11.2: Frameworks for Action

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 143353

- Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick & Kay Fischer

Ethnic Studies in Action

In Ethnic Studies, there are multiple frameworks for action to address the complex process of dismantling structural hierarchies and working toward racial justice, decolonization, and equity. Activism has driven the field and community action is a recurring principle in Ethnic Studies classrooms and scholarship. These frameworks reflect the different standpoints that advocates and community organizers bring into the process of creating change and how activism takes place. The picture included in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), "I Get it From My Mama" by Melanie Cervantes highlights the importance of intergenerational knowledge in shaping social movement activism.

Indigenous Sovereignty

Indigenous sovereignty refers to the self-determination and legal standing of Native and Indigenous peoples. Sovereignty is distinct from other forms of justice because it refers to the historical relationship between peoples and governments, including the system of government within a particular society or territory. Sovereignty is an explicitly political project that concerns land rights, treaties between tribes and other governments, including the United States, and the political standing of Native Americans and Indigenous peoples. Sovereignty is also a matter of economic capacity and spiritual integrity. Native and Indigenous peoples work to ensure that there are resources to support and grow self-determination, as well as the continuation of cultural, religious, and spiritual traditions that sustain political processes and traditional knowledge.

The project of decolonization refers to the continued struggle to assert and restore tribal sovereignty in the face of settler-colonialism and systems of genocide. Decolonization is a far-reaching agenda that requires us to commit to changing how we think about ourselves and our history, in tandem with political and cultural advocacy that affirms sovereignty (Tuck and Wang 2012).

Queer and Trans of Color Critiques and Intersectionality

Intersectional and queer of color approaches to collective action have worked to address justice for historically minoritized and exploited groups by focusing on those who experience multiple forms of oppression. The term intersectionality was coined by Kimberle Crenshaw (1989) to describe the unique experiences of Black women, whose claims of illegal discrimination based on race and sex were denied in the court system. Beyond the legal system, intersectionality has been used to highlight how mainstream narratives erase the unique experiences of women of color and other multiply marginalized groups. The notion of intersectionality resonated with other groups like Chicanas, Native and Indigenous feminists, and womanists, who have developed the framework for over 30 years. See also Chapter 8, section 8.2 "What is Intersectionality?"

The phrase intersectionality is a key term for emphasizing experiences of race, gender, sexuality, immigration status, and more. The idea behind intersectionality was developed within social movements and activist communities, including within the Black feminist lesbian tradition (Lorde 2007). The Combahee River Collective statement in 1977 articulated some of the key aspects of intersectionality, including a focus on power relations, systemic oppression, and the importance of continually taking action to make change. You can read this statement in full on the Black Past website. Similarly, Brazilian Black feminists like Lélia Gonzalez also articulated these ideas long before 1989.

These key principles are also utilized in queer and trans of color frameworks (Ferguson, 2003). For example, while many are familiar with the parades and community gatherings held for Pride celebrations today, these would not have been possible without the leadership of queer and trans people of color like Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson. These figures were fearless advocates for the trans people of color and queer people of color experiencing vulnerability and risk based on discrimination and exclusion. Cisheteropatriarchy has been resisted within Ballroom culture, which provides a unique social setting for People of Color, including Black drag queens, to celebrate diversity and cultivate spaces to disidentify with dominant cultures (Muñoz, 1999).

Sidebar: Ballroom Culture

Ballroom culture originated in the late 20th century in big cities around the country, with Black and Latinx LGBTQ+ communities celebrating culture and community through dance, performance, and fashion. The styles of Ballroom dancing have had major impacts on popular culture, including being the source of Madonna’s Vogue and popularizing dance moves like the “death drop” that appear in RuPaul’s Drag Race and on memes circulated online. Despite this mainstream influence, many of the performers and organizers of Ball culture remain in precarious housing and economic situations, with little resources or security. The 1990 documentary, Paris is Burning, introduces Ball culture with a more serious consideration of participants’ lived experiences. More recently, the TV series Pose (2018-2021) featured a popular, fictional retelling of the inner-workings of New York City Ball culture in the late 1980s.

Disability Justice Framework

Working in solidarity for social transformation includes many groups that have been marginalized and oppressed. In addition to ethnicity, race, gender, and sexuality, people with disabilities have built movements for self-representation, advocacy, and social change using a disability justice framework. The category of disability is broad and can include physical disabilities, emotional disabilities, and cognitive disabilities. Within any of these categories, a disability may be visible or invisible, and temporary or permanent.

The group Sins Invalid has put forward a framework to organize work for disability justice, which has ten components.

- Disability justice must be intersectional and take into account the range of experiences and identities that overlap with disability experiences.

- Disability justice means centering the leadership of the most impacted individuals and communities. This means prioritizing people with disabilities based on their own perspectives and not their family members, doctors, or other “experts.”

- Disability justice means taking up anti-capitalistic politics. Capitalism places value on people based on their productivity and ability to create monetary gains, and many people with disabilities cannot or do not translate their worth in terms of paid employment.

- Disability justice is a commitment to cross-movement organizing, such as economic justice movements, racial justice, and gender justice.

- Disability justice is recognizing wholeness. This means taking a broad perspective on our humanity, and not defining people solely based on one aspect of themselves, such as a single identity. Some people with disabilities intentionally chose “person-first” language like, “people with disabilities” as opposed to “disability-first” language like “disabled people” to emphasize humanity and wholeness. Notably, some people with disabilities choose to use terms like “disabled” so that it draws attention to the process of society disabling people through active choices and policies.

- Disability justice is sustainability, meaning that at an individual, social, and environmental level, we must be able to sustain our movements and support ongoing activism.

- Disability justice is a commitment to cross-disability solidarity. This means working together across different experiences of disability. People with physical disabilities, emotional disabilities, and cognitive disabilities may have little in common within their day to day experiences, however, through intentional movement building and solidarity, everyone’s concerns can be brought together.

- Disability justice is interdependence, which involves a recognition that we are all implicated with each other. It is sometimes characterized that people without disabilities are independent and people with disabilities are dependent. However, all people are both independent and dependent, and when we recognize our interdependence, we can be more effective in supporting each other.

- Disability justice is collective access. This builds on the notion of interdependence to think beyond the individual level when considering disability issues. Collective access can mean considering how groups, families, and communities can access spaces and institutions. For example, are ramps, elevators, and sidewalk cutouts present throughout entire neighborhoods? And, which neighborhoods have these supports available in the built environment? Are caretakers and family members of people with disabilities included in accommodations and accessibility procedures?

- Disability justice is collective liberation. This emphasizes that when working for inclusion, justice, and equity, marginalized groups can support each other to reach further and create change.

Together, these principles are essential for understanding disability justice, and they can also be applied and adapted to consider a range of social issues and movement organizing.

Sidebar: Disability Advocacy and Pop Culture

Disability justice advocates help to identify when words or phrases are exclusionary to people with disabilities. For example, in June 2022, fans discovered that Lizzo’s upcoming song featured an offensive term and Twitter user @hannah_diviney posted this to express her disappointed. Many more began to join in the conversation and speak out against this particular term, along with other commonly used words that maintain derogatory meanings against people with disabilities. Lizzo revised her song and made a public apology, which was met with widespread admiration on social media. However, the reading of “spaz” as a derogatory term has been challenged by Black disabled people who recognize that it has a different history and context among Black people. However, as a non-disabled person, Lizzo acted as an ally to the people who were harmed by her word choice, a concept which is covered further in the next section.

Allies, Accomplices, and Co-Conspirators

When considering the use of these structural frameworks for sovereignty and justice, it is important to recognize that change is carried out by individual people working in community. Individuals may carry a range of marginalized or privileged statuses, including in combination. When thinking about working from the space of privileged identities, scholars and activists have described opportunities to be an accomplice, ally, or co-conspirator.

Allies are members of a dominant group who take an active role in understanding their own privilege and working to support members of a marginalized group. Some examples of actions that allies take include: educating themselves about historical and contemporary injustice, being vocal advocates for anti-racism, interrupting acts of bias, and supporting people who have experienced discrimination. There is no one right way to be an ally, but many opportunities to practice allyship when a person is operating from the standpoint of privilege. This practice builds relationships across differences and encourages listening, learning from mistakes, and continually taking action. Allies take action without centering their own identity or seeking validation of their allyhood. When individuals from a privileged standpoint recenter themselves and their own validation, they are no longer acting as an ally or working against a pattern of marginalization.

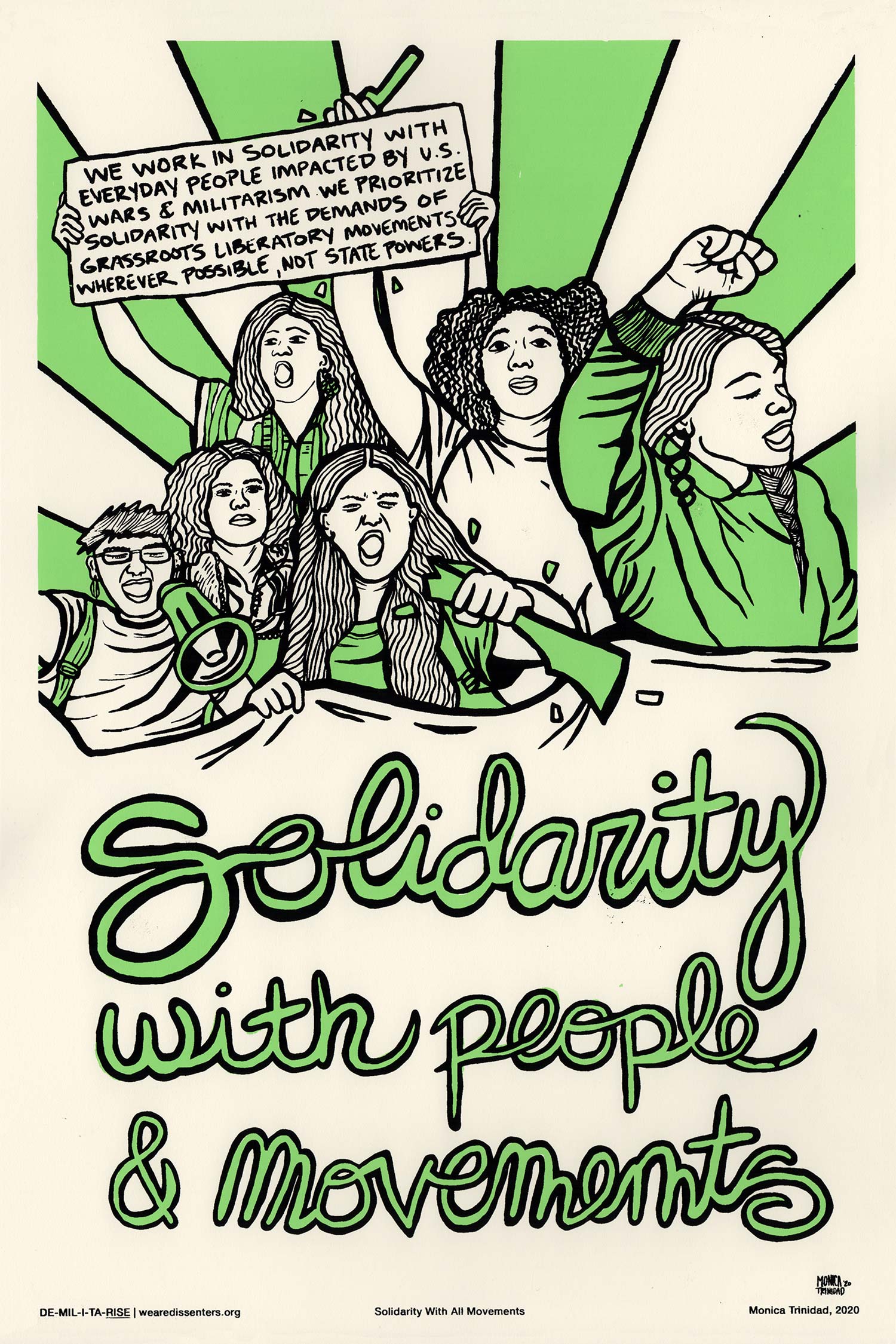

Allyship is just one component of acting in solidarity against systems of marginalization. For instance, accomplices go beyond supporting members of a marginalized group to take sustained and proactive action. This includes white people who actively work toward anti-racism, men committed to ending patriarchy, and straight/cisgender people who work against the oppression of LGBTQ+ people. Accomplices have already developed substantial knowledge and cultural humility to align their actions with the leadership and goals of marginalized group members. The concept of solidarity is visualized in the image contained at the end of this section. Another term that is often used to describe this kind of solidarity practice is co-conspirator. This refers to the necessity of working actively in continual collaboration with people of color and other marginalized groups and taking active risks to unsettle the status quo. In Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), you can see an artistic rendition of solidarity, with a group of individuals protesting together, including a sign that says, "We work in solidarity with everyday people impacted by U.S. wars and militarism. We prioritize solidarity with the demands of grassroots liberatory movements wherever possible, not state powers."

Digital Activism

The Internet has created many new opportunities for activism, social movement building, and connecting people together to help create change in our communities and society. In the early 21st century, Internet-enabled devices like computers, tablets, and smartphones became increasingly more accessible to the public. New forms of social media allowed for direct communication between individuals at a global scale without the same barriers and gatekeepers involved in broadcast media, like television, radio, and publishing. This became a major asset for activists in repressive countries with strict governmental controls, leading to events like the “Arab Spring” in 2010 and 2011, where activists staged massive protests against authoritarianism and corruption. In the United States, the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011 was an early example of social media being used to spread information about protests. You can learn more about the Arab Spring from the 11-minute radio report on NPR linked here. Occupy Wall Street originated the slogan of the “99%” for economic solidarity among working-class and middle-class communities, and you can find out more about the movement on their website linked here. The tweets that brought activists together to protest capitalism and economic exploitation in New York City quickly spread around the country and eventually the globe, spawning “Occupy” demonstrations in cities and towns where people set up camps in public places that functioned on a collectivist ethic, prioritizing horizontal leadership, as well as raising awareness about economic inequalities.

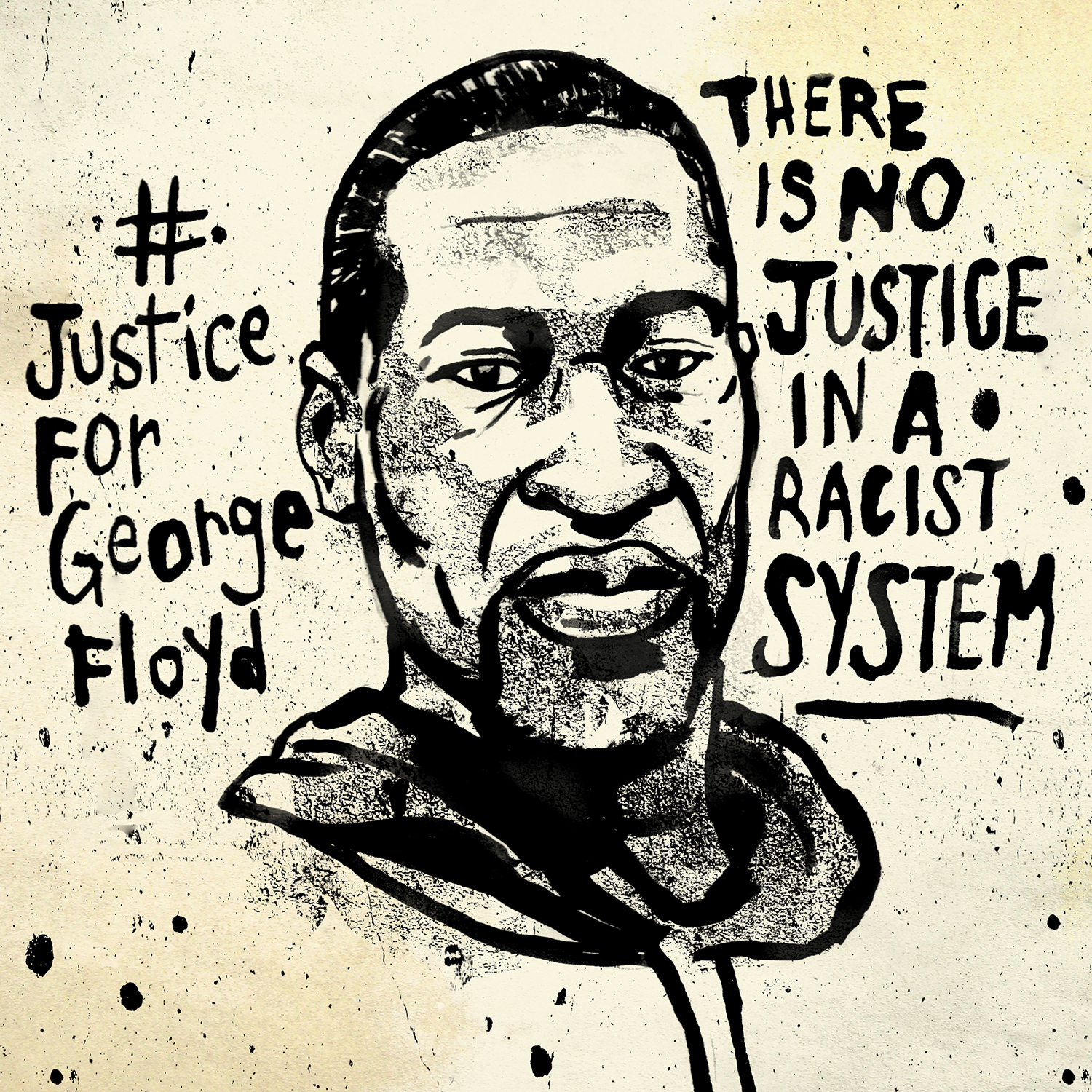

Now, digital activism is included in nearly every social movement and social justice issue. According to an article by the Pew Research Center (2021), 60% of adults in the U.S. use their smartphone, computer, or tablet often. The rising popularity of social media activism has also led to critiques of what some refer to as “slack-tivism” where people post something on social media but do not engage in sustained action beyond a single post. In these instances, digital activism is mostly seen as a performance that is disconnected from the sustained work of movement building, collective action, and social change. However, digital activism emphasizes the multiple potential targets of social movement organizing. For instance, Twitter users can post messages and start hashtags that seek to raise awareness about political issues and elections, hold corporations accountable, share and critique cultural productions, and organize public discussions. Hashtags are used to raise awareness and inspire people to join in the movement and make it their own. In Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), the artist has rendered the hashtag "#JusticeForGeorgeFloyd," demonstrating how social media conventions have permeated all forms of representation, including art.

Artistic Resistance

Arts and culture are vital domains for activism and social movements. Artistic expression can be used to communicate critiques of social institutions and authority structures and as a way of building and mobilizing collective identities. Art is a powerful communication tool and has the advantage of having multiple meanings for multiple audiences. Phrases and melodies used in hip-hop, poetry, and music of various genres can illuminate social structures and build connections in place of isolation. Art is also used to spread messages through the built environment through monuments, sculptures, murals, tagging, posters, and stickers.

For example, memorials are an important site of collective identity both for social movements and social institutions. For example, in the southeastern United States, many statues honor Confederate leaders and soldiers from the U.S. Civil War. The Confederacy existed from 1861-1865 as a last-ditch attempt to maintain the system of U.S. chattel slavery. However, many Confederate memorials and symbols are circulated both within and beyond the former Confederate states in the U.S. South. The supporters of these monuments often claim to recognize their historical or cultural value, but they communicate support for slavery and racism among white people. Similarly, in 2021, First Nations activists in Canada toppled a statue of both Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth II in response to the discovery of mass graves of Native children in the country’s Boarding Schools.

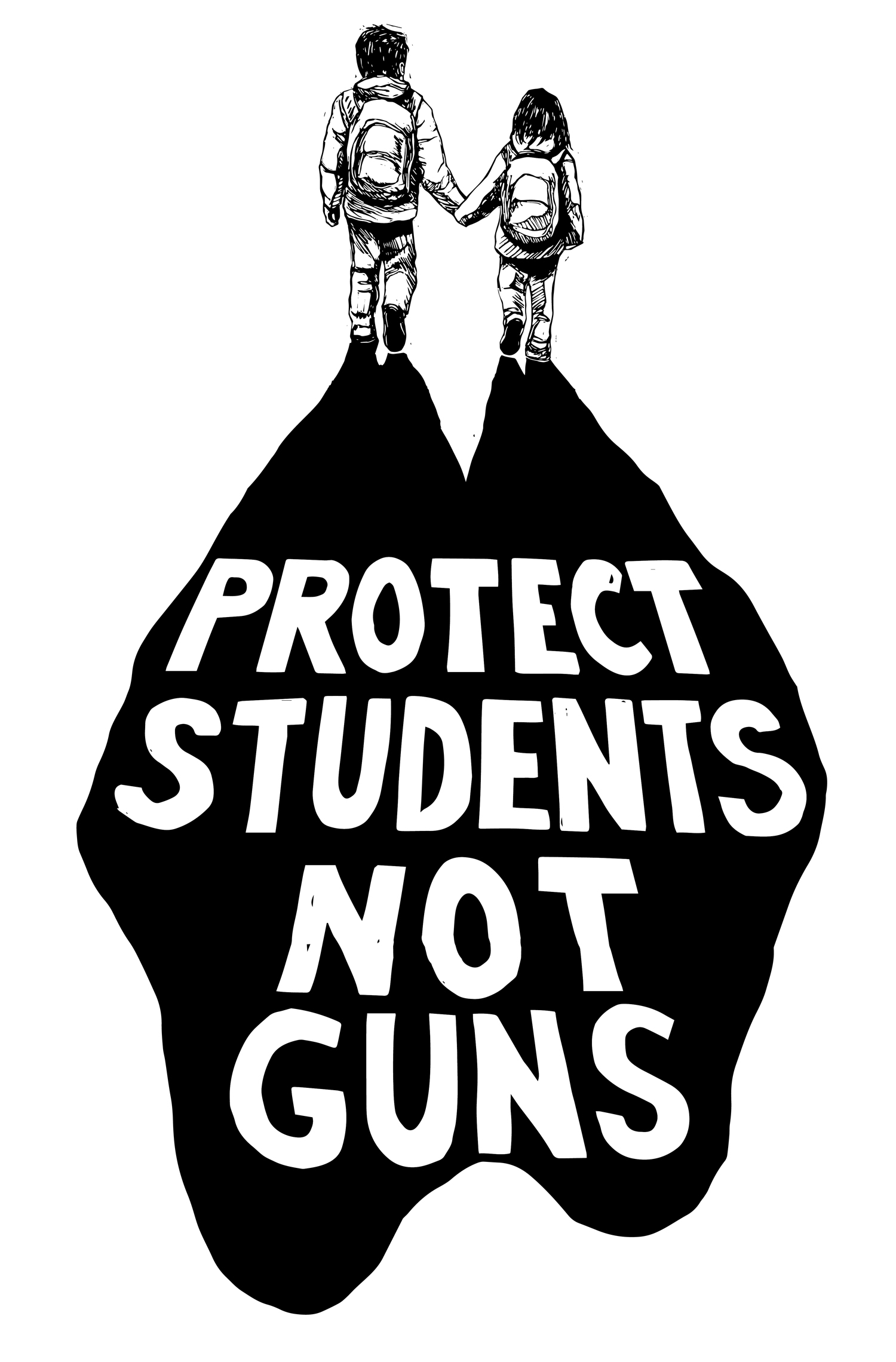

Art can be powerful in conveying messages through symbols. For example, in the image shown in \(\PageIndex{4}\), the long shadow behind students conveys the heavy weight of fear in living in a society where school shootings are normalized.

Images can also communicate complex social realities and contradictions. For example, in the activist poster in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\), a Latina migrant woman is shown looking backward over a coastal landscape with a traditional scarf, a monarch butterfly perched on her shoulder, and the circular halo associated with Catholic saints, but mirroring the color and pattern of the monarch butterfly’s wings. Accompanied by the text, “Migrar es resistencia anticolonial” (“Migration is anticolonial resistance”), this image signals a transnational identity rooted in liberation and faith.

Because of art’s ability to challenge conventional thinking and reveal important social realities, it has always been a crucial tool for social movements. One way this can be seen is that authoritarian regimes often target artists and scholars to help maintain social control and oppression. Creativity can be dangerous to those in power who seek to divide and exploit. Culture plays an important role in shared struggles over who we are, how we remember the past, and what that means for the future.