11.3: U.S. Civil Rights and Liberatory Movements

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 143354

- Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick & Kay Fischer

The Civil Rights Movement

The Montgomery bus boycott of 1955 is widely recognized as the start of the modern Civil Rights Movement in the United States, with the arrest of Rosa Parks who refused to give her seat to a white passenger. Still, it should be noted that earlier court cases, direct actions, and civil disobedience all led to the development of this movement, and Parks was not the first to refuse giving up her seat on the bus. However, Parks’ actions did lead to the Montgomery bus boycott becoming one of the most impactful boycotts in the U.S., ushering in a mass movement to dismantle the Jim Crow South and legal segregation of schools, businesses, and public transportation. The Civil Rights Movement also instituted voting rights for African Americans and other disenfranchised communities. This era culminated into significant legislative victories including: the U.S. Supreme Court decision of Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

The Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. emerged as a leader for this movement, although there were many others who haven’t been as widely recognized for their contributions including women and gay men. Bayard Rustin, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, and Septima Clark, to name a select few, played instrumental roles in what is considered one of the most effective mass movements in U.S. history.

One year since the start of the boycott, buses were desegregated following a Supreme Court ruling and Dr. King quickly became a national political figure. He established the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and led multiple nonviolent protests against “the moral injustices of a segregated society” (Paulson, 2020, p. 144). Dr. King led more than 200,000 supporters of the movement in the 1963 March on Washington, D.C., and led another major protest of the movement in 1965, marching from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama to pressure Congress to pass the voting rights bill. In most instances, peaceful demonstrators were met with violence, harassment, arrests and even death by white mobs and police.

_-_NARA_-_541994.tif.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=550&height=435)

An earlier landmark decision was the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which overturned the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling on “separate but equal” in public education, making racial segregation in schools illegal (pp. 142-143). The decision was met with severe resistance from whites, with some school districts preferring to close their schools instead of integrating with African American students. When a violent white mob attempted to stop the integration of Black students in Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, President Eisenhower sent federal troops to protect the “Little Rock Nine” (p. 143). See also "Challenges to Legal Segregation" under Chapter 2.

It is important to note that the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case was not the first to address segregation and discrimination in schools. In 1884, Chinese Americans Mary and Joseph Tape were not allowed to enroll their daughter in the San Francisco public school district because she was Chinese. The Tapes sued the school board and the landmark California Supreme Court Case, Tape v. Hurley (1884) ruled that all children, including children of non-white immigrants, were entitled to public education in the state. However, the state assembly passed a law that established racially segregated schools under a separate but equal doctrine and the Tapes' daughter, enrolled in a separate school in Chinatown that was created for Chinese and other Asian American children.

The 1946 Mendez v. Westminster case was another landmark decision challenging school segregation, and this was a crucial precursor to Brown v. Board of Education. Gonzalo Mendez (Mexican American) and Felicitas Mendez (Puerto Rican) tried to their enroll their three children in a public elementary school in Orange County but were denied because the school didn't allow Mexican Americans to attend. They and 5,000 other similarly aggrieved parents filed suit against multiple Orange County schools districts and ultimately the Supreme Court declared that segregation on the basis of a Spanish surname was unconstitutional. See also "Sidebar: Mendez vs. Westminster and Discrimination in California's Public Schools" under Chapter 2.

“Sit-ins” were another useful tactic for the Civil Rights movement, started by four Black college students protesting the discrimination of Black patrons at the local Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. These students and supporters formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1960, and they played an important role in voter registration drives.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 prohibited literacy tests and an amendment in 1970 and 1975 banned literacy tests in all fifty states permanently (p.142). Literacy tests, poll taxes, white primaries and other policies were adopted in the Jim Crow South at the end of Reconstruction as a way to eliminate the African American right to vote (p. 141).

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it illegal to discriminate on grounds of “race, color, religion or national origin,” adding the banning of discrimination in employment practices, and it was followed up by the Civil Rights Act of 1968, also known as the Fair Housing Act, which prohibited discrimination in housing.

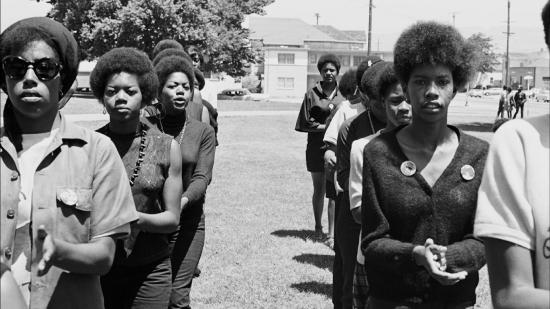

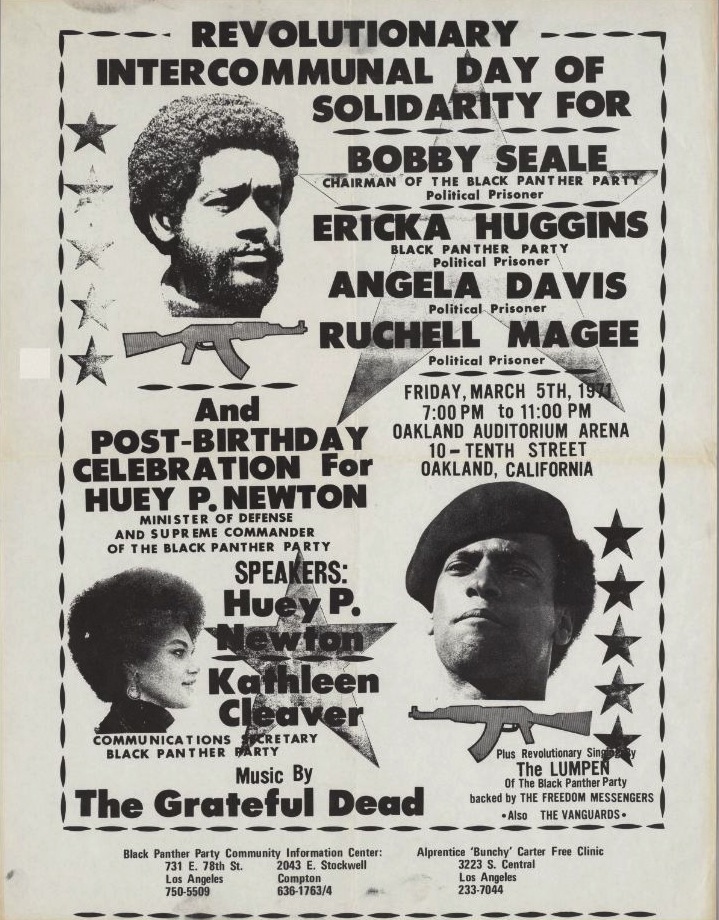

Black Panthers

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, often called the Black Panther Party (BPP) was a political organization founded in 1966 in Oakland, California by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale. The BPP was rooted in the ideology of Black nationalism, socialism, and armed self-defense, and the organization based its practices on the logic of separatism, rather than the integration approach taken by other civil rights organizations. This debate is a profound and existential one for many activists and movements, who must decide when to operate within the systems that exist and when to challenge the system as a whole and work for transformation. Stokley Carmichael was a BPP leader who led the party to form educational and social programs, in addition to political activity. Women also played an important role in the BPP, and can be seen in formation in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\).

Leaders like Bobby Seale sponsored initiatives like the Free Breakfast Program, which provided meals to low-income children, helping them to be better prepared and engaged throughout their school day. This was an effective strategy because it directly helped people in need, it demonstrated the capacity and funding for a group of people to provide and distribute food for free, and it raised awareness about one way that economic condition (the ability to provide breakfast) was influencing academic outcomes (participation and engagement in school). Because of their high-profile successes, the BPP quickly became a target for the FBI, headed at the time by J. Edgar Hoover, who created the COINTELPRO program to infiltrate, surveil, and divide members to bring down and dismantle domestic organizations that challenged the status quo, including the Black Panther Party. An image showing the targeting of Black Panther Party leaders is included in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Asian American Movement, 1960s - 1970s

In the wake of the Civil Rights Movement and Black Power, Asian Americans were inspired to forge their own way based on a pan-ethnic identity. Rejecting the label, “Oriental,” young Asian Americans of the 1960s adopted the term “Asian American” to describe their identity and movement. Resisting both the “model minority” and “yellow peril” stereotypes, they organized for economic and racial justice in education, labor, and housing, along with fighting in solidarity with Black, Brown, and Native communities who faced related oppressions rooted in white supremacy, capitalism, and imperialism.

Asian American Studies historian, Daryl Maeda, pointed out how the Asian American movement “drew heavily from the African-American movement” in order to inform Asian American subjectivity and racial commonality, such as embracing the militant style of dress, adoption of the “Black Power” slogan to “Yellow Power,” and deeper connections between the Asian American and African American movements. For instance, the work of Japanese American activist Yuri Kochiyama’s dedication to Back liberation struggles and close friendship with Malcolm X (Fujino, 2005) (Dhingra and Rodriguez, 2021, p. 73).

Asian American activists and organizations participated in “serve-the-people” programs fighting for affordable housing, access to healthcare and social services, labor rights, women’s rights, and LGBTQ rights. For example, one of the major campaigns for housing was the decades-long effort to save the International Hotel (I-Hotel) in San Francisco, which primarily housed elderly Filipinx and Chinese men who lived in the single room occupancy building. When in 1969, the owners of the I-Hotel attempted to evict residents who had nowhere else to go, the Asian American movement rallied to protect the residents, even forming barricades and facing 250 riot police (Lee, 2015, p. 307 - 308).

Similar to what many other women of color activists faced in that era, Asian American women called out the sexism and secondary status they faced, being relegated to background work like taking notes, making coffee, and even cleaning toilets. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Asian Americans felt marginalized both within the mainstream white gay liberation movement and within the Asian American movement. Activist and journalist, Helen Zia remembered being put on trial by other Asian American and Black liberation activists in Boston, stating, “I had not yet come out, and they made it clear that if I did, I would also be out of the liberation community. That threatening message kept me in the closet for the next several years” (pp. 309 - 310).

The Asian American movement was uniquely transnational as well, as members organized against U.S. wars, militarism, and imperialism in Asia. For example, they protested against the Vietnam War, critiqued US military occupation in Okinawa and Korea, and aligned with other anti-colonial, anti-imperial, socialist, and communist struggles in Asia. As noted by Maeda, the Asian American movement “sought to achieve radical social change by building interracial coalitions and transnational solidarities” with the goal of dismantling interlocking systems of oppression (p. 304, p. 308).

The Asian American movement was formed across college campuses, including the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA) started by Yuji Ichioka and Emma Gee in 1968 at UC Berkeley. They were the first organization to use the term “Asian American.” AAPA was intentionally pan-ethnic, bringing together Asian Americans across generations, class, and ethnicity. AAPA also “explicitly critiqued the United States as a racist, imperialistic, and exploitative society,” pointing out how Asian Americans have been systematically affected by racial injustice. AAPA also committed to interracial solidarity with other “Third World people,” both abroad and within the United States. AAPA played a major role at both SF state (1968) and UC Berkeley’s (1969) Third World Liberation Front (TWLF) strike to bring about Ethnic Studies at colleges and universities across the nation (pp. 304 - 305).

Young Lords (1968 - 1972)

The Young Lords started in 1968 with Puerto Rican youth in Chicago, many of whom were former gang members. The socialist organization advocated for grassroots services controlled by and for the people. They also organized for Puerto Rican independence (a U.S. territory since the 1898 Spanish-American War), including leading a march of 10,000 in 1970 in New York City. The Young Lords Organization (YLO) chapter in New York City, founded by Puerto Rican college students, became the Young Lords Party. Chapters were formed mostly o the east coast and also briefly in Hayward, California (Ruíz and Sánchez, Korrol, 2006, pp. 815 - 816). The Young Lords were inspired by global liberation struggles and the Black Panther Party (BPP). The original Chicago group gained a national spotlight when taking over a local church to provide community services for the poor. Similar to the Black Panthers, the Young Lords dressed in military style with army jackets, combat boots, and purple berets with a YLO button (Hulst, 2013, pp. 636-639).

The Young Lords’ community organizing centered on the social needs of working class and poor Puerto Rican communities, including garbage collecting, free hot breakfast for children, clothing drives, child-care services, Puerto Rican history classes, health programs, and entertainment through poetry readings, music, etc. Their health offensive focused on taking over the Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx and organizing a lead poison and tuberculosis testing site. Another offensive focused on prison conditions for incarcerated Puerto Rican and African Americans, who were reporting high suicide rates, in addition to addressing police violence, drug addiction, and the war in Vietnam (Ruíz and Sánchez Korrol, 2006, p. 816).

Puerto Rican women were active in the Young Lords from the beginning, confronting “male chauvinism” within the party. In 1971, Denise Oliver, the first woman on the Central Committee, called for women’s participation, stating,

when the Party got started, there were very few sisters….We saw that we really weren’t gonna be able to do any kind of constructive organizing in the community without sisters actively involved…because most of the people that we’re organizing are women with children, through the free-breakfast program and through the free-clothing drive and health care programs (Ruíz and Sánchez Korrol, 2006, p. 816).

Women in the party called out how they were often relegated to domestic and office work, such as typing, taking care of children, and being sexualized by male members. Female Young Lords formed a women’s caucus, recognizing the need to discuss and dismantle machismo culture in the community. The party recognized the intersection of women’s oppression, capitalism, and imperialism, and eventually revised their Thirteen Point Program to assert gender equality and an end to homophobia (Ruíz and Sánchez Korrol, 2006, p. 816). The program also addressed the group’s desire for self-determination, anti-racism, community control over institutions like hospitals, schools, and law enforcement, for Puerto Rican history and Spanish language to be taught, and they demanded a socialist and nonviolent state (Hulst, 2013, pp. 636-639).

The Young Lords didn’t last a very long time, but they still made an impact by asserting Puerto Rican independence and rights for Puerto Ricans in the U.S. They experienced some divisions within the organization as well as infiltration by the FBI’s COINTELPRO, similar to what happened to the BPP. In 1972, the remaining Young Lords became the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization (Hulst, 2013 & Ruíz and Sánchez Korrol, 2006). Former members continued the fight for Puerto Rican freedom, by occupying the Statue of Liberty in 1977, demanding the release of Puerto Rican political prisoners and protesting against U.S. military exercises on the island of Vieques (Hulst, 2013, pp. 636-639).

Brown Berets

In the 1960s, heightened awareness of racial injustice inspired many groups to stand up and take action. The Brown Berets were one such group that formed among Chicana/o/x activists. It began with a group of high school students who were part of a civic participation program inspired by the Black Panther Party to take a stance of radical nationalism. Chapters formed in California and around the country, and many are still active today. The group shared ideological positions with the Black Panther Party, including resistance to police brutality, opposition to the Vietnam War, and a militant commitment to revolutionary social change. This position also made them a regular target for government interference and sabotage. They implemented free medical and food programs to help community members affected by disparities in access. The Brown Berets have always taken on a coalitional standpoint and embraced a commitment to Third World alliances with other communities of color in the U.S. and around the world. The image shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) features a young activist in 1994 as part of the Brown Berets preparing to participate in a protest for immigration equity and against Proposition 187.

American Indian Movement

During the 1960s, Native American communities were dealing with many of the same issues as communities of color in the United States. The US government embraced an urban relocation model that forced Native Americans off of reservations and traditional lands into low-income jobs and neighborhoods in cities and urban areas. Although the government promised jobs, housing, and healthcare, these were few and far between. The mixture of many tribal groups in large cities led to the embracing of a pan-Indian identity united by shared experiences of settler-colonialism, genocide, and displacement. This included dealing with tensions between urban Native communities and those living on reservations, the highest unemployment rates of any racial or ethnic group, and disparate rates of child abductions and children being taken into foster care and adopted by non-Native families. The pan-Indian community acted as a support system and buffer against racism and poverty and fostered resilience. Today, there is a backlash against the pan-Indian identity because it erases cultural specificity and traditional tribal knowledge.

The American Indian Movement (AIM) was first formed in Minneapolis in 1968 before expanding to other chapters around the country. Some of the key figures in AIM include Russel Means, Dennis Banks, Clyde Bellecourt, John Trudell, Leonard Peltier, and Mary Jane Wilson. Roberta Downwind suggested the name “AIM,” which lends itself to graphic interpretation in the form of arrows and targets, signaling the legacy and importance of resistance. One major difference between AIM and other civil rights movements was that their focus was less on integration with dominant society and more on maintaining cultural integrity, the enforcement of treaty rights, and empowering tribal sovereignty. Key issues for AIM included: economic independence and opportunity, police brutality and abuse, and culturally relevant healthcare. Women leaders played a key role in speaking up to both anti-Native issues but also the unique experiences and perspectives of Native feminists. AIM was involved in many demonstrations, including the occupation of Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay from 1969-1971, as well as the Longest Walk from Alcatraz to Washington, DC.

One major success of AIM was lifting the ban on Native American spiritual ceremonies that was established by U.S. law in 1884 through the American Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1978. This built on a decade of legal reform, including the 1965 Indian Self-Determination and Education Act, 1968 Indian Civil Rights Act, 1972 Indian Education Act, 1975 Indian Education Assistance and Self-Determination Act, and 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act. Like the Black Panthers and Brown Berets, AIM was targeted by the FBI for infiltration and disruption, and the national organization disbanded in 1978, although it was outlived by local chapters of AIM that continue to mobilize and inspire Native American and Indigenous activists today.

AIM was not the only organization to mobilize Native peoples from multiple tribes. For example, the National Congress of American Indians was founded in 1944 to face off against the federal government and improve the conditions of Native Americans. The group was somewhat more moderate in advocating for reforms. The National Indian Youth Council was formed in 1961 to advocate for sovereignty and human rights. Youth were dissatisfied with the advocacy and leadership of elders. Similarly, Women of All Red Nations (WARN) formed out of AIM and focused on the leadership and experiences of Native women.

Women advocates were key to many aspects of Native American and American Indian movements. For example, the occupation of Wounded Knee was a protest designed, organized, and implemented by older women. After spearheading dissent at Pine Ridge, the Oglala Lakota Sioux women took on more responsibilities, including carrying weapons. Leaders like Bisonette and Moves Camp were key elders who carried out negotiations on behalf of the movement. See also "Alcatraz, AIM and Wounded Knee" under Chapter 4.

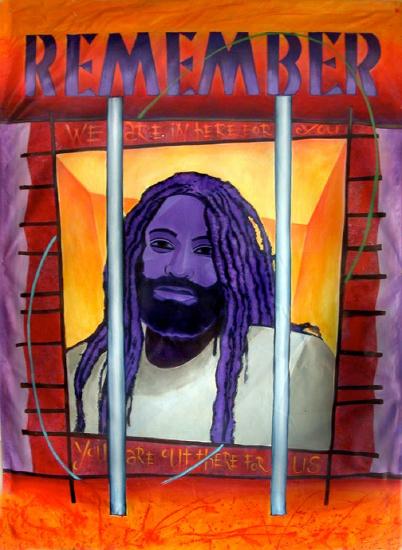

Sidebar: Political Prisoners

As part of the strategy of intimidation and subversion, the U.S. federal government has taken activists as political prisoners. Mumia Abu-Jamal was 14 years old when we has beaten by white racists and a police officer. He found the Black Panther Party (BPP) and embraced its approach to change, moving to Oakland to live with BPP members and organize for the movement. However, he also came under surveillance by the FBI, which made him a target. He was charged and convicted with killing a police officer and has been held in prison ever since, currently serving a life sentence without parole. Similarly, Leonad Peltier was arrested shortly after his involvement in the Wounded Knee occupation and general community leadership. He was charged for the death of two police officers, although there is much evidence that was missing from the trial. Peltier maintains his innocence and substantial evidence was not reviewed in the first trial and appeal for the case. However, the targeting of activists for their outspoken advocacy can lead to a “chilling effect” where activists are less likely to take risks out of fear of imprisonment or other consequences. You can view artistic renditions of both individuals in Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\) and Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\).