6: Our Story - Latinx Americans

- Page ID

- 145368

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)At the end of the module, students will be able to:

- describe the process of exploration, contact, and colonization of Spanish explorers in the Americas.

- explain Manifest Destiny and the American acquisition of land through war and conflict.

- explore the role of Latinx peoples in America during WWII and after.

- describe the contributions of progress of Latinx Americans during the civil rights era

- explore the issues of the late 20th and early 21st century and how they have impacted Latinx Americans

KEY TERMS & CONCEPTS

|

Adams-Onis Treaty Bracero program California Gold Rush César Chávez Christopher Columbus Colonial Caste System Conquistadors Farmworkers Movement Hart-Cellar Act of 1965 Hernandez v. Texas Iberians League of United Latin American Citizens Manifest Destiny |

Mendez v. Westminster Mestizo Mexican American War Monroe Doctrine Mulatto Operation Wetback Pachuco movement Reconquista Roosevelt Corollary Spanish-American War Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Young Lords Zoot Suit Riots |

INTRODUCTION

Latinx Americans have one of the more complex histories of the development of the Americas. Through contact, colonialization, and further political and social dynamics, the Latinx population has grown into a sizable and influential part of the United States today.

Like other racial minorities, Latinx Americans have been exploited for their labor, discriminated by American society, and denied their civil rights despite their contributions to the nation. The Latinx identity is not considered a ‘race’ in America, but rather an ethnic distinction. Because of this ambiguous categorization, Latinx Americans have been misunderstood in political and social standards throughout history.

This is their story.

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES & COLONIZATION

In order to understand Latinx history, we have to begin with the indigenous peoples of the Americas, whose history is inextricably tied to Latinx history. As stated in Module 2, the peoples of the Americas traveled across the Bering Strait and migrated down the continents to lay their roots throughout the Americas. Over time, they constructed boats and continued to develop island civilizations in the Caribbean as well. The peoples of the Americas adapted and thrived in the environments where they settled, some creating vast and complex civilizations and even empires.

When Iberians, the Portuguese and Spanish Europeans that lived on the Iberian Peninsula, started to venture out into the open ocean, they would eventually make their way across the Atlantic. The Portuguese focused on the formation trading outposts rounding the gold coast, as well as the colonization of Africa’s western coastal islands, while the Spanish funded a monumental journey that made landfall in the Caribbean. This was the journey of Genoese born Christopher Columbus.

After Columbus’s contact with indigenous peoples, more and more explorers made their way across the Atlantic Ocean. Among those men were Hernan Cortez and Francisco Pizarro. Through the efforts of political maneuvering, brute warfare, and subsequent disease, Iberian conquistadors dominated the powerful empires of the Americas. These men were named for their participation in the Reconquista, or reconquest of Spain which was once ruled by Muslims during the middle ages. Cortez and Pizarro identified two goals: control the land and establish colonies for the benefit of the mother country and convert the natives to Christianity. The more souls they committed to Christianity, the more powerful they became over Muslims. With these goals in mind, the Americas were changed forever.

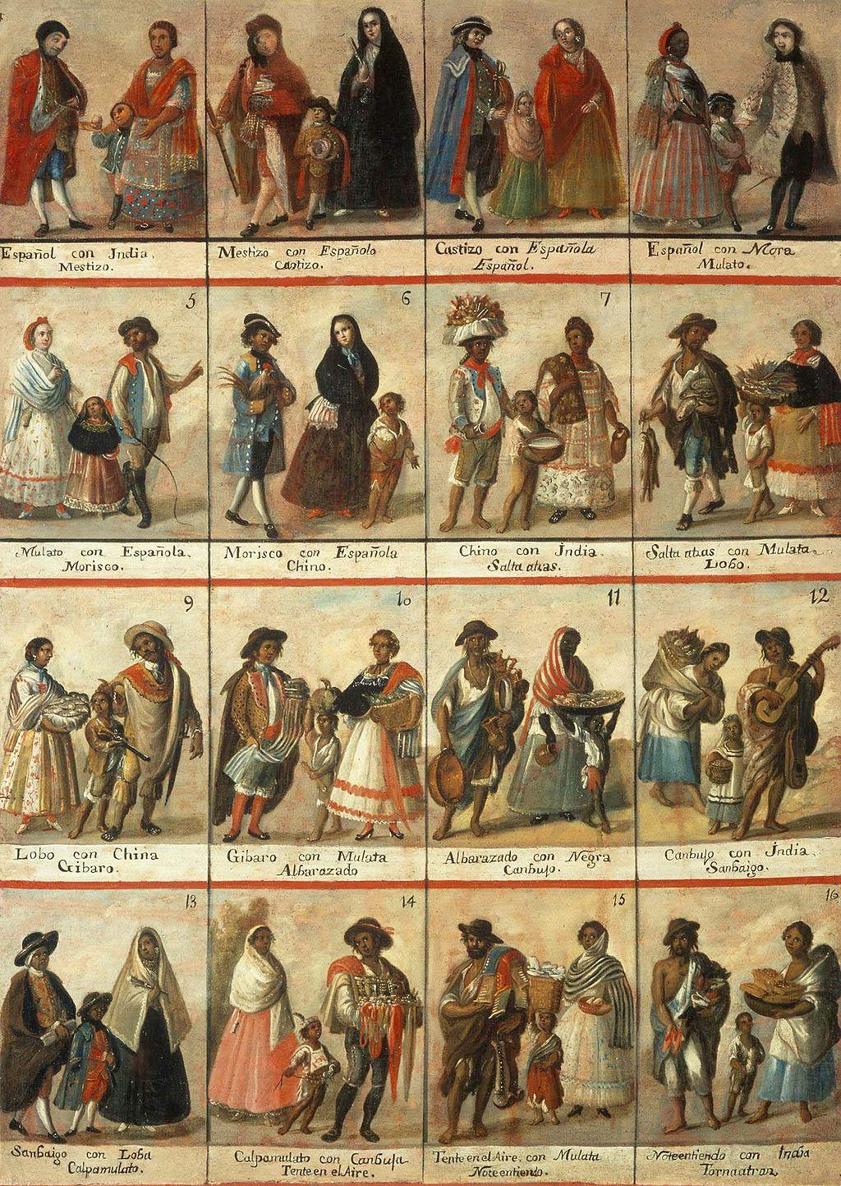

As Iberians took over the Americas, some sought alliances with powerful families of the remnants of the indigenous empires. These alliances were mostly forged through marriage. Society was further changed by the introduction of African servants and slaves. Over time, the intermarriage of peoples created a complex and vast Colonial Caste System, or Las castas, that gave privilege and preference to European blood and ‘white’ skin tone. Categories of Las castas included mulattos, offspring of a Spaniard and African, or mestizos, a child of a Spaniard and an indigenous person.

These definitions determined one’s social status and access to opportunities and resources or lack thereof. Like many other areas of the world, lighter skin tone was preferable and privileged, while darker skin tones meant inferiority and discrimination. As the years went on, the Latin American nations such as Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba were formed using these racial and ethnic distinctions.

Casta painting showing 16 racial groupings

18th century, Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Tepotzotlán, Mexico

WESTWARD EXPANSION & WARFARE

During the colonial development of the U.S., the Spanish continued to establish settlements throughout their territories in the Americas. In North America, of the areas that would eventually become the U.S., the Spanish controlled the west, southwest, and Florida, until about the early 19th century. Spanish speakers were, in fact, some of the earliest settlers of North America, and would remain strongly rooted in those regions throughout this nation’s history – and even today.

After the American Revolution and the founding of the nation, settlers looked to the west for more room to develop and grow. The land lust of the American settlers was felt by many groups, and among those groups perhaps the ones to have been affected most were Native Americans and Latinx populations. This land lust was justified in the notion of Manifest Destiny, a term covered in more detail in Module 2.

The control of lands from the Atlantic to the Pacific began first with Florida, which was acquired by John Quincy Adams through the Adams-Onis Treaty in 1819. The treaty was signed to settle a border dispute with Spain and an ongoing conflict with General Andrew Jackson and his invasion of Florida and attack on the Seminole Indians. This military action by Jackson was used as leverage over the Spanish to demand Minister Onis to control the inhabitants of Florida or cede the region to the United States. The Seminole tribe was considered disruptive to U.S. interests because they had a history of harboring fugitive slaves. As discussed in Module 3, enslaved African Americans were considered property of Americans, and therefore the Seminoles were in possession of stolen property. The treaty settled differences between the nations by Spain ceding control of all of Florida and the Pacific Northwest, while the U.S. recognized Spanish control over the region later known as Texas, clarifying the borders between New Spain and the United States.

Americans soon after reneged on their promise to respect their western boundaries. By the 1820s, American farmers of the south had continued to press into western regions, growing and expanding their wealth despite what sovereign nation controlled the land. The year of 1821 was a victorious one for Mexico, for it gained its independence from their Spanish colonial masters much like Americans did in 1783. However, in forming their new nation, the Mexican government worried about their northern territories and the American influence that resided in them. The fledgling nation tightened its grip on their nation by instituting laws that would weaken the American investment farmers in the north. This legislation included the building of military forts, increasing taxes on foreigners, the abolition of slavery in 1829, and the barring of immigration across the northern border in 1830. All these actions were meant to weaken and dismantle the American influence in northern Mexico, but instead the Americans pushed back.

The path the Americans chose was in line with Manifest Destiny and the American ethos of resistance. Instead of complying with the Mexican government, Americans allied with the remnants of Spanish elites and waged a revolution against Mexico. The Texas Revolution lasted several months, and in the end, Texas gained its independence from Mexico and operated as its own independent nation from 1836 until the U.S. annexed the region in 1845. The Americans continued to till their lands with the use of slave labor as an independent territory and into 1860.

After Texas entered the Union, President James K. Polk set his sights towards the west, again in line with the concept of Manifest Destiny. In November of 1845, a diplomat was sent to Mexico to offer to buy the western territories from Mexico, and the offer was denied. But the U.S. government was relentless, and instead of cutting their losses, they claimed a border dispute to settle the matters with war. President Polk stationed a military force of 4,000 men at the disputed border line, and the Mexican government responded with its own military force. When tensions erupted and shots were fired, Americans were killed. Polk used this opportunity to declare war on Mexico, and Congress granted his request. The Mexican American war had begun.

The Mexican American War was a very short-lived war, officially beginning in the fall of 1846 and only lasting about four months. The Americans had the advantage of attacking from both land and sea and quickly came to occupy the capital city of Mexico. During this occupation of Mexico City, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed. This treaty ceded about half of Mexico territory to the U.S.; territory that would eventually become California, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, Colorado, and Wyoming. This vast acquisition of land would have thousands of Mexicans faced a choice of leaving their land and homes to move within the new borders of their nation or remaining where they were to become Americans. Approximately 30,000 Mexicans would stay and represent the bulk of Latinx Americans for many years, all having to adapt and mold into American society as many more would do in the years thereafter. In their efforts to adapt and assimilate into American society, they would find themselves faced with harsh discrimination, particularly in politically charged territory like California.

After the acquisition of land from Mexico, Americans had fulfilled their goal of Manifest Destiny – they now controlled North America from the Atlantic to Pacific coasts. The consequences of achieving that goal were high, for civil war was brewing. One event that accelerated the coming war came with the process of settlement of new territories, namely the state that would become California. When the precious metal known as gold was discovered in California, a rush of eager migrants flooded into the territory during the California Gold Rush to extract the wealth that the land had to offer. As countless migrants descended on the land, a certain lawlessness was experienced by those settlers, provoking a need for structure, government, and order. Lawmakers identified a need for order and rushed into annexation and statehood. However, the delicate balance of free and slave states needed to be maintained, so a political compromise settled matters, formally called the Compromise of 1850. This negotiation contained several different concessions to satisfy differing political interests, including California accepted as a free state into the Union.

During the Gold Rush beginning in 1848, and the establishment of a California state government, most non-White residents were given little consideration and rights. Generally, white California residents treated once Mexican citizens with disdain as they would treat most racially minoritized groups in California like the Chinese and the Native Americans.

As the American Civil War raged on through the 1860s, many of society’s issues were put on hold, including Latinx American labor issues and gold rush conflicts in California. From the time of land acquisition to the 20th century, the southern border remained relatively open, and migrants openly crossed to look for work when needed. Spanish speakers from Latin America were welcomed with the same xenophobia as many other migrants of the late 19th century, but many only stayed for temporarily for work, and returned home.

After the War of 1812, the U.S. had beaten the British a second time, and established itself as a fully formed nation on a global stage. Just a few years after, James Monroe issued the Monroe Doctrine, a U.S. policy that took a stand against any attempts at European colonialism in the Americas – North, Central, or South. Later, Theodore Roosevelt upheld this same policy, and reiterated the U.S. strongarm on the Western Hemisphere and the defense of any Latin American country. This policy was called the Roosevelt Corollary; and using this policy, the U.S. government intervened in many foreign affairs in countries like Venezuela, Panama, and Cuba.

Under the guise of these policies, the U.S. intervened in various political conflicts throughout Latin America in the 19th and 20th centuries. As some of these Latin American regions attempted to assert their independence from their colonial oppressors, regions like Cuba found support from their American counterparts. The Cuban Liberation Movement in Cuba was supported by a newly formed Cuban Solidarity Movement in the U.S. This movement identified the themes of liberation in Cuba similar to the abolition of slavery. (Ortiz 2018). Through their efforts, the plight of Cubans gained more awareness in America, leading to U.S. intervention in 1898.

The Spanish-American War of 1898 found the U.S. involved in an armed conflict that eventually helped Cuba gain its independence from Spain. This was a short-fought conflict that ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris, wherein Spain ceded control of several territories including Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. To this day, Guam and Puerto Rico are unincorporated territories of the U.S., meaning residents of the countries are American citizens but do not pay federal taxes or have voting representatives in Congress.

By the 1910s, Mexico was suffering national strife during the Mexican Revolution. This conflict brought many Mexican nationals across the border looking for safety and opportunity, much like other migrants in the previous decades. This was an unwelcome shift for Americans that were used to temporary migrant laborers of the past. These settlers looking for permanent residences were met with harsh xenophobia. Many of the new migrants settled down in the southwest and California to work in expanding agricultural territories of Arizona, California, and Texas. This huge influx of migrants spawned a need for border control, which began in 1924.

As a counterweight to the racial discrimination of the 1920s, an organization was founded to defend Latinx peoples from institutional discrimination. LULAC, or the League of United Latin American Citizens, was formed in Texas and sought to end discrimination against Latinx Americans. In a LULAC newsletter, the writer blamed “ignorance” for the treatment of Latinx communities. For example, one of their earliest high-profile cases was to sue a school district in 1930 for segregation of Mexican children; however, the case did not rule in their favor. This case would serve as an important steppingstone for a similar lawsuit in the 1950s.

LABOR & CIVIL RIGHTS

World War II opened new avenues of opportunity for ethnic minoritized groups like Latinx Americans. Approximately 400,000 to 500,000 Hispanic and Latinx Americans fought in the war. This number varies by the source because of misrepresentation or underrepresentation of groups like Afro-Latinos. Like most veterans that are people of color, they were treated badly upon return. Many were not allowed the benefits of the GI Bill, and others returned to hometowns that enforced segregation, despite service to their country.

Like many minoritized groups during this era, like women and Blacks, Hispanics and Latinx Americans found new employment opportunities due to shifts in the workforce. Better paying factory jobs drove many racial minorities into cities. Some gained employment in industrialized jobs making uniforms, bullets, planes, etc.

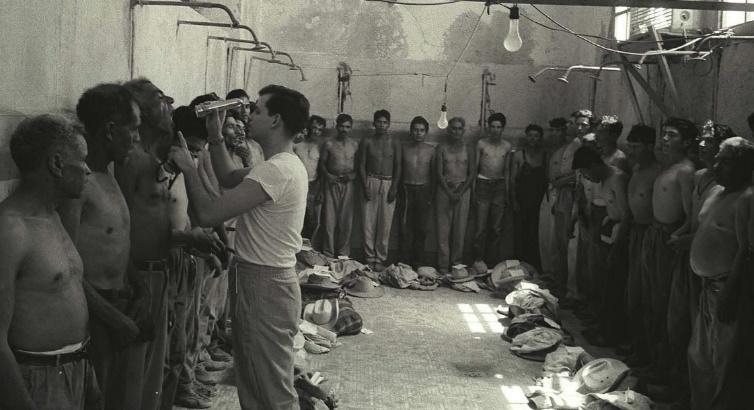

The shifts in the labor force also created a desperate need for agricultural workers. In solidarity during wartime, the U.S. government and the Mexican government signed a deal called the Bracero program. The program was used to bring Mexican agricultural laborers into the U.S. for work while guaranteeing them fair wages, adequate shelter, and food. This initial agreement was meant for wartime but was extended until 1964. The agreement sounded great on paper, but in practice had many issues. There were many accounts of “adequate” living conditions that were substandard at best, and numerous accounts of racial discrimination. Wage discrepancies, withheld pay, or inconsistent pay were common among Bracero workers. The workers had no say in the negotiations of labor contracts and were virtually powerless in the process from the beginning. Furthermore, even though the program was extended several years, Bracero workers were never given a pathway to citizenship. The whole program was inconsistent, unfair, and at times outright abusive. In 1954, after the director of the INS became alarmed by the presence of Mexican laborers in southern California, he initiated “Operation Wetback,” a program to deport illegal immigrants to Mexico. This initiative ignored the fact that many of these farmworkers came legally under the Bracero program, and some of those deported were American citizens.

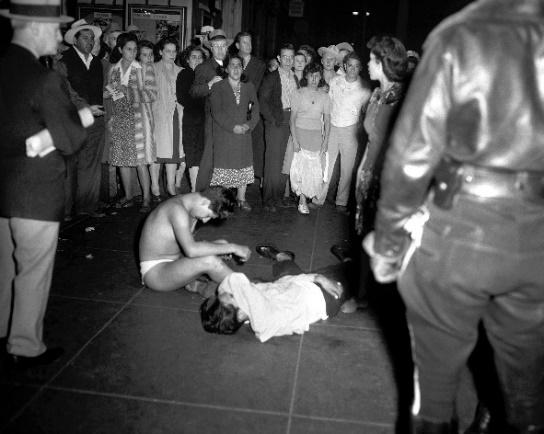

Meanwhile, as the Bracero workers were being mistreated in the west and southwest, Los Angles found itself in an incident of racial conflict during the Zoot Suit Riots. WWII was a global conflict that had vast effects on the home front in America, including stoking racial tensions in areas like southern California. Discrimination against Latinx communities is a concept that was common in the region even before it was a state. This all came to a head because of rationing during the war.

A Zoot Suit was a type of suit that was popularized during the Harlem Renaissance. The suit included an oversized jacket with coat tails, large voluminous pants with pegged ankles, sometimes a watch chain and two-toned shoes. This look was later co-opted by the Mexican youth of the Los Angeles area. This youth culture was called the Pachuco movement.

Both young men and women participated. However, to wear a zoot suit during war time and rationing was frowned upon because of its excessive fabric; and this, coupled with rising racial tensions in the area soon erupted into violence. Although many Pachucos wearing zoot suits did not fabricate or purchase them during wartime, thereby violating rationing laws, they were still targeted as being unpatriotic and un-American.

The origin of the riots is hard to pinpoint, but the initial act was connected to some young Pachucos and navy servicemen in Los Angles. Because the city had a military base nearby, there were often military servicemen present. The initial altercation sparked a reaction of vengeance by those in the area, and havoc was set upon anyone in a zoot suit or who appeared to be part of this Pachuco culture.

Men, many of them enlisted men, packed into cars to descend upon the Latinx barrios of Los Angles to hunt down Zoot Suiters. The attackers used bats, chains, and other weapons to assail these young Pachucos. When the police were called, the ones put in jail were often the victims of the violence, the young Latinx men. The attacks lasted for six days in the summer of 1943, and would be repeated in several other major cities, each targeting Latinx youth.

After the conflicts of the WWII era, Latinx Americans, like other racial minorities questioned their value in American society. Cold War political policies sought to defend peoples abroad, but many minorities were unable to access civil rights at home. The first significant target of racial discrimination was the education system. Before the Brown v. Board decision, there was another case that challenged segregation in schools, and this was the case of Sylvia Mendez.

Mendez v. Westminster (1947)

In 1947, the case of Mendez v. Westminster, a class action lawsuit was brought against the city of Orange County, California for the practice of “Mexican schools.” In the city of Westminster, schools were established for children of Mexican descent because they were deemed as “special needs” since they were Spanish speakers. This case was tried in the U.S. Supreme court, and the practice of “Mexican schools” was deemed unconstitutional, for it was proven to instill a sense of inferiority amongst Mexican children forced to attend these schools. This case would pave the way for the monumental Brown v. Board decision that upended the separate but equal clause based on similar findings.

Hernandez v. Texas (1954)

Later, another monumental case was decided in the U.S. Supreme Court to bring clarity to the racial definition of Latinx Americans. The case of Hernandez v. Texas was litigated in 1954 by the first Mexican American lawyers to stand before the U.S. Supreme Court. Peter Hernandez was a man who was convicted of murdering another man in a fatal shooting outside a bar in Texas. The legal case was not to dispute the conviction but rather the subject of discrimination because Hernandez was denied a fair jury of his peers. Historically, Mexicans were systematically excluded from jury duty due to discrimination. However, defenders of the practice would argue that since Latinx Americans are racially categorized as ‘White’; therefore the defense claimed Hernandez was in fact fairly represented. In the end, the court ruled in favor of Hernandez because they proved that there had never been a member of a Texas jury that had a Spanish surname. The ruling found that this type of discrimination was unconstitutional.

Both of these cases found that even though the law distinguished Latinx Americans under the racial category of White, overt racial discrimination occurred based on national origin or ethnicity. These cases determined that the Latinx community was afforded protections under Constitutional law. Although these cases sought to protect Latinx Americans, the end of segregation and discrimination was a work in progress.

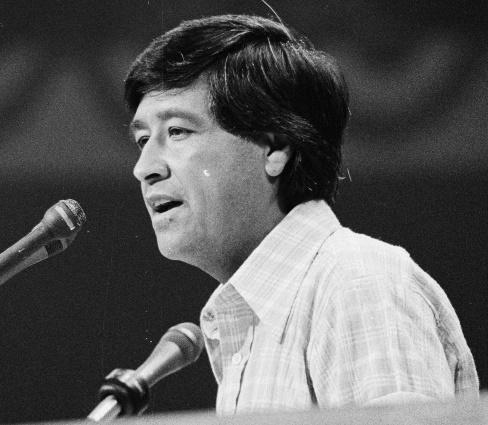

On the front of labor issues in the U.S., many issues needed to be addressed. The abuses of the Bracero program continued to impact Latinx communities, especially after the initiation of Operation Wetback and the deportation of many farm laborers. The work of the Farmworkers Movement grew out of the valleys of California. The famous César Chávez, a WWII veteran, rose to prominence as an activist and organizer of the National Farm Workers Association, alongside Dolores Huerta and Gilbert Padilla. This group combined forces with Philip Vera Cruz and the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee to protest the unfair labor practices of California grape growers. Their primary tactic was a consumer boycott - to refrain from buying and consuming any products that were derived from these grape farmers. Other forms of protest by the organizers included marches and Chávez’s fasting. The most notable march was led by Chávez in 1966, extending 300 miles from Delano, California to the state capital of Sacramento. In the end, labor contracts were negotiated between the growers and the farmworkers unions to increase wages and improve working conditions such as limiting the use of harmful pesticides (Ortiz, 2018).

Latinx Americans continued to participate in the civil rights movements of the 1960s in Chicago in the name of the Young Lords. This movement was led by young Puerto Ricans but also involved the participation of other Latinx groups. Their organizing focused on education and community building. The Young Lords provoked the formation of other chapters active in New York City and other areas of the eastern seaboard. In NYC, the Young Lords sought to fight inequities of the conditions of minority neighborhoods in regard to infrastructure and access to government programs.

Like other civil rights movements of the late 1960s, the Brown Power, or Chicano/a movement in Southern California demanded recognition and the end of racial discrimination in the U.S. This was an extension of the farm workers movement in the California Central Valley. Additionally, the Hart-Cellar Act of 1965 opened immigration to other Latin American countries, continuing the trend of diversification of American society. Along with other racial and ethnic minorities, Latinx communities struggled with identity, discrimination, and injustice into the end of the 20th century. Despite these struggles, many achieved progress in education, gainful employment, and political representation.

THE RECENT PAST

After the tumultuous era of the 60s and 70s, Latinx Americans continued to diversify American society. However, because of racial categorization, some Latinx Americans struggled with identity. According to the last 20 years of census data, millions of Latinx Americans chose “other” as their racial category on the census. Legal precedent puts Latinx individuals under the umbrella of “White,” but many reject this distinction. To complicate matters more, colorism, or shades of skin tones also effect how Latinx Americans choose to identify and/or are labeled by appearance. Other factors such as generation, cultural traits and traditions, and language complicate Latinx identity even more (Navarro, 2012).

In politics, Latinx Americans are continually confronted with issues immigration and reforms. DACA, the DREAM Act, and Latin American immigrants have sparked much controversy in recent years. Both pieces of legislation addressed the segment of Latinx Americans that were originally brought to the U.S. as children. These children lived the majority of their lives on American soil, educated in American schools, raised in American culture – making them American in all ways with the exception of a legal document. Some of these children grow up in mixed documented families. In the recent past, there have been numerous threats to deport “undocumented immigrants,” regardless of their participation within and contributions to American society. To deport any of these children, some now adults, would most likely result in separation of families and a displacement of individuals who argued that the U.S. was their rightful home, and they had no say in the original migration into the U.S.

The DREAM Act, Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act, allowed these children of immigrants to gain access to education, government funding for education, and conditional residency. DACA, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals Act, was passed under the Obama administration in 2012, and it allowed for minors to apply for deferment of deportation. In 2017, the Trump administration rescinded DACA in an attempt to end the program. However, since then, the act has undergone numerous legal battles that have resulted in the extension of the act. Currently, there are an approximate 700,000 DACA recipients in the U.S., and challenges to the program are still on going.

Xenophobia against Latinx communities have instigated much conflict and political debate. Latinx Americans continually strive to break long held stereotypes and maintain fair representation in popular culture and media. They do this while still retaining their cultural heritage and identity, in a complicated and deeply personal expression of individual identity.

BIOGRAPHICAL REFLECTION 6.1

A LITTLE GOES A LONG WAY

Before I began my career as a college professor, I was an elementary school teacher. Like most elementary school teachers, I have many stories to tell, and I will share one very important and special one.

Entering the teaching profession in central California in the 1990s, I found myself in a world where bilingual skills were in high demand, and bilingual classes were frequently taught and common to find. I was not bilingual, and I was assigned to a class where most students were native Spanish speakers. I even asked my principal to change my assignment to English-only. His response was that he would rather have a capable non-Spanish-speaking teacher teaching a bilingual class that a lesser teacher than did speak Spanish.

If you are thinking “Are you kidding me?” get in line. I thought my principal had lost it. But there I was, in a class where some of the students knew little English, and others were somewhat resentful that they had an African-American non-Spanish speaker for a teacher rather than a fluent Latino Spanish speaker. It was not an easy year, and I really didn’t know what I was doing half the time.

But one thing I did was refuse to do nothing. I enrolled in a beginning Spanish class at West Hills College Lemoore. I slowly but surely acquired linguistic skills in Spanish. I learned courtesies and “survival” language of course, but at least, I could give students permission to use the restroom and go to recess, using Spanish words. I took more Spanish, and even attended a summer Spanish language seminar. Within two years I was well—far from fluent, but much better off than before.

One day I was sitting in my classroom, and a monolingual Spanish-speaking parent came in my classroom. She said she needed help with understanding her son’s homework. For the next 15 minutes, I struggled with the Spanish I knew, but when she walked out, she said “Muchas gracias, Maestro.” I was practically faint from exhausting every Spanish word I knew, but that was my first successful conversation with a parent. What happened next nearly electrified me. Standing in front of my desk was a line of non-English speaking students with math books in hand, asking me for help, in Spanish. None of these students had said more than a few words to me the entire first four months of school!

When they saw that I could speak some Spanish, that was all they needed to know. The door of communication had been opened. A very happy conclusion to this awakening happened several years later. One of my former Spanish-speaking second graders was the valedictorian of her eighth-grade class. During her graduation speech, she thanked me as her favorite teacher, for of all things - being the only teacher who spoke Spanish to her. Now that is incredible, considering I was not fluent in Spanish.

To close, a little goes a long way. I am a strong advocate for learning a second language or at least part of a second language. It opened up doors of communication between my students and myself and gave me a respect and knowledge of a different culture that I never would have been privileged to know otherwise.

What motivated the writer to learn Spanish? What were some of the rewards for the time invested in learning it? What does this story tell you about the value of knowing a second language?

This story “A Little Goes a Long Way” by Daryl Johnson is licensed under CC BY NC ND 4.0

SUMMARY

Beginning in the early 16th century, Spanish speakers have inhabited North America; they created settlements and cultivated the land. Because of the complex history of colonization and intermarriage, Latinx Americans are difficult to define in racial and ethnic categories. After American efforts of westward expansion, many Latinx Americans found themselves citizens of the United States. Latinx communities continued to thrive in America throughout the 20th century, some settling permanently, others migrant workers. By the 1960s, many Latinx Americans joined civil rights movements, most of them concerned with labor reforms. Regardless of obstacles and discrimination, Latinx American communities continue to strive forward, determined to be recognized for their contributions to U.S. history. Like all other racial and ethnic minorities, their labor helped build this country and continues to demand progress and equity even today.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- What factors motivated Iberians to explore and colonize the Americas in the 16th century?

- How did westward expansion impact Spain and Mexico?

- Define U.S. foreign policies during the 19th century regarding Latin America. How did these policies impact Latin America?

- What issues drove the Latinx American civil rights movement of the 1960s?

TO MY FUTURE SELF

From the module, what information and new knowledge did I find interesting or useful? How do I plan to use this information and new knowledge in my personal and professional development and improvement?

REFERENCES

Foner, E. (2014). Voices of freedom: A documentary history: Volume 1. (4th ed.). W.W. Norton & Company.

Foner, E. (2014). Voices of freedom: A documentary history: Volume 2. (4th ed.). W.W. Norton & Company.

Locke, J. & Wright, B. (2019). The American yawp. Stanford University Press. http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html.

Ortiz, P. (2018). An African American and Latinx history of the United States. Beacon Press.

Rothenberg, P. S. (2016). Race, class, and gender in the United States: An integrated study. (10th ed). Macmillan.

Takaki, R. (1993). A different mirror: A history of multicultural America. Back Bay Books.