4.4: Invasion, Occupation, Imperialism and Hegemony

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 143299

- Melissa Leal & Tamara Cheshire

Genocide in the US - Colonialism Beyond Columbus

We survive war and conquest; we survive colonialism, acculturation, assimilation; we survive beatings, rape, starvation, mutilation, sterilization, abandonment, neglect, death of our children, our loved ones, destruction of our land, our homes, our past and our future. We survive, and we do more than just survive; we bond, we care, we fight, we teach, we nurse, we bear, we feed, we earn, we laugh, we love, we hang in there no matter what.

-Paula Gunn-Allen, 1992

As explained earlier in this chapter, genocide occurred in the United States. Colonialism itself is an act of genocide and needs to be recognized as such, but it is more complicated when you add Imperialism on top of Manifest Destiny and the Doctrine of Discovery.

Imperialism

Imperialism is an exploitative relationship between the United States and Tribes. The clearest example of imperialism in US history is the treatment of Native people. Treaties between the US government and Native nations recognized tribes as sovereign. The creation of the reservation system and the acquisition of reservation land in violation of treaties are textbook examples of imperialism and colonialism. The federal government created policies designed to promote either assimilation or extermination. Native lands were taken through conquest and incorporated into US territories, while Native Americans themselves were forced onto reservations and initially denied citizenship.

Sidebar - Timeline Native History in the U.S. from 1778 - 1885

- 1778 - First Treaty between the United States and the Leni Lenape or Delaware

- 1789 - The United States Constitution becomes effective. Congress has the power to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations and with Indian Tribes. The Constitution also provides that "the laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance of; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land”, thus superseding any other laws.

- 1790 - Congress passes the first Indian Trade and Intercourse Act which was modified in 1834. The Act prohibits conveyances of an Indian tribe's interests in land unless the conveyance is negotiated in the presence of a federal commissioner and ratified by Congress.

- 1831- Federal trust doctrine first described by the Supreme Court. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, and in the 1832 decision of Worcester v. Georgia, Chief Justice John C. Marshall articulated the roots of the federal trust doctrine and affirmed that Indian affairs was the province of federal rather than state regulation. In Cherokee Nation, an original action in the Supreme Court, the Tribe sought to enjoin Georgia from taking tribal land and imposing burdensome regulations on the Tribe. Chief Justice Marshall termed tribes "domestic dependent nations," with the federal/tribal relationship resembling "that of a ward to his guardian." The Court, ultimately, held that it lacked jurisdiction to hear an original action brought by a tribe against a state.

- 1832 - the Court revisited Georgia's attempt to control the Tribe in Worcester v. Georgia. Worcester, a minister and federal postmaster, and another non-Indian challenged their conviction in the Georgia courts for unlawfully residing on the Cherokee Reservation without a state license. The Court invalidated the state law and confirmed the Nation's sovereign rights under various treaties, including the right of self-governance and the right to occupy its own territory to the exclusion of the citizens of Georgia and of Georgia laws. According to Chief Justice Marshall, the "Cherokee nation . . . is a distinct community, occupying its own territory, . . . in which the laws of Georgia can have no force . . . ." The Court described Georgia's attempts to regulate the Cherokee as "interfere[ing] forcibly with the relations established between the United States and the Cherokee nation, the regulation of which, according to settled principles of our constitution, are committed exclusively to the government of the union."

- 1838 - Jackson’s Forced removal of the Cherokees begins. The election of Andrew Jackson in 1828 led to a change in the previous policy of seeking voluntary removal by eastern Indian tribes to western lands. In 1838, Jackson ordered the Army to begin forced removal of the Cherokees. The forced migration became known as the "Trail of Tears." Several other east coast tribes were also impacted and forcefully removed from their homelands.

- 1849 - Responsibility for Indian affairs transferred to the Department of Interior. The authority over Indian affairs was transferred from the War Department to the Department of the Interior pursuant to a statute that created the Interior Department. This change, however, did not precipitate a shift in federal policy, which continued to emphasize removal from eastern states. And despite the transfer, Congress continued to debate for a number of years whether the War Department should regain authority over Indian affairs.

- 1854 - First allotment of Indian tribal lands. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, George Manypenny, advocated reducing the size of reservations in combination with allotting portions of the reservation in severalty to individual Indians. In Manypenny's view providing Indians with private real property would help to establish "habits of industry and thrift as will enable them to sustain themselves."

- 1871 - An end to treaty making with Tribes. In 1871, Congress enacted an appropriations Act that included a rider stating "[t]hat hereafter no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty" This was because the House of Representatives was jealous of the power the Senate had in enacting treaties with tribes.

- 1885 - Major Crimes Act enacted. In 1883, the Supreme Court in Ex parte Crow Dog, 109 U.S. 556, overturned the conviction of Crow Dog for the murder of Spotted Tail, both members of the Brule Band of Sioux. The General Crimes Act, which at the time provided the basis for criminal law in Indian country, excluded "crimes committed by one Indian against the person or property of another." Such acts generally were dealt with under tribal law, rather than through federal prosecution. Crow Dog's prosecution took place on the theory that an 1868 Treaty with the Sioux had implicitly repealed the Indian exception to the General Crimes Act. The Supreme Court reversed Crow Dog's conviction, ruling that "[t]o justify such a departure, in such a case, requires a clear expression of the intention of Congress, and that we have not been able to find." In the wake of Ex parte Crow Dog, Congress enacted the Major Crimes Act in 1885. As enacted, the legislation provided that seven offenses, including murder and manslaughter, that, if committed against "another Indian or other person" within a territory or on an Indian reservation, constituted crimes under federal law. The Major Crimes Act in effect repealed the Indian exception to the General Crimes Act for certain crimes. The Major Crimes Act, as amended, is codified at 18 U.S.C. section 1153.

The Doctrine of Discovery and Manifest Destiny

According to the Upstander Project (2023), the Doctrine of Discovery established a spiritual, political, and legal justification for colonization and the seizure of land not inhabited by Christians. Foundational elements of the doctrine can be found in a series of papal decrees, beginning in the 1100's, which included expressions of territorial sovereignty for Christian monarchs supported by the Catholic Church. Two papal decrees that stood out include:

- "Romanus Pontifex" in 1455, granting the Portuguese a monopoly of trade with Africa and authorizing the enslavement of local people;

- “Inter Caetera” in 1493 to justify Christian European explorers’ claims on land and waterways they allegedly discovered, and promote Christian domination and superiority, and has been applied in Africa, Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and the Americas.

If an invader proclaims to have “discovered” the land in the name of a Christian European monarch, reports his “discovery” to the European rulers and returns to occupy the land, it is now his, even if someone else was there first. Furthermore, the “discoverer” can label the previous occupant’s way of living on the land as "inadequate" according to European standards, which justifies their claim to the land. This ideology supported the dehumanization of Native people, their dispossession, murder, and forced assimilation. The doctrine supported white supremacy as white European settlers claimed they were “instruments of divine design” and possessed cultural superiority.

In an 1823 Supreme Court case, Johnson v. M'Intosh, the Doctrine of Discovery became part of U.S. federal law and was used to dispossess Native peoples of their land. In a unanimous decision, Chief Justice John Marshall writes, “that the principle of discovery gave European nations an absolute right to New World lands” and Native peoples certain rights of occupancy (Johnson & Graham’s Lessee V. McIntosh, 21 U.S. 543, 1823).

The Doctrine of Discovery was the inspiration for Manifest Destiny, which justified American expansion westward by propagating the belief that the U.S. was destined to control all land from the Atlantic to the Pacific and beyond.

.jpeg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=550&height=409)

Manifest Destiny, coined in 1845 by newspaper editor John O’Sullivan, is the idea that white, Christian Americans were divinely ordained to "settle" (invade and steal) North America. This included a belief in the inherent superiority of white Americans as well as the conviction that they were destined by the Christian God to “conquer” the people and territories of North America. The ideology of Manifest Destiny was used to justify extreme measures to murder and decimate Native populations in order to “free” the land from its inhabitants, including forced removal and violent extermination. Proponents of Manifest Destiny advocated for and pursued a policy of removal. The ideology of Manifest Destiny inspired a variety of measures designed to commit genocide through removal or destruction the Native population that already inhabited North America.

Sidebar - Timeline Native History in the U.S. from 1921 - 1948

- 1921 - Snyder Act encourages spending for tribal needs. The Snyder Act authorized appropriations "for the benefit, care, and assistance of Indians throughout the United States." This legislation facilitated the passage of regular Indian appropriation bills to fund activities by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

- 1924 - Indian Citizenship Act enacted, The Citizenship Act of 1924 granted American citizenship to "all non-citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States." Indians would not have to go through a naturalization process.

- 1928 - Merriam Report published. The "allotment" period (beginning in 1887) created numerous health and welfare problems, which were detailed in this multi-year study undertaken by the Brookings Institute. The Report documented extensive poverty, disease, poor educational opportunity, and massive dislocation of Indians from their homelands. It recommended numerous changes, including the creation of a commission to hear Indian claims. The Report was a precursor to significant changes in federal policy.

- 1934 - Indian Reorganization Act (IRA). In 1934, Congress enacted the IRA to encourage tribes to revitalize their self-government, to take control of their "business and economic affairs," and to assure a solid territorial base by putting a halt to the loss of tribal lands through allotment. This sweeping legislation manifested a sharp change of direction in federal policy toward tribal sovereignty, replacing the assimilationist policy that had been in place since the General Allotment Act of 1887. The IRA prohibited any further allotment of reservation lands, extended indefinitely the periods of trust or restrictions on alienation of Indian lands, provided a mechanism for the acquisition of trust land for tribes, and prohibited any transfer of Indian lands (other than to the tribe or by inheritance) except exchanges authorized by the Secretary as "beneficial for or compatible with the proper consolidation of Indian lands and for the benefit of cooperative organizations." The overriding purpose of the IRA, however, was broader than remedying the negative effects of the General Allotment Act. As the Supreme Court has said, Congress sought to "establish machinery whereby Indian tribes would be able to assume a greater degree of self-government, both politically and economically." Congress thus authorized Indian tribes to adopt their own constitutions and bylaws and to incorporate. Congress also authorized the Secretary to take specified steps to improve the economic and social condition of Indians, including: adopting regulations for forestry and livestock grazing on Indian units, assisting financially in the creation of Indian-chartered corporations, making loans to Indian-chartered corporations out of a designated revolving fund "for the purpose of promoting the economic development" of the Tribes, paying tuition and other expenses for Indian students at vocational schools, and giving preference to Indians for employment in positions relating to Indian affairs. Of particular significance to the current work of the Section, Section 5 of the IRA authorizes the Secretary of the Interior "in his discretion," to "acquire. . .any interest in lands. . . within or without existing reservations, . . . for the purpose of providing land for Indians." The acquired lands "shall be taken in the name of the United States in trust for the Indian tribe or individual Indian." Pursuant to authority expressly delegated to the Secretary to prescribe regulations "carrying into effect the various provisions of any act relating to Indian affairs," the Secretary has issued regulations governing the implementation of his authority under Section 5 to take land into trust.

- 1943 - Tribal leaders create the National Congress of American Indians. The group sought to promote tribal interests at a national level.

- 1946 - Indian Claims Commission established. In 1946, Congress enacted the Indian Claims Commission Act (ICCA), which created the Indian Claims Commission (ICC), establishing a novel mechanism for Indian tribes to bring past claims against the United States. The cognizable claims under the ICCA included "claims in law or equity arising under the Constitution, laws, treaties of the United States, and Executive orders of the President," as well as claims for lack of "fair and honorable dealings that are not recognized by any existing rule of law or equity." Moreover, neither laches nor statute of limitations constitute permissible defenses to claims brought under the ICCA. Claims that had arisen prior to enactment of the statute were to be filed by 1951. Monetary compensation was the sole remedy available to the ICC. The Commission concluded its work in 1978 and transferred its remaining cases to the Court of Claims.

- 1948 - "Indian Country" defined. In 1948, Congress codified existing federal common law regarding what constitutes "Indian county" for purposes of federal criminal jurisdiction. The Supreme Court subsequently has applied the Indian country definition to determine the scope of tribal jurisdiction.

Removal, Reservations/Rancherias and Relocation

Often known as the 3R’s, removal, reservations/rancherias, and relocation greatly affected Native people both individually and collectively. Tribal systems rely on community and the collective ability of our people to work together within a familiar environment to survive. Once we are moved and relocated, we are no longer in a familiar place with family or community. We are forced to try to survive on our own without any help. What happens to our traditions and what are the ramifications to our families, our tribes?

Removal

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson (also known by his political platform as “the Indian killer”) signed the Indian Removal Act, which empowered the federal government to take Native-held land east of Mississippi and forcibly remove and relocate Native people from their homes in Georgia, Alabama, North Carolina, Florida, and Tennessee to “Indian territory”, or what is now Oklahoma. Tribes affected were the Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw and Seminole. From the southeast alone, the federal government moved roughly 60,000 people to eastern Oklahoma. This atrocity known as the Trail of Tears, which occurred up until 1907 resulted in tens of thousands of Native Americans dying or being murdered after being forcefully removed from their homes in error. The “Trail of Tears” is well known but there was not just one “Trail of Tears”; there were many instances where the federal government used their military to forcibly remove and relocate tribes. For example, in California in the 1860’s, the Concow Maidu were forcibly moved to Round Valley.

Known as the Nome Cult Trail or the Conkow Trail of Tears, which began on August 28, 1863; on that day, the Conkow Maidu people were rounded up by armed soldiers and began a grueling march from Chico to Round Valley. Of the 461 Conkow Maidu who began the journey, only 277 remained by the time they reached Round Valley. One hundred and fifty who were too exhausted, sick or malnourished to continue the journey had been left behind five days into the journey with only enough food to last them for a month. Others died of sickness, exhaustion, starvation, or thirst, while two managed to escape en route. Dorothy Hill writes in "The Indians of Chico Rancheria:" "Indian versions of the cruel hardships that their ancestors encountered on the drive to Round Valley are more explicit than the government accounts" (Hill, 1978).

According to Beth Stebbins’ book, The Noyo: “The problems that had beset the coastal reservation were carried over to the Round Valley reservation” (Stebbins, 1986) a number of first-person accounts of conditions on the Nome Cult reservation described hard-working Native Americans who labored on the farm and yet had not the means to obtain clothing, nor had they received clothing allotments in two years. There were no schools for the children, a dire scarcity of supplies, and “no substantial buildings erected for the Indians to live in,” according to Condition of the Indian Tribes: Report of the Joint Special Committee (1865):

Life on Nome Cult Farm was difficult in other respects as well. Not only did the original inhabitants of Round Valley, the Yuki, now have to confine their lives to only a small portion of their own ancestral land — Nome Cult Farm — they also had to live side by side with strangers from a number of other Native American tribes. Some of the tribes were enemies of the Yuki, and none had a common language (KCET, 2018).

Ethnic cleansing has been defined as the attempt to get rid of (through deportation, displacement or even mass killing) members of an ethnic group. Ethnic cleansing is also the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, often with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Removal policies were acts of ethnic cleansing, and meant to take land from Native American tribes and place it in the hands of white invaders.

The ideology of Manifest Destiny was also used to justify extreme measures to murder and decimate Native populations in order to “free” the land from its inhabitants, including forced removal and violent extermination. Proponents of Manifest Destiny led by the US government advocated for and pursued a policy of Indian Removal. The ideology of Manifest Destiny inspired a variety of measures designed to commit genocide through removal or destruction of Native people reinforcing settler colonialism, racist nativism and white supremacy.

Reservations/Rancherias

Reservations were one mechanism by which the federal government thought that they would be able to deal with “the Indian problem.” A federal Indian reservation is an area of land reserved for a tribe or tribes under treaty or other agreement with the United States, executive order, federal statute or administrative action as permanent tribal homelands, and where the federal government holds title to the land in trust on behalf of the tribe. Journalist Simon Moya-Smith (Lakota) writes “Indian reservations were first established as prison camps. The U.S. gave each prison camp a number. The Pine Ridge prison camp, for example, is prison camp 334. Then, the U.S. documented each Native by assigning them a number, too. That's why, today, we have enrollment numbers” (Moya-Smith, 2018). In California, most of the “reservations” are actually called rancherias. Rancherias were formed as land set aside for homeless Indians.

Approximately 56.2 million acres are held in trust by the United States federal government for various Indian tribes and individuals. There are approximately 326 Indian land areas in the U.S. administered as federal Indian reservations (i.e., reservations, pueblos, rancherias, missions, villages, communities, etc.).

The largest reservation is the 16 million-acre Navajo Nation Reservation located in Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. One of the smallest is a 6 mile rectangular parcel in Oregon where the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Confederated Tribe’s Council Office is located. Many of the smaller reservations are less than 5 miles long or wide. Native landholdings have decreased over the years (156 million acres in 1881 to 50 million in 1934) (Dunbar Ortiz, 2014, p. 11-12).

The fact that Native Americans, once confined to reservations and rancherias, did not have the resources to take care of themselves, tied into this stereotype and false imagery. Blaming Native people for their own impoverished conditions when they had nothing to do with it, helped to ingrain the “lazy Indian” image into the American psyche.

Relocation

Congress passed a resolution (House Resolution No. 108, 83rd Congress, August 1, 1953) beginning a federal policy of termination, through which American Indian tribes would be disbanded and their land sold. A companion policy of “relocation” moved Indians off reservations and into urban areas. Operation Relocation of 1952, which moved reservation Natives to urban areas, promised transportation, training, work and housing. This happened in major cities across the nation, including Chicago, Dallas-Fort Worth, Denver, Detroit, Los Angeles, Oakland, San Francisco, Portland, etc. Relocation was successful in moving a majority of Natives to urban locations. By 1980, 50% of Native people lived in urban areas. The goal was to assimilate Natives by encouraging them to marry non-Natives. But this plan somewhat backfired. Although intermarriage occurred, many urban Indians did not melt into urban White America. Instead, they looked for ways to remain Native. Intertribal pow-wows were a way to retain connections and traditions. Urban Indians created ways to remain Native and never surrendered their identities.

Dawes Act

Sidebar - Laws and Acts 1887

- 1887 - General Allotment Act - The General Allotment or Dawes Act established the allotment of tribal land in severalty to individual Indians and the abolition of the tribal system as the major tenets of federal Indian policy. The Act authorized the President to survey reservations and allot lands to individual Indians for use as agricultural or grazing lands. Title to these lands was to continue to be held in trust for 25 years, at which point the land would be patented to the individual in fee. The program, as it developed, led to a considerable amount of land losing its trust protection and being sold to non-Indians. As a result, by 1900, Indians retained approximately one-half of the land that they had held in 1881. Congress did not revisit Indian policy or the allotment approach in a comprehensive manner until 1934.

The 1887 Dawes Allotment Act was a way in which the federal government could obtain reservation land, established through treaties. Between 1870-1900, federal Indian policy changed from treaty making, removal, establishing reservations and warfare to a new policy meant to break up reservations and tribal lands. The Dawes Act, named after Senator Henry Dawes of Massachusetts, authorized the President to break up reservation land into small allotments parceled out to individual Native Americans, encouraging farming. The key term here is "individual":

To each head of a family, one-quarter of a section; To each single person over eighteen years of age, one-eighth of a section; To each orphan child under eighteen years of age, one-eighth of a section; and To each other single person under eighteen years now living, or who may be born prior to the date of the order of the President directing an allotment of the lands embraced in any reservation, one-sixteenth of a section (Dawes Act, 1887).

Although this act did not initially apply to all tribes because several were exempt, Dawes was another effort to assimilate Native people into American society, break treaty rights and obligations of the federal government and ultimately economically benefit the federal government once more through the stealing and selling of Native land. Through this effort of assimilation, the federal government did not have to follow their treaty obligations to provide for tribes in exchange for Native land, because they could just take it.

The Dawes Act abolished tribal governments and recognized state and federal laws as superseding tribal sovereignty. Individual Indians were listed on rolls in order for the Department of the Interior to determine eligibility for land distribution. Further excuses were used to promote the act including listing individual land ownership as a way to protect American Indian property rights. Removing land from tribal possession meant the disruption and obstruction of tribal governance, sovereignty, traditions and way of life. To make matters worse, land allotted to individuals was usually unsuitable for farming, which was required in order to maintain individual land ownership. In addition, individuals could not afford all the necessary resources like tools, animals, seeds and supplies necessary to begin, let alone maintain a farm. Tribes were left unpaid or underpaid for the land allotments which often were too small to farm. Native people often were not able to afford the taxes on the property, so it began to be confiscated by the state; which was an issue for the federal government. Allotments were also outright sold to non-Native individuals, resulting in extensive loss of tribal lands. The Dawes Act (1887) document can be found at the National Archives website.

Prior to the Dawes Act, tribes relied on treaty rights to protect their land claims, especially when it came to the federal government attempting to take more and more tribal land. Treaty rights protected original agreements between tribes and the federal government. After the Dawes Allotment Act of 1887 and the Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock (1903) Supreme Court’s decision; Congress could apply any Act to Native Americans regardless of prior treaty rights. This court ruling allowed for the federal government to have superior power over Indian tribes.

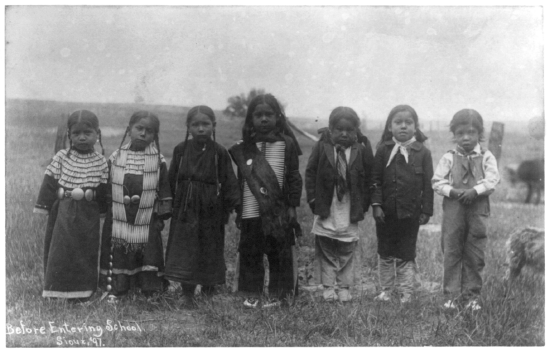

Assimilation, Boarding Schools and Adoption

Over 100,000 Native American children were forced to attend boarding schools. The main primary role of this education for Indian girls was to inculcate patriarchal norms and desires into Native culture, so that women would lose their places of leadership in Native communities (Smith, 2004, p. 89-90).

Another federal government assimilation initiative and prime example of cultural imperialism that was allegedly done for the "benefit" of Native people was the creation of boarding schools. Richard Henry Pratt founded Carlisle Indian School at an abandoned military barrack in Carlise, Pennsylvania. Pratt believed that Native people and cultures were inferior and proposed that the cultures be eradicated through forced assimilation of Native children, in order to “kill the Indian to save the man.” Pratt and others recognized that it would be much easier to assimilate children rather than adults, and easier still if the government could separate children from their families and tribes.

Whether they attended Haskell Industrial Training School in Lawrence, Kansas, Sherman Institute in California, Chemawa Indian School in Oregon, or anyone of the 367 schools in United States, Native children were forbidden from practicing their ceremonies and traditions, and would be punished if they spoke about their families or spoke their tribal language. Violence against children was sanctioned through corporal punishment. Girls were taught to be maids and domestic servants for white households and boys were taught farming and industrial labor. If parents resisted, their children would be taken by force.

For a comprehensive list of Native American Boarding schools in the United States please see the PDF created by the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

Adoption

The boarding schools closed because they were no longer affordable for the federal government to support. The Bureau of Indian Affairs worked with the states and turned to the adoption of Native children to white parents and families. They utilized the state’s family court systems and child protective services to institute systemic racism in policies and procedures in order to kidnap Native children from their families. It was an extension of what the Bureau of Indian Affairs had done previously with the boarding schools, but this time it was sanctioned by the state, who received funds from the federal government as incentive.

Indian Child Welfare Act

Sidebar - Laws and Acts 1978

- 1978 - Indian Child Welfare Act - Congress passed ICWA in response to the alarmingly high rate of Native children being separated from their parents, extended families, and tribal communities.

The 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) was established in response to previous assimilationist policies by the U.S. federal government. Beginning with boarding schools and then adoptions of Native children to non-Native parents and moving to high numbers of Indian children forcibly removed from their families by public and private agencies and placed in non-Native foster homes, the Indian Child Welfare Act was meant to keep Indian children with Indian families. The actual act can be found under the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 (25 USC §§ 1901-63) at the Tribe Court Clearinghouse.

ICWA itself provides preference of who can foster and adopt Native American children. Preference goes in the following order: first to Native family members, this includes extended family like grandparents, aunts, uncles, brothers, sisters, cousins, etc.; second, the tribe the child belongs to; third, any Native family, regardless of tribe. It is important to note that this law applies to states and state agencies, not to tribes. Although federally recognized tribes have the right to petition the state courts that Native children be placed in their care with Native foster parents on reservations, often state judges refuse this placement and elect to place Native children in local non-Native foster homes. We must ask why would judges choose to place Indian children in foster care with non-Indian parents/families? The answer to this question is financial gain. The more Native children placed in foster care, the more money the state receives for these children.

Termination

Sidebar - Laws and Acts 1952 - 1970

- 1952 - House of Representatives signs termination policy. The House of Representatives endorsed a resolution calling on a committee to propose legislation "designed to promote the earliest practicable termination of all federal supervision and control over Indians."

- 1953 - House Resolution on termination passes. Congress unanimously adopted House Concurrent Resolution 108 stating that it was "the policy of Congress, as rapidly as possible, to make the Indians within the territorial limits of the United States subject to the same laws and entitled to the same privileges and responsibilities as are applicable to other citizens of the United States, to end their status as wards of the United States, and to grant them all of the rights and prerogatives pertaining to American citizenship." Among other things, it specifically called for the termination of the Menominee Tribe of Wisconsin. Subsequently, the Tribe was informed that unless it agreed to termination it would not receive funds that had previously been awarded by the Indian Claims Commission. Numerous other tribes also were terminated by specific statutes following the approval of the Resolution.

- 1954 - Congress terminates a group of tribes. In 1954, Congress enacted legislation terminating the Southern Paiute of Utah, the Alabama and Coushatta Indians of Texas, the Klamath of Oregon, the Menominee Tribe of Wisconsin, and other tribes and bands in Oregon. Congress terminated additional tribes over the next eight years.

- July of 1970 - President Richard Nixon formally ended the termination policies established in the 1950’s and announced a new policy of "self-determination without termination." The administration introduces 22 legislative proposals supporting Indian self-rule.

Termination occurred in 1953 when the U.S. Congress adopted an official policy of termination declaring that the goal was to, “as rapidly as possible make Indians within the territorial limits of the United States subject to the same laws and entitled to the same privileges and responsibilities as are applicable to other citizens of the United States” (House Concurrent Resolution 108). The real goal of termination was the theft of Native lands; and a companion policy was the “relocation” of Native people off reservations into urban areas. From 1953 to 1964, 109 tribes were terminated, and federal responsibility and jurisdiction were turned over to state governments. Approximately 2,500,000 acres of trust land was removed from protected status (sold to non-Natives) and 12,000 Native Americans lost tribal affiliation as well as resources guaranteed through treaty for all time.

State Recognition and State Law PL 280

Sidebar - Laws and Acts 1953 - 1976

- 1953 - Public Law 280 enacted. Congress enacted a statute that delegates to five states criminal and civil jurisdiction over Indian lands within their boundaries.

- 1976 - Supreme Court limits reach of Public Law 280 - In Bryan v. Itasca County, the Supreme Court ruled that Public Law 280, which was enacted in 1953, does not provide for state regulatory power over Indian lands.

Public Law 280 which was passed in 1953 is a federal law of the United States establishing a method whereby States may assume criminal jurisdiction over reservation Indians and to allow civil litigation that had come under tribal or federal court jurisdiction to be handled by state courts. State governments and tribes disapproved of the law. Tribes disliked states having jurisdiction without tribal consent and state governments resented taking on jurisdiction for these additional areas without additional funding. With mutual dissent, additional amendments to Public Law 280 have been passed to require tribal consent in law enforcement and in some cases, the states have been able to return jurisdiction back to tribes and the federal government. However, the act mandated a transfer of federal law enforcement authority to state governments in six states. Mandatory PL-280 states are: Alaska (except the Metlakatla Indian Community), California, Minnesota (except the Red Lake Reservation), Nebraska, Oregon (except the Warm Springs Reservation), and Wisconsin.

Decolonization

Decolonization may be defined as the active resistance against colonial powers, and a shifting of power towards political, economic, educational, cultural, independence and power that originate from a colonized nation's own Indigenous culture. This process occurs politically and also applies to personal and societal, cultural, political, agricultural, and educational deconstruction of colonial oppression. Per Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang: “Decolonization doesn’t have a synonym”; it is not a substitute for ‘human rights’ or ‘social justice’, though undoubtedly, they are connected in various ways (Tuck & Yang, 2012). Decolonization demands an indigenous framework and a centering of Indigenous land, Indigenous sovereignty, and Indigenous ways of thinking (Tuck & Yang, 2012).

Decolonization refers to fighting back against the ongoing colonialism and colonial mentalities that permeate all institutions and systems of government. Decolonizing actions must begin in the mind, and that creative, consistent, decolonized thinking shapes and empowers the brain, which in turn provides a major prime for positive change. Undoing the effects of colonialism and working toward decolonization requires each of us to consciously consider to what degree we have been affected by not only the physical aspects of colonization, but also the psychological, mental, and spiritual aspects.

Stereotypes, Othering and Invisibility

Brian Baker discusses othering and the stereotypes of Native people in his chapter “Imaginary Indians: Invoking Invented Ideas in Popular and Public Culture” (Baker, et. al., 2011). Baker establishes that the purpose for his article is to provide an analysis related to imaginary Indians based on ideas invented by members of white American culture that functioned to set Indians apart from society as the “other.” Baker begins with a discussion of the relevance of being relegated to the status of “other” as it relates to public and popular culture. He argues that in order to understand the ideas of imaginary Indians, one must decolonize the mind.

Baker’s four interrelated dimensions of imaginary Indians include:

- Indians roaming the land

- Indians as children

- Wild and dancing Indians

- Indians as redskins and warriors (via mascots)

In Baker’s (2011) article, Native men are portrayed as violent, Native women as hyper-sexualized, and both are in need of care like children, from the "great white father," forcing a patriarchal, patronizing, treatment onto Native people. This false narrative and oppressive treatment dehumanizes Native people while at the same time supports westward expansion by the "brave pioneers" and reinforces settler colonialism.

The group that becomes the "other" in American political, economic and cultural institutions, experiences invisibility and visibility in their daily lives. The "other" is invisible because they are ignored and unnoticed while at other times the "other" is visible but only through stereotypes. In both situations, the ideas that are invented and invoked play a key role in how individuals within a group experience their lived status as the other, despite the fact that invented ideas are rooted in an imaginary world (Baker, 2011).

Stereotypes about Native people were created and used by Americans to rationalize and justify settler colonialism, manifest destiny, white supremacy, and ultimately racist nativism. These stereotypes continue to exist in American popular culture because of the desire to keep Native Americans within the category of the “other.” Understanding the powerful reality of colonialism and institutional racism, we must deconstruct and examine our basic ideas that we have been socialized into accepting uncritically.

Americans invented ideas about imaginary Indians as a way to explain and validate the effective ways in which they subjugated Native peoples who became Indians.

Indians roaming the land....

Invented stereotypes have become so effectively institutionalized within the framework of public culture that they have been ingrained into the American imagination. The imaginary Indian wandering aimlessly over the land was a powerful political philosophy central to Manifest Destiny in that it validated the idea that Indians did not “settle” on the land because they “roamed” over it; implying there was something wrong with them because they could and would not “settle” in the same way colonists did, therefore they had no “rights” to the land.

White American lawmakers and officials in the Bureau of Indian Affairs exploited “roam” and “wander” in reference to Indians in order to justify how the U.S. would deal with the so-called “Indian problem.” Eventually it became necessary to constrain the roaming Indians and limit their human existence on the landscape by drawing reservation boundaries around them in order to enclose and isolate them from American society. Once relegated to an inhumane existence on reservations where it was not possible to support their families, the roaming Indians no longer existed as obstacles to Americans who were provided with the opportunity to "settle" and bring "civilization" to the landscape.

Devaluing Indigenous ways of knowing and living within their environment while at the same time not having to “conquer” it, is a way to colonize and stereotype cultures who have lived and thrived here for hundreds of thousands of years. In so doing, minimizing Indigenous existence is another way of making an excuse for taking the land and killing the people, effectively sanctioning genocide.

Indians as children....

Throughout the 19th century, American political officials increasingly described Indians as children who needed to be cared for. In this way, they could create a parent-child relationship, not only controlling Native people but also their resources. Framed as “children,” Native people could not be trusted to take care of themselves or even be around others because they were not responsible, they were lazy and greedy, like children.

Federal policy, through various Acts, laws, Executive Orders and court rulings, created a guardian status for the federal government with inherent authority over the Indian as a ‘“ward” of the court. The American government created the idea of the “Great Father” who cared for the “red children” who, due to their “inherent cultural inferiority,” required constant American paternalistic guidance.

The fact that Native Americans, once confined to reservations, did not have the resources to take care of themselves, reinforced this stereotype and false imagery. Blaming Native people for their own impoverished conditions when they had nothing to do with it, helped to ingrain the “lazy Indian” image into the American psyche. Uncle Sam being the Great Father taking care of his “red children” whom he inherited when he came to this continent, is also a metaphor for why Uncle Sam doesn’t take very good care of his ‘red children’ and provides them with inferior food; because it is an excuse or punishment for them being lazy and non- productive like other ‘“hard working” white? Americans.

Wild and Dancing Indians....

Wild and dancing Indians have been a long standing stereotype that has been reinforced in adult and children's literature as well as children's movies like Peter Pan. If you have ever seen Disney’s Peter Pan, you will know about the “wild dancing Indians.” In addition, you may also be able to make the connection to the Hollywood “cowboy and Indian” movies where the stereotypes of the imaginary Indian prevails. These images regulate Indians to the status of “other” in American society and simply equates Indian with “deviant, uncontrollable behavior,” which is similar to the previous imagery of the Indian as the child. On the flip side, drinking and debauchery are often associated with adult Indians. This bleeds into the idea that the Native American male is a wild savage that can’t be trusted, especially around white women. In the example below, Frank Waln who is an award winning Sicangu Lakota Hip Hop artist and music producer from the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota uses the song "What makes the red man red" in Disney's Peter Pan as a base for his rap song to call out the pervasive stereotypes. Waln has is BA in Audio Arts and Acoustics from Columbia College in Chicago. Waln has three Native American Music Awards. He has written for various publications including Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, and Society and The Guardian. Frank Waln travels the world telling his story through performance and doing workshops focusing on self-empowerment and expression of truth.

Sidebar: Lyrics to "What makes the red man red" by Frank Waln

Watch this video and listen to this song by Frank Waln –What makes the red man red?

[Intro]

Personally, I should prefer to see the aborigines

And the Indians, too!

And the Indians, too!

This should be most enlightening

What makes the red man red?

Teach 'em all about red man

[Chorus]

What made the red man red?

What made the red man red?

What made the red man red?

What made the red man red?

Teach 'em all about red man (red man)

[Verse 1]

Your history books (lies)

Your holidays (lies)

Thanksgiving lies and Columbus Day

Tell me why I know more than the teacher

Tell me why I know more than the preacher

Tell me why you think the red man is red

Stained with the blood from the land you bled

Tell me why you think the red man is dead

With a fake headdress on your head

Tell me what you know about thousands of nations

Displaced and confined to concentration camps called reservations

We died for the birth of your nation

Hollywood portrays us wrong (like savages)

History books say we're gone (like savages)

Your god and church say we're wrong (savages)

We're from the Earth, it made us strong

[Chorus]

Many moons, red man fought paleface

What made the red man red?

What made the red man red?

What made the red man red?

What made the red man red?

Please, you want to stay here and grow up like, like savages?

[Verse 2]

Savages is as savage does

The white man came and ravaged us

Caused genocide, look in my eyes

And tell me who you think the savage was

Savages?

Savages?

Their great celebration continued into the night

[Bridge]

Manifest destiny arrested what's best for me

They kill my culture, America made a mess of me

You inherited everything we die for and all we get is a goddamn mascot

Manifest destiny arrested what's best for me

They kill my culture, America made a mess of me

You inherited everything we die for and all we get is a goddamn mascot

Redskin, red-redskins, redskins, redskin, those redskins

Many moons the red man fought paleface

Sometimes you win, sometimes we win

You made me red when you killed my people

Made me red when you bled my tribe

Made me red when you killed my people

(Like savages, like savages)

[Chorus: The Chief & Frank Waln]

The real true story of the red man

The real true story of the red man

No matter what is written or said

What made the red man red?

All the lies that you spread

What made the red man red?

All the blood that you bled

What made the red man red?

All the lies that you spread

What made the red man red?

You, you

[Outro]

Pale-face savages

Pale-face savages

Go out and catch a few Indians

Savages

Indians as Redskins and Warriors

During the timeframe when Americans imposed the most constraints over Native people preventing them from practicing their religions and speaking their languages, preventing them from asserting important dimensions of their indigenous identities, Americans became more fascinated with and began to “play Indian” in reference to their imaginary world relating to Indians. Some scholars say this is when the American psyche, riddled with guilt for the genocide they had committed, attempted to make amends by taking over complete control of Indigenous identity, glorifying the “fight til the end” when there were “no more” Native people, thereby rendering the Native people left, invisible.

Since the 1700’s non-Natives have literally collected and worn cultural artifacts to “play Indian” reflecting dominant cultural interpretations and ideas about Indians. “When the symbolic dimensions of Indian are invoked in reference to the material objects associated with the idea of Indian, the assumption is that one passes through racial and ethnic boundaries to become Indian” (Baker, 2011, p. 353). Thus the ability to play Indian by members of the dominant society in the context of popular culture is intimately tied to the invented ideas that reflect American racism towards Indians. In this imaginary world, all Indians are the same.

The imaginary Indian has also been invented as a mascot and team name in American sports and has been institutionalized in popular culture. Indians are conceptualized as “fierce heathen warriors” inherently prone to “being cold-blooded and cunning” in their ability to fight and kill. Indians have been set apart in popular culture with purposeful stereotypes and derogatory names like redskins, wahoos and wagonburners.

Mascots have been argued by non-Natives to be something that should “honor” Indians because of the qualities the mascot stands for; but this is based on the imaginary Indian, and not true histories and identities, ignoring Native American voices. The erasure of real Indians is the issue. The very concept and name "redskin" is directly connected to genocide. The team "redskin" comes from the bounties that were paid to settlers for bringing in the scalps/heads/bodies of dead Indians. Team owners and many Americans choose to ignore and hide behind ignorance in their refusal to acknowledge this fact.

It is extremely difficult to change ideas associated with the imaginary Indian because the reality is that those ideas have been effectively institutionalized within the frameworks of public culture and ingrained in the American psyche. Children today still act on the legacy of stereotypes created more than 400 years ago through a history of colonialism. Native people today are still being defined as the “other” through the use of stereotypes including the use of the “chief” or “redskin” as mascots. As long as the imaginary Indian continues to have an existence in American popular and public culture as a “redskin warrior,” Indians in America will continue to experience institutionalized racism due to their colonially imposed status as the “other” (Baker, 2011).