10.6: School-to-Prison Pipeline

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 143349

- Ulysses Acevedo & Kay Fischer

Punishing Children

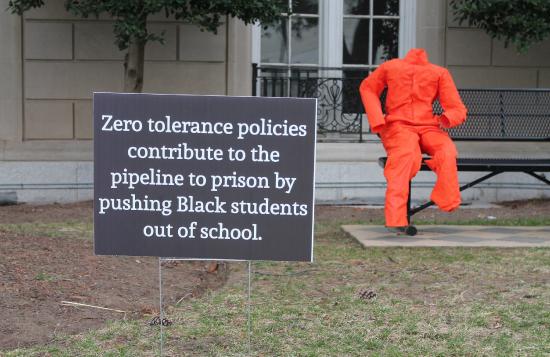

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) is a photo of an art installation by Ndume Olatushani. Pictured is a stuffed orange jumpsuit placed in a sitting position on a bench with a sign reading: "Zero tolerance policies contribute to the pipeline to prison by pushing Black students out of school." Angela Y. Davis wrote: “When children attend schools that place a greater value on discipline and security than on knowledge and intellectual development, they are attending prep schools for prison” (2003, pp. 38 - 39). This is what many today now call the School-to-Prison Pipeline, a metaphor for the manner in which disproportionate methods of punishment are enforced against students of color, LGBTQ, and Disabled students, which often lead them to be entangled in the criminal justice system. How did we get here?

Alex S. Vitale wrote that trends in the late 1990s toward harsher punishment and the rise of prisons, in combination with the increased presence and role of School Resource Officers (SROs), have contributed to this problematic pattern. The phenomenon of children being policed in schools multiplied over the last twenty years and by 2017, 40% of all schools had police officers present on campus, and involved in school discipline enforcement rather than just maintaining security. The rise of SROs was due to our Justice Department’s “Cops in Schools” program which contributed $750 million to hire 6,500 school police. Vitale continues:

While many of these officers work hard to maintain a safe environment for students and to act as mentors and advisors, the overall approach of relying on armed police to deal with safety issues has led to a massive increase in arrests of students that fundamentally undermines the educational mission of schools, turning them into an extension of the larger carceral state and feeding what has come to be called the school-to-prison pipeline (pp. 55 - 56).

Several reasons contributed to the justification of adding police in more schools, including a theory argued by conservative criminologist John DiLulio in the 1990s that the U.S. would be met by “a wave of youth crime driven by the crack trade, high rates of single-parent families” and other racist stereotypes used to blame supposed declining values. DiLulio argued that these youth were “hardened criminals,” quoting then-district attorney of Philadelphia, Lynne Abraham, who warned of “...elementary school youngsters who pack guns instead of lunches” with “absolutely no respect for human life” (Vitale, 2017, p. 56; DiLulio, 1995, para 2). This is the same DA who’s nickname was “the Queen of Death” for the unusually high number of death sentences she pursued during her tenure (Pilkington, 2016, para. 21). Such ideas were motivated by racist assumptions that are completely baseless and proven false since juvenile crime declined over the years. Regardless, the “superpredator” myth remained and led to new laws that more easily led to the caging of children and increased police presence in schools.

Another justification for increased policing of school children was the Columbine school shooting in 1999 in a white middle-class community. Two white high school students massacred twelve students and a teacher even though there were armed police on campus. The general response was to “get tough on crime,” calling for more armed police in schools, and ignoring the “underlying social issues of bullying, mental illness, and the availability of guns” (Vitale, 2017, p. 57). This, plus more punitive measures including “zero tolerance,” led to increased rates of suspensions, expulsions, and arrests often based on little evidence and for very minor offenses.

Next, Vitale argues that the rise of “neoliberal school reorganization” prioritizing high-stakes testing, led to reduced school budgets and an enforcement of more punitive disciplinary policies. With the survival of schools and teacher pay being based on testing outcomes, “a pressure-cooker atmosphere” was developed, pitting student interests against those of teachers and administrators. Administrators were motivated to “get rid of” students who “dragged” the school’s scores due to low performance or disruptive behavior, giving them a substantial incentive to drive out students through suspensions, expulsions, or by letting them drop out.

Testing and Suspensions

Unfortunately, along with the reshifting of priorities on high-stakes testing in our schools, came the dismantling of the arts and also individualized learning. Students grew listless and uninterested, leading to more discipline problems in the classroom. There was a rise in suspension and expulsion rates, even arrests of students, helping to push youth into the criminal justice system.

In North Carolina, short-term suspension rates increased by 41% and long-term by 135%; racial disparities existed in suspension rates, as Black students were 3.5 times more likely to be suspended. By 2008, twice the number of SROs were employed, leading to over 16,000 arrests of students (Vitale, 2017, p. 58). The state of Florida adopted high-stakes testing by the late-1990s and out-of-school suspensions increased by 20% by the year 2003. In the next year, 28,000 students were arrested at school, a majority for reasons that were minor offenses that previously would have been dealt with by school staff. More students were classified as disabled, being taken out of the testing pool and graduation rates fell to 57% by 2006, the 4th lowest in the U.S (p. 58).

Vitale points out Texas as being at the “epicenter of this transformation…where privatization and drastic cuts to the public sector [met] the expansion of punitive mechanisms of social control” (2017, p. 58). Zero-tolerance policies supported the removal of low-performing and disruptive students from the school, and “suspension rates went through the roof - 95 percent of them for minor infractions” (pp. 58 - 59). By 2010, the state of Texas had 2 million suspensions, a vast majority for “violating local code of conduct.” Called “supermax schools,” by journalist Annette Fuentes in her ground-breaking book, Lockdown High (2013), she argued that these schools, backed by for-profit corporations with ties to Republican leaders, acted more like prisons than places of learning. Implementations of fingerprint scanners, metal detectors, surveillance, and punitive disciplinary systems treated students as criminals, and suppressed youth rights and educational freedoms. The scarce external evaluations of these schools “found terrible performance and prison-life conditions” (p. Vitale, 2017, p. 59).

Vitale continues that, “The ultimate expression of this transformation in education is the charter-school movement, which fully embraces high-stakes testing and punitive disciplinary systems” (p. 59). This allowed even less experienced teachers to be hired and led to even more restrictive and punitive rules that continued to target the removal of students who may have lowered the school test scores. Vitale cited a PBS NewsHour segment in 2015 that found a charter school suspending kindergarten students. A principal at Success Academy, part of the largest charter school network in the city of New York, suspended 44 kindergartners and first graders in 2014. The CEO of Success Academies, Eva Moskowitz defended this practice, stating, “If you get it right in the early years, you actually have to suspend far less when the kids are older, because they understand what is expected of them” (PBS NewsHour, 2015). Some Success Academy schools had a suspension rate of 23%, while the public school suspension rate was 3%. Some parents were threatened with calls to the police if a child’s behavior didn’t improve (Vitale, 2017, p. 60). He pointed out that this inevitably pushes out a high rate of students and the charter school system can claim a high graduation rate since students leave voluntarily.

Schools as Prisons

Boarding Schools enrolling kidnapped Native American children should be recognized as one of the first systematic ways that children of color have been incarcerated and punished in schools. To learn more, see Chapter 4, section 4.4 under "Assimilation, Boarding Schools and Adoption."

Today, schools are resembling prisons more and more, and relying on punishment of school children. Further, patterns of increased punishment in schools have coalesced with the rise of mass incarceration in general over the past few decades. In the setting of the rise in “three strikes” laws and mandatory minimum sentencing, President Bill Clinton instituted the Gun-Free Schools Act, preceded by “zero tolerance” school policies, and an overall increase of harsher punishment, metal detectors, video surveillance, and more school police. Vitale wrote that such policies actually “led to the growing criminalization of young people, despite falling crime rates” (2017, p. 61). The Department of Education, for example, reported that 92,000 arrests were made in the 2011-2012 school year and a study by the Justice Policy Institute expressed how campuses with SROs had five times the arrest rate of schools without SROs, even after controlling for the race and income of students.

Sidebar: graph on arrest rates at schools with SROs

Check out Vox's 2015 article, "The school-prison-pipeline, explained" and scroll down to a graph by Justice Policy Institute. The graph demonstrates how schools with SROs have higher arrest rates of students, showing that the presence of school police only serve to criminalize student behavior.

The impact of such practices have been disastrous for marginalized students, especially students of color, students with disabilities, and LGBTQ students. Vitale reported that schools with more students of color are more likely to have these policies set in place and produce higher suspension, expulsion, and arrest rates. In a 2011-2012 survey by the U.S. Department of Education, they found that Black, Latinx, and special-needs students were disproportionately vulnerable to criminal justice actions in schools. Black students made up 27% of those referred to law enforcement, despite only making up 16% of school enrollment, and 31% were subject to arrests. White students made up 51% of school enrollment, yet only made up 41% of those referred to law enforcement and 39% arrested. In Chicago, Black students were 27 times more likely than white students to be arrested, and more than half were children under the age of fifteen (2017, p. 61). The arrests are often for small acts of disobedience or disruptions like using one’s cell phone or disrespecting a teacher.

Vitale found that schools with SROs were more and more likely to turn over disciplinary actions to the police, “...finding it easier just to have a police officer come in and remove and arrest a student than to put in the hard work of establishing a reasonable classroom environment through enlightened disciplinary systems” (2017, p. 62). Creating an effective school environment takes time, work, and resources, and Vitale points out are “a lot cheaper than paying for extra armed police” (p. 62).

Similarly, suspension rates are racially disproportionate. A 2010 study by the Southern Poverty Law Center of 9,000 middle schools reported that 28% of Black male students were suspended three times as often as white male students. Black female students were suspended at four times the rate of white female students. Special needs students are targeted as well. The Children’s Defense Fund, Ohio found similar disproportionate rates, with Black students being four times more likely than white students to be suspended. Vitale notes similar results in studies all across the nation (2017, p. 62).

A 2022 investigative report by ProPublica found that Gallup-McKinley County Schools in New Mexico state, which enrolls more Native American students than any other public school district in the U.S. (most of them Navajo), disproportionately disciplined Native students compared to white students. The district alone was responsible for at least 75% of Native expulsions statewide, while in the entire state of New Mexico, the expulsion rate for Native students was 13 times the rate for white students from 2016 - 2020 (Furlow, 2023; Jacobs and Furlow, 2022). According to ProPublica and New Mexico In Depth’s analysis, “Students in Gallup-McKinley schools faced 735 disciplinary incidents involving law enforcement” (Furlow, 2023, para 22) four times the rate for the rest of the state. See also "Indian Education" under Chapter 4, section 4.5 Perspectives and Future Directions.

Girls of Color

As mentioned earlier, controlling images scrutinize Black women as criminal, immoral, to be punished, so that violence against Black women is normalized. This unfortunately extends to Black girls in school who are framed as “insubordinate,” “disrespectful,” and “oppositional.” Monique Morris’s Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in School (2015), reveals many instances of young Black girls being criminalized, including several stories about six and seven year-olds getting arrested in school (Ritchie, 2017, p. 74). Jaisha Aikins was only 5 years old in 2005 when she was handcuffed and arrested in her school at St. Petersburg, Florida for essentially throwing a temper tantrum, something every 5-year-old does. Administrators claimed she “punched” the vice principal when video clearly demonstrated the vice principal wasn’t hurt. After three fully grown white police officers arrived at the school, they handcuffed this kindergartener as she cried and begged them not to. She was only released to her mother after the prosecutor refused to file charges.

The New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) uncovered several instances of young women of color getting physically handled by school police for minor things like leaving class a few minutes late or cursing in the hallway. Ritchie refers to another instance where 16-year-old Pleajhai Mervin was slammed on a table by a school safety officer in Palmdale, California, for failing to pick up cake from the cafeteria floor. The officer yelled, “Hold still, nappy head,” as he held her down (2017, p. 75). On October 26, 2015, a viral video revealed a shocking incident of a school resource officer in South Carolina grabbing a young Black high school student by her neck and flipping her desk while she was sitting in it. He slammed her head on the ground then dragged both the girl and desk toward the door. Sixteen-year-old Shakara was sitting calmly at her desk when the officer, Ben Fields, demanded that she leave the classroom. He escalated quickly to physically assaulting her when she refused to comply, resulting in injuries to Shakara’s neck, shoulders, and arm before placing her under arrest. Another young Black woman at the school, Niya Kenny protested this treatment and also was arrested. Both were charged with “disturbing school” (p. 72).

Due to protest and outrage expressed on social media, the charges against both girls were dropped and the officer was fired, but no charges were brought against Fields. Ritchie notes that this attack in particular “exemplifies how zero-tolerance policies…place disagreements between students and teachers, regulations of classroom behavior, and enforcement of school rules in the hands of armed police officers stationed in public schools, creating opportunities for violation and criminalization of young Black women” (2017, p. 73). The increased police presence in schools have led Black girls to be the fastest growing group to face suspension and expulsion as part of the school-to-prison pipeline. They make up around 33% of girls referred to law enforcement despite only making up 16% of the female student population, yet, Ritchie writes, “the discourse around…the ‘school-to-prison pipeline’ continues to focus nearly exclusively on boys and young men” (p. 77).

Ritchie also points out that Native youth are impacted by the school-to-prison pipeline as well, who are three times more likely to be referred to the police than white students. In Utah, for instance, Native students from kindergarten to sixth grade were referred to law enforcement more than any other group. Young Native women are five times more likely than white girls to be detained in juvenile hall. In South Dakota, the Rosebud Sioux nation successfully filed a suit challenging arrest practices in schools targeting Native girls. In one example, 13-year-old Mindi struck a white girl at her school after she scratched and cursed at her Native friend and the two Native American girls were arrested while the white girl was not. Mindi was charged with “disturbing school” and “disorderly conduct” (2017, p. 79). In another instance, Josei Traversie was arrested for defending herself against students who spit on her, placed on probation, then held in a juvenile detention center.

Sexual harassment and assaults by police officers on campuses also impact girls of color including inappropriate comments about their bodies, or degrading and violating pat-downs by male officers through security checkpoints. Jacquia Bolds from Syracuse, New York testified to a UN committee in 2008, “It is more uncomfortable for girls because sometimes they check you around your most private areas” (Ritchie, 2017, p. 80). A 14-year old Chinese American student stated, “The security guard accused me of having a knife….They took me to a room and made me take off my shirt and pants to check my bra. They didn’t call my parents or let me talk to a teacher I know” (p. 81). Muslim students shared that school safety agents would pick on girls wearing scarves and hijabs, one stating, “For some of us…it’s like you’re covered up too much” (p. 81). In one survey, young South Asian women shared that they experienced gender-based and sexual harassment by school police who made lewd comments during security checks, and almost half of the surveyed stated that they were asked about their immigration status. Sadia, a 17-year-old Pakistani woman shared, “I am in constant fear that my immigration status will be revealed” (p. 82).

Young women of color are organizing against police violence directed toward them, both inside and out of schools, such as calling for an end to school policing, decriminalizing offenses, or closing jails. Ritchie calls for action by writing,

It is our responsibility to create spaces in which girls’ and young women’s experiences of policing can be seen and heard, and to support their leadership and their demands to get police out of schools…and promote conditions under which young women of color can be safe and thrive (2017, p. 87).

Special Needs Children

Students with special-needs, who have physical or learning disabilities, are also disproportionately represented among students referred to law enforcement at about 26% while they only make up 14% of the entire student population. Black and Latinx students are referred in disproportionate numbers to their enrollment rate (Ferris, 2015; Vitale, 2017, p. 62). In 2015, an 11-year-old African American student with autism from Lynchburg, Virginia, Kayleb Moon-Robinson, was charged with criminal offenses by the school’s SRO multiple times. Once for kicking a garbage can and another time for resisting the officer who was trying to grab and drag him out of the classroom. The student was charged with a misdemeanor for disorderly conduct and a felony for assaulting a police officer and a family court judge found the child guilty of all charges (Vitale, 2017, p. 62).

Kayleb stated that the school police, “...grabbed me and tried to take me to the office…I started pushing him away. He slammed me down, and then he handcuffed me” (Ferris, 2015). A teacher confirmed that the officer grabbed Kayleb’s chest and he cursed and struggled. School officials only defended the presence of police in schools. Kayleb’s mother, Stacey Doss shared, “I thought in my mind - Kayleb is 11…He is autistic. He doesn’t fully understand how to differentiate the roles of certain people” (Ferris, 2015). In the same report Ferris found that Virginia schools referred students to law enforcement at nearly three times the national rate. The Center for Public Integrity found that thousands of complaints filed in courts against students were mostly for disorderly behavior and against preteens or middle school students.

In another incident, a 12-year-old girl from Virginia was charged with four misdemeanors including “clenching her fist” at a school police officer. In Green County, Virginia in 2014, the school police handcuffed a 4-year-old child for throwing blocks and kicking at teachers. He was driven to the sheriff’s department. In August of 2015, a Kentucky sheriff’s deputy handcuffed two disabled students, an 8-year old and 9-year old for minor disorderly behavior that were related to their disabilities and for one child, related to trauma (ACLU, 2015; Vitale, 2017, p. 62). Video footage of the arrested third-grader showed that his arms were so small that the officer had to handcuff his biceps behind his back, as he cried, “Ow, that hurt” (ACLU, 2015). The ACLU filed a lawsuit and explained that this particular child who was filmed was crying out in pain for 15 minutes. They also stated that disabled students made up 75% of all students subject to physical restraint at school according to the U.S. Department of Education. The ACLU pointed out that the school’s reliance on armed police to manage the behavior of special-needs students was a “fundamental violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and civil and human rights” (Vitale, 2017, p. 63). In the video description, an update from October 13, 2017 states that a federal judge in Kentucky found this act of cuffing disabled students unconstitutional and Kenton County is liable for the deputy sheriff’s actions.

Being arrested and charged is an introduction into the school-to-prison pipeline for students. It can create a record that further stigmatizes special-needs students at schools. Judges can order them to conduct community service, meet with probation officers, wear electronic monitors and place students in detention before and after a hearing, essentially criminalizing youth in a severe matter with serious life-long consequences.

The Autistic Self Advocacy Network reported that all charges against Kayleb were eventually dropped after petitions were filed in defense of Kayleb and most likely because his story got some media attention (Autistic Self Advocacy Network, 2016). This should be celebrated, but how many more thousands of children are punished cruelly and unnecessarily every year in our schools, just for having disabilities?

Militarization of Schools

Those glued to the TV or social media in the summer of 2014 witnessed armored tanks and police in military gear pointing semi-automatic rifles at protestors in Ferguson, Missouri. Large demonstrations demanded justice for Michael Brown, who was killed at only 18-years of age by Ferguson Police Department officer Darren Wilson on August 9, 2014. The protest scenes looked more like a war battle scene. Since when did local police forces have access to such military equipment, typically used in a war? One analysis by National Public Radio found that the Pentagon has given local police forces close to $2 billion of military-grade equipment like mine-resistant vehicles, assault rifles, and grenade launchers. In the case of Ferguson Police, they received gear from private companies including computers and utility trucks at Urban Shield (Bauer, 2014, para. 7).

Funded through a counterterrorism grant from the Department of Homeland Security, Urban Shield claimed to be the largest first-responder training in the world, bringing in people from across the globe including Israel and South Korea. Started by the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office in California, Urban Shield offered militarized police training and a weapons expo and also received funding from over 100 corporations including Verizon, Motorola, and military supply companies (Critical Resistance; Bauer, 2014, para. 4-5). Urban Shield in Alameda County was stopped in 2018 due to the grassroots organizing and legislative advocacy amongst various community organizations, most notably under the Stop Urban Shield Coalition.

Mother Jones reported that “outfitting America’s warrior cops” is major business, with the Department of Defense having given $5.1 billion worth of equipment to local and state police departments since 1997, and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) giving out $41 billion since 2002 in the form of grants, specifying that they can be used to shut down protests, serve warrants, and search homes (Bauer, 2014, para 7). Such programs have led to the proliferation of SWAT teams and raids, the ACLU finding that SWAT raids were more likely to hit Black neighborhoods than white neighborhoods (Lopez, 2016, para 7).

Vitale reported that school police are also joining in and purchasing military-grade equipment and weapons including AR-15 assault rifles, shot guns, and mine-resistant ambush protection (MRAP) vehicles, and school children in largely Black or Brown neighborhoods are facing SWAT raids as well (2017, p. 63). In 2003, Goose Creek High School in South Carolina coordinated a massive SWAT raid for drugs and guns. Police had their guns drawn out, brought in police dogs, searched students, and ordered the largely Black student body to get on the ground. No drugs were found. Vitale wrote, “The use of guns and militarized equipment undermines the basic ethos of school as a supportive learning environment and replaces it with fear and control” (p. 63). He stated that the National Association of School Resource Officers has become the “bastion of this process,” where at its annual conference we can find military contractors selling schools security systems and training officers in paramilitary techniques. Once a keynote speaker at this conference told the audience:

You’ve got people in your schools right now planning a Columbine….we have Al-Qaeda cells thinking of it. Every school is a possible target of attack...You’ve got to have enough guns and ammunition and body armor to stay alive...You should be walking around in school everyday in complete tactical equipment, with semi-automatic weapons and five rounds of ammo...You must think of yourself as soldiers at war (p. 64).

The Southern Poverty Law Center filed a class-action lawsuit in 2010 against Birmingham, Alabama schools for systematically using excessive force on students, alleging that close to 200 students were sprayed with pepper spray and tear gas, causing extreme pain, skin irritation, and problems with breathing and vision. All the students targeted were Black, one student was pregnant, and many were bystanders. The school district was found guilty in 2015 and the use of sprays were banned (Vitale, 2017, p. 64). In 2013, a Texas student, Nino de Rivera was tasered by a school resource officer and critically injured by the resulting fall and blow to the head. He had to have surgery to repair a “severe brain hemorrhage” and was in a medically induced coma for 52 days.

In 2015, Mother Jones reported that at least 28 students had been seriously injured between 2010 and 2015, in one case a student was shot to death by an SRO. They reported that there is a lack of government data on police conduct in schools and they seem to lack training and oversight, disproportionately impacting students of color and disabled students (Lee, 2015, para 1-2). At a middle school in Louisville, an officer punched a 13-year-old student in the face for cutting the cafeteria line, and the same officer put another middle-schooler in a chokehold, knocking him unconscious (para 3). In May of 2014, a high school student in Houston, Cesar Suquet, was hit at least 18 times by a baton by police officer, Michael Y’Barbo (para 4). On November 10, 2010, 14-year-old Derek Lopez punched another student outside Northside Alternative High School near San Antonio, Texas. Officer Daniel Alvarado witnessed the event, ordered Lopez to freeze, then chased Lopez to a shed behind a house and shot him, ending Dreke Lopez’s life. Lopez was unarmed, yet the officer claimed he “bull-rushed” the officer. A 2012 grand jury declined to indict Alvarado (para 6).

Vitale wrote that there is no evidence to suggest that the presence of School Resource Officers (SROs) reduce crime, or reduce thefts or violence. There’s only been a few instances where officers averted a potential gun crime. In fact, schools with police presence report that they feel less safe than similar schools with no police (2017, p. 65). Data show that reported crimes increase with more SROs, partially because they treat more things as criminal matters.

Ultimately, schools are places of learning and student learning improves when students feel safe and supported. Even well-intentioned school policing and punitive discipline practices undermine that, because it can create a climate of distrust which can increase disruptive behavior. Armed police have not shown to improve the safety of students and won’t protect schools from intruders. School Resource Officers are mostly effective at driving out youth from schools and into the criminal justice system. Vitale summarized, “Our young people need compassion and care, not coercion and control” (2017, p. 73).