11: Faculty Preparation for OWI

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 77983

- Beth L. Hewett and Kevin Eric DePew, Editors

- WAC Clearinghouse

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Chapter 11. Faculty Preparation for OWI

University of Minnesota

This chapter, directed primarily to those who will train OWI teachers, examines the importance of training in light of the increase of OWC offerings in colleges and universities nationwide. To this end, the chapter first situates OWI in the larger context of distance learning and identifies characteristics that distinguish OWI from other online courses. Then, the chapter identifies four principles of training teachers for OWI, called the 4-M Training Approach. Using these principles, it then addresses issues specific to helping instructors transition to OWI and offers training suggestions for addressing these issues. Finally, interspersed in the chapter are suggestions for training that involve OWI course planning documents, OWI case study, OWI teaching groups, and assessment activities.

Keywords: accessibility, association, immersion, individualization, investigation, media, migration, modality, model, morale, reflection, social presence, training, usability

As A Position Statement of Principles and Example Effective Practices for OWI (CCCC OWI Committee, 2013) noted, the increase in OWCs requires attention toward OWI teacher training and an understanding of effective practices in OWI. The fifteen principles articulated in A Position Statement of Principles and Example Effective Practices for OWI provide an excellent basis for OWI training, and two of the 15 OWI principles specifically address training:

OWI Principle 7: “Writing Program Administrators (WPAs) for OWI programs and their online writing teachers should receive appropriate OWI-focused training, professional development, and assessment for evaluation and promotion purposes” (p. 17).

OWI Principle 14: “Online writing lab administrators and tutors should undergo selection, training, and ongoing professional development activities that match the environment in which they will work (p. 28).

These principles both articulated effective practices as well as a rationale for training. Notably, the rationale for OWI Principle 7 mentioned that OWI teachers need proficiency in three areas: (1) writing instruction experience, (2) ability to teach writing in a digital environment, and (3) ability to teach writing in a text-based digital environment (p. 18). The accompanying effective practices further specified that OWI teachers need training in “modalities, logistics, time management, and career choices” as well as the technological elements of teaching both synchronously and asynchronously (p. 18). As we consider training, we must add accessibility to this list, for accessibility is the overarching principle in A Position Statement of Principles and Example Effective Practices for OWI (CCCC OWI Committee, 2013):

OWI Principle 1: “Online writing instruction should be universally inclusive and accessible” (p. 7).

While OWI Principle 1 does not address training specifically, accessibility issues in the development of accessible Web-based content have a critical implication for training. Keeping OWI Principle 1 regarding the need for inclusivity and accessibility in mind, as well as OWI Principles 7 and 14, this chapter addresses OWI training with the goal of helping those who are charged with developing OWI teacher-training programs. Because issues of accessibility are an overarching concern, this chapter begins with an introduction to accessibility relevant to training educators for OWI. Then, this chapter addresses a number of issues associated with OWI training and provides ideas that can contribute to an effective OWI training program.

To ground the training issues provided in this chapter, I use the five educational principles outlined by Beth L. Hewett and Christa Ehmann (2004) in Preparing Educators for Online Writing Instruction: Principles and Processes. These principles are investigation, immersion, individualization, association, and reflection. The principle of investigation addresses the need to “rigorously” examine “teaching and learning processes as they occur in naturalistic settings” such as the training course (Hewett & Ehmann, 2004, p. 6). Only by investigating our training and OWI practices, asserted Hewett and Ehmann, can we best understand what works and what needs to be approached differently. Immersion is an educational principle that suggests there is no better way to learn something than to be placed within its milieu; language learners are taught in the target language and writers are taught to write by writing. Similarly, learning to teach in an OWC is best accomplished in the online setting. Individualization is a key to helping the learner grasp and make use of the new information and skills being taught. It provides flexibility for the OWI teacher trainee within the structure of a training course. Just as students in OWCs need personalized and individualized attention to their writing, so do new OWI teachers need individual attention from their trainers and from each other. The online setting can be lonely, as OWI Principle 11 (p. 23) recognized by insisting that students need opportunities to develop online communities; similarly, OWI teacher-trainees need to associate with other new learners and their mentors. Providing association is about giving OWI teachers the opportunity to talk with each other—preferably while immersed in the online setting in which they will teach. Finally, learners need the opportunity for a “critically reflexive process of examining notions about teaching and learning in light of one’s actual experiences” (p. 20). Such a process is engendered in the principle of reflection, whereby teacher trainees are offered opportunities to both think and talk about their experiences, encouraged to assess these experiences and how they will or will not play into future OWI teaching. Each of these five principles is called upon in the training exercises provided in this chapter.

Accessibility

Three high-level accessibility issues and concerns are worth noting because instructors need to learn about them in training: the range of disabilities OWI teachers might encounter, accessible content, and using an LMS in an accessible manner. As well, these accessibility issues can and should be applied to OWI training environments so that instructors have full access to training materials and experiences.

The first is the suggestion to consider the range of disabilities that may affect students in OWCs, or even Web-based environments generally. Thinking about students first helps educators to understand needs students may have and how to help them. My first introduction to accessibility issues in OWI came from reading a graduate student’s dissertation on autism and online learning by Christopher Scott Wyatt (2010). Wyatt interviewed 17 autistic adults about their preferences regarding online course interfaces; all students in the study had experience taking online courses. One striking finding was the clear preference among all participants for text-only interfaces, which is to say that uses of color, video, or flashing images were distracting to most of these students and in some cases physically painful. Wyatt offered recommendations for online course design including text-only interfaces. In a similar vein, the collective authors of Web Accessibility: Web Standards and Regulatory Compliance suggested considering real people with real challenges as a way to begin thinking about accessibility issues in Web environments. They described people with such challenges as diminished motor control, loss of arms or hands, loss of sight, and loss of hearing. In such cases, individuals may not be able to access a keyboard or mouse, read the screen, or hear audio (Thatcher et al., 2006, pp. 2-3). These authors strongly suggested including disabled persons on Web design teams as a means to improve accessibility.

Web design teams often do not exist for OWI particularly, and instructors largely are on their own as they develop content. This autonomy leads to concerns about accessible content, a second high-level issue regarding OWI accessibility. Instructors may create a variety of documents and media for OWCs such as Microsoft Word and PDF documents, slide show presentations, videos, audio/videos, and podcasts. According to the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) (2012), any file delivered via the Web needs to be accessible in terms of being perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust. WCAG offers extensive details in each of these areas, but generally care must be taken to accommodate screen readers as “text alternatives” for non-text items (e.g., video and images, captions for multimedia, exclusive keyboard functionality sans mouse, avoidance of flashing images that may cause seizures, and use of style guides to help structure reading and information flow in documents). The WCAG guidelines, arising from the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), a division of the World Wide Web Consortium (the Web’s governing body), have current authority regarding Web accessibility.

For OWI teachers not trained in Web design, the list of accommodations provided by WCAG may feel intimidating, which leads to a third issue to address concerning accessibility: the use of Web-based courseware or LMS packages. An important question is whether or not such courseware systems are designed to address accessibility issues. As Chapter 8 reveals, the answer, unfortunately, is not completely. LMSs are not developed to control completely for accessibility issues, in part because they invite content contributions from authors/instructors who typically are able bodied. Instructors ultimately are responsible for making their content accessible, which means that every attachment shared on an LMS must be designed to be accessible in terms of the accommodations listed above. How is this work possible for OWI teachers, given all of the other demands of the job?

If instructors want to make their materials universally acceptable, they must learn to create/author them with accessibility in mind. Using the word processor’s “styles” for headings is one example. WCAG advised that information should appear in predictable ways, and consistent headings are one way to structure text-heavy documents. However, this information must be coded into the document so that screen readers can share the information; simply bolding or centering text on its own does not code the text. If authors use the “styles” function in Microsoft Word, for example, headings are coded automatically into documents with consistent font and style structure, enabling screen readers to share that information. Making this simple shift in authoring documents and attachments is one way to create accessible documents. Similarly, Web pages created via LMSs should make use of the “styles” function and “ALT-text” functions available in that courseware package.

Fortunately, those who design LMSs and higher education institutions are beginning to provide specific help and suggestions for accessible and universal design. At my own institution, I examined Moodle (our institution’s LMS) for any sign of accessibility suggestions. I could not find it on my own; however, when I contacted the help line, I got an answer in less than 30 minutes with links to suggestions for making content more accessible (Regents, 2014). The suggestions generally followed the WCAG guidelines in terms of adding codes to attachments that would enable screen readers to share descriptions of non-text items and document structures.

With accessibility and OWI Principle 1 in mind, this chapter now addresses specific issues related to OWI training.

Focal Points for OWI Training

Having taught writing online in course settings, tutoring centers, and academic programs for over ten years, and having conducted several training sessions for OWI teachers, I have learned that OWI training must enable instructors to air their concerns and take ownership of their online teaching experience from the very beginning. Instructors rarely come to online instruction training enthusiastically, and they often bring a healthy dose of resistance. An essential part of training involves allowing instructors to articulate their issues and concerns and then to develop suggestions that directly address those concerns. I also have learned that writing instructors—whether tutors, writing faculty, or discipline-specific faculty teaching writing—share many of the same issues and concerns about working with OWI. These issues regard four specific areas for training, a 4-M Training Approach:

- Migration, or decisions about sameness and difference with onsite instruction, is an issue of course design;

- Model, or the conceptual model or mental framework the online course is designed to convey, also is an issue of course design;

- Modality and media, or modality as the form of communication in the course—whether synchronous or asynchronous—and such media as text, visual, audio, or video, are issues of technology choice; and

- Morale, or the sense of community and “social presence” conveyed in the course, is an issue of student engagement in the OWC.

In the remainder of this chapter, I identify and address these recurring issues, and I outline proactive training suggestions to address them. Combined, these training steps allow OWI teachers to develop a design concept for OWI that they can own and tweak as they gain experience with OWI.

Migration

As I use the term in this chapter, migration refers to the design elements of OWCs, which is one choice that OWI teacher trainees need to consider as they move to the online setting. One of the interesting things about OWI is that, while it has clear distinctions from other kinds of online courses, it frequently is depicted as having equally clear distinctions from traditional, onsite, face-to-face writing courses despite many discussions about core pedagogies remaining similar. Instructors often ask, “To what extent is OWI different from onsite writing instruction?” and “Is OWI better or worse than onsite writing instruction?” These questions about “sameness” and “difference” are so core and central to discussions about OWI that they demand attention. Scholars address these questions in various ways, but one word often used to address this issue is “migration” as a focal point (see both Chapter 4 & Warnock, 2009, for other perspectives on migration and adaptation of materials, theories, and pedagogical strategies). The issue is whether onsite writing instruction can be migrated effectively to an online writing setting or whether a writing course needs to be entirely redesigned for the online space. When thinking about these concerns, it is useful to recall that hybrid OWCs, while more complex than they may appear at first, exist in both environments (see Chapter 2) and make use of similar pedagogical theories and strategies.

The word migration is used frequently to describe OWI, but not always in positive terms. For example, The State of the Art of OWI report (2011c) made this overall claim about OWI:

Teachers and administrators, to include those in writing centers, typically are simply migrating traditional face-to-face writing pedagogies to the online setting—both fully online and hybrid. Theory and practice specific to OWI has yet to be fully developed and engaged in postsecondary online settings across the United States. (CCCC OWI Committee, 2011c, p. 7)

This statement suggests that migration is a negative, or at least neutral, act—almost as if migration is a first step for instructors moving to the online space. Furthermore, in A Position Statement of Principles and Example Effective Practices for OWI, OWI Principle 3 stated, “Appropriate composition teaching/learning strategies should be developed for the unique features of the online instructional environment” (p. 12), which might seem to ignore the benefits of migration of onsite to online pedagogies. Yet, the duality of migration—considering whether it is a positive or negative strategy for OWI—can be observed in OWI Principle 4, which stated, “Appropriate onsite composition theories, pedagogies, and strategies should be migrated and adapted to the online instructional environment” (p. 14). The reality is that there is truth to both positions; as Hewett says in Chapter 1. OWI Principle 3 presents a yin to the yang in that most OWCs reflect traditional onsite writing pedagogy, but also that OWI training must prepare instructors for the differences of the online teaching space and potentially lead to new theory for the practice.

On the one hand, many scholars support the notion that OWI shares much in common with traditional, face-to-face writing instruction, and that writing instructors wanting to teach online do not need to start completely from scratch. Scott Warnock (2009) made this point clearly in Teaching Writing Online, where he prominently suggested that teachers migrate their face-to-face pedagogies to online environments. He expressed that he disliked the cautionary tales shared by some scholars that techniques used in the onsite classroom may not translate well to online environments. Indeed, Warnock suggested that “these types of cautions plunge new teachers immediately into a zone of uncertainty, where they may feel there is too much to overcome to begin teaching online” (2009, p. xiii). It is true that many instructors freeze at the initial thought of teaching online if it requires rewriting or rethinking every aspect of their teaching. Warnock suggested that teachers should find their core values and work on manifesting those into the online space, and that is, indeed, good advice. Nonetheless, Jason Snart, in Chapter 2, further advised that OWI teachers carefully adapt their writing instructional theories and strategies when migrating them online.

On the other hand, there are unique elements of online spaces, such as the text-only environment most often found in asynchronous settings (see Chapter 3). A text-heavy environment is a drastically different environment from the visual and auditory environment that exists in onsite settings. Hewett (2010, 2015b) acknowledged the challenges of text-based settings in The Online Writing Conference: A Guide for Teachers and Tutors. She demonstrated ways that conferencing by text can challenge students’ reading skills and teachers’ writing practices, and she theorized that semantic integrity (i.e., fidelity between the intended message and the inferred meaning) not only is possible but necessary to strive for in OWI. In Reading to Learn and Writing to Teach: Literacy Strategies for Online Writing Instruction (2015a), Hewett further theorized that students need to review and strengthen their reading skills for the cognitive challenges that OWI presents, requiring teachers to rethink their writing strategies for this audience. Warnock (2009) and Hewett’s (2010, 2015a, 2015b) positions appear to represent the yin and the yang of OWI Principles 3 and 4.

Hence, concerning migration and OWI, the answer is “both/and.” Instructors both can borrow strategies from onsite, face-to-face pedagogy and continue to adapt and tweak them uniquely for the online environment. Accepting this reality is a bit like straddling a line between sameness and difference: One foot needs to be firmly grounded in writing pedagogy and theory; the other needs to be grounded in online pedagogy. Similar arguments have been made about computers and writing, in which scholars both doubted and celebrated the possibilities of computer technology as they intersect with writing pedagogy. I am fond of citing Cynthia Selfe’s (1989) mantra that “pedagogy must drive technology,” which is a major theme in Creating a Computer-Supported Writing Facility: A Blueprint for Action. In this book, Selfe urged instructors to plan their pedagogy first and integrate technology later, and she adamantly stated that learning objectives need to lead and guide any technological use of computers in the classroom. This advice is repeated in countless treatises of computer-supported pedagogy (Barker & Kemp, 1990; Breuch, 2004; Galin & Latchaw, 1998; Harrington, Rickly, & Day, 2000; Hewett, 2013). This same sentiment is true for OWI: Our pedagogical principles remain strong and consistent, but our techniques and methods may be adapted to suit the online digital environment. In terms of migration, OWI does not operate from a radically different set of pedagogies or ideologies—although new theories may be needed—for it is firmly rooted in writing and composition studies. Yet, OWI teachers need to be open to the nuances introduced by the text-heavy nature of the digital environment.

Training Exercise on Migration

Keeping in mind the five educational principles of investigation, immersion, individualization, association, and reflection, one training exercise on migration might involve a teaching philosophy statement oriented toward OWI. Teaching philosophy statements are an excellent starting point for any OWI training for they ask participants to articulate their pedagogy first and then specify how they might practice that pedagogy through OWI. They also help instructors understand that they can and should exercise control over how they approach OWI. This exercise also is a foundation for professional development in OWI, as instructors can return to and adjust these statements as they become more seasoned OWI teachers.

The example training session, outlined below, engages the training principles of investigation, reflection, and association. It requires teachers to (1) outline key principles that guide one’s teaching philosophy and (2) consider how uses of technology might influence or enhance that teaching philosophy.

In completing this activity, it is important to allow people time to hear how others are reconsidering writing instruction in light of OWI so that they may model for and teach each other about their concerns, anxieties, and positive anticipation of this move to the online environment. In the spirit of immersion, trainers can cement the value of this exercise by conducting it in either the asynchronous or synchronous online modality depending on the institution’s selected LMS. Trainees can use text in the LMS online discussion board to get a feel for being in the “student” seat or they could create a short video of themselves talking about their statements and guiding principles; these, too, could be posted online to the LMS.

Training Activity

- Write a brief, 200-word statement to articulate guiding principles that are critical to your writing pedagogy in onsite, face-to-face classrooms. Examples might include such principles as “student-centered writing pedagogy is critical to the success of a writing class” or “writing process is foregrounded in every assignment.”

- Then, write another 200-word statement to articulate how teaching online writing can enhance or mesh with your principles. For example, in terms of student-centered writing pedagogy, you might consider ways online technologies could help foster the goal, such as “students can easily share their writing with one another through electronic means on discussion boards or shared websites.” In terms of writing process, you might discuss the use of technologies that allow for visualization of writing process, such as the integration of “comments” and “track changes” tools common to many word processing programs.

- Discuss in small groups what you are learning about your onsite writing instruction principles and how you imagine they do or do not work in the online setting.

Model

Model is the second focal point for training, and it also is an element of design with which OWI teacher trainees should become familiar; they need to understand issues of model in order to make appropriate choices in developing their OWCs. Although there are similarities between online and onsite writing instruction, the text-heavy, digital environment of most asynchronous OWCs requires a different set of expectations regarding the “classroom,” as the discussion of hybrid settings in Chapter 2 clearly demonstrates. When synchronous interactions are not available and audio/video rarely is used, what does a text-heavy class look like? How does it function? What are the key activities? How does grading happen? These questions all address issues of conceptual or mental models of the OWC, and interestingly, these questions are very similar to questions that address usability, an interdisciplinary study of how people interact with designs and technology.

Usability studies address how people interact with Web interfaces—often for the first time—and OWI training deals with a similar phenomenon of teacher adaptation to a Web space. In fact, much work in usability studies arose from computer science, specifically interface and software design (Nielsen, 1993). Today, the field of usability studies has grown to include intersections of several disciplines such as psychology, computer science, ergonomics, technical communication, design, and anthropology (Redish, 2004; Quesenbery, n.d.). Usability studies involves the examination of user perspectives to inform design processes, and it is especially concerned with ease-of-use and the ways in which technology helps users achieve their goals (Rubin & Chisnell, 2008, p. 4; Barnum, 2011). Many scholars have further defined usability by articulating attributes such as learnability, satisfaction, effectiveness, efficiency, engagement, and error tolerance (Nielsen, 1993; Rubin & Chisnell, 2008; Quesenbery, n.d.). At its heart, usability is concerned with how people interact with technology.

This concern intersects nicely with OWI in that instructors often worry about how technology affects their instructional goals. Usability studies also intersect with OWI training in that it directly addresses—and values—the anxiety that users may experience in digital environments. One might argue that when taking a course online, both instructors and students experience a degree of anxiety. Much of this anxiety can be attributed to unclear expectations both about how the course will function and student and instructor responsibilities.

It is here that the idea of a conceptual model or mental model can be extremely helpful in training for OWI. By conceptual model, I mean an understanding of the expectations of how something works. As Donald Norman (1988) explained in The Design of Everyday Things, good design has to do with how we understand what to do with objects (p. 12). Key to his theory of design is the idea of a conceptual or mental model, which he defines as “the models people have of themselves, others, the environment, and the things with which they interact” (p. 17). Using examples of everyday objects, Norman explained how designs can simplify or complicate our actions, resulting in various degrees of satisfaction. One of my favorite examples is his examination of doors in public places. He wondered “how do we know to open the door?” and explained that cues about the design help us understand whether to push or pull a door open (p. 10). For example, I have often observed doors in public buildings that have a large metal plate in the center of the door with a curved handle at the bottom of the plate. The curve, according to Norman, is a visible and physical cue that suggests that users must pull the door open. Without it, users might see the plate and think they must push the door to open it. The point is that design elements can communicate a model of use or intended action. In short, Norman said that conceptual models “allow[s] us to predict the effects of our actions” (13). Jeff Rubin (1996) further explained that conceptual models often are described in terms of metaphors that help users interact with a product or interface (for example, the activity of deleting a document on a computer desktop is symbolized by a trash can icon). Rubin pointed out that conceptual models are always operating, although they are not always explicit. If we can tap into our conceptual models, we have a much better chance of understanding a design and interacting with it successfully. Troubles arise when developer and user conceptual models do not match.

Conceptual models of OWI are always operating, much like Rubin suggested. Unfortunately, time and time again, I have observed that instructors and students bring different conceptual models to the OWI experience, and these clashes often result in attrition and/or student failure in the course. One of the most common clashes I have seen occurs when instructors create an OWC that models a face-to-face class, but students come to the OWC expecting it to be a self-paced, independent study. That is to say, students might expect an OWI to be flexible, negotiable, with a deadline for work at the end of the semester, rather than a large class experience that happens on a weekly schedule online. When this clash happens, students may disappear for weeks at a time and surface when they are ready to complete the work. By the time students realize the consequences of these actions, their only choices might be to drop or fail the course. Keeping this possibility in mind, instructors need to learn to communicate clearly about the overall structure and model of the course before the course even begins. This kind of communication will help ensure that students’ and instructor’s conceptual models agree and will guide the student’s work. As Norman (1988) and Rubin (1996) revealed, successful use is achieved when user and designer conceptual models match one another. The same goal is true for the OWI experience: Student and instructor understandings of OWC model must match.

When this idea of conceptual model is applied further to OWI, it is useful to think about different ways OWC models could be structured in terms of schedules and interactions. To illustrate, three popular models for OWI that I have encountered include an independent study model, a workshop model, or face-to-face class model. Each model structures course schedules and interactions differently.

Independent Study Model

An independent study model suggests that individual students take the online course essentially as a one-to-one interaction with the instructor, with no interaction with other students or larger group. The course might be set up with a reading list, specific writing assignments, and deadlines for specific assignments. It might have a great deal of flexibility depending on the schedule constraints of the instructor and student involved; in fact, the instructor and student could refine timelines for work continually and as needed. The conceptual model of an independent study reflects a great deal of flexibility and an expectation that the student will have direct and frequent interaction with the instructor. This model essentially is similar to the correspondence course model that characterized distance education courses for decades. While it seems archaic, I mention this model because it is often the dominant conceptual model that students bring with them to online courses. Many students sign up for OWCs because of the flexibility an asynchronous course offers (CCCC OWI Committee, 2011c). They might come with the expectation that they can complete the course on their own time.

Registration systems are an important factor in providing information to students about the models used for OWCs. It is helpful to provide detailed information about the course wherever possible. For example, at our institution, we have a Course Guide that allows instructors to provide detailed information about the courses they teach. If the course is online, information about that format can be included. It also is helpful if a syllabus or note from instructor can be shared or accessed on the registration site.

Workshop Model

A second model, the workshop model, might create a structure for on-going interactions to occur with instructors and between/among students. A workshop model might be structured around key events that help students practice writing, work in peer review groups to receive feedback on their writing, and revise their work. There are many ways that workshops could be organized; my favorite example of an online writing workshop is from Gotham Writers’ Workshop, an organization in New York City that offers hundreds of OWCs for a variety of purposes and contexts. Gotham structures all of their OWCs around sharing individual writers’ work, much like a creative writing workshop. They use a strong metaphor to communicate their workshop model, which they call “the booth,” which describes the activity of peer review. They visualize the OWC as authors and readers “sitting down” to talk with each other about their work. As it plays out in their online courses, the booth is an interface in which writers copy and paste their work into a split screen. The top of the screen is the author’s work, and the bottom of the screen is a space for multiple reviewers to comment. Time in the booth is scheduled carefully through a calendar in which authors meet with reviewers on certain times and dates. Activity in the booth is made visible to the entire class, very much like a creative writing class might handle turn-taking of authors on the hot seat getting review feedback from the rest of the class. In this conceptual model, the booth—workshopped writing—is the primary activity of the course. A similar concept, but different resulting interface, would be the Colorado State University “Writing Studio,” which provides students and instructors with the ability to create “rooms” in which they can organize whatever writing activities they wish (Writing@CSU). Like “the booth,” the “Writing Studio” carries with it a workshop metaphor in which writing would be reviewed and revised. The studio offers even more robust opportunities for flexible learning environments for instructors and students.

Face-to-Face Writing Class Model

A third model might be simply a face-to-face writing class. That is to say, an instructor might say “I want to teach my online class exactly the same way I teach my face-to-face class.” This kind of model fully embraces the idea of migration”of face-to-face pedagogies to the online space, which often means that primary activities of the online course involve discussion-based activities organized around assigned readings, peer review workshops, or other course activities. This model implies that online discussions and forums will be key and central to the course, affirming the idea that online experience will be text-intensive. Often, this model requires that all students participate in all discussions, thus creating a heavy reading load for the instructor and students alike (Griffin & Minter, 2013). An important element of the face-to-face model for OWI is the expectation that the course works on a shared schedule involving all students. That is, it is not an independent study in which students can take the course at their own pace. Instructors using this model must consider how the course structure and activities, although migrated, need to be adapted (see Chapters 2 & 4) such that the affordances of the online setting are used fully. OWI teachers should set clear expectation that students will complete assignments and activities as an entire class using the same timeline, and appropriate technologies must be available at the right times to support these activities (e.g., assignment drop box, online discussion forums, synchronous chats, posted reading materials, and the like).

Training for Conceptual Models

In terms of training, integrating different conceptual models into OWI training is a surprisingly fun and innovative exercise. The following exercise is a case study and discussion exercise that engages the training principles of investigation, immersion, and association. Specifically, the exercise asks instructors to identify the possible conceptual models of OWI in the case. The provided case study presents a clash between a teacher and student’s understanding of an OWC’s conceptual model.

Training Activity

Read the following case study about clashing conceptual models.

Two weeks prior to the end of a summer session, a graduating senior in a technical and professional OWC received an email notice from his instructor that he was failing the course. The news was a big surprise to the student. The instructor noted that the student was failing the course because he did not turn in two major assignments, nor did he participate in several required online discussions throughout the course. The student’s reaction was to ask, rather informally and somewhat flippantly, whether the instructor could please cut him a break; he was at his family’s cabin for summer vacation, but he needed the course to graduate. He asked the instructor if he could turn in the necessary assignments in one bundle, and would the instructor accept the work? The student suggested he would be happy to do whatever was required to finish the course. In receiving this request, the instructor’s initial reaction was to fail the student anyway because the student did not abide by the syllabus requirements. In fact, the student totally disregarded the syllabus requirements by failing to participate in weekly activities and assignments, clearly communicating that he was making up his own rules.

Discuss the following questions with your peers in your online discussion board:

- How did the conceptual models of this OWC vary between instructor and student?

- Was the student’s disregard for the rules of this online course a reason to fail him and delay his college graduation? Why or why not?

- In what ways, if at all, do issues of inclusivity and access come into play with this case?

- What would you decide as an instructor in this situation?

- What would you do to prevent this situation in future OWCs?

Modality/Media

A third focal point important for OWI training is combined notions of modality and media, which address crucial choices of technologies for OWCs. In OWI, modality and media are defined somewhat narrowly. Connie Mick and Geoffrey Middlebrook considered the modes of synchronicity (real time) and asynchronicity (delayed time) in Chapter 3. By media, OWI literature tends to mean the kind of delivery formats that are used for course content such as text, audio, video, or other media (see Hewett, 2013, for example). I discuss these items in the subsections below with the focus of teacher training.

First, however, it is helpful to note the rich connections that OWI should share with digital rhetoric and notions of multimodality, particularly given the exigencies of Chapters 14 and 15. Although mode, modality, and media have been defined somewhat differently for OWI and digital rhetoric, multimodality is an important development in writing studies that intersects with OWI and that should enrich an understanding of teaching writing online. Multimodality has received attention in composition studies as a way to expand understanding and definitions of writing. In Remixing Composition: A History of Multimodal Writing Pedagogy, Jason Palmeri (2012) noted similarities between multimodal composing and process pedagogy in composition. He asserted that composition has always been a multimodal endeavor, integrating images, text, and speech in ways that contribute to the writing process (p. 25), and he traced the history of composition to demonstrate multimodality. We see even more explicit treatment of multimodality in Writing New Media, in which Anne Wysocki (2004) asserted that “new media needs to be opened to writing” (p. 5) and that multimodal compositions allow us to examine the “range of materialities of text” (p. 15). The Writing New Media collection illustrated how writing instructors can integrate writing assignments that encourage students to explore and/or create visual, aural, and digital components of their work to enhance the message they want to communicate. Similar examples are found in collections such as Multimodal Composition (Selfe, 2007). While these connections illustrate and even justify the view of writing as multimodal, few of these sources address writing instruction as a multimodal endeavor. Instead, these sources are focused on helping students create multimodal documents and expand definitions of writing. We might take some of the same lessons of multimodality and apply them to OWI from the teaching perspective.

Synchronous or Asynchronous Modalities

Deciding between the synchronous and asynchronous modalities is one of the first choices an OWI teacher must make when offering a hybrid or fully online OWC, as Chapter 3 describes.

New OWI teachers need to understand that choosing to use a synchronous modality for an OWC means that students must be present (via the Web) at the same time, and the course is scheduled to meet for a regular weekly time and day(s). This modal choice supports the idea of a discussion-oriented writing class, in some ways similar to a traditional face-to-face format. Synchronous courses would require the use of “real-time” conferencing technologies that afford simultaneous audio and text contributions. Webinars are an example of a synchronous modality in which speakers share information and participants speak or write comments or questions; if written, they use chat room or text messaging technology. Images and documents also can be shared during synchronous sessions, and sometimes they can be edited simultaneously. Small groups could be set up to have group chats that supplement course material.

OWI teachers may have a choice in whether to develop a synchronous OWC, although often the LMS dictates their course modality. In making a choice, OWI teachers should consider the advantages and disadvantages of synchronous OWCs. One advantage to a synchronous OWC is the flexibility offered in terms of place and space; students and instructor can participate from any networked computer with the appropriate technology. Another advantage is that a synchronous course immediately communicates the idea that regular attendance and presence are necessary in order to participate, thus removing some of the barriers regarding expectations associated with independent studies or other asynchronous models discussed earlier. A third advantage is the ability to have live question and answer sessions with students, thus providing an opportunity to clear up any confusion about material, assignments, or activities in the class. As well, the synchronous modality has the potential to reinforce the sense and presence of a learning community (rather than individual, asynchronous contributions). One disadvantage of choosing a synchronous OWC regards access. Technological capabilities of synchronous sessions may not always be consistent; sometimes synchronous technologies cannot support a large number of participants at one time. Students may also have a variety of network connections, as Chapter 10 discusses, that may not be sufficient for the synchronous technologies even those that are mobile (see Chapter 16).

In contrast, OWI teachers need to understand that an asynchronous OWC would be offered in a “delayed time” format using non-real time technologies that allow students to participate at any time, around the clock. An asynchronous OWC might provide materials on a course website for review such as presentations, readings, discussion questions, videos, or podcasts. After reviewing material, students might be expected to participate in weekly (or more frequent) online discussions, quizzes, or group work to reinforce what they have learned. Writing assignments might be turned in via a drop box, and instructors would review the material and provide comments individually to students online. Asynchronous comments might be text-based, audio-based, audio/visual, or both. In sum, the asynchronous modal choice reinforces the idea of individual responsibility and drive to participate in an online learning community.

Asynchronous OWCs offer many advantages that OWI teachers need to think about, some of them similar to synchronous courses. Like synchronous courses, flexibility is an advantage for asynchronous courses in that students can participate via distance. However, in asynchronous courses, students participate in their own time rather than a regularly scheduled time. Another advantage of asynchronous courses is that the delayed-time format allows students to think through their contributions, and often students use that opportunity to review and even edit their responses before posting. Some disadvantages of the asynchronous modality are that the sheer volume of textual contributions might be overwhelming and even disengaging for students (as well as their teachers; training should therefore address time management for both). Care needs to be taken to contain reading loads, and one way to address that concern is to make more use of online student group contributions rather than whole-class contributions and to not grade every interaction, as Warnock notes in Chapter 4. Another disadvantage of the asynchronous format is that students need to be highly disciplined to follow deadlines. The absence of a regularly scheduled class may be difficult for some students, and the asynchronous modality for an OWC may convey a stronger sense of flexibility than actually exists.

Whatever choice of modality an instructor makes, there no doubt will be a transition to thinking about “making meaning” in that modality. An important concept in further understanding both modality and shifts in modality is affordances, or what Gunther Kress (2012) called “the material ‘stuff’ of the modality (sound, movement, light and tracings on surfaces, etc.)” (p. 80). He suggested that affordances are “shaped and reshaped in everyday social lives” (p. 80). Affordances are discussed similarly by Norman (1988), where he suggested that affordances manifest in the physical characteristics and capabilities of objects (again, we might reference the curved handle on a metal plate that forms a door handle; the curved handle affords users to pull the door open). Continuing this idea of physical or material characteristics, we also might understand affordances by reflecting on Lev Vygotsky’s (1986) discussion of tools. In Thought and Language, Vygotsky explained affordances as a way to understand “tools that mediate the relationships between students and learning goals” (Castek & Beach, 2013, p. 554). Vygotsky’s work often is used to support activity theory, a framework that addresses ways different tools mediate different kinds of activities and resulting meanings (Russell, 1999; Spinuzzi, 1999). Taken together, we might see the synchronous and asynchronous modalities as each having its own “affordances” that support different kinds of meaning making activities. In the next section, I address the OWI counterpart to modality—media—and the opportunities various media present for OWI teachers.

Media: Text, Visuals, Audio, and Video

In OWI, media are the ways through which the learning occurs, not in terms of specific software but in terms of alphabetic text, still visuals and images, audio recordings, and video recordings with and without sound. These media can be used singly or intertwined; digital rhetoric often calls these New Media and their use makes for multimodality. One immediately might think of “tools” in reference to media, or the affordances of material technologies such as online discussion forums, text-based synchronous chats, audio messages, or video chats. But before thinking about tools, it is important to think through media choices more fundamentally in terms of writing pedagogy, which includes teaching goals and strategies, rhetoricity (as Chapter 14 addresses), and the media themselves.

In Writing New Media, Anne Wysocki (2004) asserted that “new media needs to be opened to writing” (p. 5) and that multimedia compositions allow us to examine the “range of materialities of text” (p. 15). The Writing New Media collection illustrated how writing instructors can integrate writing assignments that encourage students to explore and/or create visual, aural, and digital components of their work to enhance the message they want to communicate. Similar examples are found in such collections as Multimodal Composition (Selfe, 2007) and Remixing Composition (Palmeri, 2012). Palmeri (2012) noted in particular that composition has always integrated a variety of media such as images, text, and speech, and in ways that contribute to the writing process (p. 25). He advocated the inclusion of various media in composition pedagogy so that students have a broader understanding of the composing process.

These connections illustrate important points about the value of media in writing instruction. For example, including various media can enhance the message of communication, and such inclusion also can help students appreciate and more clearly understand composing processes. In a similar fashion, these lessons can be applied to OWI, which is to say that instructors also must consider the value of multiple media for OWI. For example, integrating multiple media allows OWI teachers to enhance instruction and clarify messages or learning objectives in an online setting; reach students with various learning styles; and make use of the technologies that mirror uses students experience in social interactions, game playing, and the work world. These benefits represent “flexibility in use,” a point stated in the justification for OWI Principle 1 regarding inclusion and access and that addresses the variety of preferences and abilities students bring to an online environment (pp. 7-8). The use of multiple media additionally may provide alternative perspectives for students to engage with course material and assignments.

Certainly, different material aspects afford different kinds of meaning-making activities. Applied to OWI, the media choices commonly available provide OWI teachers with a myriad of options involving textual, visual, audio, and video/multimodal tools. The rest of this section details possibilities for OWI in each of these areas. An overlying assertion I forward is that the field of writing studies is filled with accounts of innovative, multimodal writing pedagogies; however, rarely are these accounts placed in the context of OWI. I argue that we can take these insights and connect them more explicitly to OWI.

Text

OWI is characterized as being “text heavy” due in part to the discussion-oriented nature of most OWCs. Alphabetic text, a visual medium unless given shape by Braille or sound by screen readers, is the primary means of communication between students and teacher and among students in contemporary OWI. That prevalence may be an issue of cost or of access, as this book discusses, but often it is not a matter of teacher’s choice in that the LMS is developed with text-focused affordances. This textual focus is not a bad thing as it appropriately requires reading and writing literacy skills for a writing or writing-intensive course. Tools that make use of text involve discussion boards, chats, text messaging, email, blogs, Wikis, or course Web pages. OWI teachers need training that includes a rhetorical understanding of these tools, pedagogical uses of them, and familiarity with the technology that engages them. When it comes to text as a medium, it is the writing practice that enhances the writing itself.

A common example of a text-based activity would be a discussion (or message) board, an activity often used in OWCs. Rhetorically, discussion boards allow students to practice writing arguments as well as examine reader responses and perspectives. Discussion boards can be used to support large class discussions about required readings, large class discussions about writing exercises, and small group exercises such as peer review. Typically, an instructor posts a prompt about course material, and students “reply” to the prompt, resulting in one individual message per student; discussions become interactive and more meaningful when students also are expected to respond to each other. The resultant writing practice leads students to produce many more words than they might have otherwise (Warnock, 2009). Online discussions also can be led by students or can be limited to student groups. In any of these formats, discussion prompts are posted, and students respond to the prompt in writing at different times (delayed time).

Despite the prevalence of online discussion boards, it is important to understand that students may not know intuitively how to participate in an online discussion—and instructors may not intuitively know how to mediate (or evaluate) them. Training new OWI teachers to mediate online discussions is one issue that Warnock addressed in Chapter 4 and in Teaching Writing Online: How and Why (2009). One instructor shared with me his strategy for structuring online discussion forums. First, he outlined expectations for discussion prompts that included the following elements: (1) the response must directly address the prompt or query, (2) the response must be completed within a word limit (to be determined based on the exercise), (3) the response must include at least one reference to the reading in question, and (4) students must respond to one other student’s contribution. This instructor also included a simple, clear 5-point grading structure for online discussions based on the four requirements of the discussion, which clarified for students that these discussions were weighted in the course and were not meant to be personal responses to the readings. This structure meant that the instructor graded each and every response from students—a tall order in an OWC and one that training should consider and debate given the WAC principle that not all writing needs to be graded or formally assessed. However, given a structure like this, perhaps online discussions would be used sparingly, such as once a week rather than two or three times a week.

Another example of text-based activities occurs in chat rooms, a synchronous technology that allows participants to contribute to the same, real-time discussion in a textual environment. Text-based chats may be set up for a large group in a synchronous class setting or in small groups. In either case, the students basically interact about a topic using real-time text messaging. Students can use chats for specific purposes such as discussing a reading, or coming to a group decision, or completing an activity assigned for class. One advantage of textual chats is the sense of community that often develops as students interact with one another. In OWCs that otherwise may be asynchronous, students can miss opportunities to talk with their classmates in real time. Chats sometimes feel informal and encourage informal discussions that students appreciate. Another advantage is that chats can be archived; if students completed important work during a chat, they often can save the archive of the chat for their record (or teacher’s record) towards longer written products (see Chapter 4).

Blogs (Weblogs) and journals are other venues that use text in OWI. Using blog technology, instructors can require students to create and maintain their own blog throughout a writing course. The blog software in an LMS typically catalogs entries in reverse chronological order; blogs also afford comments from readers about individual blog entries, in effect creating a “dialogue” among readers. Blogs also afford Web structures; students can create additional links to Web pages that afford students the opportunity to create Web pages for different writing samples. Wikis are another text-based tool designed to create collaborative, living, Web-based documents, but they can be tricky in that often only one writer can work in the Wiki at a time, creating the need for a way to signal other students that the Wiki is open. Instructors have used Wikis to encourage small and large group discussion and projects. Another text-based technology is the OWI Web course page itself—typically located in the LMS—in terms of the textual instructions and material offered by the writing instructor.

As discussed earlier, while there are advantages to a heavy-textual orientation for students, such as increased writing practice, there are also key drawbacks, such as a sense of being overwhelmed by text and experiencing tedium from reading and responding to countless prompts. OWI teachers may find themselves feeling equally overwhelmed with their efforts, which June Griffin and Debbie Minter (2013) called the “literacy load” in keeping with the other loads that teachers carry (see also Chapter 5). Therefore, OWI teachers need training to determine how they can manage this especially heavy literacy load, their own reading of student writing in particular.

Training OWI teachers responsibly would include such recommendations as necessary to make text-based experiences manageable from a sheer reading perspective. High volumes of text on a screen lead to low levels of engagement with text. Research from usability studies provides useful insights on this point, specifically results from eye-tracking studies on how people read online. Jakob Nielsen (2006) asserted, for example, that many studies confirm an “F-Pattern” of reading on the Web in which readers start in the top left-corner, read horizontally, then read down and horizontally at faster increments. Essentially, the F-Pattern suggests that readers on the Web read less as they go along. Eye-tracking research confirms that readers are looking for textual cues, such as headings and key words, and that readers do not tolerate excessive text on the screen (Barnum, 2011). When we consider these confirmed reading habits, we see the importance of making text clear and concise, and as minimal as possible.

To this end, OWI teachers need training in how to make their text readable and manageable. OWI teachers also need training in writing for students, however, as students may struggle themselves with the high literacy load of OWI. A Position Statement of Principles and Example Effective Practices for OWI (CCCC OWI Committee, 2013) repeatedly mentioned strategies for clear textual communication, many of which align with technical writing and Web-based writing principles. Some suggestions are found in Effective Practice 3.3, which suggested the following suggestions for OWI in textual modality:

- Writing shorter, chunkier paragraphs

- Using formatting tools wisely to highlight information with adequate white space, colors, and readable fonts

- Providing captioned graphics where useful

- Drawing (when tools allow)

- Striking out words and substituting others to provide clear examples of revision strategies

- Using highlighting strategically (pp. 12-13).

These useful suggestions for writing to students in text-based online settings mesh well with other published recommendations for Web-writing and technical communication (see, for example, Hewett 2015a). For instance, in Letting Go of the Words, Janice Redish (2007) offered suggestions for Web-based writing that address typography, color, use of space, and concise writing. One section of her text is actually called “Cut! Cut! Cut! And Cut again!” (p. 132) to reinforce the idea that Web-based writing needs to communicate concisely and clearly. Redish also advised using direct language and thinking strategically about communicating a core message on every page, and this advice resonates with stated effective practices of OWI to use “direct rather than indirect language” (p. 12).

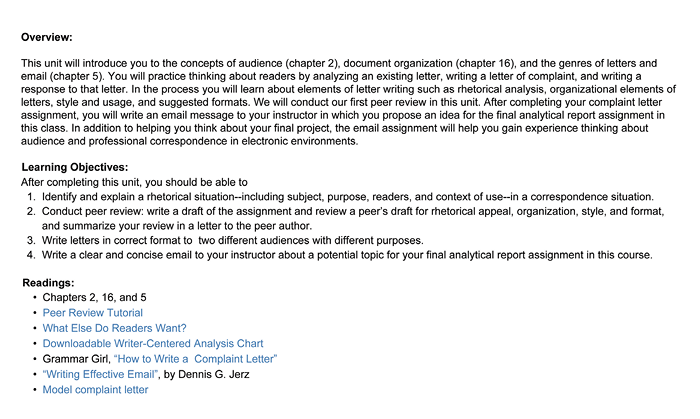

Keeping manageable text in mind, I strongly support training OWI teachers to engage the OWI principles regarding clear and linguistically direct language (part of what Hewett [2015b, 2010] calls semantic integrity). I would add that clear and consistent heading structures also are important to achieve textual clarity in any text-based materials provided by instructors. For example, in our upper-division online course in technical and professional writing, we have structured the course around eight units; each unit has a consistent structure including two main sections: (1) “Read me first” (a section including attachments with an overview of the unit, required readings, and any supplemental materials) and (2) “Activities and assignments” (a section including functions and/or links to discussion forums, assignment drop boxes, Wikis, or blogs). Chunking each unit into these main sections helps students understand the expectations for each unit. An important part of the “Read me first” section is the “overview,” a Web page document that provides an introduction of the unit, its learning objectives, and instructor comments about what the unit entails. We have found the “overview” very important as a communication vehicle for students, and we also find that consistent heading structures are imperative. We include the following headings in each unit “overview”: Introduction (comment on topic, subject matter, and its importance to the course), learning objectives (specific to that unit with connections to previous and/or future units), readings (the instructor’s comments about readings and access can be included here), and assignments and activities (any specific directions can be included here). Figure 11.1 provides an example.

The information in the overview shown in Figure 11.1 provides students with a blueprint about the subject matter and rationale for each unit and its readings, activities, and assignments. Additionally, it aligns with the guidelines of OWI Principle 1 (p. 7) in its uses of “styles,” numbers, and bulleted lists that are internally coded for screen readers.

Figure 11.1. Sample overview of an OWC unit.

Visuals

Teaching online writing through the Web affords the possibility of including many visuals that can supplement OWI. Visuals also use eyesight; they can be still images such as photographs, diagrams, tables, illustrations, drawings, or other graphics. Training OWI teachers about using visuals well requires some understanding of their relative advantages and challenges for students. Teachers need to learn how to employ visuals in their teaching such that students of all learning styles and abilities can read them; this use typically means providing a text-based caption and, for complete access, a thorough description of the visual.

Students, on the other hand, need to learn both how to read visuals provided by their instructors and to engage and use visuals in their own writing even when it is text-based essay writing. As discussed, many instructors have considered how to help students learn to integrate visuals into their writing, enabling them to explore multimodal aspects of writing (see, for example, Wysocki, Johnson-Eilola, Selfe, & Sirc, 2004). Many online supplemental sites now have a variety of visual materials including charts, graphs, animations, photos, or other images related to writing from which students might choose.

However, an even more immediate use of visuals for purposes of OWI is for students to learn how to visualize writing. Two specific uses of visuals and for which OWI teachers may be trained are well suited to OWI: (1) idea maps that outline writing processes and (2) annotated writing samples.

Idea maps are an often used technique in traditional face-to-face courses to help students outline a writing process or to visualize brainstorming ideas. Idea maps are an assignment that returns this discussion to the straddled line of onsite and OWI; idea maps can be created easily online using a variety of tools, for many software programs and Web-based interfaces now include drawing software that afford idea mapping. Some software programs are especially made for creating visuals and charts of this sort, but simple drawing functions in Microsoft Word work as well, are fairly ubiquitous and accessible (although it must be made clear that not all students use Microsoft Word, and those who do their composing on a mobile device, as described in Chapter 16, will not find it easy to accomplish this kind of technology-enhanced visualization work for educational purposes).

A second type of visual suited to OWI is an annotated writing sample. An annotated writing sample is a document that includes callouts (often in color) with explanations or comments about effective or ineffective features of writing. Annotated writing samples often are found in textbooks; when included in an OWC with real comments from real instructors, annotated samples are excellent ways to provide personalized expectations about writing for students in a given class. Such annotations, however, might not be fully accessible to screen readers and may be unavailable when documents are saved to rich text or other than Microsoft Word formats.

Audio

Sound is an under-used medium in OWI that could be integrated easily and more fully. Sound appeals to a second sense in addition to the heavily used eyesight sense that both text and visuals engage. When more senses are added, it is possible that students will learn differently. Some will find sound to be an appealing and inclusive medium for learning. Therefore, OWI teachers should learn how and when to use sound in their OWCs. Two simple examples of engaging audio whether live or recorded are (1) using the phone and (2) integrating voice messages and/or podcasts to students.

Regarding phone use, I often remind instructors in training sessions that when a writing class is taught online, there is no reason that instructors and students cannot use the phone to communicate. In fact, adding a new medium diversifies communication and can benefit the interaction, while helping students who experience the OWC as distancing to feel more connected (Hewett, 2010, 2015b; Warnock, 2009). Additionally, all instructors and students already know how to use the phone, and it typically is accessible to all. Instructors might set up phone office hours and provide students with a phone number that students can call. Phone office hours provide students the clear benefit of knowing they can contact their instructor at noted times with any questions. It provides assurance that instructors will “be there” to help answer any questions. In-person office visits also are excellent for fully online students who are resident students or for those who are in hybrid OWCs.

Aside from using the phone, other audio methods include voice messages that can be posted asynchronously. Various digital recording devices and software enable voice recording and saving to a file. Sometimes, the software is integrated in an LMS. When the technology also translates voice into text, students can receive a visual text message with their instructor’s voice included, increasing accessibility. If provided as part of an LMS, students also can use the technology to communicate with other students, thus skipping the text-heavy need to write for that particular interaction. Podcasts are another audio tool that easily can be implemented in OWCs. Podcasts are audio recordings that are saved, archived, and made accessible via the Web. An effective illustration is the Grammar Girl website by Mignon Fogherty (2009) in which she creates several three-minute podcasts on topics of grammar, punctuation, and mechanics. Each podcast is accompanied by a text script, so listeners can read as they listen. Podcasts could be used by instructors in a similar way, such as by providing thoughts on an assignment or other class topic; instructors could provide commentary with script. In fact, audio messages have been used in conjunction with writing commentary, as well as to accompany presentations or texts. In sum, audio adds an element of personalization to the OWC in ways that are relatively simple and easy to implement.

Video

Audio/video, called simply video here, offers a multimedia option for OWCs that can combine visual, audio, and text productively. It addresses both the senses of sight and sound. With the evolution of common video and streaming technologies often used on the Internet and with social media, video has become a mainstay technology for the Web. As well, video has taken a prominent place in online learning. Many courses that experiment with a “flipped” instructional model include video lectures by instructors enabling more active work time in the class itself; hybrid OWCs can make good use of this model, for example. Video offers many affordances for teaching online writing. In this section, I address three possibilities for which OWI teachers might be trained: (1) asynchronous instructor videos, (2) synchronous video chats with students, and (3) video animations on writing topics (including screen casts).

Asynchronously provided instructor videos are useful tools for sharing course content or simple announcements about the course. Videos offer students a more personal connection with the instructor in that students can hear and see the instructor. Instructors can use simple, often free tools for video announcements. Short videos can be archived and then uploaded as Web links that can be attached to an online course and may even be reused in future OWCs. Instructors also can videotape lectures, although lectures are not a frequent instructional method in most writing courses. Some software affords the combination of visual writing examples or PowerPoint slides, instructor voice, and a picture if desired. Video also offers a promising method for instructors to return feedback to students about their writing. As Elizabeth Vincelette (2013) and Jeff Sommers (2012, 2013) among others have described, instructors can use video capture technology to comment on student papers. Video-capture enables instructors to make use of text, audio, and video to share comments, questions, reader response, and suggestions for revision for students to consider. This multimedia format is helpful to students in providing a diversity of communication that they can replay and integrate at their own speed.

Synchronous video chats are another tool instructors can use in OWCs. Synchronous video using easily accessed and common software can afford the opportunity for instructors to talk with students about their work. Synchronous video chats create opportunities for real-time, one-to-one student conferences; instructors can create a sign-up list and meet with the students at their assigned times. As well, synchronous video chats can be used to foster large or small class discussions. Large-class synchronous discussions might involve an instructor who mediates the discussion and reviews course material and/or readings. In the background, simultaneous written chats enable students present to fuel the large-class discussion. The instructor may field questions by reviewing student contributions to the chat. Synchronous meetings of this sort resemble a Webinar format.

Training is needed, however, because facilitating this kind of discussion can be an overwhelming experience, as OWI teachers must rely on their video and audio while reading simultaneous responses from a variety of students. There also is the issue of technology access and reliability, as synchronous sessions with large groups may experience technical difficulties while supporting multimodal elements such as video, audio, and text simultaneously for 20 people. A variation of synchronous discussions is to have small-group synchronous sessions with the instructor, which can make the interactions more manageable because smaller discussions tend to foster a more close-knit, personal sense of community. The instructor might schedule in advance certain times that students can meet with the instructor to discuss course material. Ideally, an instructor would share presentation slides or other material to the small group and field any questions. In a smaller synchronous discussion, students have the opportunity to each ask questions.

Finally, OWI teachers benefit from knowing about how animated videos can be used to supplement an OWC. Because OWCs often involve the use of various tools, instructors could create screen casts that illustrate different tools. A screen cast might be made to illustrate activities such as peer review (e.g., how to use the “comments” function of Microsoft Word); or a screen cast might be used to illustrate the features of the OWC’s Web interface. In addition to screen casts, videos on writing topics might be used. Projects like WRIT VID (2013) used animations to illustrate aspects of writing activities; likewise, many writing programs across the country are including videos with interviews of student and faculty writers. All of these videos can add supplemental material for the writing course.

Training on Modalities and Media

Training workshops offer instructors the important opportunity to investigate different modalities and media, with the goal of becoming more comfortable in the OWC environment. As well, gaining experience with different modalities and media will help instructors better associate with students who also must immerse themselves in the same space. One effective training exercise that engages the training principles of investigation, immersion, association, and reflection involves online peer review among teacher trainees. This activity must be conducted in an online environment, preferably the one teachers will use for the OWC. Teacher trainees should be grouped in pairs. Using the small group venue of the LMS, provide a peer review prompt in which you ask each pair to exchange documents and conduct peer review using a different modality and media. (A document that works well for exchange is the teaching philosophy statement created for the migration training activity shown in this chapter; however, any document could be used.) Assign each pair a different modality and media for their peer review, such as text-only, audio-only, video-only, or multimodal. This activity may require setting up an assignment or discussion prompt to enable their participation as students (rather than as teachers) in the training OWC.

The key to this assignment is not the actual peer review critique but an eventual consideration of the modality and media used. While the textual modality is essential and important for OWI, OWCs easily can make use of multiple modalities of communication and representation such as visual, voice, and video. Using these media from the student position enables immersion into the technology and a pedagogical strategy that can lead to more introspective reflection about one’s OWI activities, purposes, and perceived optimal outcomes. It also provides an opportunity for investigating not only different media but also other teacher trainees’ experiences of them.

Training Activity

In pairs, engage in online peer review using the teaching philosophy statements from earlier in the training or another suitable text. Each pair should conduct the online peer review using different modalities and media. Exchange your texts and, using the modality and media you’ve selected, engage in discussion with your peer by articulating any questions, comments, or suggestions about his or her text. Complete this peer review exercise within three days. Prior to the online peer review, you may find it useful to exchange contact information with your peer review partner(s) to set up a plan for technology and timing; this is the kind of engagement that students in the OWC also need to do, making it useful to learn firsthand the challenges of online interactions for assignment completion purposes.

- Pair 1: Text-only peer review (asynchronous)

- Pair 2: Audio-only peer review (asynchronous using voice email or other digital recording technology)

- Pair 3: Audio-only peer review (synchronous using phone)

- Pair 4: Video-only peer review (synchronous using online audio and video technology)

- Pair 5: Multimodal (asynchronous using a screen capture technology—that is, an uploaded document with comments, and voice annotation)

- Pair 6: Multimodal (synchronous using online voice technology and an uploaded document with written comments)

When you have completed the online peer review, engage with the entire training group in an online, text-based discussion about the different peer review modalities and media.

- What did each pair like and dislike about their modality and medium of peer review?

- What were the affordances and what were the constraints of their modality and medium?

- What was the rhetorical effect of each variation of peer review?

- What preparation was needed to set up the peer review?

- How might instructors facilitate such activities for students?

Morale