2.3: The Scientific Method

- Page ID

- 167172

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

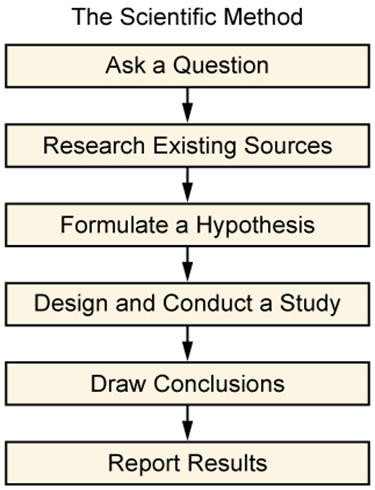

Humans and their social interactions are so diverse that these interactions can seem impossible to chart or explain. However, this is exactly why scientific models can work for studying human behavior. A scientific process of research establishes parameters that help make sure results are objective and accurate. Scientific methods provide limitations and boundaries that focus a study and organize its results. The scientific method involves developing and testing theories about the world based on empirical evidence. It is defined by its commitment to systematic observation of the empirical world and strives to be objective, critical, skeptical, and logical as best as possible. No human study can be completely value free, but the scientific method includes acknowledging researcher bias or perspective as part of the findings report. It most often involves a series of prescribed steps (see chart above) that have been established over centuries of scholarship.

Problems and Issues in Sex Research Sample Methods

Sexuality is often considered a taboo subject in modern Western society, therefore, the field is among the most difficult to obtain reliable data. However, with the use of the survey method, information is easily obtained from large groups. Because of this, there is the potential for both representativeness and the size of the samples to be more adequate for generalizations to larger groups of people (Griffitt & Hatfield,1985). Using a voluntary large group to identify the traits and habits of the population can be both much more reliable, and not completely accurate. Focusing on a small case study or a small group in an experiment to draw a conclusion about the general population can be misleading, because the individuals who choose to participate in an experiment about sexuality are already likely more open to discussing sex than the general population. One of the most comprehensive sexuality studies in the U.S known as The Janus Report was largely criticized for not actually having information from a random sampling. The Americans in the study were willing to talk about and engage in wider varieties of sexual behaviors.

Volunteer Bias

Volunteer bias can create major problems for any type of research. Some psychologists believe that people who volunteer for research have different characteristics from those who don’t volunteer. This is thought to be especially true in regards to sex research, with sex being a more taboo topic for some. The Volunteer Bias and Personality Traits in Sexual Standards research sought to see if there was stronger volunteer bias in sex surveys, versus a survey of a more general topic. The study surveyed 126 males and 128 females in an introductory Psychology course at a Midwestern Canadian university. The study began with the students completing the Personality Research Form developed in 1967 by Psychologist Douglas N. Jackson to assess the students' personalities. They were then assigned to be mailed either a sexual standard’s questionnaire (experimental group) or parent-child relations questionnaire (control group). Returning these questionnaires was not required for the course. It was hypothesized that the volunteers who returned the sexual standards survey would stand out as an atypical group. However, when relating back to the personality research forms, personalities were about the same as those who returned the parent-child relations questionnaire.

Researcher Bias

Through the interdisciplinary study of human sexuality and corresponding research, we are able to obtain more information about the sexual aspects of human beings. As human beings, researchers are conducting research about topics that relate directly to them. Often, researchers will have ideas, values, or opinions based on their cultural or social status that may skew some data. While this is certainly to be expected, it is easily assuaged by full transparency surrounding the research. A section in any research report can include the researcher’s hypothesis prior to undertaking the study, so that the reader can understand where the researcher is coming from. Clear description of methods and findings plus an analysis of the implications also helps validate research findings. While it is problematic if researchers do not recognize their own biases and include them in their findings, these simple steps can avoid this type of pitfall. Another type of bias can come from those who have a vested interest in keeping a certain narrative about whatever phenomena is a proposed topic of study. In some cases, intervention from lobbyists and conservative groups prevented major funding of certain research making discovery more difficult. Those special interest groups may argue that there is no value in the study and in fact would serve more harm than good. This is a slippery slope, and sometimes, the research that can be life saving ends up being the most controversial.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study was a clinical study conducted between 1932 and 1972. The study was intended to observe the natural history of untreated syphilis. As part of the study, researchers did not collect informed consent from participants and they did not offer treatment, even after it was widely available. The study ended in 1972 on the recommendation of an Ad Hoc Advisory Panel, convened by the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs, following publication of news articles about the study. In 1997, President Clinton issued a formal Presidential Apology, in which he announced an investment to establish what would become The National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care at Tuskegee University. Many records can be found in the National Archives. After the study, sweeping changes to standard research practices were made. Efforts to promote the highest ethical standards in research are ongoing today.

Content source: National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention