10.3: War on Drugs and the Age of Mass Incarceration

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 143346

- Ulysses Acevedo & Kay Fischer

The Impact of the so-called "War on Drugs"

Mass incarceration is mass elimination.

-Kelly Lytle Hernández

Alice Marie Johnson lost her job at FedEx in 1991 and eventually divorced and soon after her son died in a motorcycle accident. For these reasons and due to a gambling addiction, Johnson became involved as a drug mule. In 1993, Johnson was arrested for distributing cocaine and because of mandatory sentencing laws was sent to prison for life. Johnson claimed during the trial that she was never involved in the actual selling of cocaine as a drug mule; she was also not in the business of knowing what she was transporting. Despite having no prior convictions of distributing cocaine, she was made an example and sentenced to life.

After serving 21 years in prison, Johnson had a record of good behavior and because her conviction was non-violent, she requested to be freed earlier for good behavior.

Socialite Kim Kardashian learned about Johnson through social media. According to Kardashian's account, she felt bad for Johnson because she believed that Johnson was a victim of mandatory sentencing laws. How can this nice lady serve life in prison? Soon after learning about the case, Kim Kardashian got involved and used her social influence and network to set up a meeting with then-president Donald Trump to talk about the possible pardoning of Johnson. Kim Kardashian was successful in having Trump pardon Johnson and granting her an early release from prison. Was this a sign of a new wave of prison reform?

Although Kim Kardashian's political ability to have someone released early from prison can be inspiring, it is important to note the countless lawyers and advocates who worked day and night fighting for justice or individuals just like Johnson, but may never be released from prison because no celebrity stood behind them.

What happened to Johnson is not an isolated incident, but a part of a larger system of mass incarceration which amplified with the so-called War on Drugs. Richard Nixon's 1971 call for a “War on Drugs” made drug abuse the top political priority. During his presidency, Nixon helped the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and what would become the fight against the possession and selling of marijuana, cocaine, and crack cocaine.

The New Jim Crow and the Racial Caste System

Upon winning the Oscars for Best Original Song for the song, “Glory,” in the film Selma at the 87th Oscars in 2015, John Legend stated in his speech:

We wrote this song for a film that was based on events that were 50 years ago, but we say that Selma is now because the struggle for justice is right now….We know that right now, the struggle for freedom and justice is real. We live in the most incarcerated country in the world. There are more Black men under correctional control today than were under slavery in 1850 (Penn, 2020, para. 3).

In the 2016 documentary, 13th (directed by Ava DuVernay), Senator Cory Booker makes a similar assertion as John Legend, stating, “We now have more African Americans under criminal supervision than all the slaves back in the 1850s” (01:23:25).

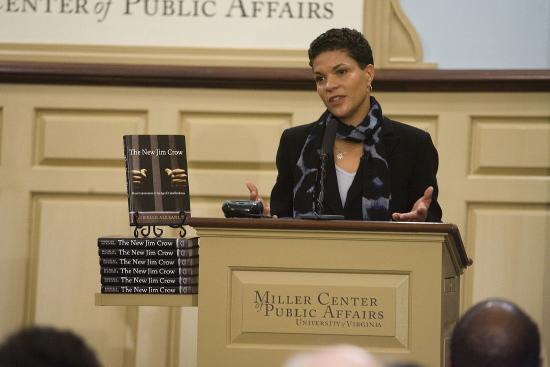

Michelle Alexander, civil rights lawyer, legal scholar, and author of one of the most groundbreaking and influential best selling books of the 21st century, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, pointed out the same, writing, “More African American adults are under correctional control today—in prison or jail, on probation or parole—than were enslaved in 1850, a decade before the Civil War began” (2020, p. 224). The 13th amendment may have abolished slavery, but it led to mass imprisonment of African Americans for minor offenses. The system of mass incarceration is what Alexander names the new Jim Crow, once the old Jim Crow policies were abolished.

Alexander explains that the War on Drugs was the “colorblind” vehicle that drove millions into the prison system, legalizing the discrimination against system-impacted people in employment, housing, public benefits, and more (2020, p. 224). Disproportionately impacting poor communities of color, the War on Drugs requires little maintenance as incarceration of poor people of color is so widely accepted by our society: it is “the new normal.” Exposed to decades of media “images of black men in handcuffs” and political messages that incarcerated people are “bad” and deserve to be there, Alexander asserts that we as a nation haven’t cared much about this injustice. If you’re white and middle class, you may not even be aware of this war. Today people of all colors “in every major political party” have internalized, even embraced, racist stereotypes of the criminality of poor people of color. The outcome is that mass incarceration is seen “as a basic fact of life, as normal as separate water fountains were just a half century ago” (p. 225).

Alexander (2020) writes that most Americans have a serious misunderstanding of how racial oppression works, assuming it’s about attitudes, never focusing on how systemic oppression can enforce a type of “racial caste system” through seemingly colorblind methods. She describes how the War on Drugs worked in three stages to cage men of color:

- Roundup: Black and Brown people are swept up into the criminal justice system due to large police presence and drug operations targeting poor communities of color. Police are allowed to use race as a factor in stop-and-search, despite the fact that people of color are no more likely than whites to be guilty of drug crimes.

- Conviction: Once arrested, poor people are denied “meaningful legal representation and pressured to plead guilty” (p. 231), as prosecutors will often add additional charges and cannot be challenged for racial bias. Once convicted, the drug war’s severe sentencing, including the impact of mandatory minimum sentencing, will lead to people spending more time under the system’s control than anywhere else in the world, including under parole or probation, described as an “invisible cage” (p. 231).

- Period of Invisible Punishment: A term coined by Jeremy Travis, this describes how formerly incarcerated people are legally discriminated against in employment and housing, leading many to eventually return to prison.

The War on Drugs has created a system that’s impacted nearly anyone who lives in ghettoized communities in the United States, reinforcing a subordinated status for poor people of color. Alexander proclaims that the nature of the justice system is, “no longer concerned primarily with the prevention and punishment of crime, but rather with the management and control of the dispossessed” (p. 233).

“Legal Misrepresentation”

Michelle Alexander argues that when an individual is arrested, their chances of being free are slim to none, largely due to the arrested being denied “meaningful” legal representation. She continues,

Most Americans probably have no idea how common it is for people to be convicted without ever having the benefit of legal representation, or how many people plead guilty to crimes they did not commit because of fear of mandatory sentences (2020, p. 106).

Despite what popular crime shows like Law & Order purport about a defendant easily accessing representation in the court system, tens of thousands go directly to jails without ever having spoken to a lawyer. Poor people are entitled to counsel, but most offices lack enough time, resources or even the "inclination" to offer competent representation. Public defense lawyers often face large caseloads and the quality of court-appointed counsel is poor due to “miserable working conditions and low pay discourag[ing] good attorneys from participating in the system” (p. 107).

Too often the most vulnerable people are pressured to a plea bargain through a threat of lengthy sentences and additional charges piled on by prosecutors, and never even go to trial. The 2004 American Bar Association reported that defendants plead guilty even if they’re innocent, not fully understanding their rights or what is happening, and there is even less regard for people who are mentally ill or who don’t understand English. Children are the least likely to have access to counsel. In Ohio, as many as 90% of children charged with crimes are not represented by a lawyer.

Prosecutors are the most powerful law enforcement officials in the system, as they are completely free to dismiss a case or add further charges as long as there’s probable cause. In fact, this is a practice known as “overcharging” (p. 109). Alexander explains,

Never before in our history, though, have such an extraordinary number of people felt compelled to plead guilty, even if they are innocent, simply because the punishment for the minor, nonviolent offense with which they have been charged is so unbelievably severe (2020, p. 109).

This pressure to plead guilty has increased since the War on Drugs. The 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act created mandatory minimum prison sentences between five to ten years for low-level drug dealing and the possession of crack cocaine. The sentence for similar offenses in other nations is no more than six months, especially for first-time offenses. The three-strikes laws have also mandated life sentences for anyone convicted of a third offense, thereby transferring power from judges to prosecutors. This practice forces arrested people to plead guilty instead of having to risk a longer prison sentence.

Furthermore, prosecutors even admit to overcharging, including for crimes that they don’t think they could win in court, but that this tactic to “load up” defendants with charges is used to pressure them to plead guilty and get them to snitch. Snitching has increased in recent years due to pressures to “cooperate” with law enforcement through cash incentives but also through obtaining testimony on another case in order to avoid a long sentence. Such testimonies are in fact “notoriously unreliable” and the U.S. Sentencing Commission has admitted that “the value of a mandatory minimum sentence lies not in its imposition, but in its value as a bargaining chip to be given away in return for the resource-saving plea from the defendant to a more leniently sanctioned charge” (p. 111). Although it is difficult to ascertain exactly how many innocent people accept a plea bargain, or how many are convicted due to faulty testimony, some sources estimate that 2-5% of incarcerated people are innocent.

Racial Disparities in Drug Charges

Michelle Alexander clearly states that “the enemy is racially defined” in the U.S.’s drug war, the main targets being African Americans from poor neighborhoods. Decades of anti-poor and anti-people of color tactics have resulted in “jaw-dropping numbers of African Americans and Latinos filling our nation’s prisons and jails every year” (2020, p. 122). The Human Rights Watch reported in 2000 that African Americans constituted 80 - 90% of those sent to prisons on drug charges in seven U.S. states. Black men are sent to prisons on drug charges at twenty to fifty-seven times the rate of white men, and nationwide, the rate of Blacks convicted of drug offenses “dwarfs the rate” for whites. The War on Drugs has affected the Latinx community as well, with their rate of drug admissions in the year 2000 being twenty-two times the number in 1983. Even whites have been impacted by the rise in prison admissions, but at a much smaller rate when compared to Black and Latinx communities (p. 123).

An obvious racial disparity of drug charges against communities of color exist despite the fact that the majority of illegal drug users and dealers nationwide are white; yet three-quarters of the people incarcerated for drug offenses are Black or Latinx. The National Institute on Drug Abuse found that white students use cocaine at eight times the rate of Black students and a nearly identical rate of white and Black high school seniors were found to use marijuana. The National Household Survey on Drug Abuse reported that white youth are more than a third likely to have sold illegal drugs than African American youth. Regardless, the arrest rates and imprisonment of African Americans have been at “unprecedented rates,” even though Blacks were not any more likely to be guilty of drug crimes compared to whites. If any group were most likely to be guilty of illegal drug possession and sales, it was white youth, who visited the emergency room for drug-related causes at three times the rate for African Americans.

Despite the racist Hollywood trope of Black drug dealers and users, Alexander writes that “the prevalence of white drug crime…should not be surprising. After all, where do whites get their illegal drugs?” (p. 124). They don’t drive to the so-called ghetto to purchase drugs from the open-air market; they sell and buy from people of their own demographic. The former director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, Barry MacCaffrey, stated that if your child purchased drugs, “it was from a student of their own race generally” (p. 124).

Knowing this, why are Black and Latinx men more likely to be sent to prison on drug charges? Alexander claims that such glaring disparities cannot be explained by rates of illegal drug activity in African American communities alone, nor is it a result of “old-fashioned” racism in the criminal justice system. Such openly biased ideologies are not easily accepted in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movements. Instead, there’s been a shift in the racial climate, where people who defend the criminal justice system insist that the system is colorblind - and instead point their fingers to the supposed violent crime rates in African American communities (2020, pp. 125 - 126). Yet, even when violent crime rates have fluctuated, incarceration rates continue to increase. In fact, homicide convictions make up a small fraction of the prison population growth - 0.4%, compared to drug convictions making up 61%. She goes on that “The general public seems to imagine that our prisons are filled with ‘rapists and murderers,’ but they actually account for a small minority of our nation’s prison population” (p. 126).

Furthermore, 7.3 million are under correctional control, but only 2.3 million are in prison or jail, and of the 4 million on probation, only 19% are convicted of violent offenses. A staggering majority of people on parole were convicted of nonviolent crimes, most commonly drug offenses (Alexander, 2020, p. 127). However, such facts are easily ignored, especially by “politicians, law enforcement officials, and journalists [who] routinely create the false impression that most people branded criminals have been convicted of violent crimes” (p. 128). Alexander argues that these claims perpetuate the myth that prisons house violent people, keeping everyone else safe. Instead, she claims that the system is not concerned about safety, but about the control and marginalization of dispossessed communities, as stated earlier.

The drug war has effectively targeted people of color, creating what Alexander calls a “new racial undercaste - a system of mass incarceration that governs the lives of millions of people inside and outside of prison walls” (p. 129). And how might such a colorblind system lead to racist results? Alexander writes that it turns out that this happened very easily in two stages:

- First, through the granting of “extraordinary discretion” to law enforcement;

- and second, by making it virtually impossible to challenge racially discriminatory practices in the criminal justice system.

When police are given free rein to decide who to suspect and arrest, prosecutors given the full discretion to make drug charges, this ostensibly guarantees that both conscious and unconscious racial bias will influence decision making. Such policies also encourage law enforcement to increase their arrest and conviction rates, even when drug crimes are slowing down in certain communities, ultimately having “guaranteed racially discriminatory results” (Alexander, 2020, p. 131). A multitude of studies and surveys show that most Americans have violated drug laws, yet only a tiny fraction are ever arrested and incarcerated. Given that the sale and purchase of drugs are consensual with no reason for either party to contact the police, law enforcement often take a proactive approach and make strategic decisions about which communities to target, often influenced by the political climate.

For example, even before crack cocaine hit the streets, the Reagan administration of the 1980s started a media campaign to build support for the War on Drugs, often highlighting horror stories involving Black crack users and drug dealers. At its onset, most Americans weren’t generally interested in drug use as it was considered a private and public-health issue, but Reagan’s campaign helped to reframe drug-use and dealings as a threat to national order. After the War on Drugs was formally launched, the frame focused on “transgressors,” who “were poor, nonwhite users and dealers of crack cocaine” (Alexander, 2020, p. 132).

Suddenly law enforcement became experts on drugs and called for “law and order.” The evening news was filled with stories about Black drug criminals who, “left little doubt about who the enemy was in the War on Drugs and exactly what he looked like” (Alexander, 2020, p. 132). A 1995 survey found that when asked to “envision a drug user and describe that person to me,” 95% of respondents reported that they imagined a Black drug user, contradicting the reality that whites make up the majority of drug users (p. 133). Law enforcement are equally influenced by such “racially charged political rhetoric and media imagery associated with the drug war” (p. 133). Research on cognitive bias show that conscious and unconscious bias can lead to discriminatory practices, even if an individual doesn’t want to discriminate. This can apply to jurors and law enforcement officials even among individuals who believed in treating everyone equally under the law. Therefore, Alexander argues, it was ultimately inevitable that racial bias would shape the drug war, particularly after “blackness and crime, especially drug crime, became conflated in the public consciousness” (p. 135)

The second main reason we have racial discrepancies in drug charges against people of color is due to major court decisions that have made it enormously difficult to challenge racial discrimination in the criminal justice system. Alexander (2020) writes how the Supreme Court adopted “legal rules” that ultimately “maximized” racial discrimination. The 1996 Whren v. United States declared that police officers are allowed to use minor traffic violations as the reason to stop any driver and search the vehicle or driver for drugs.

The 1987 McCleskey v. Kemp Supreme Court ruling declared that racial bias in sentencing could not be challenged under the Fourteenth Amendment without obvious evidence of conscious, discriminatory intent. This translated to the Court condoning racial bias as long as no one actually admitted that they were consciously acting in a biased and discriminatory manner. This ruling made it impossible to charge patterns of racial discrimination despite surging evidence. For example:

- In Georgia, prosecutors sought the death penalty in 70% of cases involving Black defendants and white victims, but only for 19% of cases involving white defendants and Black victims (Alexander, 2020, p. 138).

- In California, a 1991 study of 700,000 cases showed that whites were much more likely to get a plea bargain than African American and Latinx defendants (p. 148).

- A 2000 report presented that Black youth were six times more likely than white youth to be incarcerated for the exact same crime among those who’ve never been sent to juvenile prison before (p. 148).

Alexander reminds us that prosecutors have the most power in the criminal justice system, as they are free to dismiss a case, file more charges, offer a good plea deal or not, and have the power to transfer drug defendants to the federal system, and juveniles to adult court. It’s almost impossible to prove racial bias without evidence of “explicitly racist remarks” having been made. Alexander concludes that “It is difficult to imagine a system better designed to ensure that racial biases and stereotypes are given free rein - white at the same time appearing on the surface to be colorblind - than the one devised by the U.S. Supreme Court” (p. 149).