Gender Identity and Age

When do children start to learn about gender? Very early (Brown et al., 2020). Starting in infancy, children are learning about gender by observing the appearance, activities, and behavior of their caregivers and others around them (National Center on Parent, Family and Community Engagement, 2020). By their first birthday, children can distinguish faces by gender (Brown et al., 2020). As toddlers develop a sense of self, they use gender as one way to understand group belonging. Consequently, by their second birthday, they can label others’ gender and even sort objects into gender-typed categories. By the third birthday, children can consistently identify their own gender. At this age, children believe sex is determined by external attributes, such as appearance and specific behaviors, not biological attributes.

By five and six years of age, children hold the most rigid beliefs about what each gender can wear and behave, and they believe others may react negatively to any deviation from stereotypical gender norms (National Center on Parent, Family and Community Engagement, 2020). Stereotypes can refer to play (e.g., boys play with trucks, and girls play with dolls), traits (e.g., boys are strong, and girls like to cry), and occupations (e.g., men are doctors and women are nurses). Not surprisingly, children who exhibited the most gender stereotypical behavior at 3.5 years continued to demonstrate the most gender stereotypical behavior at 8 years of age. Similarly, those who exhibited the least gender typical behavior earlier also continued that way (Hines, 2015).

Adults may consciously, and unconsciously, encourage gender stereotypes (National Center on Parent, Family and Community Engagement, 2020). Girls are more likely to receive comments regarding their appearance, such as “What a pretty dress!” and “You are so cute!” In contrast, boys hear comments related to their abilities, such as “You are so smart!” or “You are so strong!” Further, the same behavior engenders different adult responses. When young children behave assertively, girls are criticized for being bossy, while boys are praised for being a leader. These stereotypes stay rigid until children reach about age 8 or 9. Then they develop cognitive abilities that allow them to be more flexible in their thinking about others (Brown et al., 2020).

Transgender Children: Many young children do not conform to the gender roles modeled by the culture and even push back against assigned roles. However, a small percentage of children actively reject the toys, clothing, and anatomy of their assigned sex and state they prefer the toys, clothing and anatomy of the opposite sex. Approximately 0.3 percent of the United States population identify as transgender (Olson & Gülgöz, 2018). Transgender adults have stated that they identified with the opposite gender as soon as they began talking (Russo, 2016). Some of these children may experience gender dysphoria, or distress accompanying a mismatch between one’s gender identity and biological sex (APA, 2013), while other children do not experience discomfort regarding their gender identity.

Current research is now looking at those young children who identify as transgender and have socially transitioned. In 2013, a longitudinal study following 300 socially transitioned transgender children between the ages of 3 and 12 began (Olson & Gülgöz, 2018). Socially transitioned transgender children identify with the gender opposite than the one assigned at birth, and they change their appearance and pronouns to reflect their gender identity. Findings from the study indicated that the gender development of these socially transitioned children looked similar to the gender development of cisgender children. These socially transitioned transgender children exhibited similar gender preferences and gender identities as their gender matched peers. Further, these children who were living everyday according to their gender identity and were supported by their families, exhibited positive mental health.

How Do We Learn about Gender?

Gender socialization focuses on what young children learn about gender from society, including parents, peers, media, religious institutions, schools, and public policies . Children learn about what is acceptable for females and males early , and i n fact, this socialization may even begin the moment a parent learns that a child is on the way. Knowing the sex of the child can conjure up images of the child’s behavior, appearance, and pote ntial on the part of a parent, a nd this stereotyping continues to guide perception through life. Consider parents of newborns, shown a 7 – pound, 20 – inch baby, wrapped in blue (a color designating males) describe the child as tough, strong, and angry when crying. Shown the same infant in pink (a color used in the United States for baby girls), these parents are likely to describe the baby as pretty, delic ate, and frustrated when crying (Maccoby & Jacklin, 1987). Femal e infants are held more, talked to more frequently and given direct eye contact, while male infant interactions are often mediated through a toy or activity. As they age, s ons are given tasks that take them outside the house and that have to be performed only on occasion , while girls are more likely to be given chores inside the home , such as cleaning or cooking that are performed daily. Sons are encouraged to think for themselves when they encounter problems and daughters are more likely to be given assi stance , even when they are working on an answer. Parents also talk to their children differently according to their gender. For example, parents talk to sons more in detail about science, and they discuss numbers and counting twice as often than with daugh ters (Chang et al., 2010). How are these beliefs about behaviors and expectations based on gender transmitted to children ?

Gender socialization focuses on what young children learn about gender from society, including parents, peers, media, religious institutions, schools, and public policies . Children learn about what is acceptable for females and males early , and i n fact, this socialization may even begin the moment a parent learns that a child is on the way. Knowing the sex of the child can conjure up images of the child’s behavior, appearance, and pote ntial on the part of a parent, a nd this stereotyping continues to guide perception through life. Consider parents of newborns, shown a 7 – pound, 20 – inch baby, wrapped in blue (a color designating males) describe the child as tough, strong, and angry when crying. Shown the same infant in pink (a color used in the United States for baby girls), these parents are likely to describe the baby as pretty, delic ate, and frustrated when crying (Maccoby & Jacklin, 1987). Femal e infants are held more, talked to more frequently and given direct eye contact, while male infant interactions are often mediated through a toy or activity. As they age, s ons are given tasks that take them outside the house and that have to be performed only on occasion , while girls are more likely to be given chores inside the home , such as cleaning or cooking that are performed daily. Sons are encouraged to think for themselves when they encounter problems and daughters are more likely to be given assi stance , even when they are working on an answer. Parents also talk to their children differently according to their gender. For example, parents talk to sons more in detail about science, and they discuss numbers and counting twice as often than with daugh ters (Chang et al., 2010). How are these beliefs about behaviors and expectations based on gender transmitted to children ?

Theories of Gender Development

Developmental Intergroup Theory:

Many of our gender stereotypes are so strong because we emphasize gender so much in culture (Bigler & Liben, 2007). For example, males and females are treated differently before they are even born. When someone learns of a new pregnancy, the first question asked is “Is it a boy or a girl?” Immediately upon hearing the answer, judgments are made about the child: Boys will be rough and like blue, while girls will be delicate and like pink. Developmental Intergroup Theory postulates that adults’ heavy focus on gender leads children to pay attention to gender as a key source of information about themselves and others, to seek out any possible gender differences, and to form rigid stereotypes based on gender that are subsequently difficult to change.

![Photo: Billy V, https://goo.gl/Kb2MuL, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, https://goo.gl/Toc0ZF] Three female fire fighters are leaning against the front of a fire truck](https://socialsci.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/127112/original.jpg?revision=1)

Gender Schema theory:

There are also psychological theories that partially explain how children form their own gender roles after they learn to differentiate based on gender. The first of these theories argues that children are active learners who essentially socialize themselves. In this case, children actively organize others’ behavior, activities, and attributes into gender categories, which are known asgender schemas (Bem, 1981). As children learn various gender related information they build their gender schemas, which enables them to seek out and notice other gender related information. These gender schemas come to guide understanding and memory of gender relevant information (Bem, 1981). People of all ages are more likely to remember schema-consistent behaviors and attributes than schema-inconsistent behaviors and attributes. So, people are more likely to remember men, and forget women, who are firefighters. They also misremember schema-inconsistent information. If research participants are shown pictures of someone standing at the stove, they are more likely to remember the person to be cooking if depicted as a woman, and the person repairing the stove if depicted as a man. By only remembering schema-consistent information, gender schemas strengthen more and more over time. Children may also begin to incorporate this information into their self-concept. However, people differ in the degree to which they use gender schemas to interpret both themselves and the world (Bem, 1983). Bem proposed that some people are more gender schematic, that is they are especially attuned to gender, and use it as a way of organizing and understanding the world. In contrast, those who are gender aschematicdo not use gender as a dimension for interpreting the world.

Social Learning Theory:

Another theory that attempts to explain the formation of gender roles in children is Social Learning Theory, which argues that behavior is learned through observation, modeling, reinforcement, and punishment (Bandura, 1997). Sex typing (Mischel, 1966) is the process by which individuals acquire patterns of gendered behavior. Children are rewarded and reinforced for behaving in concordance with gender roles and punished for breaking gender roles. In addition, social learning theory argues that children learn many of their gender roles by modeling the behavior of adults and older children and, in doing so, develop ideas about what behaviors are appropriate for each gender. Children can also observe the behavior of models, but not perform these behaviors for sometime. Parents are an important source of the punishments and rewards for children’s gendered behavior. Parents influence the toys, décor of bedrooms, clothing, and activities that children are allowed to engage in.

Cognitive Social Learning Theoryalso emphasizes reinforcement, punishment, and imitation, but adds cognitive processes. These processes include attention, self-regulation, and self-efficacy. Once children learn the significance of gender, they regulate their own behavior based on internalized gender norms (Bussey & Bandura, 1999). Social learning theory has less support than gender schema theory; research shows that parents do reinforce gender-appropriate play, but for the most part treat their male and female children similarly (Lytton & Romney, 1991).

Objectification Theoryfocuses on how the female body has become an object of the male gaze (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018). When objectified, female attractiveness is valued above all other factors. Living in a culture that objectifies women, young girls internalize the beauty standards they see in the media and around them. Consequently, they attempt to attain these standards and regularly monitor and change their bodies as a way to conform. Because these standards are unrealistic, girls and women feel shame, anxiety, or depression for not achieving the cultural ideal. Additionally, internalizing one’s body as an object impairs cognitive performance.

Ecological Systems Theory:

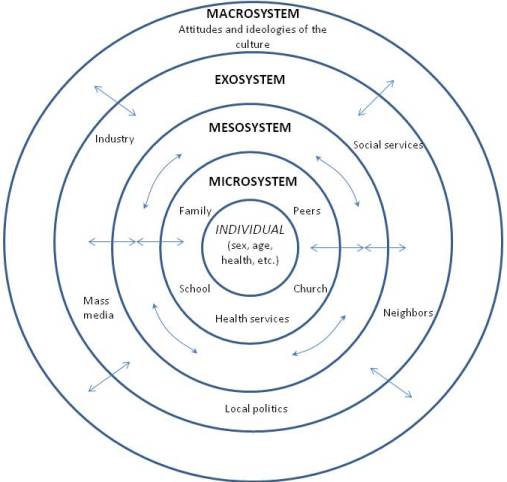

Bronfenbrenner developed the Ecological Systems Theory, which provides a framework for understanding and studying the many influences on human development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Bronfenbrenner recognized that human interaction is influenced by larger social forces and that an understanding of these forces is essential for understanding an individual. The individual is impacted by several systems including:

- Microsystemincludes the individual’s setting and those who have direct, significant contact with the person, such as parents or siblings. The input of those is modified by the cognitive and biological state of the individual as well. These influence people’s actions, which in turn influence systems operating on them.

- Mesosytemincludes the larger organizational structures, such as school, the family, or religion. These institutions impact the microsystems just described. The philosophy of the school system, daily routine, assessment methods, and other characteristics can affect the child’s self-image, growth, sense of accomplishment, and schedule thereby impacting the child, physically, cognitively, and emotionally.

- Exosystem includes the larger contexts of community. A community’s values, history, and economy can impact the organizational structures it houses. Mesosystems both influence and are influenced by the exosystem.

- Macrosystem includes the cultural elements, such as global economic conditions, war, technological trends, values, philosophies, and a society’s responses to the global community.

- Chronosystem is the historical context in which these experiences occur. This relates to the different generational time periods, such as the baby boomers and millennials.

In sum, a child’s experiences are shaped by larger forces such as the family, schools, religion, culture, and time period. Bronfenbrenner’s model helps us understand all of the different environments that impact each one of us simultaneously. Despite its comprehensiveness, Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system’s theory is not easy to use. Taking into consideration all the different influences makes it difficult to research and determine the impact of all the different variables (Dixon, 2003). Consequently, psychologists have not fully adopted this approach, although they recognize the importance of the ecology of the individual. Below is a model of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory.

Sources of Socialization

Parents:

Brody’s Transactional Model explains how children learn gender roles by focusing on the bidirectional influences between parents and children (Brody, 1999). Brody’s transactional model indicates that the infant’s gender and temperament begin the socialization process as parents reinforce temperamental qualities. For example, girls tend to be more sociable, talkative, and develop self-control earlier. Consequently, parents encourage their social skill development and emotional control, which align with female gender roles. Boys are more physically active, which is also encouraged through parenting.

Parents often have different expectations and perceptions based on the child’s gender. Boys are encouraged to be more independent, while girls are reinforced for staying close and being more dependent (Hines, 2015). A recent study (MacPhee & Prendergast, 2019) found that children’s bedrooms were still as gendered today as they were over 40 years ago. Additionally, girls receive more positive reinforcement when they play with girls’ toys, and boys receive such reinforcement when they play with boys’ toys (Hines, 2015). Girls tend to receive toys that highlight nurturing behavior and physical attractiveness, such as baby dolls and dress-up, while for boys the toys focus on competitiveness and action, such as sports equipment and racing cars. Boe and Woods (2018) found that even by 12 ½ months of age infants were already showing clear gender-stereotypical toy preferences. According to Hines (2015), parents encourage the most gender stereotypical toy choices when the child is two years of age. Preschool children can predict how parents might respond if they were to play with cross-gender toys (Freeman, 2007). Fathers, in particular, react more strongly to their son playing with a doll, than their daughter playing with a truck (Basow, 2008). Thus, boys are more gender socialized than are girls, and may explain the greater sex-typed behavior, attitudes, and preferences of boys (Bosson et al., 2019).

Parents own gendered behavior also influences their children’s gender development. Parents who split house-hold chores along traditional gender roles have children with more gender typical behavior (Hines et al., 2002). The same longitudinal study also found that children of mothers who work outside of the home, or who are more educated display less gender stereotypical behavior. Children raise by same-sex parents also display less gender stereotypical behavior and attitudes (Sutfin et al., 2008) as they presumably see both parents engaging in traditionally male and female tasks.

Siblings:

Siblings can serve as role models, companions, and sources of advice, especially in areas that parents may seem as being less knowledgeable, such as peers and social trends (Marks et al., 2009). In their research Marks and colleagues assessed the gender role attitudes of siblings in families with children who were no more than four years apart in age, and the youngest was at least school age. Female siblings (whether first or second born) were more egalitarian in their gender role views than were male siblings. However, they found that regardless of gender, sibling dyads were consistent in their gender role attitudes. In fact, no sibling dyad was incongruent, yet at least a quarter of sibling pairs were inconsistent with their parents’ views. This is consistent with an earlier study (McHale et al., 2001) who reported more evidence for sibling than parental influence on gender role attitudes.

Siblings can serve as role models, companions, and sources of advice, especially in areas that parents may seem as being less knowledgeable, such as peers and social trends (Marks et al., 2009). In their research Marks and colleagues assessed the gender role attitudes of siblings in families with children who were no more than four years apart in age, and the youngest was at least school age. Female siblings (whether first or second born) were more egalitarian in their gender role views than were male siblings. However, they found that regardless of gender, sibling dyads were consistent in their gender role attitudes. In fact, no sibling dyad was incongruent, yet at least a quarter of sibling pairs were inconsistent with their parents’ views. This is consistent with an earlier study (McHale et al., 2001) who reported more evidence for sibling than parental influence on gender role attitudes.

Peers:

Brody’s Transactional Model (1999), focusing on bidirectional interactions, also holds true for peers. Children tend to play with others of the same gender, and through their play, children observe, practice, and encourage each other to engage in gender-typical behavior (Hines, 2015). At 4.5 years of age, children play with same gender peers three times more than other-gender peers, and by 6.5 years, they play ten times more with same gender peers. As children become older, peers reinforce gender stereotypes, especially emotional displays. Girls will reinforce warm interactions and the display of emotional expressions, including sadness. Conversely, boys will reinforce competition among each other and discourage displays of sadness. In fact, boys who do express sadness are less accepted, less popular, and more likely to be teased. Consequently, children and adolescents will adhere to these gender roles so they are not ostracized from their peers.

Brody’s Transactional Model (1999), focusing on bidirectional interactions, also holds true for peers. Children tend to play with others of the same gender, and through their play, children observe, practice, and encourage each other to engage in gender-typical behavior (Hines, 2015). At 4.5 years of age, children play with same gender peers three times more than other-gender peers, and by 6.5 years, they play ten times more with same gender peers. As children become older, peers reinforce gender stereotypes, especially emotional displays. Girls will reinforce warm interactions and the display of emotional expressions, including sadness. Conversely, boys will reinforce competition among each other and discourage displays of sadness. In fact, boys who do express sadness are less accepted, less popular, and more likely to be teased. Consequently, children and adolescents will adhere to these gender roles so they are not ostracized from their peers.

Lee and Troop-Gordon (2011) studied how children reacted to peers who chastised them for gender atypical behavior. They found that boys with many male peers were more likely to punish behavior that was seen as being feminine, and as a result these boys were less likely to exhibit gender atypical behavior in front of other boys. In contrast, boys with few male friends, even when punished for gender atypical behavior, did not reduce this behavior. Having fewer male peers meant these boys experienced less pressure to conform to the stereotypes and thus, were less likely to display gender stereotypical behavior. For girls, female peers were less likely to criticize female or male friends who acted atypical for their gender. However, girls with many male friends were more likely to be criticized for not acting like a girl, and thus were more likely to exhibit a behavioral change. It appears that male friendships demand more gender role conformity, while female friendships may allow for greater flexibility.

Teachers:

Gender stereotypes regarding academic performance assume that boys demonstrate higher mathematics ability, while girls exhibit higher language-related skills. Not surprisingly, the academic strengths students possesses correlate with their self-concept in these areas. Specifically, boys demonstrate higher mathematics self-concepts and girls exhibit higher language-related self-concepts (Watt & Eccles, 2008). Is it just ability, or are there other factors that contribute to students’ self-concept in specific academic areas? In a longitudinal study, Retelsdorf et al. (2015) found a negative correlation between teacher’s gender stereotypes regarding boys’ reading ability at the beginning of fifth grade, and boys’ reading self-concept at the end of sixth grade. The authors concluded that gender differences in self-concept held by students are correlated to the stereotypical beliefs held by teachers. Consequently, they encourage teachers to counteract prior gender stereotypes and become aware of their own potentially discriminatory behaviors.

In another longitudinal study, Garcia et al. (2019) reported that teachers viewed boys as having worse executive functions than girls have. Executive functionsare higher order cognitive skills, including planning, cognitive flexibility, working memory, inhibitory behavior, goal-setting and problem solving, that contribute to classroom success. The authors contend that the teachers’ perceptions of male students possessing lower executive functions contributed to the persistent gender disparities in academic and behavioral outcomes. Again, gender role stereotypes appear to adversely affect school achievement for boys. It must also be noted that African American students, and those with limited English proficiency, were also rated as having lower executive functions demonstrating the intersectionality of the results.

Focusing on mathematics achievement, results from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998–1999, indicate the average mathematics achievement of boys and girls is similar in kindergarten, but by the spring of third grade, a male advantage of approximately one quarter of a standard deviation has developed (Robinson-Cimpian et al., 2014). What accounts for this difference? According to Robinson-Cimpian and colleagues, elementary school teachers’ perceptions are the reason. Teachers rate boys as more proficient in mathematics, and they view girls as mathematically competent, only when the girls are also seen as hard working, well behaved, and more eager to learn. The authors concluded that the underrating of girls’ mathematical proficiency accounts for the resulting gender achievement gap in the early grades.

Focusing on mathematics achievement, results from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998–1999, indicate the average mathematics achievement of boys and girls is similar in kindergarten, but by the spring of third grade, a male advantage of approximately one quarter of a standard deviation has developed (Robinson-Cimpian et al., 2014). What accounts for this difference? According to Robinson-Cimpian and colleagues, elementary school teachers’ perceptions are the reason. Teachers rate boys as more proficient in mathematics, and they view girls as mathematically competent, only when the girls are also seen as hard working, well behaved, and more eager to learn. The authors concluded that the underrating of girls’ mathematical proficiency accounts for the resulting gender achievement gap in the early grades.

An additional factor contributing to academic performance differences between boys and girls include teacher-student relationships. According to McCormick and O’Connor (2015), an overall higher quality relationship, characterized by low levels of conflict and high levels of closeness, occurs between girls and their teachers. This stronger relationship contributes to teachers rating girls higher on assessments of academic competence. One reason given for this difference is the increased level of disruption demonstrated by boys, and the resulting belief that girls are the easier students to teach. Not surprisingly, when girls have a poor relationship with a teacher, they may internalize negative feelings toward school, which can adversely affect their academic performance. Consequently, stereotypes regarding who is a “model student” in the classroom affects the achievement for both boys and girls. As can be seen in the above research, teachers hold gender stereotypes that negatively affect student academic achievement.

Media:

Another significant way gender role socialization occurs is through media. Television, movies, advertisements, music, magazines, books, video games, and social media all contribute to gender stereotypes, and this exposure begins very early in a child’s life. Kirsch and Murnen (2015) reviewed the research on how female and male characters are represented across a variety of children’s programming and found that females are more likely to be depicted as frail, attractive, emotional, and worried about their appearance. Additionally, female characters demonstrate deference, dependence and nurturance. They also show fear, politeness, and act romantic and supportive. In contrast, male characters were more likely to exhibit dominance, aggression, and attention-seeking behaviors. Both cultivation theory, which states that repeated exposure to media encourages beliefs depicted in that reality, and objectification theory explain the effects of sexist media on gender stereotypes (Stermer & Burkley, 2015). Frequent exposure to sexist media that focus on male dominance and female sexual and submissive attributes, correlates with the objectification of women and reinforcement of rigid stereotypes.

Another significant way gender role socialization occurs is through media. Television, movies, advertisements, music, magazines, books, video games, and social media all contribute to gender stereotypes, and this exposure begins very early in a child’s life. Kirsch and Murnen (2015) reviewed the research on how female and male characters are represented across a variety of children’s programming and found that females are more likely to be depicted as frail, attractive, emotional, and worried about their appearance. Additionally, female characters demonstrate deference, dependence and nurturance. They also show fear, politeness, and act romantic and supportive. In contrast, male characters were more likely to exhibit dominance, aggression, and attention-seeking behaviors. Both cultivation theory, which states that repeated exposure to media encourages beliefs depicted in that reality, and objectification theory explain the effects of sexist media on gender stereotypes (Stermer & Burkley, 2015). Frequent exposure to sexist media that focus on male dominance and female sexual and submissive attributes, correlates with the objectification of women and reinforcement of rigid stereotypes.

Common Sense, a nonprofit organization focused on how children are affected by media and technology, analyzed the research on how the gender stereotypes shown in movies and television actually affect children’s development. The report from Common Sense (2017) made the following conclusions:

“Findings indicate that heavier TV viewing, especially of content that features traditional gender representations, can lead children and adolescents to hold more rigid or stereotypical beliefs about what each gender can and should do; leads to more stereotypical toy, activity, and occupation preferences; and limits children’s perceptions of their own abilities and future options. For girls, this often means that they steer their focus onto their appearance, bodies, and sexiness and away from their competencies, especially in academics, science, and math. For boys, this means drawing a narrow construction of what both femininity and masculinity are and steering away from “softer” values such as nurturance, compassion, and romantic love,” (p. 38).

Because gender stereotypes in advertising perpetuate gender-role stereotypes in a culture, do countries with greater gender equality experience less sexist commercials? Matthes et al. (2016) studied the depiction of men and women in 1755 television advertisements in 13 countries by analyzing the gender of the primary character and voiceover, characters’ ages, product categories, home- or work setting, and the working role of the primary character. The authors found that gender stereotypes in TV advertising can be found around the world, independent of a given gender equality status in a particular country. Contrary to what was expected, more progressive countries did not depict women in more progressive ways in television advertising. Clearly, gender role stereotypes in media are a significant socializing factor for children acquiring and internalizing these stereotypes.

Video Games:

When reviewing different types of popular media, some of the most blatant examples of sexism is considered to occur in video games (Stermer & Burkley, 2015). From the birth of video games, Stermer and Burkley state they have portrayed females in sexist ways, including as damsels in distress, rewards for male characters, and an object of men’s fantasies. In their review of the research, the authors include studies showing that males who frequently play sexualized video games were higher in rape inclination and rape myth acceptance. Additionally, study participants also viewed a rape victim more negatively, exhibited greater tolerance of sexual harassment, exhibited higher levels of benevolent sexism, thought of women as sex objects, and attributed less cognitive capability to the character when playing as a sexualized female character compared to a nonsexualized female character.

To explain these results, Stermer and Burkley also endorse cultivation theory. For video games, this means that players repeatedly shown sexist imagery and characterizations will embrace these images and internalize the sexist beliefs. Social learning theory, which explains how observing others affects one’s attitudes and behavior, is also provided as a reason why playing sexualized video games correlates with sexist attitudes. Lastly, objectification theory, which views women as sexualized objects for the male gaze, explains how sexist video games reinforce female stereotypes as sexual and submissive beings.

Media and the Thin Ideal:

For women in Western cultures, a common attitude is that thinness is beauty. Advertisers focus on this belief and create ads based on the “thin ideal” as a way to market what is deemed attractive and desirable to others (Mills et al., 2017). Thin ideal images often accompany various advertised products, the pairing of which reinforces the idea that if you buy or use a particular product, you, too, can be beautiful. Television and movies also encourage the thin ideal as both female models and actresses possess a lower Body Mass Index (BMI) than what is actually measured for women and what is considered ideal for women (CDC, 2020).

| Female Category |

BMI Range |

| Average Weight of Models |

BMI=15-16 |

| Average Weight of Actresses |

BMI=17-20 |

| CDC Healthy Female Weight |

BMI=18.5-24.9 |

| Average Female Weight |

BMI=29.6 |

How does idealized body images affect one’s self-perception? According to Mills et al. (2017), there is robust empirical support for the idea that exposure to idealized body images in traditional forms of media (e.g. magazines and television) affects perceptions of beauty and appearance concerns by leading women to internalize a very slender female body type as ideal or beautiful. There is also support for the idea that exposure to the thin ideal is associated with body dissatisfaction in the moment among women. While most of the research on this topic has been conducted with female participants, there is also some research on male participants. Men’s and women’s body ideals vary considerably in Western cultures, where most of this research has been conducted. While women’s body ideal is slim, men’s is lean, but well‐defined and muscular. In sum, the association between exposure to idealized body images in the media and body dissatisfaction holds true for both men and women, with the effect in women being slightly stronger than in men.

Social Media:

In line with research on traditional forms of mass media and body image, recent correlational studies reveal that social media use, including Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat and Pinterest, is linked to body image and appearance concerns among both men and women. One of the unique aspects of social media, versus traditional media, is that they are made up of communication with peers and/or public figures. It is the elements of interactivity and connectedness that make social media distinct from other media forms and rife with opportunities for users to perceive, compare, and internalize standards of beauty. Traditional media literacy efforts may have helped people think critically about how photos of models and celebrities are frequently edited by advertisers and editors, and how they display completely unrealistic standards of beauty. However, social media platforms expose users to photos of real‐world peers, which may dissuade people from critically analyzing the images they see on social media. In truth, users can present their ideal selves through editing, enhancing, and embellishing their online images and appearance. Whether social media users engage in selective presentation of their own appearance, but overlook the notion that other users have done the same, still needs to be researched (Mills et al., 2017).

In line with research on traditional forms of mass media and body image, recent correlational studies reveal that social media use, including Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat and Pinterest, is linked to body image and appearance concerns among both men and women. One of the unique aspects of social media, versus traditional media, is that they are made up of communication with peers and/or public figures. It is the elements of interactivity and connectedness that make social media distinct from other media forms and rife with opportunities for users to perceive, compare, and internalize standards of beauty. Traditional media literacy efforts may have helped people think critically about how photos of models and celebrities are frequently edited by advertisers and editors, and how they display completely unrealistic standards of beauty. However, social media platforms expose users to photos of real‐world peers, which may dissuade people from critically analyzing the images they see on social media. In truth, users can present their ideal selves through editing, enhancing, and embellishing their online images and appearance. Whether social media users engage in selective presentation of their own appearance, but overlook the notion that other users have done the same, still needs to be researched (Mills et al., 2017).

Religion:

According to Haggard et al. (2019), “many world religions endorse sex segregated worship practices, gendered standards of sanctification, and strict patriarchal family life” (p. 392). Judaism, Christianity, Mormonism, and Islam account for more than half of the world’s religious believers, and all four religions support an organizational structure that endorses separate expectations for men and women in both the home and sacred spaces. Overall, religiosity is correlated with negative attitudes toward women and less access to education, employment, and maternal care for women, regardless of a country’s economic development. Additionally, there is an increase in positive feelings toward women, or benevolent sexism, who follow gendered stereotypes and rules. Religious beliefs and culture are often difficult to separate, and many religious practices that oppress women are often reflective of the culture rather than the religion. This is especially true for Muslim women who, in many countries, are subjected to strict behavioral control based on the culture and not the Quran, Islam’s holy book (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018).

According to Haggard et al. (2019), “many world religions endorse sex segregated worship practices, gendered standards of sanctification, and strict patriarchal family life” (p. 392). Judaism, Christianity, Mormonism, and Islam account for more than half of the world’s religious believers, and all four religions support an organizational structure that endorses separate expectations for men and women in both the home and sacred spaces. Overall, religiosity is correlated with negative attitudes toward women and less access to education, employment, and maternal care for women, regardless of a country’s economic development. Additionally, there is an increase in positive feelings toward women, or benevolent sexism, who follow gendered stereotypes and rules. Religious beliefs and culture are often difficult to separate, and many religious practices that oppress women are often reflective of the culture rather than the religion. This is especially true for Muslim women who, in many countries, are subjected to strict behavioral control based on the culture and not the Quran, Islam’s holy book (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018).

Gendered Language Development

Language contributes to children’s beliefs about gender by treating gender as a binary, thus leading to gender stereotypes and biases. In a review of how languages vary in their marking of gender, Bigler and Leaper (2015) identify three types of languages:

- Gendered languages mark nouns and pronouns for gender

- Natural Gender languages mark gender with third-person singular pronouns (e.g., he, she, his, her)

- Genderless languages do not mark either nouns or pronouns for gender

The English language is categorized as a natural gender language, while Spanish would be considered a gendered language. In English, many nouns reflect the gender binary, including names of family members (daughter, wife, sister) and careers (fireman, congressman). For those who do not identify with the gender binary, or who prefer not to be identified by their gender, these words would not be appropriate. Switching to the use of gender-neutral nouns is possible in most situations, and there is growing support to refrain from marking gender unnecessarily. Replacements for gendered language are listed below:

| Gender-Neutral Language |

Gendered Language |

| Children |

Daughter and Son |

| Spouse or Partner |

Wife, Husband, Girlfriend, Boyfriend |

| Fire Fighter or Police Officer |

Fireman, Police woman |

| Students |

Girls and Boys |

| People |

Men and Women |

| Chair |

Chairman and Chairwoman |

| Mx. |

Ms. And Mr. |

Observational research has also indicated that gendered nouns can appear with descriptors that indicate broad generalizations about those on the gender binary (Bigler & Leaper, 2015). Children hear such statements as, “Girls wear pink” or “Boys like trucks”, and they do not readily hear statements that reflect within-gender variability, such as “Some girls like to wear pink” or overlap between the binary genders, “Both girls and boys like to play with trucks”. These descriptive gender-generic noun phrases can promote gender stereotypes in children. Other examples of gendered language children hear include honorific titles, such as Miss, Mrs., Ms., and Mr., which mark the gender of the individual. For females, these titles can also indicate marital status not reflected in the male title.

Pronoun use in English, which focuses on only one individual, has traditionally reflected the gender binary using the following terms: he, she, his, or her. Consequently, using these pronouns makes assumptions about the gender of the individual that may be wrong. Therefore, using the pronouns ‘they” and “their” to reflect single individuals is now advocated. The American Psychological Association (APA) endorses the use of generic third-person pronouns in the latest edition of their publication manual. According to the APA (2020), “The use of the singular ‘they’ is inclusive of all people, helps writers avoid making assumptions about gender, and is part of APA Style” (p. 121).

Another concern with the use of masculine generic nouns and the pronouns “he” or “him”, is that they have historically been used as a replacement for all individuals, not just males. When this occurs, children imagine the individual (including animals) as a male rather than as a representative of all people. Additionally, the frequent use of masculine generic nouns promotes a higher status of males compared to females (Bigler & Leaper, 2015)

Research has also looked at gender differences between affiliative and self-assertive speech patterns in children. According to Leaper and Smith (2004), affiliative speechrefers to language used to establish or maintain connections with others, while self-assertive speechrefers to language used to influence others. In a review of three sets of meta-analyses, Leaper and Smith came to the following conclusions. First, girls were only slightly more talkative than boys were, and they used more affiliative speech. Second, there was a significant, but small, indication that boys used self-assertive speech more than girls did. These results were interpreted according to traditional gender socialization that emphasizes girls playing in more communal and nurturing ways, while dominance and instrumentality are encouraged in the play of boys. However, group size was important to the type of speech used. Specifically, boys used speech that was more assertive in dyads than when they were in groups of three or more children or in mixed gender groups. The authors hypothesized that both boys and girls may demonstrate self-assertive speech in larger groups to maintain their position within the group.

![Photo: Billy V, https://goo.gl/Kb2MuL, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, https://goo.gl/Toc0ZF] Three female fire fighters are leaning against the front of a fire truck](https://socialsci.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/127112/original.jpg?revision=1)

Siblings can serve as role models, companions, and sources of advice, especially in areas that parents may seem as being less knowledgeable, such as peers and social trends (Marks et al., 2009). In their research Marks and colleagues assessed the gender role attitudes of siblings in families with children who were no more than four years apart in age, and the youngest was at least school age. Female siblings (whether first or second born) were more egalitarian in their gender role views than were male siblings. However, they found that regardless of gender, sibling dyads were consistent in their gender role attitudes. In fact, no sibling dyad was incongruent, yet at least a quarter of sibling pairs were inconsistent with their parents’ views. This is consistent with an earlier study (McHale et al., 2001) who reported more evidence for sibling than parental influence on gender role attitudes.

Siblings can serve as role models, companions, and sources of advice, especially in areas that parents may seem as being less knowledgeable, such as peers and social trends (Marks et al., 2009). In their research Marks and colleagues assessed the gender role attitudes of siblings in families with children who were no more than four years apart in age, and the youngest was at least school age. Female siblings (whether first or second born) were more egalitarian in their gender role views than were male siblings. However, they found that regardless of gender, sibling dyads were consistent in their gender role attitudes. In fact, no sibling dyad was incongruent, yet at least a quarter of sibling pairs were inconsistent with their parents’ views. This is consistent with an earlier study (McHale et al., 2001) who reported more evidence for sibling than parental influence on gender role attitudes. Brody’s Transactional Model (1999), focusing on bidirectional interactions, also holds true for peers. Children tend to play with others of the same gender, and through their play, children observe, practice, and encourage each other to engage in gender-typical behavior (Hines, 2015). At 4.5 years of age, children play with same gender peers three times more than other-gender peers, and by 6.5 years, they play ten times more with same gender peers. As children become older, peers reinforce gender stereotypes, especially emotional displays. Girls will reinforce warm interactions and the display of emotional expressions, including sadness. Conversely, boys will reinforce competition among each other and discourage displays of sadness. In fact, boys who do express sadness are less accepted, less popular, and more likely to be teased. Consequently, children and adolescents will adhere to these gender roles so they are not ostracized from their peers.

Brody’s Transactional Model (1999), focusing on bidirectional interactions, also holds true for peers. Children tend to play with others of the same gender, and through their play, children observe, practice, and encourage each other to engage in gender-typical behavior (Hines, 2015). At 4.5 years of age, children play with same gender peers three times more than other-gender peers, and by 6.5 years, they play ten times more with same gender peers. As children become older, peers reinforce gender stereotypes, especially emotional displays. Girls will reinforce warm interactions and the display of emotional expressions, including sadness. Conversely, boys will reinforce competition among each other and discourage displays of sadness. In fact, boys who do express sadness are less accepted, less popular, and more likely to be teased. Consequently, children and adolescents will adhere to these gender roles so they are not ostracized from their peers. Focusing on mathematics achievement, results from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998–1999, indicate the average mathematics achievement of boys and girls is similar in kindergarten, but by the spring of third grade, a male advantage of approximately one quarter of a standard deviation has developed (Robinson-Cimpian et al., 2014). What accounts for this difference? According to Robinson-Cimpian and colleagues, elementary school teachers’ perceptions are the reason. Teachers rate boys as more proficient in mathematics, and they view girls as mathematically competent, only when the girls are also seen as hard working, well behaved, and more eager to learn. The authors concluded that the underrating of girls’ mathematical proficiency accounts for the resulting gender achievement gap in the early grades.

Focusing on mathematics achievement, results from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998–1999, indicate the average mathematics achievement of boys and girls is similar in kindergarten, but by the spring of third grade, a male advantage of approximately one quarter of a standard deviation has developed (Robinson-Cimpian et al., 2014). What accounts for this difference? According to Robinson-Cimpian and colleagues, elementary school teachers’ perceptions are the reason. Teachers rate boys as more proficient in mathematics, and they view girls as mathematically competent, only when the girls are also seen as hard working, well behaved, and more eager to learn. The authors concluded that the underrating of girls’ mathematical proficiency accounts for the resulting gender achievement gap in the early grades. Another significant way gender role socialization occurs is through media. Television, movies, advertisements, music, magazines, books, video games, and social media all contribute to gender stereotypes, and this exposure begins very early in a child’s life. Kirsch and Murnen (2015) reviewed the research on how female and male characters are represented across a variety of children’s programming and found that females are more likely to be depicted as frail, attractive, emotional, and worried about their appearance. Additionally, female characters demonstrate deference, dependence and nurturance. They also show fear, politeness, and act romantic and supportive. In contrast, male characters were more likely to exhibit dominance, aggression, and attention-seeking behaviors. Both cultivation theory, which states that repeated exposure to media encourages beliefs depicted in that reality, and objectification theory explain the effects of sexist media on gender stereotypes (Stermer & Burkley, 2015). Frequent exposure to sexist media that focus on male dominance and female sexual and submissive attributes, correlates with the objectification of women and reinforcement of rigid stereotypes.

Another significant way gender role socialization occurs is through media. Television, movies, advertisements, music, magazines, books, video games, and social media all contribute to gender stereotypes, and this exposure begins very early in a child’s life. Kirsch and Murnen (2015) reviewed the research on how female and male characters are represented across a variety of children’s programming and found that females are more likely to be depicted as frail, attractive, emotional, and worried about their appearance. Additionally, female characters demonstrate deference, dependence and nurturance. They also show fear, politeness, and act romantic and supportive. In contrast, male characters were more likely to exhibit dominance, aggression, and attention-seeking behaviors. Both cultivation theory, which states that repeated exposure to media encourages beliefs depicted in that reality, and objectification theory explain the effects of sexist media on gender stereotypes (Stermer & Burkley, 2015). Frequent exposure to sexist media that focus on male dominance and female sexual and submissive attributes, correlates with the objectification of women and reinforcement of rigid stereotypes. In line with research on traditional forms of mass media and body image, recent correlational studies reveal that social media use, including Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat and Pinterest, is linked to body image and appearance concerns among both men and women. One of the unique aspects of social media, versus traditional media, is that they are made up of communication with peers and/or public figures. It is the elements of interactivity and connectedness that make social media distinct from other media forms and rife with opportunities for users to perceive, compare, and internalize standards of beauty. Traditional media literacy efforts may have helped people think critically about how photos of models and celebrities are frequently edited by advertisers and editors, and how they display completely unrealistic standards of beauty. However, social media platforms expose users to photos of real‐world peers, which may dissuade people from critically analyzing the images they see on social media. In truth, users can present their ideal selves through editing, enhancing, and embellishing their online images and appearance. Whether social media users engage in selective presentation of their own appearance, but overlook the notion that other users have done the same, still needs to be researched (Mills et al., 2017).

In line with research on traditional forms of mass media and body image, recent correlational studies reveal that social media use, including Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat and Pinterest, is linked to body image and appearance concerns among both men and women. One of the unique aspects of social media, versus traditional media, is that they are made up of communication with peers and/or public figures. It is the elements of interactivity and connectedness that make social media distinct from other media forms and rife with opportunities for users to perceive, compare, and internalize standards of beauty. Traditional media literacy efforts may have helped people think critically about how photos of models and celebrities are frequently edited by advertisers and editors, and how they display completely unrealistic standards of beauty. However, social media platforms expose users to photos of real‐world peers, which may dissuade people from critically analyzing the images they see on social media. In truth, users can present their ideal selves through editing, enhancing, and embellishing their online images and appearance. Whether social media users engage in selective presentation of their own appearance, but overlook the notion that other users have done the same, still needs to be researched (Mills et al., 2017). According to Haggard et al. (2019), “many world religions endorse sex segregated worship practices, gendered standards of sanctification, and strict patriarchal family life” (p. 392). Judaism, Christianity, Mormonism, and Islam account for more than half of the world’s religious believers, and all four religions support an organizational structure that endorses separate expectations for men and women in both the home and sacred spaces. Overall, religiosity is correlated with negative attitudes toward women and less access to education, employment, and maternal care for women, regardless of a country’s economic development. Additionally, there is an increase in positive feelings toward women, or benevolent sexism, who follow gendered stereotypes and rules. Religious beliefs and culture are often difficult to separate, and many religious practices that oppress women are often reflective of the culture rather than the religion. This is especially true for Muslim women who, in many countries, are subjected to strict behavioral control based on the culture and not the Quran, Islam’s holy book (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018).

According to Haggard et al. (2019), “many world religions endorse sex segregated worship practices, gendered standards of sanctification, and strict patriarchal family life” (p. 392). Judaism, Christianity, Mormonism, and Islam account for more than half of the world’s religious believers, and all four religions support an organizational structure that endorses separate expectations for men and women in both the home and sacred spaces. Overall, religiosity is correlated with negative attitudes toward women and less access to education, employment, and maternal care for women, regardless of a country’s economic development. Additionally, there is an increase in positive feelings toward women, or benevolent sexism, who follow gendered stereotypes and rules. Religious beliefs and culture are often difficult to separate, and many religious practices that oppress women are often reflective of the culture rather than the religion. This is especially true for Muslim women who, in many countries, are subjected to strict behavioral control based on the culture and not the Quran, Islam’s holy book (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018). There are two theories with regard to lifespan gender development: cross over and degendering. Cross over theory (Gutmann, 1975) suggests that the changes in our social roles as we move through middle and late adulthood would likely lead to greater similarity between the genders in terms of how they see themselves. Degendering theory (Silver, 2003) proposes that as people age, gender and the social expectations of gender becomes less central to people’s self-concept. The personality research does suggest a degree of gender convergence with men and women becoming more similar with age, in line with the predictions of cross over theory. Lemaster el al. (2015) found little support for degendering. In their research men and women often saw themselves as more typical of their gender group the older they were, suggesting that gender was still very central to their self-concept even in their 60s. They also found that this tendency was stronger for men than for women as they aged, suggesting that the need to validate manhood is still present even in middle aged and older males.

There are two theories with regard to lifespan gender development: cross over and degendering. Cross over theory (Gutmann, 1975) suggests that the changes in our social roles as we move through middle and late adulthood would likely lead to greater similarity between the genders in terms of how they see themselves. Degendering theory (Silver, 2003) proposes that as people age, gender and the social expectations of gender becomes less central to people’s self-concept. The personality research does suggest a degree of gender convergence with men and women becoming more similar with age, in line with the predictions of cross over theory. Lemaster el al. (2015) found little support for degendering. In their research men and women often saw themselves as more typical of their gender group the older they were, suggesting that gender was still very central to their self-concept even in their 60s. They also found that this tendency was stronger for men than for women as they aged, suggesting that the need to validate manhood is still present even in middle aged and older males.