3.1: Chapter 4- U.S. LGBTQ+ History

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 165127

- Clark A. Pomerleau

- SUNY Empire State College, Binghamton University, and SUNY Geneseo via Milne Publishing

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, students will be able to do the following:

- Explain the social construction of sex, gender, and sexuality.

- Summarize the history of nonnormative genders and sexualities, including homosexuality, bisexuality, and transgender identity, as well as queer identity and activism.

- Describe intersectionality from an LGBTQ+ perspective.

- Analyze how key social institutions shape, define, and enforce structures of inequality.

- Describe how people struggle for social justice within historical contexts of inequality.

- Describe several examples of LGBTQ+ activism, particularly in relation to other struggles for civil rights.

- Identify key approaches used in LGBTQ+ studies, including the study of LGBTQ+ history.

- Define key terms relevant to particular methods of interpreting LGBTQ+ people and issues, such as history and primary sources.

- Describe the relationship between LGBTQ+ history, political activism, and LGBTQ+ studies.

- Summarize the personal, theoretical, and political differences of the homophile, gay liberation, radical feminism, LGBTQ+ rights, and queer movements.

Introduction

Political organizing by oppressed Americans in the 1970s helped create lesbian, gay, bisexual or pansexual, trans, and queer history as a field of study. Why would people’s struggles for rights and freedom include wanting to be represented in historical accounts? Inclusive histories reflect the diversity of people in the United States, expose institutional discrimination against minorities, and outline their contributions toward the American democratic experiment. Like women’s history, LGBTQ+ history has developed through four stages that Gerda Lerner first identified: compensation, contributions, revision, and social construction.[1] LGBTQ+ historians first compensated for heterosexism and cissexism by finding LGBTQ+ people to reinsert into historical narratives, then determined how LGBTQ+ people contributed to history. As they analyzed primary sources, they slowly revised historical narratives through testing generalizations and periodization against evidence found by and about LGBTQ+ people. Finally, the field understood that sexual orientation and gender themselves are social constructions.

By the mid-1970s Joan Nestle and Deborah Edel had founded the Lesbian Herstory Archive (figure 4.1), collecting evidence of lesbian existence for the public, and Jonathan Ned Katz published a thick book of primary sources, Gay American History.[2] Stages one and two included uncovering the gender identity or sexual orientation of known figures like civil rights leaders Pauli Murray and Bayard Rustin. For stages two and three, scholars have debated how best to tell LGBTQ+ history—what counts as a first, who and what historians should emphasize, what places to highlight. Stage-four scholars stopped declaring that anyone who wrote intimately about someone of the same gender was “gay” or “lesbian” (why not bisexual?) and instead questioned how time-bound those terms are and debated how to identify people from time periods before society widely considered sexual orientation an identity.

This chapter takes the approach that LGBTQ+ history hinges on how concepts of sexuality and gender have changed to produce today’s identities, how queer Americans have formed community, and how these minority groups have forged movements using different tactics to gain rights and freedoms amid resistance and backlash. The chapter synthesizes formative, respected scholarship and includes some primary sources and recent research. It discusses the social construction of sex, gender, and sexuality; how LGBTQ+ intersects with other structures of inequality that social institutions have enforced; and how LGBTQ+ people have struggled for social justice despite resistance and setbacks.

Ideas about sexuality and gender have changed historically. This basic premise is one of the ways that we know that sex, gender, and sexuality are social constructs—that is, they are ideas that emerge from society and are changed through social action. Queer Americans have formed different types of communities in different historical eras, and LGBTQ+ people have struggled for social justice. The political struggles of LGBTQ+ people intersect with and have been influenced by other struggles for social justice, like civil rights and women’s rights.

Norms in Colonial America through the Late 1800s

White Settler Colonial Norms

Colonial Europeans established norms of marital reproduction and a sexual double standard within gender roles, which rendered what fell outside these two ideals unacceptable.[3] The Europeans’ encounters with nearly six hundred indigenous nations and all the ways these societies constructed gender and allowed varied sexual practices challenged European essentialist beliefs. Europeans tended to believe their Christian God created two fixed genders through sex assignment, set gender-divided duties, and made reproduction the purpose of sex. Thus, sex acts for purposes other than reproduction were signs of sin rather than any fixed identity. Yet European and, later, North American records give evidence that over 130 tribes recognized some individuals as women whom Europeans considered male or acknowledged some persons as men whom Europeans sexed female.[4]

The Spaniard Pedro Fages, for example, reported from his 1770 California expedition, “I have submitted substantial evidence that those Indian men who, both here and farther inland, are observed in the dress, clothing and character of women—there being two or three such in each village—pass as sodomites by profession. . . . They are called joyas, and are held in great esteem.”[5] Colonizers’ descriptions forced what later became known as two-spirit people into inadequate Western models, such as calling the joyas men and sodomites.[6] White settlers gradually amassed power through irregular warfare to impose their norms by murdering and dispossessing civilians. An indirect effect was queering indigenous genders by labeling variation sinful, criminal, and subject to punishment.[7]

The intersections of race and sexuality are foundational to colonial history. Consolidation of English power included writing white supremacy into Virginia law. By the 1690s colonialists divided people into categories of white, Negro, mulatto, and Indian and decreed enslaved status heritable through the mother. Many colonies enacted laws against interracial sexual relationships, but judicial systems prosecuted enslaved Black, free Black, and sometimes poor white people and not the plantation owners, ensuring that slaveholders’ power included the ability to rape without legal consequences.[8] Meanwhile, church and colonial laws drew on the dominant universalizing view of sexuality as simply behavior and not a basis for majority and minority social identities. Legal statutes deemed sodomy(oral or anal sex) unnatural, a sin and a crime.[9]

An English servant’s case illustrates how class also intersected with gender and sexuality in colonial America. Thomasine Hall lived as a girl, woman, and man before migrating to Virginia in 1627 as a male indentured servant, Thomas. There Hall’s sewing skills and sporadic dress in women’s clothes led neighbor women to question Hall’s gender. A group of women physically examined Hall three times. Amid rumors that Hall fornicated with a serving woman, the General Court assessed Hall’s gender. Examiners declared Hall had male genitalia. Hall’s response according to the court records was “hee had not the use of the mans parte” and “I have a peece of an hole [vulva].”[10] After townswomen refused the official ruling that Hall was female, the court decreed Hall must wear a combination of men’s and women’s clothing. We will never know whether Hall was intersex or what to call Hall’s sexual desire. Evidence suggests that, like other colonists, Hall enjoyed sex for pleasure outside of marriage. Anglo society was more bothered by fluidity than hybridity in wanting to fix Hall in place as both woman and man.[11]

Gender, racial, and class hierarchies established by the eighteenth century all helped shape twentieth-century LGBTQ+ organizing, but first people had to start forming communities based on their same-sex relationships.

Passionless Women, Romantic Friendships, and Vanguard Communities

From the American Revolution through the Civil War, defining sex as acts rather than as the basis for social identity continued. New gender norms, however, affected attitudes toward same-gender attraction. Americans in the early republic rejected previous colonial-era views of women as sexual beings. Instead, in the late 1700s, society considered Protestant, middle-class women less lustful and more spiritually moral than men. Idealizing women as passionless and sexually self-controlled compared with men’s “natural” sex drive constrained women’s public (though not private) behavior. Women reformers, whose organizing started in churches, asserted that society needed women’s input because of their Christian virtues.[12] The perception that women’s and men’s temperaments and desires were distinctly different facilitated wide acceptance of emotionally intense same-gender relationships alongside traditional marriage.[13] Occasionally, women who could support themselves lived together in so-called Boston marriages. Contemporaries were more likely to attribute a sexual component to romantic friendships between men, like the poet Walt Whitman’s with Peter Doyle, than to women’s relationships because of society’s continued belief that a penis was necessary for sex.[14]

Industrialization through the 1800s also played a role in forming communities based on sexual orientation. As industries spread, more people migrated to larger urban centers for factory and related jobs and into places for raw production that had extreme gender imbalances. Despite the prevalent view that same-sex affection was behavior anyone might show, rather than an identity, communities based on same-sex attraction formed. By the late 1800s, New York City had developed a subculture with identity terms like fairy for effeminate working-class men and queer for gender normative men who loved men.[15] New Orleans was another hub. An array of woman-woman relationships also existed, usually divided by class and race. Lesbians sometimes patronized bars, dance halls, and other public spaces where queer men congregated in the early 1900s.[16] Police from Los Angeles to New York might arrest women wearing pants and sporting short hair on charges of masquerading as men.[17] Same-sex relationships also occurred among men doing the physical labor that produced resources for industrial production—mining in California, Pacific Northwest logging, Seattle dock work, and railroad labor transporting goods—despite anti-sodomy laws that penalized these behaviors.[18]

How Sexology Pathologized Identity and Led to Solidifying the Straight State

Near the same time that communities developed self-definitions, European sexology repackaged marital reproduction and widespread views on sin and crime in the language of medical science. These sexologists articulated the concepts of “heterosexuality” and “homosexuality”.[19] The earliest sexologists campaigned against sodomy laws by asserting that same-sex attraction constituted a form of benign variation among humans—that is, harmless identities differing from those focused on reproducing. Most sexologists, though, argued same-sex attraction correlated with gender transgression as a pathological identity.[20] Newspapers had recurring exposés on working-class women passing as men for work and freedom. By 1892 the pathology model played a role in a Memphis insanity inquisition. This case exposed the plans of two women, whom relatives had thought to be romantic friends, to marry each other by having one assume a male identity. But when family members broke up this middle-class relationship, the distraught “masculine” half of the couple murdered her lover, and the defense lawyer her father hired used sexology to argue insanity.[21]

With the emergence of sexology, gender nonnormativity and same-sex attraction were now mental illness, in addition to being violations of religious ideas about sin and criminal laws. Although queer communities continued to spread, society’s validation of romantic friendships declined, and antivice campaigns arose by the 1920s and punished queer public expression. After Prohibition ended, federal and state officials enacted laws to control alcoholic beverages, to police respectability in bars. State agents held authority to revoke alcohol licenses if bar owners allowed the presence of undesirables like prostitutes, gamblers, gays, or lesbians (terms in the popular culture by the 1920s), who according to these laws, made establishments disorderly.[22] From the 1930s through the 1960s police freely busted bar patrons on suspicion of homosexuality.[23]

During World War II the military spread the normalization of heterosexuality and negative perceptions of “the homosexual.” Psychologists convinced military officials that homosexuality was a mental disorder that threatened morale and discipline. As eighteen million men moved through draft boards and induction stations, staffers asked questions designed to exclude gay men from service. Such questions heightened recognition that homosexuality existed even while pathologizing it. Officials feared that straight men would claim to be gay to avoid the draft; to deter this, they labeled anyone rejected for homosexuality as a “sexual psychopath” and gave employers the right to review draft records. Women’s auxiliary units started in World War II, but because criminal law usually ignored lesbian sex acts, the military did not similarly screen women recruits. Gay service members caught having sex or suspected of it faced humiliating expulsion after systematic inquisitions, which left several thousand men and dozens of women with undesirable discharges on their records.[24]

Gay and lesbian communities proliferated during and after the war, especially in cities with a military presence.[25] During the Cold War, federal, state, and local authorities redoubled efforts to achieve a straight state, including congressional laws and a presidential executive order against employing homosexuals in federal jobs.[26] Recent scholars have argued that the 1950s McCarthy Red Scare most victimized gay men and lesbians.[27] George Harris was among thousands fired. When the Central Intelligence Agency did a background check, they asked people from his Mississippi hometown about his sexual orientation. Suddenly jobless and homeless, Harris got a ride to Texas. He met Jack Evans soon afterward at a Dallas gay bar. As they dated, fell in love, and then lived together, they steered clear of bars to avoid arrest, and—fifty-nine years later—they became the first gay couple to marry legally in Dallas County.[28]

Watch

George Harris and Jack Evans are married in Dallas June 26, 2015, in this video. They were both in their eighties, having lived together for fifty-five years. A full video transcription can be found in the appendix.

- Describe what you witness in the video. What do you think is the relationship between the videographer and the couple? What terms, items, or actions featured in the video are you unfamiliar with?

- Given the history you learned in this chapter, why was this occasion so publicized and celebrated?

- Conduct a bit more research on George and Jack; how did their lives together reflect larger historical events from the 1960s to 2015?

From Homophile Movement to Gay Liberation

In the face of Cold War hostility and McCarthyism, gay and lesbian communities further institutionalized and began organizing a homophile movement for civil rights. Los Angeles gay men formed the Mattachine Society in 1951. Its founders, Harry Hay, Bob Hull, and Chuck Rowland, had organizing experience as U.S. Communist Party members. They structured Mattachine into secret cells to survive government infiltration.[29] The founders blended Marxist theory—that injustice and oppression were deeply embedded in societal structures—with inspiring tactics from the African American civil rights movement. They argued that repressive norms based in heterosexuality left homosexuals “‘largely unaware’ that they in fact constituted ‘a social minority imprisoned within a dominant culture.’” The founders sought to mobilize a large gay constituency through meetings and by creating homophile journals to produce a “new pride—a pride in belonging, a pride in participating in the cultural growth and the social achievements of . . . the homosexual minority.”[30]

Soon Mattachine grew to include many politically mainstream members who were anticommunist. The founders stepped down in favor of leaders who argued that the mostly white, middle-class, gay members were the same as heterosexual citizens, aside from the private sphere of love. They focused on gaining allies among heterosexual psychologists, clergymen, and public officials. Meanwhile, in San Francisco, Del Martin, Phillis Lyons, and their group, Daughters of Bilitis, also “were fighting the church, the couch, and the courts” for equality. Like the more male-run Mattachine Review and One magazine, Daughters of Bilitis’s journal, The Ladder(figure 4.2), consistently assured lesbians of their worth as respectable middle-class people deserving treatment equal to heterosexuals.[31] Chapters of both organizations spread to the East Coast and Midwest, forming a web of advocates for homosexual civil rights by the mid-1960s who published, lobbied, and picketed the White House and city governments for equality.

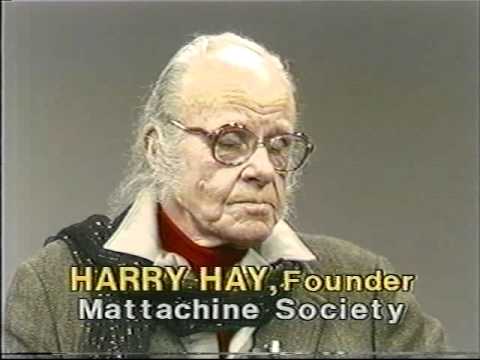

Watch

This 1983 interview by Vito Russo features Mattachine Society founder Harry Hay and Barbara Gittings, a founder of the Daughters of Bilitis and editor of The Ladder (https://youtu.be/RSO5Y8fGac4 and https://youtu.be/6nRJhce0xe0).

A YouTube element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://pb.libretexts.org/lgbtq/?p=81

A YouTube element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://pb.libretexts.org/lgbtq/?p=81

- What are some similarities and differences between Hay’s and Gittings’s experiences with political activism?

- What does Barbara Gittings mean when she states that “the very first gay pickets had maybe ten, fifteen, at the most twenty people who could afford to get out in public and do this”?

- What does Harry Hay mean when he argues it was important to “quit imitating the heterosexuals as much as we do”?

By the 1960s, various social movements were developing tactics to fight discrimination and inequality. Black civil rights legal work and direct action produced court-ordered desegregation, antidiscrimination law, and voting rights, although centuries of housing segregation, education, and job discrimination continued to racialize poverty. Frustrations rose in poor communities of color over police brutality and the dearth of economic opportunities. In 1965, gay and lesbian street youth organized in San Francisco. They and trans women often gathered at Compton’s Cafeteria, one of few places where they could meet. When Compton’s management called the police to deter drag queens’ and trans women’s patronage, a riot erupted. The next night, trans hustlers and street people picketed Compton’s and protested police brutality. Although the protest did not end abuse, a new collective militant queer resistance pushed the city to address queer and trans people’s rights as citizens.[32]

Three years later the Stonewall rebellion broke out after a New York City police raid. Stonewall Inn was a Mafia-run dive that blackmailed gay Wall Street patrons and used those funds to pay off police. In return, police gave the Stonewall advance warning of raids. Raids targeted those in full drag and trans sex workers like Sylvia Rivera. But raids could also ruin the lives of white, Black, and Latinx gay and lesbian customers; newspaper exposure often led to their being fired from jobs or evicted from housing. On June 28, 1969, there was no tip-off for the police raid. Trans and lesbian patrons resisted—refusing to produce identification or to follow a female officer to the bathroom to verify their sex for arrest. They also objected to officers groping them.[33] A growing crowd outside spontaneously responded to police violence by hurling coins and cans at officers, who retreated into the bar. Rioting resumed a second and third night. The gay poet Allen Ginsberg heard slogans being chanted and crowed, “Gay power! Isn’t that great! We’re one of the largest minorities in the country—10 percent, you know. It’s about time we did something to assert ourselves.”[34]

The Stonewall rebellion also did not stop police raids, but mainstream and gay coverage and leafleting spurred the creation of gay organizing that was more militant than previous homophile groups. The Gay Liberation Front sought to combine freedom from homophobia with a broader political platform that denounced racism and opposed capitalism. From the Gay Liberation Front arose the Gay Activists Alliance and its “zaps,” or surprise public confrontations with politicians to force them to acknowledge gay and lesbian rights.[35] Gay liberationists like Carl Wittman drew on past New Left antiwar student activism and the women’s liberation movement. Wittman’s “Refugees from Amerika: A Gay Manifesto” (1970) rails against homophobia, imploring gays to free themselves by coming out while also acknowledging it will be too dangerous for some. Wittman was attuned to the rise of lesbian feminism, which linked sexism and homophobia. Lesbian feminists emphasized women’s autonomy and well-being rather than identification as mothers, wives, and daughters who indirectly gained from what benefited men. Wittman deemed male chauvinism antigay and urged gay men to stop being sexist. Rather than mimic straight society, gay liberation should reject gender roles and marriage and should embrace queens as having gutsily stood out.[36]

Gay liberationists continued the fight to overturn homophobia in religion, psychology, and law. Gay Catholics formed Dignity in 1969.[37] The Unitarian Universalist Association urged an end to legal and social expressions of antigay discrimination in 1970, and the United Church of Christ ordained the first openly gay person in 1972. Episcopalians started Integrity in 1974. Mainstream Protestant denominations like the Presbyterian Church (USA), United Methodist Church, and Lutheran Church in America endorsed decriminalization but still disapproved of homosexuality. Fundamentalist evangelicals became increasingly vocal among denominations opposed to same-sex relationships and gender nonconformity. They began conservative religious organizing in response to progressive changes, propelling to celebrity status some ministers on the right such as Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, and Jim and Tammy Bakker. Some LGBTQ+ Christians flocked to the Pentecostal minister Rev. Troy Perry. He founded the Metropolitan Community Church denomination from a house-based service in 1968. Meanwhile, gay Jews in Los Angeles created the first gay synagogue in 1972.[38] Gay-friendly or gay-run houses of worship proliferated over the decade, but the majority of LGBTQ+ Americans faced discrimination in unwelcoming religious congregations.

In addition to trying to integrate religious spaces, gay liberationists demonstrated for the removal of homosexuality from the American Psychiatric Association list of mental disorders. Activists and gay counselors knew people were not sick for being queer. They used the research findings of their ally, the psychologist Evelyn Hooker; she had demonstrated, on the basis of personality tests she had conducted since 1957, that gay men were equally stable as heterosexual men and sometimes showed more resilience.[39] In 1973 the association voted unanimously to define homosexuality in its diagnostic manual as “one form of sexual behavior, like other forms of sexual behavior which are not by themselves psychiatric disorders.”[40] This was a major win on the long road to discrediting claims that homosexuality was a mental illness and the conversion therapies designed to “cure” homosexuals. However, in 1980 the American Psychiatric Association’s third manual introduced “gender identity disorder of childhood” and “transsexualism” as disorders, indicating it preserved a concern about variety in gendered behavior, which sustained forced conversion programs for children and adolescents without increasing access to medical services that some trans adults wanted.[41]

Politically, in the 1970s efforts to gain equal rights ordinances and to elect lesbian and gay politicians became fruitful. Elaine Noble joined the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1974, and Harvey Milk won a seat in the San Francisco Board of Supervisors election in 1977.[42] The conservative campaign of Anita Bryant that overturned Florida’s Miami-Dade County gay rights ordinance in 1977 galvanized conservatives on the Christian right and gay activists nationwide against or for, respectively, extending equal rights regardless of sexual orientation. The next year activists managed to prevent California from passing an initiative that would have barred gay teachers from working in public schools. But cities with antigay campaigns experienced increased violence against gay and lesbian people and their businesses, centers, and churches, culminating in the murder of Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone by a former board of supervisors member and ex-policeman, Dan White, in 1978. White was convicted of manslaughter and served five years.[43]

Amid the volatile cultural battles of the 1970s, there were some victories. By the end of the decade, activists had decriminalized themselves in just under half the nation by overturning twenty-two state sodomy statutes, had countered antigay city initiatives, and had convinced the Democratic Party to include a plank against sexual orientation–based discrimination in its 1980 platform.[44] They would have to wait until 2003 for the Supreme Court decision on Lawrence v. Texas to strike down sodomy laws nationwide.[45]

The 1970s also saw a cultural renaissance of LGBTQ+ institution building and cultural productions through publishing and music. More Americans came out despite the real hazards of family rejection, violence, and legal discrimination. Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson survived such dangers to start Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) in 1970. STAR, the first organization led by trans women of color, created the first homeless queer youth and sex worker shelter in North America. By recognizing links among homophobia, transphobia, racism, and classism, STAR filled needs other early gay liberation groups were not considering. More often gays and lesbians organized safe spaces through bars, gay baths, bookstores, discos, sports leagues, and musical ensembles.[46] As the 1970s continued, feminist lesbians of color took the lead in advocating for “the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking.”[47] This important way of analyzing the world would become known as intersectionality.

Watch

Billy Porter provides a brief history of queer political actions that predate the Stonewall rebellion (https://youtu.be/XoXH-Yqwyb0).

A YouTube element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://pb.libretexts.org/lgbtq/?p=81

- What surprised you about this video? What did not surprise you? What LGBTQ+ organization or historical event described in this video was new to you? Conduct some more research to better understand that organization’s or event’s goals and accomplishments.

- What LGBTQ+ organizations or movements are active now, and how are they similar to or different from the movements discussed earlier?

Responding to AIDS

In the 1980s, the emergence of a deadly epidemic marked a crossroads for LGBTQ+ activism and institution building. A 1981 newsletter from the Centers for Disease Control reported five Los Angeles gay men had contracted an unusual pneumonia typically found in immune-compromised people. Then the New York Times stated that a rare, aggressive skin cancer had struck forty-one recently healthy homosexuals.[48] By late 1982, related immunosuppression cases existed among infants, women, heterosexual men, intravenous drug users, and hemophiliacs. The mortality rate of the original patients was 100 percent. Panic spread as media, many government officials, and the gay community asked what linked the affected gay men. Connecting a deadly disease, ultimately called acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) to gay male sexuality provided a new rationale for discriminatory laws and harassment as the political power of the Christian Right continued to ascend.[49]

In response to AIDS, LGBTQ+ Americans organized new institutions and created new methods to get needed resources, which furthered lively debates over political tactics. Because the health care system failed to address the epidemic’s causes and consequences, New York City gay men founded Gay Men’s Health Crisis in 1982. It became a model for AIDS service organizations that offered information and support to prevent or treat the disease.[50] Lesbians contributed experience from the women’s health movement, where they had countered male-dominated medicine with their own research and support networks. Black Panther–sponsored free breakfasts and community health clinics became a model for AIDS service organizations.[51] By 1983 the group People With AIDS had mobilized nationally to demand control over decisions about their care and to draw attention to scapegoating that resulted in job loss and refusal of hospital treatment. They released “The Denver Principles,” which asserted their responsibility to use “low-risk sexual behaviors” without denying their right to “satisfying sexual and emotional lives.”[52] The gay community split on whether to blame casual sex with multiple partners for the crisis and how to contain the spread of the disease. As city public health officials sought to shut down bathhouses and bars that had spaces for sex, some gay activists agreed with the precaution, but others saw the campaign as more antigay harassment. Those opposed to closures argued that instead of driving gay sex further underground, public sites like bathhouses should become education centers for safer sex practices. Meeting spaces were places where the community organized efficiently to respond to AIDS.[53]

A major contributor to the AIDS epidemic was willful neglect by the federal government. For the first five years of the epidemic, President Ronald Reagan remained silent about it. In 1986 he and governors from both parties proposed cutting government spending on AIDS. That year the Supreme Court ruled in Bowers v. Hardwick that gay adults did not have constitutional privacy rights that would protect them from prosecution for private, consensual sex.[54] The Justice Department announced that federal law allowed employment discrimination based on HIV/AIDS status. When Reagan spoke briefly at the Third International Conference on AIDS in 1987 in favor of testing, over twenty thousand of the thirty-six thousand Americans diagnosed with AIDS had died. Congress prohibited using federal funds for AIDS education that condoned same-sex behavior but mandated testing of federal prisoners and immigrants to bar entry to those with HIV.[55]

This spurred high-impact radical organizing. Larry Kramer and cofounders formed the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) in 1987. It further publicized the New York City slogan “Silence = Death” in demonstrations. ACT UP dramatically disrupted Wall Street, the Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control, and Saint Patrick’s Cathedral to protest the high cost of AZT (the first drug treatment) and the appointment of a loudly homophobic Catholic cardinal to the Presidential HIV Commission. ACT UP chapters spread to other cities; the groups became known for their insistence on action and their reclaiming of the term queer.[56] Keith Haring’s graffiti art spread the message. Cleve Jones created a memorial for people lost to AIDS, inviting loved ones to create three-by-six-foot panels for the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt (figure 4.4). During the second March on Washington in October 1987, volunteers laid out 1,920 panels on the National Mall.[57]

In tandem with responses to AIDS, often-overlooked portions of LGBTQ+ Americans organized. Trans people were disproportionately poor owing to job discrimination and devastating budget cuts to AIDS programs, welfare, and health programs. For-profit centers sold medical procedures for gender transition at high costs. Bisexuals started forming social and then political rights groups, including the National Bisexual Liberation Group in 1972 based in New York City, San Francisco’s Bisexual Center in 1976, and the national BiPOL in San Francisco in 1983. When the 1987 March on Washington organizers would not include “bi” or “trans” in the march’s title or list of demands, both constituencies argued that the category “gay and lesbian” was not inclusive.[58] New trans groups arose with transnational scope, including FTM International (advocating for the female-to-male trans community) and International Foundation for Gender Education, along with periodicals like Metamorphosis and Tapestry.[59]

With the development of intersectional theories and activism, gay, lesbian, and bi Americans who also held other minority statuses founded organizations in the 1970s and throughout the 1980s. Gay American Indians was founded in San Francisco in 1975, and in 1987 the group joined American Indian Gays and Lesbians. Conferences of the American Indian Gays and Lesbians produced the consensus that two spirit was the preferred term for gender-expansive Natives.[60] The National Rainbow Society of the Deaf (1977) grew from its Florida origins to hold annual conventions around the country as Rainbow Alliance of the Deaf (1982) and to become a force for advocacy. The national Asian Pacific Lesbian Network was founded when organizing for the 1987 march. African American gays and lesbians created religious community with Unity Fellowship Church (1985) and secular groups. When gay men formed the National Association of Black and White Men Together (1981), with local affiliates across the country, they ushered in a new form of interracial organizing. Some queer people of color joined with white gays and lesbians for antidiscrimination and AIDS work and criticized white-dominated queer communities for their racism. Queer people of color worked with other people of color for civil rights, poverty issues, and anti-imperialism while objecting to those communities’ homophobia, sexism, and transphobia. Queer people of color needed their own queer groups by race as respites from coalition work.[61]

Listen

In a 1989 Making Gay History interview (https://go.geneseo.edu/larrykramer), ACT UP founder Larry Kramer describes being a student at Yale University in the 1950s, before the Stonewall rebellion, and then how he tried to organize gay men to fight the AIDS crisis in the 1980s.

- What were some of the challenges that Kramer had to overcome in his lifetime, whether at college or in the fight against AIDS?

- Queer theory emerged during a very turbulent period in U.S. history, with AIDS decimating gay male communities. The anger at the apathy of the U.S. government, in the face of tens of thousands of men dying, drove the radical activism of ACT UP. Describe some of the tactics they used. What do you think of them?

- In the interview, Kramer says there had been “a lot of change and no change” between when he was in college in the 1950s and the late 1980s. What do you think he meant by that? If he were interviewed today, do you think he’d say the same thing, and why?

Mainstream and Queer Goals

Beginning in the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s, new drug therapies prolonged the lives of people living with AIDS. Although radical, multicommunity AIDS activism continued, work for mainstream legal protections and rights dominated LGBTQ+ activism. LGBTQ+ Americans and supporters sought inclusion in the military, the passage of antidiscrimination laws, and marriage equality. After a campaign promise to end military exclusion, President Bill Clinton responded to pushback from military leaders with a compromise. He supported a congressional law that instructed LGBTQ+ service members to remain closeted and military officials not to pursue people for discharge (figure 4.5). Ironically, this “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy increased discharges of gay service members and continued violence against them until its repeal by President Barack Obama in 2010 ended discrimination based on sexual orientation (but not gender identity).[62] President Clinton was more effective with his executive order to end antigay discrimination in federal government in 1998 than with his military policy.[63]

Violence against LGBTQ+ Americans continued, including the rural murders of Brandon Teena and then Matthew Shepard. Both murders gained so much media coverage that they eventually became movies. Outrage against antigay violence and prejudice led New York ACT UP members to form Queer Nation in 1990 and inspired groups like the Pink Panthers (1990) and Lesbian Avengers (1992). Their direct actions to liberate sexuality and gender from heteronormativity were defiantly queer. A particularly controversial tactic was exposing the closeted homosexuality of antigay politicians and pundits. New federal hate-crime tracking confirmed the scope of anti-LGBTQ+ violence, indicating that over 10 percent of violent crimes motivated by bias against the victim’s identity were based on sexual orientation, putting that category behind only race and religion. Congressional passage of the Hate Crimes Sentencing Enhancement Act (1994) included gay bashing as a federal crime to ensure fairer trials.[64]

Read

Read Dignity & Respect: A Training Guide on Homosexual Conduct Policy, a pamphlet published by the U.S. Army in 2001 that explains to soldiers the new homosexual conduct policy that would become known as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (https://archive.org/details/DignityRespectADepartmentOfDefenseTrainingGuideOnHomosexualConductPolicy).

- Does this pamphlet help you better understand the army’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy? Why or why not?

- According to the pamphlet, the army’s goal was to fairly enforce this new policy, to promote unit cohesiveness and readiness. Do you think this pamphlet would have helped achieve that goal?

- What is or isn’t in the policy that might explain why harassment and violence against gay service members continued while it was in effect?

State legislatures and popular ballots featured both antidiscrimination and antigay measures, creating grassroots organizing for and against protecting LGBTQ+ Americans from being fired or excluded from jobs, housing, and public accommodations. Cultural conservatives lamented the gradually increasing acceptance of LGBTQ+ people as celebrity musicians and television and film stars slowly started to come out and weathered backlash to continue their careers. Meanwhile, the Hawaii state supreme court win Baehr v. Miike temporarily legalized same-sex marriage there in 1996.[65] National LGBTQ+ organizations pushed to extend marriage equality nationwide. Over the next decade states split on whether to ban or legalize marriage equality. Popular support steadily grew in the first years of the 2000s, reaching 60 percent in 2015 when the Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges that the Fourteenth Amendment guarantees same-sex couples the right to marry (figure 4.6).[66]

Groups that centered young, trans, poor, and minority people warned in the early 2000s that hate-crime legislation and nondiscrimination laws connected to it would further hurt the most marginalized Americans. Dean Spade cautioned that sentences mandatorily extended for hate crimes strengthened “the criminal punishment system” that targets poor (and trans) people of color.[67] Likewise, some feminist and queer activists opposed the costly push for marriage equality because it supported only heteronormative relationships.[68] Paula Ettelbrick, among the first, argued in 1989 against endorsing one family form instead of destigmatizing unconventional relationships and sexual expression. Lisa Duggan has argued for broad coalitions to gain universal benefits instead of tying needs like health coverage to employment and marriage.[69]

Conclusion

LGBTQ+ history in the United States has witnessed profound transformations in meanings, the social construction of identities, and how LGBTQ+ people have used collective action to fight for rights and equality. For centuries laws touted marriage as the place for reproductive sex but allowed some men sex for pleasure across race and class. When sex was considered simply a form of behavior and society believed women and men were fundamentally different, same-gender intimacy that was not obviously sodomy was deemed unremarkable. But as sexologists categorized sexuality into normal or pathological identities, psychology and medical science joined the church and state as key social institutions that demonized LGBTQ+ people. Communities of gay and bisexual men, lesbian and bisexual women, and trans people multiplied in the 1950s despite heightened repression, and a portion of these minorities organized for equal rights. Even the HIV/AIDS epidemic, blamed on and falsely identified with gays, could not stop LGBTQ+ organizing. Activists further developed radical tactics from the 1970s to call for liberation from heteronormativity. Legal gains have been arduously won, but foundational power imbalances based on race, class, gender, ability, and citizenship persist. Nonetheless, both legal and cultural changes continue to transform society.

Profile: Institutionalizing Sexuality: Sexology, Psychoanalysis, and the Law

Jennifer Miller and Clark A. Pomerleau

Sexology, Civil Rights, and Criminalization

European scientists and social scientists developed the social science known as sexology to understand human sexuality. They used biology, medicine, psychology, and anthropology to support beliefs that privileged binary gender identities (man or woman) and reproductive sex while trying to account for gender and sexual diversity. What was at stake for the men who created sexology varied: some felt same-sex attraction, some were sympathetic to those who did, others opposed same-sex behaviors. Their findings became arguments for and against criminalizing same-sex behavior. This profile’s history of sexology prioritizes primary sources to consider how sexologists explained diversity in gender and sexuality and how the field’s spokespersons shifted from an initial focus on social justice to creating oppressive, pathologizing diagnoses. Knowing this history helps us understand sexology’s long-reaching implications as a method by which people worldwide have been taught about queer and trans people.

The earliest form of sexology combatted legal discrimination. The German lawyer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (figure 4.7) drew on Plato’s Symposium for his 1860s theory that male-male love was biologically inborn and therefore natural.[70] Ulrichs used the term urning for a man who desired men and believed the urning’s desire reflected an internal female psyche. After telling his family he was an urning, Ulrichs—freed from his secret—lobbied to repeal sodomy laws. He maintained that consenting adult men who were not being publicly indecent had a civil right to express their love without state persecution. Ulrichs hoped to influence national legal reform as German states unified, so he published “Araxes: Appeal for the Liberation of the Urning’s Nature from Penal Law. To the Imperial Assemblies of North Germany and Austria” in 1870.[71] The next year, Germany’s assembly refused change and retained a sodomy law in the new law code. Paragraph 175 of the German Imperial Penal Code stated, “Unnatural vice committed by two persons of the male sex or by people with animals is to be punished by imprisonment; the verdict may also include the loss of civil rights.”[72] Germany would not decriminalize homosexuality until 1969.

Although his argument was unsuccessful, Ulrich’s work influenced other sexologists and became part of a growing field. His contemporary, the Austro-Hungarian human rights journalist Karl-Maria Kertbeny, coined the words heterosexual and homosexual in 1868 as two forms of strong sex drive apart from those that pursued reproductive goals. Out of compassion for a friend who killed himself after being blackmailed for same-sex attraction, Kertbeny argued that sodomy laws violated human rights.[73] The German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing adopted Kertbeny’s terminology and Ulrichs’s view that men who loved men had womanly desire (figure 4.8). Krafft-Ebing, however, considered anything outside reproductive sex to be an inferior, immoral deviation, which he called degeneracy. His Psychopathia Sexualis, Contrary Sexual Instinct: A Medico-Legal Study (1894) provided an elaborate taxonomy of “pathological manifestations of the sexual life.” The taxonomy included sexualizing an object (fetishism), sexually enjoying pain (masochism, which Krafft-Ebing considered natural for women), and sexually enjoying inflicting pain (sadism, which Krafft-Ebing considered natural for men). Krafft-Ebing claimed same-sex attraction was usually innate but could sometimes be produced as a result of exposure to other forms of “sexual deviance” like masturbation.[74] Like Ulrichs and Kertbeny, Krafft-Ebing hoped to influence jurisprudence with psychological claims, but to him, “The laws of all civilized nations punish those who commit perverse sex acts. Inasmuch as the preservation of chastity and morals is one of the most important reasons for the existence of the commonwealth, the state cannot be too careful, as a protector of morality, in the struggle against sensuality.”[75] Sexology’s language has continued to aid the power to police sexuality legally and has contributed to critiques of that power.