1.2: Theorizing Lived Experiences

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 150030

- Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, and Sonny Nordmarken

- University of Massachusetts Amherst via UMass Amherst Libraries

- Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, and Sonny Nordmarken

- University of Massachusett Amherst

You may have heard the phrase “the personal is political” at some point in your life. This phrase, popularized by feminists in the 1960s, highlights the ways in which our personal experiences are shaped by political, economic, and cultural forces within the context of history, institutions, and culture. Socially-lived theorizing means creating feminist theories and knowledge from the actual day-to-day experiences of groups of people who have traditionally been excluded from the production of academic knowledge. A key element to feminist analysis is a commitment to the creation of knowledge grounded in the experiences of people belonging to marginalized groups, including for example, women, people of color, people in the Global South, immigrants, indigenous people, gay, lesbian, queer, and trans people, poor and working-class people, and disabled people.

Feminist theorists and activists argue for theorizing beginning from the experiences of the marginalized because people with less power and resources often experience the effects of oppressive social systems in ways that members of dominant groups do not. From the “bottom” of a social system, participants have knowledge of the power holders of that system as well as their own experiences, while the reverse is rarely true. Therefore, their experiences allow for a more complete knowledge of the workings of systems of power. For example, a story of the development of industry in the 19th century told from the perspective of the owners of factories would emphasize capital accumulation and industrial progress. However, the development of industry in the 19th century for immigrant workers meant working sixteen-hour days to feed themselves and their families and fighting for employer recognition of trade unions so that they could secure decent wages and the eight-hour work day. Depending on which point-of-view you begin with, you will have very different theories of how industrial capitalism developed, and how it works today.

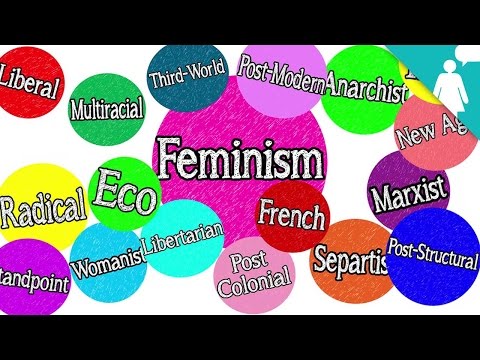

Feminism is not a single school of thought but encompasses diverse theories and analytical perspectives—such as socialist feminist theories, radical sex feminist theories, black feminist theories, queer feminist theories , transfeminist theories, feminist disability theories, and intersectional feminist theories.

In the video below, “Barbie explains feminist theories,” Cristen, of “Ask Cristen,” defines feminisms generally as a project that works for the “political, social, and economic equality of the sexes,” and suggests that different types of feminist propose different sources of gender inequality and solutions. Cristen (with Barbie’s help) identifies and defines 11 different types of feminism and the solutions they propose:

- Liberal feminism

- Marxist feminism

- Radical feminism

- Anti-porn feminism

- Sex positive feminism

- Separatist feminism

- Cultural feminism

- Womanism (intersectional feminism)

- Postcolonial feminism

- Ecofeminism

- Girlie feminism

What types of feminism do Cristen and Barbie leave out of this list? Do you agree with how they characterize these types of feminism? Which issues across these feminisms do you think are most important?

A YouTube element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: http://openbooks.library.umass.edu/introwgss/?p=24

Stuff Mom Never Told You – HowStuffWorks. (2016, March 3). Barbie Explains Feminist Theories | Radical, Liberal, Black, etc. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V3D_C-Nes60.

The common thread in all these feminist theories is the belief that knowledge is shaped by the political and social context in which it is made (Scott 1991). Acknowledging that all knowledge is constructed by individuals inhabiting particular social locations, feminist theorists argue that reflexivity—understanding how one’s social position influences the ways that they understand the world—is of utmost necessity when creating theory and knowledge. As people occupy particular social locations in terms of race, class, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, age, and ability, these multiple identities in combination all at the same time shape their social experiences. At certain times, specific dimensions of their identities may be more salient than at others, but at no time is anyone without multiple identities. Thus, categories of identity are intersectional, influencing the experiences that individuals have and the ways they see and understand the world around them.

In the United States, we often are taught to think that people are self-activating, self-actualizing individuals. We repeatedly hear that everyone is unique and that everyone has an equal chance to make something of themselves. While feminists also believe that people have agency—or the ability to influence the direction of their lives—they also argue that an individual’s agency is limited or enhanced by their social position. A powerful way to understand oneself and one’s multiple identities is to situate one’s experiences within multiple levels of analysis—micro – (individual), meso- (group), macro- (structural), and global. These levels of analysis offer different analytical approaches to understanding a social phenomenon. Connecting personal experiences to larger, structural forces of race, gender, ethnicity, class, sexuality, and ability allows for a more powerful understanding of how our own lives are shaped by forces greater than ourselves, and how we might work to change these larger forces of inequality. Like a microscope that is initially set on a view of the most minute parts of a cell, moving back to see the whole of the cell, and then pulling one’s eye away from the microscope to see the whole of the organism, these levels of analysis allow us to situate day-to-day experiences and phenomena within broader, structural processes that shape whole populations. The micro level is that which we, as individuals, live everyday—interacting with other people on the street, in the classroom, or while we are at a party or a social gathering. Therefore, the micro-level is the level of analysis focused on individuals’ experiences. The meso level of analysis moves the microscope back, seeing how groups, communities and organizations structure social life. A meso level-analysis might look at how churches shape gender expectations for women, how schools teach students to become girls and boys, or how workplace policies make gender transition and recognition either easier or harder for trans and gender nonconforming workers. The macro level consists of government policies, programs, and institutions, as well as ideologies and categories of identity. In this way, the macro level involves national power structures as well as cultural ideas about different groups of people according to race, class, gender, and sexuality spread through various national institutions, such as media, education and policy. Finally, the global level of analysis includes transnational production, trade, and migration, global capitalism, and transnational trade and law bodies (such as the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations, the World Trade Organization)—larger transnational forces that bear upon our personal lives but that we often ignore or fail to see.

How Macro Structures Impact People: Maquiladoras

Applying multiple levels of analysis, let’s look at the experiences of a Latina working in a maquiladora, a factory on the border of the US and Mexico. These factories were built to take advantage of the difference in the price of labor in these two countries. At the micro level, we can see the worker’s daily struggles to feed herself and her family. We can see how exhausted she is from working every day for more than eight hours and then coming home to care for herself and her family. Perhaps we could examine how she has developed a persistent cough or skin problems from working with the chemicals in the factory and using water contaminated with run-off from the factory she lives near. On the meso-level, we can see how the community that she lives within has been transformed by the maquiladora, and how other women in her community face similar financial, health, and environmental problems. We may also see how these women are organizing together to attempt to form a union that can press for higher wages and benefits. Moving to the macro and global levels, we can situate these experiences within the Mexican government’s participation within global and regional trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Act (NAFTA) and the Central American Free Trade Act (CAFTA) and their negative effects on environmental regulations and labor laws, as well as the effects of global capitalist restructuring that has shifted production from North America and Europe to Central and South America and Asia. For further discussion, see the textbook section on globalization.

Recognizing how forces greater than ourselves operate in shaping the successes and failures we typically attribute to individual decisions allows us see how inequalities are patterned by race, class, gender, and sexuality—not just by individual decisions. Approaching these issues through multiple levels of analysis—at the micro, meso, and macro/global levels—gives a more integrative and complete understanding of both personal experience and the ways in which macro structures affect the people who live within them. Through looking at labor in a maquiladora through multiple levels of analysis we are able to connect what are experienced at the micro level as personal problems to macro economic, cultural, and social problems. This not only gives us the ability to develop socially-lived theory, but also allows us to organize with other people who feel similar effects from the same economic, cultural, and social problems in order to challenge and change these problems.