7.8: Identity Terms

- Page ID

- 167850

Bias and discrimination play out in varying ways. As we learned in Chapter 5, labels regarding how we want to be addressed can either constrain or free us. Choice of pronoun is now a more widely accepted practice in various social settings, which has allowed for individuals to create their identity in a way that feels authentic to who they are. Just like our pronouns, other aspects of our identity get named, and sometimes the naming is not done by the people who identify in a specific category, but instead by those in power. Language is political, hotly contested, always evolving, and deeply personal to each person who chooses the terms with which to identify themselves. To demonstrate respect and awareness of these complexities, it is important to be attentive to language, and to honor and use individuals’ self-referential terms (Farinas and Farinas 2015). Below are some common identity terms and their meanings. This discussion is not meant to be definitive or prescriptive, but rather, aims to highlight the stakes of language and the debates and context surrounding these terms, and to assist in understanding terms that frequently come up in classroom discussions. While there are no strict rules about “correct” or “incorrect” language, these terms reflect much more than personal preferences. They reflect individual and collective histories, ongoing scholarly debates, and current politics. Let’s look at two examples.

“Disabled people” vs. “People with disabilities”

Some people prefer person-first phrasing, while others prefer identity-first phrasing. People-first language linguistically puts the person before their impairment (physical, sensory or mental difference). Example: “a woman with a vision impairment.” This terminology encourages nondisabled people to think of those with disabilities as people (Logsdon 2016). The acronym PWD stands for “people with disabilities.” Although it aims to humanize, people-first language has been critiqued for aiming to create distance from the impairment, which can be understood as devaluing the impairment. Those who prefer identity-first language often emphasize embracing their impairment as an integral, important, valued aspect of themselves, which they do not want to distance themselves from. Example: “a disabled person.” Using this language points to how society disables individuals (Liebowitz 2015). Many terms in common use have ableist meanings, such as evaluative expressions like “lame,” “retarded,” “crippled,” and “crazy.” It is important to avoid using these terms. Although in the case of disability, both people-first and disability-first phrasing are currently in use, as mentioned above, this is not the case when it comes to race (Kang, et al., 2017).

Just as we now are choosing to include pronouns into introductory phases of interpersonal relations and group events or situations, other parts of identity can also be added if those invited in wish to disclose. As nothing is static in the culture, these practices may shift too, but for now, if you are wondering how to implement something like this in a group you are facilitating, it is best to self-disclose and make space for others to share how they’d like to be referenced. If they do not share a part of their identity you think is important, be able to let that go and allow them to be seen and named how they wish.

The effects of ableism are widespread, and profound and are often unacknowledged by the nondisabled public. Unlike other identities, anyone can become disabled at any time in their life, yet it is often the last one discussed by the general population, even though disabled people are the largest global minority group. Whether it’s due to society’s delayed collective awakening to ableism, it’s avoidant fears of becoming part of the largest minority, or it’s well practiced solution of sweeping it under the rug, the variations and degrees of disabilities and topics surrounding it require a more prompt attentiveness from us to begin unpacking and addressing it all.

There is not a monolithic disabled experience, there are countless spectrums, types, and ways that people experience disability, there are endless ways in how ableism shows up for each individual, sub-community, and intersection. The majority of accessibility advocacy work reflects the urgency of removing barriers in basic daily activities, meeting needs, and increasing visibility and overshadow the rest - often leaving sexuality and relationships as last or completely disregarded as topics under the umbrella of disability.

“Most everyone has felt those Unwelcome, crawling feelings - Unfavorable, Undesirable, Unwanted; the “doing them a favor” by preemptively rolling away on your cart of baggage. But being a human in a body that is neglected, mistreated, tokenized, infantilized (on top of it all) carries its own cruel irony.”

In my essays in Where Shame Dies, a collection of work on disability and sexuality, I address these topics from the lens of my own experiences and observations, primarily about the effects of having obviously visible physical differences. Visibly disabled people face automatic discrimination whether it be abuse, aggressive harassment, micro aggressions, or “friendly” avoidance alongside harmful assumptions, which all run rampant. Others immediately assess your worth, function, desirability, or humanness as a whole.

“I know it’s up to every individual to figure things out for themselves and how they relate to those around them - But how are we supposed to put ourselves in the conversation when we’re left in the other room? How do we get/feel invited to the circle when we seem covered in red flags? How can we rectify the twisted connotation that disabled means nonsexual when you perpetuate it? How can we process our layers of trauma when we’re too busy putting you at ease? How do we put ourselves out there when people with disabilities are 3x more likely to be sexually assaulted than literally anyone else? How can we expect healthy relationships when you’ll either love us or fuck us but rarely both?”

The more visibly different or disabled a person is, the more bias in romantic relationships will dominate interactions despite any relevance to potential further connection. Even for those who have done the work to address their own ableism, conscious efforts to move with more humanity cannot fully undo generations of programming in the subconscious. It shows up in loved ones behaving as if they cannot be honest with what they want or do not want from you, or romantic endeavors not being able to bring themselves to commit to exploring a committed relationship with you, or them unknowingly using you for more of their own ego-based benefit than a reciprocal connection.

“It’s being too much and not enough; the ever-looming fog of burden. It’s bubbles of grief that speak words of exhaustion of this corporal form. It’s the culmination of patterns and sickly reminders making it feel like my insides are going to crawl out my mouth. It’s the risks in being vulnerable, weighing like a punishment. It's being in a body with talents of opening others up just to further perfect the art of self-preservation. The dark magic of seeing and not being seen.”

Due to both societal and internal ableism, people often view disability as an individual issue to navigate or overcome, but especially in sexuality and romance, the biggest challenge is rooted in other’s perceptions and having to either educate others for them, or unlearn absorbed notions of shame and worth.

Assuming a disabled person is nonsexual or undesirable to any able-bodied or nondisabled person is suggesting that disabled people are automatically excluded from the full range of the human experience. It’s a common misconception full of privilege and ignorance that can cause harm and create more barriers to connection and pleasure for both disabled and nondisabled people at large.

"The George Floyd mural outside Cup Foods at Chicago Ave and E 38th St in Minneapolis, Minnesota" by Lorie Shaull is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

People of color vs. Colored people

People of color is a contemporary term used mainly in the United States to refer to all individuals who are non-white (Safire 1988). It is a political, coalitional term, as it encompasses common experiences of racism. People of color is abbreviated as POC. Black or African American are commonly the preferred terms for most individuals of African descent today. These are widely used terms, though sometimes they obscure the specificity of individuals’ histories. Other preferred terms are African diasporic or African descent, to refer, for example, to people who trace their lineage to Africa but migrated through Latin America and the Caribbean. Colored people is an antiquated term used before the civil rights movement in the United States and the United Kingdom to refer pejoratively to individuals of African descent. The term is now taken as a slur, as it represents a time when many forms of institutional racism during the Jim Crow era were legal.

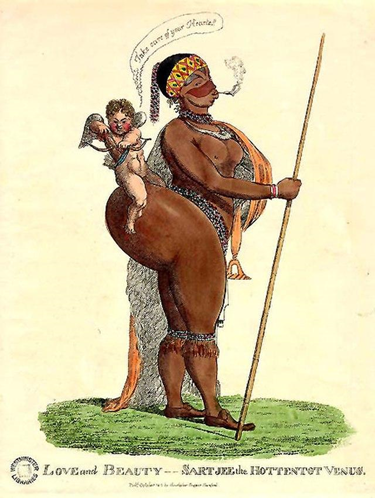

"Black women have always been these vixens, these animalistic erotic women. Why can't we just be the sexy American girl next door?" - Tyra Banks on being a sex symbol

Black women in the media are portrayed as sexual objects, and this is not an accident. Hollywood works hard at perpetuating dehumanizing stereotypes of people of color, and Black women are often subject to this. The media is a powerful outlet to the entire world, and has a significant impact on molding the general public to think a certain way. In the media, we see Black women portrayed as "sexually willing characters often inviting of sexual objectification. [These] transcend the confines of the media, and penetrate and manifest themselves in everyday society" (Ntinu 1).

Life and culture as we know it are greatly impacted by the media. So, when all we see is Black women playing that same old role of the hoochie mama, and we walk down the street and hear a man catcalling a Black woman with some sexualized slur, we know this to be learned behavior. We know that because of the media misrepresenting Black women in every way possible; there are people that are going to live their day to day lives believing everything they hear in the media. There are people that will see what's on television, whether that be their favorite show, movie, music video to their favorite song, and believe every last bit of it. Black women are constantly portrayed as sexual beings. Their bodies and their innocence have been stripped away from them since adolescence, and not much is being done to save them. I say all of this to say that representation matters. The intersections of race and gender are things that a Black woman cannot escape. Those two things follow her wherever she goes.

Excerpts adapted from: Matthews, Annalycia D., "Hyper-Sexualization of Black Women in the Media" (2018). Sociology Student Work Collection. 22. Full text available at: https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/gender_studies/22