for the “Units” area of the course where they will find units that correspond with each of the units identified in the syllabus. Figure 2.4 provides an example. Basic coordination between the course schedule as revealed in the syllabus and the online component of the class helps students to see the two pieces of the class as connected rather than as two distinct endeavors.

Figure 2.4. Example units area in Blackboard for a hybrid OWC

Of course, the surface coordination that can be achieved through clear, redundant labeling will be part of a much deeper integration of what is occurring in the classroom and online. The work that students will find within each unit reflects what we have discussed in class. Sometimes the work that students complete online will then feed into what we cover in subsequent onsite meetings, which for fully online courses has to be accomplished digitally as well. For example, in the hybrid course, using student posts to online discussion boards as conversation starters for subsequent face-to-face discussion is an effective approach. Classroom discussion does not have to start from scratch, nor does the instructor have to put forward the first idea. Seeing their online work made present in the classroom also helps students to see the mixed instructional settings of their hybrid class as deeply related. In fact, making virtual discussion into physical and real-time onsite work also helps students to see themselves as members of a class both online and face-to-face.

Coordination between the online and face-to-face components of a hybrid writing course can be demonstrated in many ways. In the end, a hybrid writing course will, ideally, feel like one learning experience. Through good integration, students will feel as present online as they do onsite.

Building Community

The need for social presence is shared by both hybrid and fully online OWI. By social presence, I mean the idea of people in a course together, even if that togetherness is virtual and not physical. Addressing presence means creating opportunities for learner engagement on the intellectual and the emotional levels. In other words, students are challenged, rewarded for creative thinking, and have the opportunity to demonstrate competency in a variety of ways. Furthermore, students need the opportunity to care about what is going on in a course. They ideally care about what they are doing but also what others are doing. They, again ideally, believe that they are part of a group of learners engaging in interesting and challenging material and they express a sense of pride in accomplishment. The course matters to them.

The term “ideal” is relative since I am talking largely about OWC design. That is, I am focused on what the instructor can control. Teachers can afford opportunities to students who in best-case scenarios will take advantage of them. But for whatever reason, some students will not take advantage of those opportunities or see the value in allowing themselves to be invested—intellectually or emotionally—in any given learning opportunity. These situations are not instructional failures on the part of the teacher (and may not be infrastructural failures of the LMS either). Writing teachers tend to provide well-organized and interesting opportunities for learner engagement and they encourage that engagement, but the teacher’s work should not be judged on whether every single student becomes intellectually or emotionally connected to one particular writing course because it is, in all likelihood, an impossibility. Hence, the notion of “ideal” is just that—a generally unreachable goal of perfection.

OWI Principle 11 called for “personalized and interpersonal communities” (p. 23) to foster student success. Experience has shown that successful writing instruction in both hybrid and fully online learning situations is most likely to occur when instructors and students are given the opportunity to be present, to realize that both teaching and learning are, as Warnock (2009) asserted, “personality-driven endeavors” (p. 179). In other words, learning writing online (or in the traditional onsite setting, for that matter) should not be a solitary, passive experience. A Position Statement of Principles and Example Effective Practices for OWI makes abundantly clear that teachers and students alike need to be supported in the endeavor to make learning to write in the hybrid and fully online formats an engaging, challenging, and ultimately rewarding experience.

Creating opportunities for presence is one of the most important design guidelines for both hybrid and fully online OWI. In addition to scholarly research in this area (see, for example, Picciano, 2001; Savery, 2005; Whithaus & Neff, 2006), ultimately my personal experience as an educator causes me to see presence as crucial across instructional settings. The need for presence is grounded in OWI Principle 11, which stated, “Online writing teachers and their institutions should develop personalized and interpersonal online communities to foster student success” (p. 23).

When instruction shifts to the fully online environment, whether in the context of hybrid and fully online OWI, the learning situation can become isolating and even alienating for some students. It may feel like a correspondence course: each student works individually through material and communicates with a virtual “grader” who remains faceless. Being present as a virtual instructor—whether through photographs, text-based conversation, quirky posts, (Warnock, 2009), or personalized and problem-centered writing conferences and draft feedback (Hewett, 2010, 2015a, 2015b)—is an important part of building overall student engagement and success.

What happens when student and/or instructor presence is lacking in OWI? Every online educator likely knows the answer to this question from experience: Students are less likely to engage; they are prone to participate insufficiently in the course; and, in the worst situations, they lose focus, fall behind and either fail or withdraw. As Julia Stella and Michael Corry (2013) indicated, “Lack of engagement can cause a student to become at risk for failing an online writing course.” They cited studies suggesting that “exemplary” online educators are those who challenge learners, affirm and encourage student effort, and who “let students know they care about their progress in the course as well as their personal well-being” (2013) To do any of this, let alone all of it, OWC instructors need to demonstrate presence in consciously purposeful ways. The hope is that when students experience the presence of others in a class with them (virtually or otherwise), they can feel supported in what they are doing.

The CCCC OWI Committee’s The State of the Art of OWI (2011c) reported that writing teachers generally see writing as both a generative and a social process. One respondent cited in the report said, “My online writing courses are intensely social and collaborative—much more so than my face-to-face writing courses. Students collaborate to produce texts” (p. 22). Educators surveyed for this report also indicated that they viewed the “ability to establish a presence online” as very important (76%) or important (23%), indicating the degree to which OWI practitioners value being present for students (p. 90). These survey respondents were speaking from their experiences and belief systems as OWC instructors. Like them, my consistent experience has been that students who are familiar with each other work better together and are more engaged in what is happening in a class, regardless of whether those students know each other (and know me) online, onsite, or some combination of the two.

Goal-Based Design

Effective hybrid and fully online OWC design often means taking what a teacher already does well in a writing class and adapting activities and assignments so that some or all of them occur online. Here is where the notion of migrating content and practices meets the needs for conscious adaptation and change for a different environment. However, as this chapter outlined earlier, the hybrid and fully online settings also present the opportunity to completely re-envision teaching and to start from the ground up, rather than thinking in relational terms alone. An effective approach to hybrid and fully online OWC design that seeks to honor both the uniqueness of the instructional settings while preserving what is already most effective about one’s own teaching is to think in terms of course goals and learning objectives: in other words, goal-based design.

Ultimately, both using what is already available and starting fresh can work together. Many instructors can name a classroom activity that seems to work well for them. In such activities, students are engaged. Class time is enjoyable for the instructor. And students produce good writing. But taking that particular classroom activity and trying to migrate it verbatim to the online setting might not be possible or advisable. The onsite and online instructional settings simply are too different in many cases. To take advantage of a good onsite activity, it is necessary to take a step backward and consider what course goal or objective is achieved with it. Does the activity do a good job of getting students to think critically or creatively? Does it get students attuned to nuances of language? Does it get students actively working with sources and evaluating information effectively? These are important course goals in many writing classes.

Once an instructor has a sense of the goals that are being achieved effectively in the onsite setting and of what seems endemic to the activities that foster student success relative to those goals, he or she can begin course design from the ground up. In other words, instructors are not obliged to work from a completely clean slate when it comes to designing a hybrid or fully online OWC, but neither should they try to reconfigure every last classroom activity so that it can exist online.

For example, suppose that an instructor who typically teaches a fully onsite writing course wants to spur students to generate ideas about a text. To achieve this goal, she has her students work in groups for ten minutes at the start of class. In designing a similar activity for the online setting, however, it is difficult—and likely unproductive—to try to duplicate the face-to-face brainstorming activity by including a ten-minute chat-based synchronous session for her online students. First, that amount of time is probably too short a time for students to get situated online and to type meaningful ideas back and forth. Second, if the brainstorming activity includes shifting to synchronous conferencing software, there also is a likely time lag for getting students together; additionally, such software—even if available on the LMS—may introduce potential technical challenges (for both instructor and student) that can inhibit full participation by everybody in class and that may not meet the access needs suggested by OWI Principle 1 (p. 7). Indeed, although I have used Web-conferencing applications successfully in my own courses, their use simply to reproduce as closely as possible what happens in the onsite, face-to-face environment seems more complicated than necessary given what it is likely to achieve.

Instead, while the goal of having her students brainstorm together remains, the teacher would do well to change the activity. For example, students could be asked to collaborate through an asynchronous discussion board or a group Wiki located within the LMS. When multiplied across the various activities that are developed for a writing course, the goal-based design approach likely will produce an online course that looks drastically different from an onsite, face-to-face course—despite the fact that they share common basic learning goals.

Aycock et al. (2008) suggested that “performative learning activities may be best face-to-face” and “discursive learning activities may be best online” (p. 26). Similarly, instructors might find in the case of hybrid writing course design, as opposed to the fully online setting, that they ultimately think about which activities work best online and which work best face-to-face. Here, “best” can be quite subjective. Depending on a teacher’s disposition and teaching style, he or she might believe that discussion is a good face-to-face activity that benefits from the dynamic, real-time give-and-take of classroom presence and non-verbal cues to engage students’ interest. By the same token, much can be said for discussion enabled online, either asynchronously or synchronously. Especially with asynchronous discussion, students who might not otherwise be eager to participate in the face-to-face environment may be more at ease joining in, not to mention that the instructor can see readily who has participated and who has not, which can enable the teacher to draw out the students who fail to participate for whatever reasons. Additionally, asynchronous communication opportunities allow students to discuss ideas informally among themselves, but, unlike an informal oral discussion, students can reflect first about their contributions. They can write, edit, revise, delete, and post, taking more time than would ever be feasible in a real-time, oral situation.

If there is any conventional lore-like wisdom regarding hybrid course design in particular, it is probably that writing-based activities occur best online and that discussion-based activities occur best face-to-face. I would like to challenge this wisdom, however, not necessarily by claiming the reverse, but by emphasizing that instructors can vary which activities they use in any instructional setting. Variety is more useful than overly prescriptive approaches that dictate that all activities of one kind or another always must occur in a given instructional setting. To that end, thinking in terms of goals to be achieved is an important step away from the sense that the job of the educator in the fully online and hybrid settings is somehow to duplicate, however imprecisely, exactly what occurs in onsite teaching.

OWI Settings Are Not About the Technology

As described above, goal-based design asks writing instructors to take a broad view of their teaching, and it inevitably leads to specific questions about the technology involved. If instructors are not somehow trying to reproduce precisely online what happens onsite and they instead consider how learning goals can be achieved in new ways, the question of which digital tools can be used most effectively to achieve those goals inevitably will arise. Considering and selecting technology and software is one of the most challenging tasks that OWI teachers face. Especially regarding teaching writing online, educators often may think that technology and pedagogy are in a tense relationship with one another. Which comes first? And which ends up requiring the majority of our energy and attention?

Hewett (2013) argued that “to let the technology drive the educational experience” for OWI is ultimately to “abandon instructional authority to the technology” (p. 204). She recommended that instructors first examine course setting (i.e., hybrid or fully online), pedagogical purpose (i.e., course type, genre, and level), digital modality (i.e., asynchronicity versus synchronicity), the desired media (i.e., text, voice, audio/video), and student audience (i.e., age, expectations, and capabilities, as well as physical disabilities, learning challenges, socioeconomic backgrounds, and multilingual considerations) before considering technology—available or desired. It is well and good for instructors to consider technology last, yet the reality remains that technology may be what is most emphasized institutionally. Often, for example, professional training and support for those desiring to teach hybrid or fully online OWCs (when such support exists) come almost exclusively in the form of IT training: how to use the latest tools in the LMS, how to master the gradebook, how to develop a test bank, and so on (OWI Committee, 2011c).

To be sure, it is hard to separate thinking about hybrid or fully online writing instruction from technology, since what seems to differentiate these settings from a fully onsite writing class is the technology. And, certainly, practical training in an LMS is crucial for teachers, but that is only one aspect of what training needs to be, as OWI Principle 7 indicated (p. 17; see also Chapter 11). There also must be ample discussion and training regarding the underlying pedagogy. A Position Statement of Principles and Example Effective Practices for OWI provided important guidance in this regard in that it asserted the primacy of pedagogy over technology. OWI Principle 2 stated, “An online writing course should focus on writing and not on technology orientation or teaching students how to use learning and other technologies.” Furthermore, it said, “Unlike a digital rhetoric course an OWC is not considered to be a place for stretching technological skills as much as for becoming stronger writers in various selected genres” (p. 11).

It is important for OWI teachers to have these OWI principles at their disposal because so often we find ourselves being asked, explicitly or otherwise, to be technology experts when we teach writing in the hybrid or fully online settings. We also are asked routinely to make good writing instructional use of LMSs or other institutionally supported technologies that are not well suited to OWI because they were not designed with writing instruction in mind.

Yet, while we always want to foreground the pedagogy of our work and not technology, there really is no escaping the fact that OWI is mediated through technology in ways that fully face-to-face writing instruction is not. In fact, OWI Principle 13 asserted that “students should be prepared by the institution and their teachers for the unique technological and pedagogical components of OWI” (p. 26). Thus, while OWI Principle 2 indicated that the writing course is not the place to teach technologies per se, the writing instructor, along with the institution, retains some responsibilities for orienting and assisting students in OWCs to use the technology for writing course purposes (p. 11). As many OWI educators probably have discovered, regardless of the setting, a student who has technical trouble tends to go to the teacher first for technology help—and with complaints.