11.4: Labor Movements- Domestic Workers

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 143355

- Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick & Kay Fischer

Worker-led Struggles

Institutionalized rejection of difference is an absolute necessity in a profit economy which needs outsiders as surplus people.

- Audre Lorde, 1998

Although many workers in the U.S. today might take for granted the 8-hour work day, the end of child labor and slave labor, minimum wage, and more, these basic workers’ rights weren’t simply handed down from our government, "generous" companies, nor bosses. These were hard-won rights that took decades and unfortunately many lives. Even when workers’ rights were won, they weren’t always equally applied, such as when the National Labor Relations Act was passed in 1935, and African Americans and other workers of color were largely excluded from such legislative protections until decades later. Lately however, even those important wins stemming from our rich and violent history of labor struggles have been taken away due various structural changes, including the rise of mega-corporations, the consolidation of wealth, deindustrialization, and the continued hyper-exploitation of contract, part-time, undocumented, immigrant, and female workers.

Along with the capitalist exploitation of the masses (intersecting with white supremacy and colonialism), there are worker-led struggles whose legacies have most definitely made an impact and continue to influence current workers’ movements. In this section, we’ll examine the domestic workers labor struggle through an Ethnic Studies lens. In the next section, agricultural workers.

Domestic Workers

Paramount to understanding the significance of labor movements, we should start by examining the experiences and movements of the most exploited workers, who often end up being women of color, including colonized women, enslaved women, and immigrant women of color.

In this section, we’ll examine the political impact made by domestic workers movements. As pointed out by Premilla Nadasen in her book, Household Workers Unite (2015), social movements and activism by domestic and household workers are often ignored in the media, overshadowed by narratives of helplessness and domestic workers needing rescue. Contrary to popular discourse, women of color domestic workers have resisted oppression for hundreds of years, from colonization to slavery to modern-day systemic racism, patriarchy, and capitalism. Through it all, they have attained political power, commanded respect in their work, and continue to make significant legislative, economic, and social transformations for domestic workers.

Sidebar: "A History of Domestic Work and Worker Organizing" Timeline

Take a look at the "A History of Domestic Work and Worker Organizing" digital timeline by the National Domestic Workers Alliance and activist-scholars Jennifer Guglielmo, Michelle Joffroy, and Diana Sierra Becerra. Using vibrant images and informative text, the timeline offers an in-depth examination of the rich history of domestic workers "resilience and resistance."

Enslaved Indigenous and African American Domestic Workers

We start with the impact of European colonization on indigenous populations of the Americas and the congruent enslavement of people from Africa. Although approaching the first Europeans with generosity and peace, Indigenous peoples were met with perverse violence and cruelty, their estimated population of 100 million slashed severely by 95% within the first 200 hundred years of colonization. By the 1600s, the Spanish were prominent settler-colonists of the Americas and had coerced, often violently, both Indigenous and African populations into a permanent servant status. This included unpaid domestic labor at Catholic missions, where Indigenous women were abused. They resisted in both covert methods, such as slowing down work, or more openly by leading revolts and setting missions on fire. One such resistor was Toypurina, a Gabrielino Tongva medicine woman, who led an armed rebellion against the San Gabriel Mission in 1785 (Domestic Workers Make History, 2022, 03:02).

Amongst early New England settler-colonists, the developing society began to rely on enslaved African labor by the mid-18th century. Tera W. Hunter, professor of American History and African American Studies, noted that enslaved Black women were creative in “seiz[ing] time…which they weren’t given” (Domestic Workers Make History, 2022, 03:59). This included passing around abolitionist newspapers in secret, joining rebellions, going on strikes, or running away from slave-owners. One of the most well known household names for abolitionists was Harriet Tubman, who was also a former domestic worker. Famous for leading some 13 expeditions to free others from slavery, Tubman also led African American union soldiers to free over 700 enslaved people in South Carolina in 1863 (04:45).

Legacy of Slavery Among Domestic Work in the South

Despite slavery being abolished through the 13th amendment, Black domestic workers continued to labor in slave-like conditions. Although technically free people, the legacy of slavery remained steadfast (Domestic Workers Make History, 2022, 05:47). Black domestic workers organized for better pay and set parameters around their labor, such as insisting that if they were hired to be a cook, they should not have to clean the house or become a child nurse. They created mutual aid groups and pooled their resources so that they could support one another economically during times of need.

In 1881, the largest domestic workers strike of the 19th century took place in Atlanta, Georgia, where a group of 20 Black washerwomen collectively decided on a standard rate for their work. They named themselves the Washing Society and within three short weeks, they had already recruited 3,000 members (including Black cooks and housekeepers, and Irish immigrants). They threatened to go on a general strike and were met with arrests and fines as retaliation. Regardless, the movement spread and washerwomen struck across various states. In North Carolina, strikers declared: “Let the white people learn to serve themselves” (Domestic Workers Make History, 2022, 09:30).

By the 1930s when the Great Depression hit, workers and unemployed people demonstrated on the streets, demanding labor protections, soon compelling the federal government to pass some of the first labor protection laws. Professor Nadasen stated how 8 hour days and overtime pay were all a part of labor laws “that established a broad safety net for workers across the country.” Yet two categories of workers were excluded from such legislation: agricultural and domestic workers, populations that disproportionately included African American and Latina women, “so racism played a big role in how labor protections were allocated in the 1930s” ((Domestic Workers Make History, 2022, 10:30).

Kidnapping Native American Children

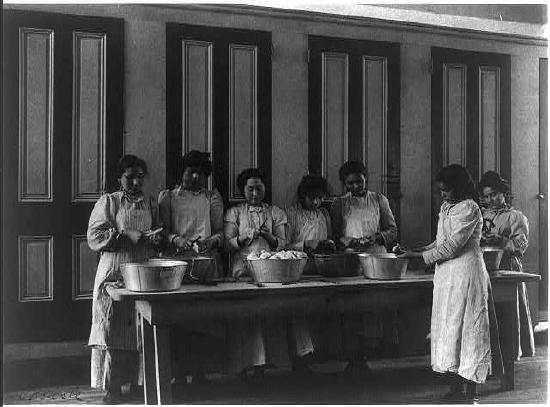

From the late 19th century into the mid-20th century, the practice of kidnapping Indigenous children from their families and imprisoning them at government sponsored, so-called Indian Boarding Schools was common practice. The motto “Kill the Indian, Save the Man” was used to justify the violent and abusive treatment endured by 20,000 Native children at these schools, with the purpose of destroying Indigenous cultures and families. Native girls were tracked to provide domestic work, trained to do ironing, cooking, and housekeeping. Brenda Child (Red Lake Ojibwe) wrote, “Indian students in the government boarding schools were constantly bombarded with the notion that they were best suited for menial labor” (Guglielmo, et al., 2021, “Menial Labor as Civilization”). Outing programs placed Native teen girls to be live-in domestic workers in white homes across the southwest in cities like Los Angeles, Tucson, and San Francisco. The practice of separating Native American children from their parents and families continued until 1978, when the Indian Child Welfare Act gave Native American parents the legal right to resist their child’s placement in Indian Boarding Schools. See also "Assimilation, Boarding Schools and Adoption" under Chapter 4.

Domestic Work in the Borderlands

Indigenous and Mexican women of the borderlands had been resisting slavery, kidnappings, and deplorable working conditions as domestic workers for over 100 years. Workers fought back in various ways, from work stoppages to leaving ranchos, to violent insurrections like the one at Rancho Jamul near San Diego, California in 1837 (Guglielmo, et al., 2021, “The Rancho Jamul Raid”). After U.S. conquest (1848) led to a remapping of borders, Indigenous populations faced land-theft, removal, containment, and surveillance. Chicanx people now on U.S. territory lost property as well, being “relegated to low-paid, low-status work, such as domestic and agricultural labor” (“We Didn’t Cross the Border, the Border Crossed Us”).

Mexican domestic workers were paid a third of what white domestic workers (largely European immigrants) were paid for the same work. In 1933, Chicana domestic workers established the Asociación de Trabajadoras Domésticas (The Association of Domestic Workers), organizing 700 domestic workers to demand higher wages. By the 1930s, almost all domestic workers were Mexican women from El Paso, Texas or Ciudad Juarez, just south of the border in Mexico. Employers in Texas would pit domestic workers from El Paso and Juarez against one another through low wages (Guglielmo, et al., 2021, “On Strike in El Paso”). If a worker in El Paso wanted fair wages, the employer would simply hire women from Juarez and pay them even less.

Despite the perpetual threat of deportations looming over workers, domestic workers continued to organize. When the Asociación de Trabajadoras Domésticas organized a strike, employers tried to have one of the leaders deported, even though she was a U.S. citizen. But after other unions joined in support, the employers conceded and met the strikers’ demands, agreeing to pay domestic workers a dollar more per week.

Domestic Workers in the Civil Rights Movement

The modern Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. is recognized as having started with the arrest of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott. More than a half century later, much of the labor and leadership by African American women have been erased from historic accounts of this movement, including the role of Black domestic workers in bus boycotts. In fact, most bus riders in the South were Black domestic workers, and they were the ones to initiate bus boycotts to bring an end to racial segregation. Depending on public transportation to get to their place of employment, domestic workers faced abuse and patronizing treatment by drivers. If the women didn’t give up their seats for a white passenger, they risked getting kicked off the bus, arrested, hit, or even killed for their resistance, as some drivers carried weapons (Guglielmo, et al., 2021, “The Struggle Against Everyday Violence”).

Georgia Gilmore, a cook and maid, had stopped riding the bus in protest of her mistreatment, years before Rosa Park’s famous arrest. Of the boycott, Georgia said,

This new generation had decided that they just had taken as much as they could….After the maids and the cooks stopped riding the bus, well, the bus didn’t have any need to run. And so instead of riding the bus, they would walk. And then they began to form a carpool (Domestic Workers Make History, 2022, 16:16).

Domestic workers organized their friends to join the boycott, passed out flyers, and fundraised by selling pies and other meals, leading to a successful boycott of over a year when on November 13, 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s ruling that segregation on buses violated the Fourteenth Amendment. According to Professor Nadasen,

The Montgomery Bus Boycott was the moment that signifies the ways in which domestic workers were really the leaders of the boycott. And without their support, without their involvement, the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and much of the Civil Rights Movement would not have been possible (2022, 17:25).

The Rise of Workers Centers and Domestic Worker Organizing Today

Also during the 1970s and '80s, African American women began shifting out of domestic labor, as job markets started to slowly open up due to reforms that came out of the Civil Rights Movement. In the aftermath of U.S. wars, occupations, changing immigration laws, and interventions in Asia and Latin America, millions were uprooted from their homes resulting in migrations to the United States (Domestic Workers Make History, 2022, 28:05). With limited access to citizenship, women of the Caribbean, the Philippines, Mexico, and Central America were starting to find scarce opportunities for employment other than domestic work. Linda Burnham of the National Domestic Workers Alliance notes that because some of these women came as experienced organizers from their countries of origin, the domestic workers movement evolved to be primarily led by immigrant women. With this came workers centers - places that addressed “particularly high degrees of exploitation” that the largely undocumented immigrant labor force faced, such as wage theft and “absolutely no rights to the basics” (29:20).

Mujeres Unidas y Activas (MUA) was an early workers center, established in the Bay Area. One of their co-founders, Clara Luz Navarros, used to be a nurse and community leader in El Salvador, fled political persecution, and brought her skills to the San Francisco Bay Area (Domestic Workers Make History, 2022, 30:31). Still active today, MUA is a grassroots organization led by Latina immigrant women advocating for “personal transformation and building community power for social and economic justice” (Mujeres Unidas y Activas, “MUA mission”). MUA pushed for the California Domestic Worker Bill of Rights, which passed as state law in 2016, and continues to fight for sanctuary protections in Alameda County to advocate for women seeking asylum or facing deportation, including the right to asylum for domestic violence survivors.

Transnational Movement Building by Filipina/x Domestic Workers

In the case of the Philippines, their economy, labor, and education continue to be heavily tied to and influenced by U.S. colonialism and militarism. Asian American Studies professor, Dr. Robyn Rodriguez, argues that the Philippines has become a “labor brokerage” state that “actively mobilizes and facilitates the export of workers…because it benefits from remittances (money sent to the homeland from immigrants…working abroad)” and therefore commonly migrate to the U.S. as workers (Dhingra & Rodriguez, 2021, p. 196). Neoliberal policies that further impoverish so-called “third world” nations have made it difficult for ordinary Filipinx people to find jobs and care for their families in the Philippines, and therefore end up working in a foreign country as temporary migrant workers. This is such a phenomenon that an acronym was created: OFWs or Overseas Filipino Workers, who were at 1.77 million in 2020 (Republic of the Philippines Statistics Authority, 2021). Remittances sent from OFWs in Canada, the United States, Japan, and more are what many in the Philippines depend on for survival, and remittances sent from domestic workers abroad are the “third-largest source of tax revenue for the Philippine government” (Guglielmo, et al., 2021, “Exporting Domestic Workers for Profit”). Some are even trafficked into domestic work, tricked into false contracts, having their pay withheld, and must endure living in an abusive setting (Benitez, 2018).

The Damayan Migrant Workers Association in New York City organizes with low-wage migrant workers to end labor trafficking and demand worker rights. Lead organizer, Riya Oritz, who considers herself a product of forced migration and a child of one of Damayan’s co-founders, explained how being put in a desperate situation made thousands vulnerable to placement agencies that would often exploit and profit off OFWs. Ortiz’s mother, Linda Oalican, pointed out how the struggle for domestic workers rights is multifold: addressing immediate conditions for workers, but also addressing larger systems of exploitation, such as patriarchy, imperialism, neoliberalism, and white supremacy, that created oppressive conditions for domestic workers in the first place (Benitez, 2018).

Domestic Workers Bill of Rights

At the first U.S. Social Forum in Atlanta, Georgia in 2007, domestic workers across the country gathered and established the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA). Along with various organizations and workers centers, they helped to pass the first comprehensive domestic workers bill of rights in New York in 2010, and soon similar campaigns sprang up across the nation. Silvia Gonzalez of Casa Latina, Seattle, stated (translated from Spanish): “There is more power and we start winning more bills of rights in more places. It’s like popcorn when they start popping: we won one state, we won in another state” (Domestic Workers Make History, 2022, 35:05). In 2019, NDWA introduced the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights at the federal level. Central to NDWA’s organizing mission is “building a multi-racial alliance to address the impact of anti-Black racism, unjust immigration policies, and other systems of oppression” (35:26). Allison Julien, of We Dream in Black, NDWA-New York, stated that she’s “inspired by the domestic worker history. I’m inspired by their resilience, their ability to build community, their ability to build relationships in order to advocate for the change needed in the domestic work industry” (36:38).