10.2: The Prison Industrial Complex

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 143345

- Ulysses Acevedo & Kay Fischer

Opening

When introducing the prison industrial complex (PIC) I often ask students what PIC means to them? Among many silent and contemplative faces there are students who share their thoughts: it’s caging people, school-to-prison pipeline, unfair sentencing, racial profiling, the bail system, etc. In a class, students can often paint an accurate picture with their words. Critical Resistance, a non-profit organization, defines the prison industrial complex as “a term used to describe the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems” (What is PIC? What is Abolition, Critical Resistance, Accessed September 16 2022).

Private Prisons

In her book Are Prisons Obsolete? Angela Y. Davis states that “the term ‘prison industrial complex’ was introduced by activists and scholars to contest prevailing beliefs that increased levels of crime were the root cause of mounting prison populations. Instead, they argued, prison construction and the attendant drive to fill these new structures with human bodies have been driven by ideologies of racism and the pursuit of profit” (Davis, 2003, p.84). Furthermore, private prisons have effectively influenced public policy in the chase for profits by utilizing lobbyists to pass laws further criminalizing Black Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC) communities.

Although there are legislative efforts to reverse private prisons in the U.S., especially in California, their impact on individuals, families, and communities are irreversible. The prison industrial complex and the privatization of prisons put the U.S. as the leader in the highest incarceration rates in the world. During the 1980s the rise of justifying harsher sentencing practices was perpetuated by elected officials and the media arguing “that this was the only way to make our communities safe from murderers, rapists, and robbers” (Davis, p. 91). Davis goes on to state that in the year 2001 there were 2,100,146 people incarcerated in the US but that only looking at population sizes erases the stories of those who are incarcerated (p. 92). “According to 2002 Bureau of Justice Statistics, African-Americans as a whole now represent the majority of county, state, and federal prisoners, with a total of 803,400 Black inmates—118, 600 more than the total number of white inmates. If we include Latinos, we must add another 283,000 bodies of color” (p. 94).

Private prisons function with public funding however work under their own systems in managing prisons and incarcerated people. How do private prisons make money? In answering this question we have to ask another question, how do hotels make money? Both private prisons and hotels share a similar business model whereas the more cells (rooms) and beds are occupied the more money the prison or hotel is making. An empty cell (room) is seen as a lost opportunity to make more profit. “In arrangements reminiscent of the convict lease system, federal, state, and county governments pay private companies a fee for each inmate, which means that private companies have a stake in retaining prisoners as long as possible, and in keeping their facilities filled” (Davis, 2003, p. 95). The business of private prisons is to keep their prisons full, more humans incarcerated ultimately equates to higher profit margins for the prison investors. Also, Davis utilizes the military industrial complex and the medical industrial complex as examples that are “driven by an unprecedented pursuit of profit, no matter what the human cost” (p. 91).

Furthermore, the trend of privatizing prisons is becoming the primary mode which became viable through corporations entering the prison economy and is “reminiscent of the historical efforts to create a profitable punishment industry based on the new supply of 'free' Black male laborers in the aftermath of the Civil War” (p. 93). After the Civil War, slave labor was no longer an option for planters and other emerging industries but the convict lease system, chain gangs, and debt peonage were used for cheap or free labor. One example of corporations doing business in prisons is selling the prisons and inmates products such as Dial Soap, Famous Amos Cookies, AT&T, and health providers (p. 99).

In the case of private prisons, the customers are non-incarcerated humans who expect society to deal with humans who have “broken the law” through punitive justice or incarceration. Non-incarcerated humans are the customers to private prisons because everyone between the working class to the upper class are paying the taxes to pay for the subsidies provided by the federal and state government to private prisons. The funding of prisons by non-incarcerated humans goes unnoticed and unchallenged most of the time. The free population is generally happy when they believe that "bad people" are in cages. For example, have you ever used the phrase deadline? An example of its usage- “the deadline for the assignment is by Friday at 5pm.” The phrase “deadline” is derived from prison lingo where a corrections officer can shoot and kill a prisoner for crossing over a physical line (or fence) around the perimeter of the prison, hence “deadline.” Prisons as a business use “public safety” to make non-incarcerated humans feel like they are getting their money's worth. Prisons make their customers content when they feel incarcerated people will not escape prisons (think Alcatraz Island).

In an article titled “Sweet deal, but for a few: Private prisons and immigrants,” by Kevin P. Soto (2014) includes a cycle chart titled “follow the money” to demonstrate how money and private prisons relate with one another. The “follow the money” cycle chart includes the following four themes as a fiscal flow to private prisons: incarcerated people, CEO’s getting paid, private prison lobbyist, and prison budgets and policies. This chart is an example of third theme for a business model framework, value capture which is “the fiscal flows and economic aspects of relations to main stakeholders, such as employees, suppliers, owners, and customers” (Soto, 2014).

Furthermore, the flow chart shows that for private prisons profits are central to the business model and not other factors such as justice or treating incarcerated people and their families with respect. In order to fine tune profitability for stakeholders and their CEO’s private prisons have influenced public policy to secure the perpetual criminalization of people in order to fill prison cells and secure profits. It is helpful to understand the influence of private prisons on public policy to be able to reverse the over-policing of poor and BIPOC communities.

It is important to note that there is currently a moral shift (locally and nationally) in the U.S. to undo the damage caused by the practice of private prisons incarcerating humans in the chase of profits. For example in 2019 California passed AB32 which would ban private prisons (including private immigration detention centers) contracts in California and would take effect on Jan. 1, 2020 (Castillo, 2021).

Prison Labor: From Slavery to Convict Leasing

The poster in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) by Melanie Cervantes calls attention to the Nationwide Prison Strike from Aug 21 - Sep 9, 2018, highlighting the exploitation of modern-day prison labor. Two prisoners are centered in the poster with a man holding a "Strike" flag. Angela Y. Davis explained that the penitentiary system was supposed to be about rehabilitation and providing convicts with time to reflect on the crimes they committed with “penitence.” This was viewed as progressive at the time it was developed (during the era of the American Revolution), compared to the former system of corporal or capital punishment, inherited from England. But, Davis pointed out, such a concept ignored the impact of an authoritarian regime. She wrote:

The ideologies governing slavery and those governing punishment were profoundly linked during the earliest period of U.S. history. While free people could be legally sentenced to punishment by hard labor, such a sentence would in no way change the conditions of existence already experienced by slaves (2003, p. 28).

Even Thomas Jefferson pointed out that penal labor made no difference in the condition of the slave. Citing the work of Adam Jay Hirsch, Davis summarizes how the daily routines of incarcerated people were controlled by their superiors, much like enslaved people. Both groups were also reduced to complete dependence on others for basic needs like food and shelter, were isolated from the general population, and forced to work for long hours with little to no compensation. Furthermore, Davis pointed out the similarities between prison rules and slave codes.

When slavery was abolished, new laws were passed in southern states rewriting slave codes to monitor the behavior of freed Black Americans. Black codes were applied to specific actions that were criminalized only if the person charged was Black, including vagrancy, absence from work, breach of work contract, owning firearms, or insulting gestures and acts. Davis wrote that there is a long U.S. history of race playing a “central role in constructing presumptions of criminality” (2003, p. 28). Furthermore, the Thirteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution abolished slavery “except as punishment for crime, whereof the party shall have been fully convicted” (U.S. Const. amend. XIII).

In fact, Davis argued that the post-slavery criminal justice system in the south was specifically developed in order to regulate the newly attained freedoms of former slaves. Historian Mary Ellen Crutin (2000) found that the prison population suddenly became overwhelmingly Black after slavery. Her research focused on the state of Alabama, where in the years before slavery was abolished, the prisoner population was 99% white. Despite this, Curtin pointed out that, “the popular perception that the South’s true criminals were its black slaves” and many white Southerners believed that Black Americans were “inherently criminal and, in particular, prone to larceny” (p. 29). So much so that there were even cases of when white people dressed up to appear “black” or blame crimes on a Black person.

Furthermore, Davis wrote that, “Black people became the prime targets of a developing convict lease system, referred to by many as a reincarnation of slavery” (2003, p. 29). This meant that not only were formerly enslaved people subject to racist laws that criminalized them, but if their alleged crime was coded as a “black crime,” their punishment would include forced labor, sometimes in a cruel fate at the same plantations that formerly “thrived on slave labor” (p. 29). To add insult to injury, the punishments inflicted on incarcerated Black Americans during the post-slavery era were the same ones used during slavery, including: whipping, lashes, and chains. Chain gangs and convict leasing was ultimately about controlling Black labor, and continued the legacy of slavery. Black prisoners were subject to constant supervision and under watch with the threat of the lash.

Davis found that many scholars researched how convict leasing was worse than slavery. Under slavery, the owners cared about the survival of individual slaves, who represented an economic investment. Competitively, prisoners were leased as groups under convict leasing and were literally worked to death without impacting the profitability. The work conditions were abysmal. For example, in the Mississippi plantations in Yazoo Delta in the late 1880s, prisoners were forced to sleep on the ground without blankets, often without clothes. They were punished with lashes for “slow hoeing” (ten lashes), “sorry planting” (five lashes), “being light with cotton” (five lashes). If people tried to escape and were caught, they would be whipped “till blood ran down their legs.” Others had metal spirals riveted to their feet. Many dropped from exhaustion, pneumonia, malaria, frostbite, consumption, sunstroke, dysentery, gunshot wounds, and “shackle poisoning” (which is the constant rubbing of chains and leg irons against bare flesh) (2003, pp. 32 - 33).

Lichtenstein argues that the convict lease system, along with Jim Crow laws, acted as the “central institution in the development of a racial state” (Davis, 2003, p. 34). Capitalists in the South used state resources to access a convict labor force, never having to rely on a waged labor force. Georgia railroads were in fact constructed with Black convict labor. Davis argues that this supported industrialization in the South, including coal and iron mining. She further states, “Black convict labor remains a hidden dimension of our history,” making connections to how today we may all take for granted the countless products made through prison labor, including college and university furniture (p. 35). More recently, there’s been press covering how the state of California has relied on incarcerated labor to fight wildfires, who are paid only a few dollars a day, while facing life-hazardous conditions. Also, according to a recent report on “Captive Labor,” incarcerated people were also on the front lines of pandemic responses, manufacturing hand sanitizer, masks, medical gowns and other personal protective equipment that they themselves were not allowed to use to protect themselves. Incarcerated labor also transported dead bodies, dug graves, and built coffins (ACLU and the University of Chicago Law School’s Global Human Rights Clinic, 2022).

To boot, corporations and the government benefit the most from incarcerated labor, ultimately giving clear incentives to incarcerate a larger prison population. Despite convict leasing ending, the “structures of exploitation” remained and are repeated today. The “Captive Labor” report argues that the key beneficiaries of such labor are federal, state, and local governments who offset budget shortfalls by exacting incarcerated labor to maintain the very institutions they are caged in (including preparing food, laundry, cleaning, etc.). State and local governments rely on incarcerated labor for public works projects like maintaining public roads, ditches, and so forth. In Florida, it’s estimated that the unpaid prisoner labor is valued at around $147.5 million over five years. There are also state-owned businesses that exploit incarcerated labor to produce certain goods and services. For example,

In fiscal year 2020, …California’s correctional industries program sold over $191 million in manufactured goods, services, and agricultural products produced by incarcerated workers in fiscal year 2020–21. In 2021, the value of goods, services, and commodities produced by the incarcerated workers employed in state prison industries programs nationwide…totaled over $2 billion (ACLU et al., 2022, p. 17).

Finally, Curtin (2000) argues that some newly emancipated Black Americans were made into criminals, being forced to steal in order to survive. Davis (2003) wrote, “It was the transformation of petty thievery into a felony that relegated substantial numbers of black people to the ‘involuntary servitude’ legalized by the Thirteenth Amendment” (p. 33). In her research, Curtin writes that sometimes accusations of theft were false and charges fabricated, serving as “political revenge” for emancipation. Davis continues, “In this sense, the work of the criminal justice system was intimately related to the extralegal work of lynching” (p. 34).

The drive to chase profits extends beyond just housing humans in prisons. Prison labor is exploited because incarcerated people are a captive workforce with little to no choice in what type of labor they perform and for how much. Prisoners are the cheapest labor force in the U.S.

In her book, City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los Angeles, 1771-1965 (2017) Kelly Lytle Hernández focuses on the history of the carceral state in Los Angeles, California and how caging humans furthered the goal of settler colonialism. She argues that Los Angeles is an important place to study the carceral state because the U.S. is the leader in incarceration rates in the world and Los Angeles has the highest number of humans caged within the U.S., making it the metropolitan area which incarcerates the most people in the world. Hernández's book also aims to tell the story of how Los Angeles was built with prison labor via convict leasing and chain gangs. For example:

On the chain gang, they graded the intersection of First and Flower streets. They filled in the western approach to the bridge on Buena Vista Street. They graded the intersection of Flower and Courthouse streets. By December 1887, the city council was rejecting bids from private contractors and instead deploying the chain gang to build roads and fix bridges. At the end of Workman’s term in January 1888, the city chain gang had participated in the paving of eighty-seven miles of city streets in Los Angeles (p. 58).

Convict leasing is the selling of prisoners' labor to the highest bidder by the prison; historically African American men have been exploited through this method. Typically the labor can be exploited at the prison grounds or prisoners are taken to do the work. There was a rise in the use of convict leasing after the end of the civil war during the Reconstruction period; the usage of convict leasing was one way that forced labor continued even after the end of slavery.

Additionally in Georgia for example, chain gangs were to replace convict leasing in 1908 and were labeled reform laws (Haley, 2013, p. 53). According to the article “Like I was a Man: Chain Gangs, Gender, and the Domestic Carceral Sphere in Jim Crow Georgia,” the application of chain gangs did not reduce the number of black women being incarcerated and was used to simultaneously codify what constituted a “woman” and “female” through an intersection with race and labor (Haley, p. 53). The intention for implementing chain gangs in Georgia was to slow down competition between free labor and convict labor but chain gangs continued the same culture of exploiting incarcerated human labor.

Prison labor is also exploited in the service sector. With climate change and historic droughts impacting climate disasters, in particular wildfires. Prisoners have been used as frontline firefighters, groups called fire camps, often being underpaid, undertrained, and under-resourced. In California there are over 35 fire camps made up of incarcerated men and women who are relied on to fight these wildfires and on average earning less than six dollars a day (From Incarceration, 2022). Fire camp critics call this type of labor a modern version of indentured servitude. Moreover, when formerly incarcerated firefighters re-enter society, how does their hands-on work experience help them survive and stay out of prison? Formerly incarcerated firefighters are excluded from a clear path towards becoming a firefighter due to their convictions record. Although there has not been a clear path for trained and experienced formerly incarcerated firefighters to become paid firefighters on the outside, there is a push to validate their firefighting experience and training to be utilized to pursue a feasible career in the field. In the YouTube video titled “From Incarceration to Firefighter” a group called The Forestry and Fire Recruitment Program is focused on helping formerly incarcerated firefighters get well paying jobs with fire crews (From Incarceration, 2022).

Criminalizing Immigrants

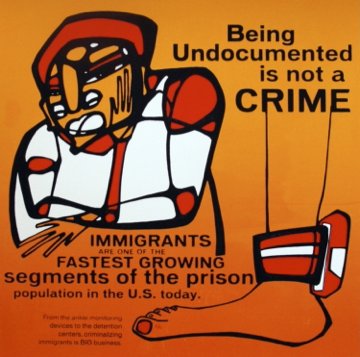

In Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) by Favianna Rodriguez, it reads "Being Undocumented is not a Crime." In her book, City of Inmates, Kelly Lyttle Hernández highlights the history of the rise of incarcerating Mexican immigrants during the 1920s and '30s in Los Angeles and simultaneously attempting to make them legally not “convicts.” One explanation was the rise of Mexican immigration due to labor demands during this time but also the “deliberate steered by particular changes in U.S. law and law enforcement, especially in the realm of immigration control” (2017, p. 131). Despite much pushback “according to the 1924 Immigration Act, an unlimited number of Mexicans would be allowed to enter the United States every year” but they were required to pay the $18 entrance fee, do a literacy test, and a health exam (p. 134). Nativists argued that Mexicans were “like the pigeon [and] he goes home to roost,” that Mexican workers did not intend to settle in the US and therefore were not interested in US citizenship (p. 135). During this time Mexicans in Los Angeles were the largest group in immigrant detention and since the “1896 decision Wong Wing v. United States, immigrant detention had lingered in the nation’s carceral landscape as a form of human confinement that was not imprisonment in the legal sense” (p.144).

The last immigration reform in the U.S. was during Ronald Reagan’s presidency through the passage of the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). Although Reagan is infamous for his neoliberal ideologies on the economy, to immigrants who benefited from IRCA he is remembered as the president who granted them legal immigration status. Undocumented immigrants who were living in the U.S. during the 1980s were able to apply for permanent residency if they were able to demonstrate that they were lawful and would not be a burden to the U.S. and use public resources. As a result, the application process included the following: paying legal fees to submit an application, provide letters of recommendation from employers, provide evidence of having access to housing, and providing evidence of being in the U.S. for the required time.

Since the passage of IRCA there has not been another comprehensive immigration reform policy. Immigrants, especially undocumented immigrants in the U.S., are criminalized for entering the U.S. without proper legal documents such as a traveling visa, work visa, permanent resident card, or passport. Although undocumented immigrants do have human rights in the U.S., because of their legal status many undocumented immigrants do not want to have any kind of interaction with law enforcement, even when they are victims of a crime. Although sometimes undocumented immigrants do report crimes, especially around the U-visa process.

Nativism, which is the belief that citizens of a country are superior over non-citizens, has fueled anti-immigration laws in the U.S. Nativist ideologies have also promoted the idea that citizens should have access to resources first, not so-called foreigners. There have been many nativist laws and policies in U.S. history barring immigrants from legally entering the country. Additionally, there have been another set of nativist laws and policies which have attempted to define the limits of access to resources for immigrants and undocumented peoples, further pushing them to the margins of society.

For example, California’s 1994 proposition 187 was designed to create a citizen screening system in order to deny immigrants access to public services such as health care and public education. Soon after the proposition passed, it was challenged and found to be unconstitutional due to the federal government having the sole jurisdiction on immigration.

In 2005, H.R. 4437 also known as The Sensenbrenner Bill or The Border Protection, Anti-Terrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act was another nativist law proposed as a method to supposedly secure U.S. borders and further criminalize undocumented people. The Sensenbrenner Bill was proposed as a result of the fight against the 9/11 attack on the twin towers in New York. A national discussion in the mainstream media emerged about the effectiveness of the U.S. border with Mexico and Canada.

Many of these anti-immigrant policies that came after the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which aimed at removing national quotas, are examples of crimmigration. Crimmigration is defined as the merging of immigration law with criminal law and posing immigrants as lawbreakers usually through a racialized lens (Sen & Mamdouh, 2008, p. 57). Some examples of crimmigration used as a modern nativist strategy are making it illegal to hire undocumented workers, The Sensenbrenner Bill, Arizona’s SB 1070, and California’s Prop 187. Rinku Sen (2008) argues that “casting foreigners as criminals protects that larger system from critique, and at the same time diverts communities from seeking real solutions” (Sen and Mamdouh, 2008, p. 58). Furthermore, through various laws and policies, crimmigration promotes the notion that an individual must be a citizen in order to be prequalified for basic civil and constitutional rights such as privacy, due process, and the right to not incriminate oneself (Sen and Mamdouh, 2008, p. 60).

A clear example of crimmigration in the US is Arizona's nativist S.B.1070 law (a.k.a. “show me your papers” law) passed in 2010. This bill not only allowed police in Arizona to work with ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) but it required that police ask any person they interact with while on duty for their immigration status, thereby encouraging racial profiling. How did this law criminalize immigrants? According to the ACLU, there were four provisions against SB 1070 considered by the supreme court. First, police demand "papers" and investigate immigration status if they suspect a person is undocumented. Second, police arrest individuals without a warrant if they believe they are a deportable immigrant. Third, immigrants who fail to carry federal registration papers are guilty of state crime. Fourth, immigrants who seek or accept work without authorization are guilty of state crime (ACLU, 2012). Provision 1 was upheld by the supreme court and the other three were struck down (ACLU, 2012).