4.1: Module 9 – Gender Through a Health Psychology Lens

- Page ID

- 150113

Module 9: Gender Through a Health Psychology Lens

Module Overview

Unequivocally, women are sicker than men. They report more pain, more mental health problems- including a higher diagnosis rate of most psychological disorders (See Module 10), and report more physical symptoms. Despite this increase in overall illness, women live longer than men! In fact, men are more likely than women to die in 9 or the 10 leading causes of death!

The purpose of this module is to explore the gender differences in mortality and morbidity rates, as well as general statistics regarding men and women’s health. We will also explore the differences between men and women’s health behaviors, including negative health behaviors that may impact their own mortality and morbidity. Finally, we will briefly discuss environmental factors that may impact an individual’s perceived and actual physical well-being.

Module Outline

- 9.1. Mortality

- 9.2. Morbidity

- 9.3. Health Behaviors

- 9.4. Environmental Factors and Physical Health

Module Learning Outcomes

- To understand the difference between mortality and morbidity with respect to gender

- To identify the leading causes of mortality in the United States

- To identify and explain the morbidity factors that contribute to mortality

- To identify the gender differences among these morbidity factors

- To identify the implications of positive and negative health behaviors on morbidity

- To identify the impact of environmental factors such as marriage, parenting, and bereavement on one’s overall well-being

9.1. Mortality

Section Learning Objectives

- To increase knowledge about factors that contribute to men and women’s life expectancy

- To identify leading causes of death in men and women

- To increase knowledge on crime statistics specific to men and women

9.1.1. Life Span/Expectancy

Men die younger than women across all ethnicities within the United States. Although boys are born at a slightly higher rate than girls, more boys die than girls at every age group. After birth, males have higher death rates than females. In fact, infant girls in the NICU outperform boys with decreased time spent in the NICU. The higher death rate in males continues throughout every age group of the lifespan. Because of these differences in birth and death rates, there are more boys than girls until age 18, where girls outnumber boys.

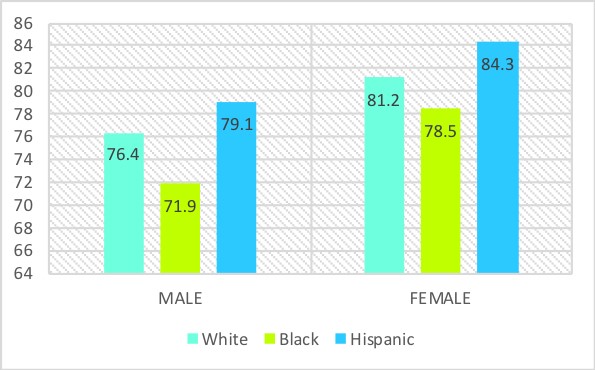

According to the 2017 CDC statistics, the life expectancy at birth was 78.6 years for the total US population. Since we know men do not live as long as women, and that there are differing mortality rates across ethnic groups, it’s important to identify the life expectancy of each gender with respect to ethnicity. The life expectancy at birth for White men was 76.4, and 81.2 for White women. Life expectancy for Black women was less than White women at 78.5, and Black men were significantly lower than White men at 71.9. Hispanic men and women had the highest life expectancy across both genders with Hispanic women living on average to age 84.3 and Hispanic men 79.1 (Arias & Xu, 2019). On average, women outlive men across ethnicities by approximately 5 years!

Figure 9.1. Life Expectancy by Gender and Ethnicity

There hasn’t always been a significant difference in life expectancy between men and women. When looking back to the 20th century, the life expectancy for White men in 1900 was age 47 and age 49 for women. Over the years, thanks to improved technology and advancement in medicine, as well as improved nutrition and elderly care, these rates steadily rose. The sex difference in mortality reached its largest difference in 1979 when women outlived men by nearly 7.8 years. This increased sex difference is largely related to a reduction in women’s mortality during childbirth and the increase in men’s mortality from heart disease and lung cancer (Minino et al., 2002).

The gap continues to vary between genders, with the smallest gap in recent years occurring in 2010. This narrowing is most likely related to the proportionate decrease in heart disease and cancer mortality among men than women, in addition to the increased incidence of lung cancer among women (Rieker & Bird, 2005). Although we will discuss in more detail later in this chapter, between 1979 and 1986, the incidence of lung cancer in men was 7%, however, in women it rose to 44% (Rodin & Ickovics, 1990)! These incidence rates are likely attributed to increased smoking in women, along with an increase of men quitting smoking (Waldron, 1995).

It should be noted that there are sex differences in life expectancy in other countries across the world that are likely dependent on the development of their country. Resources such as access to medical care, clean drinking water, and availability of food have all been linked to the life expectancy across nations. As observed in Table 9.1, the life expectancy varies significantly among 1st, 2nd, and 3rd world countries. Less developed countries have higher rates of infant mortality, pregnancy-related deaths, as well as poverty-related deaths thus contributing to the mortality rate (Murphy, 2003). Despite the lower life expectancies, the trend that women outlive men continues across throughout the world, regardless of the resources.

Table 9.1 Life Expectancy Among Countries by Gender

| Total | Male | Female | |

| 1st World | |||

| Hong Kong | 84.3 | 81.3 | 87.2 |

| Macau | 84.1 | 81.2 | 87.1 |

| Japan | 84.1 | 80.8 | 87.3 |

| Switzerland | 83.7 | 81.7 | 85.5 |

| Spain | 83.5 | 80.7 | 86.1 |

| 2nd World | |||

| Germany | 81.4 | 79.2 | 83.7 |

| Slovenia | 81.3 | 78.6 | 84.1 |

| Czech Republic | 79.1 | 76.2 | 81.9 |

| Albania | 78.7 | 76.7 | 80.8 |

| Croatia | 78.1 | 74.9 | 81.2 |

| 3rd World | |||

| Bangladesh | 73.2 | 71.6 | 75 |

| Cambodia | 69.8 | 67.5 | 71.8 |

| Senegal | 67.9 | 65.8 | 69.8 |

| Rwanda | 67.8 | 65.7 | 69.9 |

| Laos | 67.5 | 65.8 | 69.1 |

* 2019 World Population Review: http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/life-expectancy/

9.1.2. Causes of Death

The leading causes of death among men and women have changed over the last century due in large part to improvement in technology and advancement in medicine and medical care. In the 1900’s, the top three causes of death in the United States were pneumonia/influenza, tuberculosis, and diarrhea/enteritis (CDC, 2019), all of which are largely preventable today. Improvements in public health, sanitation, and medical treatments have led to dramatic declines in deaths from infectious diseases during the 20th century.

As you can see in Table 9.2, Heart Disease and Cancer have claimed the first and second leading causes of death in America, a rank they have held for over the last decade. In fact, together these two categories are responsible for 46% of deaths in the United States.

Table 9.2 Top 10 Leading Causes of Death in US

| Disease | Number of Deaths |

| Heart Disease | 647,457 |

| Cancer | 599,108 |

| Accidents | 169,936 |

| Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease | 160,201 |

| Stroke | 146,383 |

| Alzheimer’s Disease | 121,404 |

| Diabetes | 83,564 |

| Influenza and Pneumonia | 55,672 |

| Nephritis/Nephrotic syndrome/Nephrosis | 50,633 |

| Intentional Self-Harm | 47,173 |

* CDC Leading Cause of Death 2017 https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm

The etiology of these diseases are significantly more complicated than the etiology of infectious diseases that once held the top mortality spot. Environmental and behavioral factors, along with negative health habits such as smoking, poor diet, and alcohol consumption all contribute to the increased mortality rates across these disorders. Details of these behavioral factors will be discussed in more detail later in this module (Section 9.3).

As you will see, the death rate among all of these disorders is higher in males than females, with the only exception being Alzheimer’s disease, where women have a higher death rate than males. Similar to gender, leading causes of death are also influenced by ethnicity and age. Accidents, suicide, and homicide account for majority of the sex differences in mortality among younger individuals while, heart disease and cancer account for majority of the sex difference in mortality among older individuals. In fact, the leading cause of death for Hispanic men and women, White men and women, and Black women age 15-24 is accidents. The leading cause of death for Black men age 15-24 is homicide. Interestingly, although HIV is not in the top 10 causes of overall mortality, it is among the top 5 leading causes of death for Black men and women between ages 25-44 and Hispanic women between ages 35-44 (CDC, 2019).

9.1.3. Crime Statistics

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, men are more likely than women to commit violent crimes. Men are also more likely to be the victims of violent crimes with the exception of rape. Therefore, men are more likely to not only commit, but also be victims of assault, robbery, and homicide. In fact, 96% of homicide perpetrators and 79% of victims of homicide are men. Majority of male homicides are drug-related (90.5%) and gang-related (94.6%), whereas female homicides are accounted for more domestic homicides (63.7%) and sex-related homicides (81.7%; Homicide Trends in the United States). Women who are victims of homicide are ten times as likely to be killed by a male than female. In fact, the female perpetrator/female victim situation is extremely rare.

In watching the nightly news, one may think that most homicides within the US are at random when in fact, national surveys estimate that only 12% of victims were murdered by strangers, and 44% of victims of violent crimes actually knew their perpetrator (US Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2009). The perpetrator/victim relationship differs for men and women; women are more likely to be killed by someone they know.

9.2. Morbidity

Section Learning Objectives

- To understand factors that contribute to increase use of preventative care

- To understand gender specific factors that contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease

- To understand gender specific factors that contribute to an increased risk of various cancers

We have already talked a bit about how men are more likely to die than women, but what about gender differences in diagnosis of illnesses? Surprisingly, women are actually more likely to be diagnosed with an illness than men. There are many factors that contribute to this discrepancy, including preventative care and negative health behaviors (which we will discuss later). Additionally, because women do live longer than men, there is more time/opportunity for women to be diagnosed with an illness, particularly in their elderly age. Therefore, purpose of this section is to discuss the difference in morbidity rates and gender discrepancies among cardiovascular disease and cancer, seeing as these two disorders alone account for over half of all deaths in the United States.

9.2.1. Preventative Care

Before we discuss gender differences in diagnosis and death rates with regards to cardiovascular disease and cancer, it is important to discuss one factor that greatly contributes to not only diagnosis, but also prognosis: preventative care. In looking back at my grandparents, parents, and then even within my household, it is not surprising that women are more likely than men to seek out preventative care. From an early age, women are more conscious of health-related behaviors such as healthy eating habits and reduced sugar intake. Furthermore, women are more likely than men to engage in monthly self-exams and attend annual physicals (Courtenay et al., 2002). Women are also observed adhering to a prescribed medical regimen more closely than men and are more likely to follow-up with a physician’s instructions.

One factor that may contribute to the increase preventative care behaviors in women is reproductive issues. Women are encouraged to have yearly “well-women” visits that may include pap smears, breast exams/mammograms, and birth control evaluation. Additionally, women also have more medical appointments during and immediately following pregnancy, as well as older adults during menopause. Because men do not require similar medical care throughout their life, they may not have as well of an established resource as women.

What are the benefits of this established care? Well, if women are seen yearly for well check appointments, more serious medical conditions may be identified earlier than their male counterparts. Early diagnosis generally has a better prognosis. This may also explain why women tend to have a higher diagnosis rate of health disorders, yet a lower rate of mortality.

9.2.2. Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease refers to any medical condition that is related to heart and blood vessel disease. Most of these diseases are related to atherosclerosis, or the build-up of plaque in the walls of the arteries. Overtime, this build-up can narrow or even completely block the blood flow through the arteries, thus causing heart attacks or strokes.

A heart attack occurs when the blood flow to a part of the heart is blocked by a clot, causing reduced blood flow and death to that artery. While most people survive their first heart attack, medications and lifestyle changes are important to ensure a long, healthy life (American Heart Association, 2019).

An ischemic stroke, which is the most common type of stroke, occurs when a blood vessel that feeds the brain is blocked. Due to the blockage, some brain cells will begin to die, thus causing loss of functions controlled by that part of the brain. A hemorrhagic stroke, which is when the blood vessel within the brain bursts, often occurs by uncontrolled hypertension (i.e. high blood pressure). One can also experience a TIA or transient ischemic stroke which is caused by a temporary clot (American Heart Association, 2019); the effects of a TIA stroke are often minimal compared to a hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke.

The effects of a stroke depend on a variety of details, the main being the location in the brain that the vessel is blocked or bursts. For example, if the stroke occurs in the left-brain hemisphere, it could cause right side paralysis, speech/language problems, slow physical movement, and/or memory loss. A right-side stroke could result in left side paralysis, vision problems, fast behavioral movements, and/or memory loss. A stroke can also occur in various other brain regions and can be of various size. Both the location and size of the blood clot will impact the severity of the effects (American Stroke Association).

Congestive heart failure, another condition under the umbrella term of cardiovascular disease, occurs when the heart is not pumping blood as effectively as it should within one’s body. The implications of congestive heart failure are vast as the individual is not able to receive adequate supply of blood and oxygen throughout their body. Prior to developing congestive heart failure, one will likely experience abnormal heart rhythms, or arrhythmia. Arrhythmia’s can be categorized as a heart rate that is too slow (i.e. less than 60 beats per minute; bradycardia) or a heart rate that is too fast (i.e. more than 100 beats per minute; tachycardia; American Heart Association, 2019). Again, the effects of congestive heart failure can range from difficulty breathing after increased activity to death.

9.2.2.1. Prevalence rates. According to the American Heart Association, 121.5 million American adults have some form of cardiovascular disease. It is the leading cause of death of men of most racial and ethnic groups in the United States. In fact, the only ethnic group that it is not the leading cause of death in is Asian American/Pacific Islander men for which it is second to cancer. In women, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death for African American and White women; American Indian and Alaska natives have similar rates of cardiovascular disease and cancer; and Hispanic and Asian American/Pacific Islander women it is second to cancer.

Among cardiovascular disease in the United States, coronary heart disease was the leading cause of death (42.3%), followed by stroke (16.9%), high blood pressure (9.8%), heart failure (9.3%), diseases of the arteries (3.0%), and other cardiovascular diseases (17.7%; CDC, 2019). There are significant differences among gender and ethnicities of rates of coronary heart disease within the United States. More specifically, 7.7% of White men, 7.1% of Black men, and 5.9% of Hispanic men have coronary heart disease. Women follow a similar trend with 6.1% of White women, 6.5% of Black women, 6% of Hispanic women, and 3.2% of Asian women are diagnosed with coronary heart disease (CDC, 2019).

There is an observed difference in incidence rates of strokes between men and women. More specifically, men have a higher incidence of stroke until advanced age, with a higher incidence of stroke in women after age 85 (Rosamond et al., 2007). Despite the lower incidence rate in women until older age, more women than men die from stroke. Women also appear to have poorer functional outcome after strokes than men. One study found only 22.7% of women were fully recovered 6-months after an ischemic stroke compared to 26.7% of men. Women were also less likely to be discharged home after a stroke admission (40.9 vs 50.6%; Holroyd-Leduc, Kapral, Austin, & Tu, 2000). Researchers do caution that these studies did not account for age, and therefore, the poorer functional outcome may be related to age as women tend to have strokes older than men.

Similar to strokes, there is also an observed difference in age of first heart attack between men and women. More specifically, men tend to have heart attacks at younger ages than women with the average age at the first heart attack for men being 65.6 years and 72.0 years for females (Harvard Heart Letter, 2016). While this gender discrepancy is likely due to women living longer than men, thus having more heart attacks later in life, some also attribute the difference to the different heart attack symptoms between men and women. While both men and women primarily report chest pain as the primary discomfort prior to a heart attack, research indicates women are also more likely to identify symptoms such as nausea, dizziness, shortness of breath and fatigue more than chest pain. Because of these atypical symptoms, women may not seek medical care as immediately as men who are experiencing chest pain (Heart Attack Symptoms: Women vs. Men, 2019)

Women have a worse prognosis from heart disease compared to men (Berger et al., 2009). One explanation is that women are older when heart disease is diagnosed, as well as treated less aggressively than men. Most clinical trials that made important contributions to the advancement of care for heart disease have failed to include women in their research. The Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group (1983), one of the fundamental research studies on cardiovascular disease, included zero women in their 12,866 sample size. Because this study was critical in establishing diagnostic tests and treatment for cardiovascular disease, many argue that women are at a disadvantage in assessment and treatment as their physiology and symptom presentation was not included in the development of these tools.

9.2.3. Cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases that involves the growth of abnormal cells. There are more than 100 types of cancer that effect many different parts of the body. Although discussing every type of cancer is well beyond the scope of this course, it is important to identify the prevalence rates and death rates of the leading cancers specific to males and females.

According to the American Cancer Society’s statistics, the top 5 estimated new cases of cancer among all individuals in the US in 2019 include Breast (271,270), Lung and bronchus (228,150), Prostate (174,650), Colorectum (145,600), and Melanoma of the skin (96,480). Interestingly, the top 5 cancer deaths in 2019 were as followed: Lung and bronchus (142,670), Colorectum (51,020), Pancreas (45,750), Breast (42,260), and Liver (31,780). Despite the alarmingly high rate of breast cancer diagnoses, treatment and prognosis is generally good, thus the low percentage of death rates compared to incidence rates each year.

When examining gender differences, breast cancer is expected to account for 30% of female cancers and 14% of female deaths. While non-Hispanic White women are more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer than African-Americans, African-American women are more likely to die from breast cancer. Second to breast cancer is lung cancer, which is expected to account for 12% of female cancer cases and 25% of female cancer deaths. Finally, colon and rectal cancer accounts for 8% of all cancer cases and 8% of female cancer deaths (Hook, 2017).

In men, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer related deaths, causing more deaths than the next three leading causes (prostate, colorectal, and pancreatic cancer) combined. While prostate cancer is the number one diagnosed cancer in men, it is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in men. In fact, the 5-year survival rate for prostate cancer is 99%. Finally, colon and rectal cancer is both the third most frequently diagnosed and third cancer causing death in men.

9.2.3.1. Risk factors. Given the large number of cancer diagnoses and deaths every year, it is important that individuals identify risk factors in efforts to reduce the likelihood of developing cancer throughout their lifespan. Many of the behaviors we are about to discuss in section 9.3 are risk factors for many types of cancers. For example, active and passive tobacco use is the main risk factor for lung cancer, the number one cause of cancer mortality in the US. Additional environmental exposures such as arsenic, and radon, as well as outdoor air pollution, are also implicated in the rise of lung cancer diagnoses. Other factors such as poor dietary intake have also been linked to an elevated risk of lung cancer development.

Colon and rectal cancer is largely related to a family history of colon related illnesses such as colon polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, and colorectal cancer itself. Additionally, negative behaviors such as smoking, increased alcohol consumption, obesity, and eating large amounts of red and processed meats also places an individual at risk for developing colon cancer.

Finally, reproductive cancers- cancers of the reproductive systems such as breast cancer and prostate cancer- have a strong genetic component. For example, the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are found in some variations of breast cancer. In fact, women with these genetic mutations are also at greater risk for other reproductive cancers such as ovarian cancer. Some studies have also linked the BRCA mutations to prostate cancer in men, however, additional research is needed to fully understand this relationship. Additional risk factors for both breast and prostate cancer include being over the age of 50, increased alcohol consumption, and smoking (American Cancer Society, 2019).

9.3. Health Behaviors

Section Learning Objectives

- To understand how exercise may have a positive effect on an individual’s health

- To understand how obesity negatively impacts one’s overall health and contributes to an increased morbidity rate

- To understand how alcohol negatively impacts one’s overall health and contributes to an increased morbidity rate

- To understand how tobacco negatively impacts one’s overall health and contributes to an increased morbidity rate

- To understand how drugs negatively impacts one’s overall health and contributes to an increased morbidity rate

We just discussed a few of the most common types of illnesses diagnosed in the United States in both men and women. While we do not know exactly why some people develop some disorders and others do not, we do know there are some factors that have a positive impact (i.e. reducing the likelihood of developing a disorder) and others that have a negative impact (i.e. increase the likelihood of developing a disorder) on one’s overall health. Therefore, the focus of this section is to identify these factors that contribute to an increased morbidity rate. Additionally, we will discuss the gender discrepancies observed among these contributing factors

9.3.1. Exercise

Our first factor, exercise, is a positive health behavior that has shown to reduce the rates of mortality and morbidity. More specifically, increased activity level is associated with reduced heart disease, hypertension, colon cancer, Type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, and depression. Conversely, reduced physical activity is associated with obesity and subsequent health complications (See section 9.3.2).

According to the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, the recommended guidelines for physical activity include 30-minutes, five days a week of moderate-intensity exercise such as walking, bicycling, gardening, or any other activities that produce a small increase in breathing or heart rate. It is estimated that 21.9% of adults met this criteria last year with 26.9% of adults not engaging in physical activity at all. This statistic varies significantly between ethnic groups. More specifically, 25% of non-Hispanic White adults, 20.8% of Non-Hispanic Black adults, 16.6% Hispanic adults, and 17% Asian adults reported meeting the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans within the last year (Center for Disease Control, 2019).

As we will discuss in the next section, childhood obesity has been on the rise, which has been attributed to a decrease in childhood physical activity and an increase in sedentary activities such as television watching and computer game playing. In a study by the CDC (2010a) an estimated 46% of high school boys and 28% of high school girls said they had been physically active for five of the past seven days. The rates of girls who reported not engaging in any physical activity over the past seven days was higher (30%) than boys (17%) suggesting the gender gap in exercise begins from an early age.

The gender gap in physical activity has long been attributed to gender specific behaviors. More specifically, boys are more likely to participate in sports, whereas girls are more likely to be involved in individual, noncompetitive sports such as dance. In fact, only 25% of girls participate in sports compared to 43% of boys. Despite these statistics, girls’ involvement in sports throughout the lifespan have been increasing over the past decade (CDC, 2010a).

9.3.1.1. Effects of exercise. Several longitudinal studies have examined the relationship between physical activity and disease incidence. Findings suggest strong evidence for a relationship between amounts of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and cardiovascular disease mortality. The risk of a cardiovascular event decreased with increased exposure of physical activity up to at least three to five times per week. When exploring the studies further, Sattelmair and colleagues (2011) reported a 14% reduction in developing coronary heart disease for those reporting moderate activity level compared to those with no leisure-time physical activity. Additionally, rates of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, as well as coronary heart disease were significantly reduced for individuals participating in moderate physical activity level (Kyu et al., 2016). Interestingly enough, none of these studies reported a sex difference in findings suggesting that both men and women benefit equally from an increase in physical activity level.

Researchers have also explored the relationship between physical activity level and incidence of cancer. As one can imagine, it’s difficult to determine a relationship between physical activity and cancer in the general sense, however, strong relationships were found for specific cancers. More specifically, greater amounts of physical activity were associated with a reduced risk of developing bladder (Keimling, Behrens, Schmid, Jochem & Leitzmann, 2014), colon, gastric (Liu et al., 2016), pancreatic (Farris et al., 2015) and lung cancer (Moore et al., 2016). While most had similar effects between men and women, physical activity level appeared to have a stronger protective factor for women and lung cancer incidence rates.

The relationship between increased physical activity level and reduced incidence of breast cancer was also found, however, there appears to be a few factors impacting this relationship. More specifically, menopausal status appears to moderate the relationship between physical activity level and menopause status suggesting that physical activity has a smaller effect on postmenopausal women’s likelihood of developing breast cancer. This finding is not surprising given that postmenopausal women are already at an increased risk to develop breast cancer in general. Additionally, histology of breast cancer is another factor that impacts the relationship between physical activity and breast cancer incidence rate. Breast cancers that have a strong genetic histology are less likely to be impacted by physical activity level (Wu et al., 2013).

It is obvious from these studies that any amount of physical activity has greater benefit than no physical activity at all, although an increase in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity does appear to increase health benefits, particularly related to cardiovascular disease. It is important to note that physical activity also has an inverse relationship with mental health disorders as an increase in physical activity level is associated with a decrease in mood and anxiety disorders.

9.3.2. Obesity

While exercise is shown to improve cardiovascular function and overall physical health, obesity, or being excessively overweight, can have negative health implications. More specifically, obesity is a significant risk factor for mortality among a host of medical issues such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, and some cancers. Before we discuss the health implications of obesity, it is important that we identity how an individual is categorized as obese.

The most common way to identify if an individual is obese is through the body mass index (BMI). The formula for BMI is one’s weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. For non-metric users, it can also be calculated by pounds divided by inches squared and then multiplied by 703. This number can then be compared to the National Institute of Health’s standards (see table 9.3). There are some arguments against the use of the BMI to determine obesity as it does not account for difference in muscle and fat density; however, it continues to remain the most common standard for assessing obesity in the US.

| Table 9.3 NIH BMI Categories | |

| Underweight | < 18.5 |

| Normal | 18.5-24.9 |

| Overweight | 25-29.9 |

| Obese | >30 |

It is also important to note that obesity often looks different in men and women. Android obesity, more commonly known as the “apple” shape, is more commonly seen in men. These individuals tend to carry a lot of their weight in their abdomen. According to the android obesity measure, men with a waist to hip ratio greater than one and women with a waist to hip ratio greater than 0.8 are at significant risk for obesity related health problems. On the contrary, gynoid obesity, which is more commonly seen in women, is more commonly described as “pear” shape. These individuals tend to have more weight in their hip region, thus the description of a pear. Individuals with a physical shape consistent with android obesity are at greater health risks than those with gynoid obesity. This is true for both men and women, however, research indicates that obesity has a stronger relationship to mortality in men when individuals are under age 45, and a stronger relationship to mortality in women when individuals are over the age of 45 (Lean, 2000).

9.3.2.1. Prevalence rates. According to the CDC, the prevalence of obesity among US adults was 39.8%; however, the percentage of obese adults aged 40-59 (42.8%) was higher than among adults aged 20-39 (35.7%). While men are more likely to be overweight than women, women are more likely to be obese. This was also observed in the CDC statistics among individuals in the 40-59 age group (40.8% men; 44.7% women) and the 20-39 age group (34.8% men; 36.5% women). Overweight and obese men are less likely than women to perceive their weight to be a problem (Gregory et al., 2008).

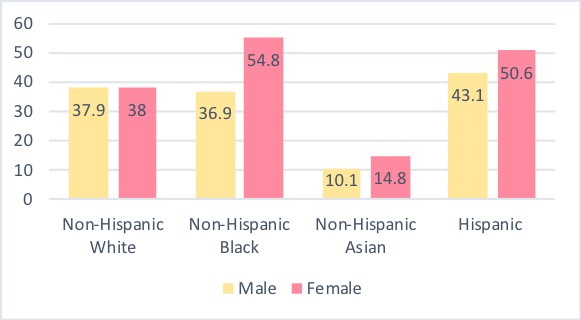

There also appears to be a significant difference in obesity rates among different ethnic groups. Non-Hispanic Asian adults had the lowest (12.7%) rate of obesity compared to all other ethnic groups. Hispanic (47%) and non-Hispanic black (46.8%) adults had the higher prevalence rates of obesity than non-Hispanic white adults (37.9%). The gender difference among ethnicities reflects that of the general public with women having a higher rate of obesity than men (see Figure 9.2 below). Views of obesity differ across gender and races which may explain some of the difference in obesity among ethnic groups and gender. White women report more body dissatisfaction than Black and Hispanic women (Grabe & Hyde, 2006); however, women of all ethnicities report wishing they were thinner but the desire occurs at a lower BMI for White girls than Black and Hispanic girls (Fitzgibbon, Blackman & Avellone, 2000).

Figure 9.2 Obesity Rates among Gender and Ethnicity

Childhood obesity has also risen over the last few decades. The prevalence rates of obesity among US youth was 18.5% (CDC). The obesity rates were highest among adolescents (20.6%), followed by school-age children (18.5%) and preschool-age children (13.9%). Unlike the gender discrepancy in adulthood, childhood obesity does not differ significantly between adolescent boys and girls (20.2% and 20.9%, respectively) or school age boys and girls (20.4% and 16.3%, respectively). It should be noted that obesity in children is defined differently than that in adults. More specifically, obesity in children is categorized as a BMI at or above the 95th percentile for one’s age and sex.

While it is obvious that obesity rates differ between genders, a discrepancy is also found by income and educational level. More specifically, obesity rates appear to increase as income level decreases, with individuals earning greater than 350% above the poverty level having significantly lower rates of obesity than those making less than 350% above the poverty level. Similarly, obesity rates also appear to increase as education level decreases; college graduates report significantly lower rates of obesity than individuals with some college and those who were high school graduates or less. Researchers attribute the increase obesity rates in lower SES and uneducated families to poor diets and less exercise. Obesity is not related to SES across all ethnic groups, as obesity is related to higher SES in white men, white women, and black women; lower SES among Black and Hispanic men; and unrelated to SES among Hispanic women (CDC, 2019).

9.3.2.2. Effects of obesity. Individuals who are overweight or obese are at an increased risk for many serious health diseases and health conditions. In general, individuals with obesity have a higher mortality rate than individuals within a normal weight range. This is likely related to the increased risk of cardiovascular disease in overweight individuals. More specifically, individuals who are obese are more likely to have high blood pressure as a result of the increased body fat tissue requiring additional oxygen and nutrients. Similarly, atherosclerosis is present 10 times more often in obese individuals than those of normal weight. Coronary heart disease is also another risk factor due to the increased fatty deposits build up in arteries. The narrowed arteries and reduced blood flow also make obese individuals at greater risk for having a heart attack or stroke (Lean, 2000).

Second to cardiovascular disease is diabetes. Type 2 diabetes is usually diagnosed in adults secondary to obesity; however, with the rise of childhood obesity, physicians are diagnosing Type 2 diabetes more frequently in children. Type 2 diabetes involves resistance to insulin, the hormone that regulates blood sugar. Due to the increased weight, the pancreas makes extra insulin to regulate blood sugar, however, overtime, the pancreas cannot keep up, thus sugar builds up in the blood stream. The effects of uncontrolled Type 2 diabetes can cause significant damage to one’s kidneys, eyes, and nerves, thus effecting your entire body. If left uncontrolled for a significant time period, it can lead to death (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019).

Overweight individuals are also at an increased risk for various types of cancers. More specifically, overweight women are more likely to be diagnosed with breast, colon, gallbladder, and uterine cancer than their normal weight peers. Men are also at an increased risk for colon cancer, as well as prostate cancer (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019).

Finally, psychosocial effects of obesity across the lifespan are often observed, particularly in a culture where physical attractiveness is measured by body size. Overweight individuals are at risk for various mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety. The link between obesity and depression is difficult to define as it could be related to the neuroendocrine changes associated with stress and depression, which may cause metabolic chances that predispose individuals to obesity (Vidya, 2006). Overweight children and adolescents are at an increased risk for bullying at school. Several studies have found that obese adolescents are more isolated and marginalized, and experience more teasing and bullying (Faulkner et al., 2001; Janssen et al., 2004; Strauss & Pollack, 2003).

9.3.3. Alcohol

Alcohol, unlike other substances, can have positive health benefits in moderation. For example, moderate alcohol consumption in both men and women may reduce the risk of heart disease and stroke. Although there is some support for this risk reduction, it may be offset at higher rates of alcohol use due to increased risk of death from other types of heart disease and cancer (Health Risks and Benefits of Alcohol Consumption, 2000). With that said, alcohol in large quantities is detrimental to one’s health as evidenced by nearly 3 million deaths every year related to the harmful use of alcohol.

While the DSM-5 defines Alcohol Use Disorder as recurrent alcohol use that also impacts one’s ability to function in daily life, it is important to acknowledge that one does not need to meet diagnostic criteria for Alcohol Use Disorder to develop significant health consequences. With that said, there are “categories” established by researchers to help identify consumption rates of alcohol among individuals. Per the Center for Disease Control, binge drinking, which is the most common form of excessive drinking, can be defined as four or more drinks during a single occasion for women, and five or more drinks for men. Heavy drinking is defined as consuming 8 or more drinks per week for women and 15 or more drinks per week for men. Finally, moderate drinking is defined as up to one drink per day for women and up to two drinks per day for men.

9.3.3.1. Prevalence rates. Men are more likely to engage in binge and heavy drinking than women. An estimate from the CDC suggests that 23% of men binge drink 5 times a month, which is nearly two times more likely that women (12%). A study conducted by Wilsnack and colleagues (2000) found that men were more likely to drink alcohol more frequently, consume higher amounts of alcohol at one time, and had more episodes of heaving drinking. Because of this increase in consumption, men were also more likely to suffer adverse consequences of drinking compared to women. These findings have been replicated in college age students where men also report drinking more alcohol, as well as having more alcohol-related problems than women (Harrell & Karim, 2008); however, when examining alcohol related behaviors in high school students, rates of frequency and consumption are similar among both males and females (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010a).

9.3.3.2. Gender differences. While some attribute the gender difference in alcohol consumption to societal attitudes being more accepting of men to consume larger amounts of alcohol than women, others argue this is not applicable to the current generation due to the smaller discrepancy between genders over the past few years. Despite the narrowing differences, there does appear to be some social expectations on women to not consume large quantities of alcohol as it may interfere with her abilities to care for her family (Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2006).

Another more supported explanation for the gender difference in both effects and consumption of alcohol is due to differences in physiology. It takes proportionally less alcohol to have the same effect on a woman as a man, even when controlling for body weight. More specifically, if a man and a woman of similar height and weight consumed the same amount of alcohol, the woman would have a higher blood alcohol level. This difference is due in large part to the greater ratio of fat to water in a woman’s body; men have greater water available within their body to dilute the alcohol. Additionally, men have more metabolizing enzymes in their stomach, which also helps reduce the amount of alcohol quicker, thus reducing the effects of consumption. Because of these physiological differences, women are more vulnerable to long-term negative health consequences than men (Duke University, 2019).

9.3.3.3. Effects of alcohol. Alcohol consumption in excess (i.e. binge drinking) can have immediate health risks such as increased likelihood of injuries from accidents such as automobiles, falls, drownings, and burns. Additionally, individuals who are severely inebriated are also at risk for violence, particularly sexual assault and intimate partner violence. This also coincides with increased risky sexual behaviors that can result in unintended pregnancy and/or sexually transmitted diseases.

Women who drink excessively while pregnant also have an increased risk in miscarriage and stillbirth. Infants born to mothers who drank excessively during pregnancy are at risk for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD). FASD causes a range of problems including abnormal appearance, small head size, poor coordination, low intelligence, behavioral problems, and hearing and/or vision problems.

Excessive alcohol use is also attributed to an increase cancer rate. More specifically, an increased rate of cancer in the mouth, throat, esophagus, liver, and colon are observed. While excessive alcohol consumption alone raises the risk of mouth, throat, and esophageal cancer, drinking and smoking together raises the risk even higher. It is believed that alcohol limits the repair of the cells in these regions, thus allowing chemicals in tobacco to permeate the cell membrane more easily (Health Risks and Benefits of Alcohol Consumption, 2000).

Colon and rectal cancer have also been linked with a higher risk of cancer. Although the relationship between alcohol consumption and colon/rectal cancer is stronger in men, the link for an increased risk is found in both men and women. Finally, breast cancer is also found to have a link to alcohol consumption. Women who have only a few drinks a week appear to have a greater likelihood of developing breast cancer than those who do not drink at all (Health Risks and Benefits of Alcohol Consumption, 2000).

Given that the liver filters the body of harsh chemicals, it is not surprising that individuals who consume large amounts of alcohol also are at risk for liver cancer as well as liver disease. Cirrhosis, or scarring of the liver, is a common result of chronic alcoholism. Liver damage from cirrhosis cannot be undone, however, if it is diagnosed early, the initial scaring can be treated thus preventing further damage.

Additional long-term effects include cardiovascular disorders such as high blood pressure, heart disease, and stroke. More specifically, heavy drinking is related to an increased risk of having either a hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke. Like mentioned above, minimal alcohol use may actually reduce the risk of stroke, however, this appears to be more protective for men than women. In fact, the risk of having a stroke increases in women when women drink more than one alcoholic beverage a day (Thun et al., 1997).

Individuals with an alcohol abuse problem are also likely to suffer from a comorbid mental health disorder. In fact, approximately one-third of individuals with an alcohol use disorder also met criteria for at least one anxiety or mood disorder in the past 12 months. According to one study, 17% of individuals with an alcohol abuse diagnosis also met criteria for a mood disorder, 16% met criteria for an anxiety disorder, and 35% met criteria for another substance abuse disorder. More specifically, Major Depressive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder were among the specific disorders with the highest comorbidity rate (Burns, Teesson, Lynskey, 2001).

9.3.4. Tobacco

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, smoking is the single most preventable cause of death. Tobacco accounts for one in five deaths and 30% of all cancer-related deaths including lung, lip, oral, esophagus, pancreas, and kidney. In addition to cancer, smoking has also been linked to heart disease, particularly in women (Tan, Gast, & van der Schouw, 2010). Fortunately, when individuals quit smoking, their risk of developing heart disease decreases dramatically. In fact, within five years of quitting, heart disease rates are similar to that of a nonsmoker.

9.3.4.1. Prevalence rates. According to the CDC’s 2017 survey, 14% of all adults were smokers: 15.8% of men and 12.2% of women. This rate is significantly lower than the 23.2% prevalence rate of cigarette smoking in 2000. Researchers suspect that the prevalence rate of smoking will decline through 2030. The reduction in smoking is attributed to an increase tax on cigarettes as well as the increased health warnings of the effects of smoking.

It is also important to mention children and adolescent smoking behaviors as nearly 90% of smokers begin to smoke during adolescence (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010). Recent statistics estimate less than 1% of middle school students and 5.4% of high school students smoke cigarettes. These numbers have declined drastically since they peaked in 1997 with 9% of middle school and 25% of high school students reporting smoking cigarettes. Ethnic discrepancies are also present as white teens are more likely to smoke than their black or Hispanic peers (Kann et al., 2018).

9.3.4.2. Effects of tobacco. It’s hard to miss advertisements aimed at identifying the negative health effects of smoking. Most involve an older individual with a raspy voice talking about how they now require oxygen to complete daily activities; others showcase an individual missing part of their face or neck due to surgery to remove cancerous tumors. Given all of this public information, it should not come as a surprise that smoking has a strong relationship with lung cancer. In fact, smoking causes about 90% of all lung cancer deaths (US Department of Health and Human Services). Men who smoke are 25 times more likely to be diagnosed with lung cancer than their nonsmoking peers; women smokers are 25.7 times more likely to be diagnosed with lung cancer (CDC). While the risk of developing lung cancer decreases once an individual quits, they still have a higher risk of developing lung cancer than nonsmokers.

In addition to an increased likelihood of developing lung cancer, individuals who smoke are at an increased risk for diseases caused by damage to the airways and the alveoli (found in the lungs). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is an umbrella term used to describe a variety of lung diseases such as emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and refractory asthma. Individuals who smoke are 13 times more likely to die from COPD than nonsmokers (US Department of Health and Human Services). These statistics are even higher for individuals who have a diagnosis of asthma, smoking can trigger attacks or make them more severe.

Individuals who smoke are also at a greater risk for diseases that affect the heart and blood vessels, a relationship that appears to be stronger for women than men (Tan, Gast, & van der Schouw, 2010). Smoking has been linked to strokes and coronary heart disease, even in individuals who smoke irregularly. This increased heart disease is likely due to damages to blood vessels which cause them to thicken and grow narrower. Narrowed blood vessels make the heart beat faster which causes blood pressure to increase. Additionally, the narrowed blood vessel also increases an individual’s chance of developing a blood clot or blockage, thus increasing chances of stoke.

9.3.5. Drugs

For the purpose of this text, drug use refers to the use of illicit drugs which can be defined as any illegal drugs, including marijuana (according to federal law), as well as the misuse of prescription drugs. In 2013, there was an estimated 24.6 million Americans who reported using an illicit drug within the past year. This number has increased 8.3% since the 2002 data collection, which is likely due to the increase in marijuana use among both men and women across age groups. In fact, the use of all other drugs has stabilized or declined over the past decade (National Institute of Drug Abuse, 2019).

When examining gender differences, men are more likely to have higher rates of illicit drug use or dependence than women, however, women are equally as likely as men to develop a substance use disorder (Anthony, Warner, & Kessler, 1994). Studies also suggest that despite the lower prevalence rate of drug use in women, they may be more susceptible to cravings and relapse, two important factors in the maintenance of addiction (Kennedy, Epstein, Phillips, & Preston, 2013; Kippin et al., 2005; Robbins, Ehrman, Childress, & O’Brien, 1999). These gender differences are likely attributed to different physiological responses to various drugs in men and women.

Given that illicit drug use is more common in men, it should not be surprising that men also report more ER visits or overdose deaths than women. In 2017, there were just over 70,000 drug overdose deaths, with men accounting for 66% of these deaths. Opioids are the main driving force in these overdose deaths (National Institute of Drug Abuse, 2019).

9.3.5.1. Illicit drug gender discrepancies. Marijuana. Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug among drug users in the United States. Similar to other drugs that we will discuss, males have a higher rate of marijuana use than females. Researchers argue that this gender difference may be related to differences in physiological response to the drug. More specifically, male users appear to have a greater marijuana-induced high (Haney, 2007), whereas women report impairment in spatial memory (Makela et al., 2006). These findings are also supported in animal studies that show female rats are more sensitive to the rewarding, pain-relieving, and activity altering effects of THC (the main active ingredient of marijuana; Craft, Wakley, Tsutsui & Laggart, 2012; Fattore et al., 2007; Tseng & Craft, 2001).

Stimulants. Stimulants refer to cocaine and methamphetamine. Again, research indicates that women may be more vulnerable to the reinforcing effects of stimulants due to increased estrogen receptors compared to men. Animal studies indicate that females are quicker to start taking cocaine and consume larger quantities of cocaine than males. Despite what appears to be an increased addictive physiology, female cocaine users are less likely than males to display abnormal blood flow in the brain’s frontal region (Brecht, O’Brien, von Mayrhauser & Anglin, 2004).

In addition to physiological differences, men and women also report differences behind the reason why they engage in stimulant drug use. For women, stimulant use is generally related to a desire to increase energy and decrease exhaustion in work, home, and family responsibilities. Additionally, stimulant use is also cited as a means to lose weight- something that is reported more often in women than men (Cretzmeyer et al., 2002). Men report using stimulants more often than women as a means to “experiment,” as well as replace another drug that may not be available at a given time.

MDMA. MDMA, or more commonly known drugs such as Ecstasy and Molly, are known to produce stronger hallucinatory effects in women compared to men. Despite these differences, men show higher MDMA-induced blood pressure. Research studies indicate that behavioral reactions during drug withdrawal of MDMA substances such as depression and aggression are similar in both men and women. With that said, there are some physiological differences in response to MDMA substances that increase females’ likelihood of death than males. More specifically, MDMA interferes with the body’s ability to eliminate water and decrease sodium levels in the blood, thus causing users to consume large amounts of fluid. In some cases, the increased fluid consumption can lead to increased water in between cells which can cause swelling of the brain and eventually death. Females appear to be more susceptible of this increase of fluid between cells as almost all of the reported cases of death from this biological change is in females (Campbell & Rosner, 2008; Moritz, Kalantar-Zadeh & Avus, 2013).

Heroin. Men are more likely than women to not only use heroin, but also consume larger amounts and for longer periods of time than women. Furthermore, men are more likely to use heroin intravenously than women (Powis, Griffiths, Gossop & Strng, 1996). Women who do choose to inject heroin are at a greater risk for overdose death than men. While the exact cause for this is unknown, researchers suggest it may be related to the relationship between intravenous drug use and prescription drugs as women who inject heroin are also more likely to use prescription drugs (Giersing & Bretteville-Jensen, 2014).

Prescription Drugs. Nearly 2.5% of Americans report using prescription drugs non-medically in the last month. These drugs include pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, and sedatives. Prescription drug use is the only drug category in which women report higher use than men. Researchers suggest the difference in prescription drug use is due to the lower sensitivity and higher reports of chronic pain in women than men (Gerdle et al., 2008). Studies have also reported that women are more likely to take a prescription opioid without a prescription to cope with pain, even when men and women report similar levels of pain. Furthermore, women are more likely to self-medicate and misuse prescription opioids for other issues such as anxiety (Ailes et al., 2008).

Despite the higher use of prescription drug use in women, men are more likely to die from a fatal opioid overdose. With that said, deaths from prescription opioid overdoses increased more rapidly for women than men, with women between the ages of 45 and 54 more likely to die from a prescription opioid overdose than any other age group (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019).

9.3.5.2. Health effects related to drug use. Individuals who engage in drug use are at risk for other high-risk behaviors associated with drug use that place them at risk for contracting or transmitting diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), or hepatitis (Drug Facts, 2019). Drug addiction has been strongly linked with HIV/AIDS since the disease was first identified. In fact, it is estimated that one in 10 HIV diagnoses occur among people who inject drugs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017a). A recent study from the CDC (2017) reported nearly 20% of HIV cases among men, and 21% of HIV cases among women, were attributed to intravenous drug use (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017b). This is of particular concern for women as there is a risk of disease transmission to their child during pregnancy and birth, as well as through breastmilk (although this is extremely rare).

Hepatitis, or the inflammation of liver, is caused by a family of viruses: A, B, C, D, and E. Intravenous drug use has a strong link to Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C. Without treatment, Hepatitis can lead to cirrhosis and loss of liver function. Furthermore, it can also lead to liver cancer. In fact, Hepatitis B and C are the major risk factors for liver cancer in the US (Ly et al., 2012).

9.4. Environmental Factors and Physical Health

Section Learning Objectives

- To learn the impact of marriage on one’s physical and mental well-being.

- To learn how parenthood might affect one’s mental health

- To identify the moderators that account for the variability of mental health issues in parenthood

- To understand the gender differences in the relationship between bereavement and physical and mental health

We have already discussed behavioral factors that contribute to one’s physical well-being, but what about environmental factors? We know that stress in one’s environment can lead to an increased likelihood of engaging in negative behaviors such as poor nutrition, increase use of substances (i.e. smoking and alcohol consumption), and a reduced likelihood of engaging in physical activity. Therefore, the purpose of this section is to identify some of these environmental factors that may negatively contribute to one’s overall well-being, as well as discuss any gender discrepancies observed within these factors.

9.4.1. Marriage/Relationships

Research continually supports that marriage is a resource that promotes and protects against health disorders. While marital status does not predict mortality, never married individuals have a 158% increase in mortality compared to married individuals. Interestingly, this difference was larger for men than women, with unmarried men being at risk for increased mortality rates of infection and accidents (Kaplan & Kronick, 2006). Additional studies implied that not being married placed men at an increased risk for death compared to unmarried women.

When assessing health factors, married individuals have less reported depression than unmarried individuals. The difference between married and unmarried depression rates are greater in men than women. Married individuals are also less likely to experience a stroke compared to unmarried individuals. Similarly, this relationship is also stronger in men than women (Maselko et al., 2009). It would appear from multiple sources and studies that marriage offers more benefits for men than women.

In efforts to identify specific factors that contribute to the benefits of marriage, researchers examined health disparities among married, unmarried, and unmarried but cohabitating individuals. Overall, studies have found that cohabitation does not offer the same amount of support as marriage. For example, cohabitating individuals report more depression than married individuals, but less than widowed or divorced individuals (Brown, Bulanda, & Lee, 2005). This would imply that there are some benefits to cohabitating, although it does not appear as beneficial as marriage.

Research on same-sex relationships is more limited than heterosexual couples, however, Weinke and Hill (2009) compared happiness of heterosexual married, cohabitating, single, and “other” with same-sex individuals who were cohabitating and single. Findings indicated that heterosexual married individuals were the happiest, followed by heterosexual cohabitating and then same-sex partners cohabitating. Heterosexual single and “other” were nearly the same in men and women, and same-sex single men and women reported the lowest levels of happiness. While there are obviously external factors that may contribute to these individual’s happiness, it is worth noting that heterosexual married individuals reported highest levels of happiness, whereas same-sex single individuals were the least happy.

9.4.1.1 Dissolution of marriage. Just as it is important to discuss the impact of marriage on health behaviors, it’s also important to discuss the impact of a dissolution of a marriage through either divorce (death is covered in section 9.4.3). While marriage appears to provide a protective factor on heath and psychological well-being, separation/divorce may be related to a decline in physical and mental health. Molloy and colleagues (2009) found that individuals who were separated/divorced had reported worse overall health than their married counterparts. These marital transitions are correlated with adverse health effects that appear to impact men more negatively than women. More specifically, Hughes and Waite (2009) found that divorce was related to an increase in mortality and psychological distress for men, but not women. Despite the decline in health for divorced or separated men, unmarried men had worse health outcomes than men who experienced a relationship status change suggesting that marriage, even if not for the remainder of their life, provides some health benefits (Hughes & Waite, 2009).

Researchers argue that it’s important to acknowledge that gender differences in response to the end of a marriage impact men and women differently, most noticeably by changes in roles within the household. Women tend to make a greater economical shift post-divorce, thus it is not surprising that women report a greater financial strain. In fact, men’s income decreases roughly 10% post-divorce compared to a 33% decrease in women’s income (Avellar & Smock, 2005). However, men report a significant strain in social support compared to women. This shift is often explained by the fact that wives are typically married men’s primary source of support, thus, losing this support after their divorce.

Another argument as to why men appear to have more adverse health effects post dissolution of marriage is due to initiation of break-up. Women are more likely than men to initiate a divorce. This is not surprising as women also report less satisfaction than men within a marriage (Bodenmann, Ledermann, & Bradbury, 2007). Therefore, one might assume that because women are more dissatisfied, they may be more aware of problems within the relationship, thus more adjusted by the time the marriage ends.

9.4.1.2. Quality of marital relationship. It is important that we also assess the impact of the quality of a marital relationship as we all know not all marriages (or relationships) are the same. Some relationships offer high levels of support, whereas others are more toxic than helpful. Research on the impact of the quality of a marriage suggests unhappily married men and women are more depressed than their unmarried counterparts (O’Leary, Christian, & Mendell, 1994). Furthermore, married people who reported high levels of dissatisfaction on how their spouse treated them also reported more distress than unmarried individuals (Hagedoorn et al., 2006). Additionally, unhappily married people displayed increased blood pressure compared to both happily married and single individuals (Holt-Lunstad, Birmingham, & Jones, 2008). These findings suggest that researchers need to take into consideration the quality of the marriage when assessing the impact marriage has on the psychological and health of individuals.

9.4.1.3. Factors explaining gender differences in marriage. There are many factors that may explain the differing effect marriage has on men and women’s health behaviors. The first is social support. Married men and women report higher levels of social support than unmarried individuals, however, husbands receive more social support from their wives than wives receive from their husbands (Goldzweig et al., 2009). Women may make up for this lack of support by establishing a social support network from friends. This additional network may also explain why men who live alone become more depressed than women living alone due to the lack of external support.

Health behaviors is another factor that also appears to benefit married men. More specifically, married men are more likely to utilize preventative care and take care of themselves when sick than unmarried men (Markey et al., 2005). Interestingly, unmarried men also report drinking more alcohol than married men while there does not appear to be a difference in drinking behavior between married and unmarried women. With regards to smoking behaviors, unmarried men and women reportedly smoke more than married men and women (Molloy et al., 2009). From these findings, it appears that men take more responsibility for their health in married relationships than unmarried relationships which may also explain married men’s overall better health status.

Finally, marital satisfaction has also been identified as a potential factor that may impact a married individual’s health status. Research continually identifies that women are more dissatisfied in their marriage than men. Women report more problems in marriage, more negative feelings about marriage, and more frequent thoughts on divorce (Kurdeck, 2005). Some argue that women become more dissatisfied with the marriage due to gender roles, particularly after the couple has children. Many women take on majority of the child-care responsibility either in addition to their employment, or, leave their employment to take care of the children full-time. In either case, the woman’s role in the marriage is more affected than the man’s once the couple has children.

9.4.2. Parenting

As previously discussed, gender roles have been identified as one of the main factors contributing to the differences in health outcomes between genders. Although we have seen an increase in men’s involvement in parenting, women still remain the primary care takers of children, even when working outside of the home.

It is also important to identify that due to an increased divorce rate, as well as an increase in nonmarried women having children, there has been a significant decrease in the number of two parent households. According to the US Census Bureau, 69% of children under age 18 live in a 2-parent household. This number has continually dropped since 1960 when 88% of children lived in a 2-parent household. The current statistics for children living with a single parent has also risen over the years, with 23% of children currently living with a single mother (United States Census Bureau, 2019).

Women in general are not having as many children as they have in the past. Not only has the number of women choosing not to have children increase over the past decade, so has the total number of children born to a woman. The average number of kids in the home has decreased to an average of 1.9 kids in a US family. The average number of children in the home has hovered just under 2 since 1977 (Statista, 2019). It is suspected that the decrease in number of children is due in large part to improved contraceptives, as well as an increase in women in the workforce. In fact, 62% of children have mothers working in the workforce. Despite this increase in women working, findings suggest that parents spend as much time with their kids as they did 20 years ago (Galinsky et al., 2009). The stability of this statistic is attributed to an increase in the ability to telework!

9.4.2.1. Effects of parenthood on health. The research on the effects of parenthood on one’s mental and physical health are completely mixed. Some argue that parental status is unrelated to psychological well-being (Bond, Galinsky, & Swanberg, 1998). In fact, several studies cite no relationship between parenthood and depressive symptoms in a wide range of different groups of parents (e.g. single parents, empty nesters; Evenson & Simon, 2005). On the flip side, other studies have found an elevated rate of depression in mothers, but not fathers, and that single mothers may be the most at risk (Bebbington et al., 1998; Targosz et al., 2003). Other studies have found single fathers are more at risk for developing an alcohol abuse problem than married fathers (Evenson & Simon, 2005)

The problem with studies assessing the relationship between parenthood and mental health is there are a host of moderating variables that impact this relationship. Take for example the increased risk for single mothers to develop depression. Is this increased risk truly due to being a parent? Or is it related to being a single parent? What about the financial stress of being a single parent? Lack of social support? This unfortunately is a common issue among research in this domain. Other moderators such as employment status, age of parent, and health of child are among the most commonly overlooked moderators. For example, prevalence rate for depression among single and supported mothers differed in the age group of 25 to 50 years. Women who have full-time employment outside of the home report higher impairment than women who work part-time (Bebbington, 1996). Finally, parents of children with a significant disability also report poorer health than those with healthy children (Ha et al., 2008). Given these studies and the mix of information, one can conclude that parenthood does affect one’s physical and mental health, however, the extent of the effects are determined by a host of moderating variables.

9.4.3. Bereavement

Given the discussed benefits of marriage for both men and women, one would assume that the loss of a spouse would result in significant adverse health effects for both men and women. While this is generally the case, the effect of widowhood appears to have a more negative health effect on men’s health than women’s (Stroebe, Schut, & Stroebe, 2007). Following the death of a spouse, there is an increase in men’s mortality rate. In fact, the mortality rate for men is higher if widowed than married, however, the mortality rate for women is lower if widowed than married (Pizzetti & Manfredini, 2008).

One explanation for the gender differences with regards to effect of bereavement on overall health is daily stressors. After a spouse dies, women report experiencing more financial stress, whereas men report stress with household chores. This financial stress may be alleviated in time, however, household tasks need to be completed immediately.

Gender roles may also explain differences in response to the death of a spouse. For example, women are more likely to fulfill a caregiver role to the spouse, particularly if he is ill just prior to his death. Researchers argue that in the death of one’s husband, the role of caregiver is immediately removed, thus removing a daily stressor from a woman’s daily life, thus improving overall health.

Social support is another factor that is observed differently in men and women. More specifically, men rely more on their spouse for social support than women do. Women typically receive more of their social support from close friends; thus, the death of a spouse does not affect their support as much as it would for a man. This increase support outside of home for women is likely due to their willingness and desire to seek out support more than men. Men are also more likely to lose the established social support after widowhood as women are generally responsible for establishing and maintaining social engagements with friends and family. Carr and colleagues (2004) supported these theories by reporting that men were more interested in remarriage only when they lack social support from friends. Furthermore, social support mediated the relationship between gender and desire to remarry. More specifically, men were significantly more likely to want to remarry than women when receiving low levels of social support; however, there was not a difference in men and women’s desirability to remarry when both received high levels of social support.

9.4.3.1. Factors effecting bereavement research. These findings should be taken with caution as there are many issues with studies evaluating health of individuals following widowhood. One such issue is that healthier individuals are more likely to remarry after becoming widowed, and therefore, do not remain a widow for an extended period of time. These individuals may be excluded from specific studies, thus impacting the actual health findings of individuals post death of a spouse. Additionally, when individuals are recruited for a study, it is important that researchers control for the length of time since becoming a widow. As one can imagine, there could be varying degrees of coping that could impact an individual’s overall health.

Another important factor that researchers identify as an issue with bereavement studies is the inability to control for factors that may be contributing to one’s health issues that occurred prior to the death of their spouse. The only way to control for this issue is through prospective studies where individuals are assessed for years prior to the death of their spouse, and then reassessed at given time points post death. As you can imagine, this is not the best use of resources as the sample size would have to be very large. Additionally, you may be collecting data on individuals for many years as one cannot predict when someone’s life is likely to end. Some researchers argue that you could recruit individuals who engage in behaviors that are related to a higher likelihood of an early death, but that also presents confounds to the study as well.

Module Recap

As you can see, there are many factors that contribute to one’s health. We discussed the gender paradox that while women are more likely to be diagnosed with an illness, they are also less likely to die than men. This can be attributed to a host of things including better preventative care, as well as a longer life span. In addition to differences in mortality rates across genders, ethnicities, and countries, we also discussed the gender differences in two of the US leading causes of death: cardiovascular disease and cancer. We discussed the implications of both a positive health behavior (physical activity) as well as several negative health behaviors (obesity, alcohol, smoking, and drug use). These negative behaviors can have significant impact on both physical and mental well-being. Finally, we discussed the impact of environmental factors such as marriage, parenthood, and bereavement on one’s physical health. Furthermore, we discussed how the implications of these factors are different for men and women.