4.4: Case Study 1- The Gold Rush

- Page ID

- 21983

British Columbia experienced two big gold rushes, one in 1858 on the Fraser River and the other in 1862 in the Cariboo district, and a number of smaller gold rushes. In each, tens of thousands of men (and a few women) sailed north from California, where the gold rush was coming to an end, to land in Esquimalt Harbour on Vancouver Island, not far from Fort Victoria.

Every miner had to fist travel to Victoria in order to obtain a license to prospect and pan for gold in BC, making the city a services hub for the mining industry. At that time, Fort Victoria was tiny with about 500 immigrants living on southern Vancouver Island. Most of these were Hudson’s Bay Company employees, farmers and their families. Within two months of the news of the discovery of gold in 1858, the population grew to over 20,000. There was little infrastructure for all these new arrivals and Fort Victoria became a tent city as miners camped while they purchased their mining licenses and all their supplies.

Although much of the historical documentation and focus is on the mining for gold during this time, it is also important to note that there was mining happening in other areas, such as coal, oil, natural gas, silver and copper. The expansion of all these other resources occurred after the 1960s when the technology for open pit mining was developed.

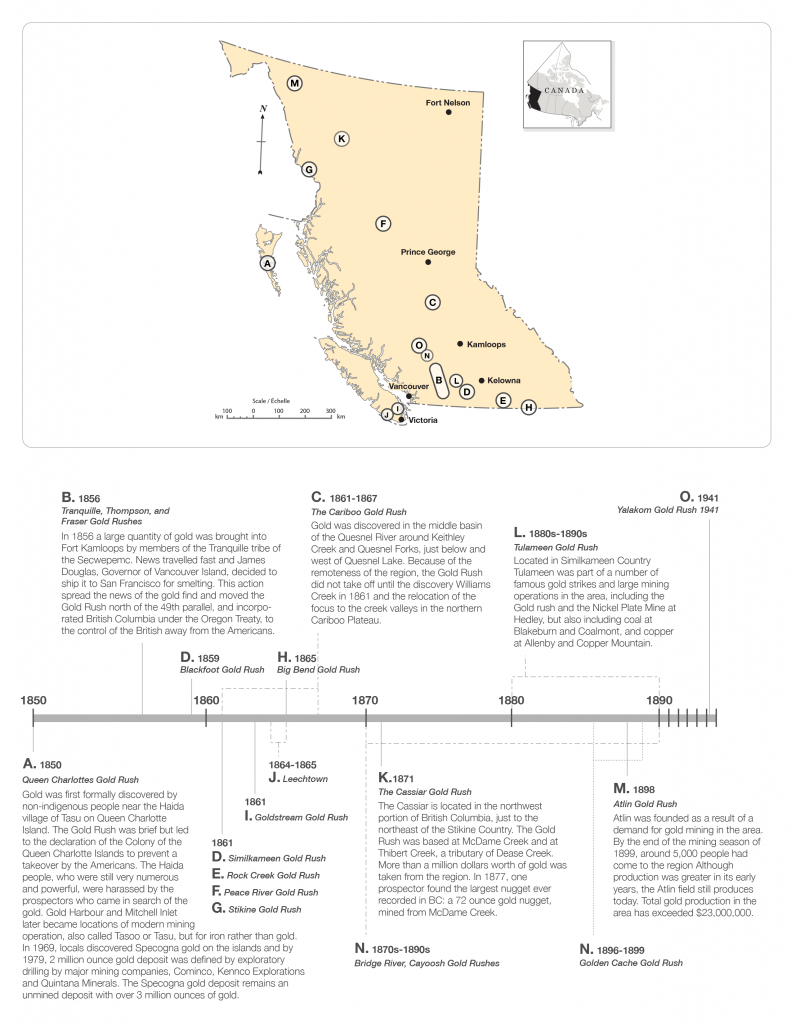

Gold Rush Regions

If you are viewing this on the Web, you can use the interactive map here to learn a little more on each of the regions around BC where gold was discovered and prospecting took place. If you are reading this book in print, the static map shows the regions in a standard map.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://opentextbc.ca/geography/?p=111

View BC gold rush in a larger map

Women and Chinese prospectors during BC’s Gold Rush

Women

Women played an important role in the era of the gold rush. Many women prospectors searched the rivers of BC alongside the men or indeed with their husbands or family. But it was the lack of women that also factored into this era. During the earlier periods of the gold rush, there were so few women in the towns that brides were sent for from other parts of the world. An example is the Anglican minister in Lillooet, Robert C. Brown, who initiated the Columbia Emigration Society with its sole purpose being to arrange for young women from England to be sent to the Cariboo as potential brides for the miners!

Chinese Prospectors

During the Cariboo gold rush the first Chinese community was established in Canada in Barkerville. Discrimination toward Asians prevented the Chinese from prospecting anywhere other than on abandoned sites, and so they did not make as much money as the white prospectors. Despite this discrimination, the Chinese community thrived by providing many of the required services to the 20,000 prospectors who came into the Barkerville region in the 1860s, including operating grocery stores and restaurants. At the height of the gold rush there were as many as 5,000 Chinese living there.

During both the Fraser and Cariboo gold rushes, Chinese immigrants also landed in Fort Victoria, having moved from California to escape the discrimination there, and once the gold rush was over, many stayed on. In Victoria, the Chinese started import businesses and worked as small merchants, building a strong community in the city. The first Chinatown in Canada was founded in Victoria in the 1850s, and by the end of the 1860s there were approximately 7,000 Chinese living in British Columbia.

First Nations during BC’s Gold Rush

In historical accounts of BC’s gold rush, First Nations peoples of the area are overlooked, but they certainly played an important role.

The Aboriginal residents were essential to the prospectors, providing them with goods such as canoes and food, and services such as guides and translators. Both Aboriginals and prospectors benefited from the relationship a the Aboriginals wanted to trade and the prospectors needed the goods and access to local knowledge.

As the number of prospectors increased in the rush to find gold, their own local knowledge grew and the initial mutually beneficial relationship began to collapse. As time went on First Nations people were marginalized and even terrorized on their own lands.

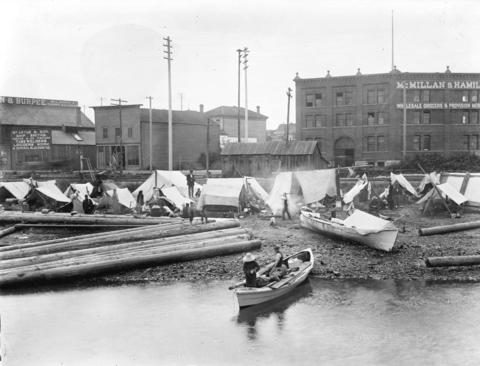

The photograph from 1898 in Figure 4 shows the contrast between the buildings in Vancouver in the background and First Nations peoples attempting to maintain their livelihood on their territory.

Attributions

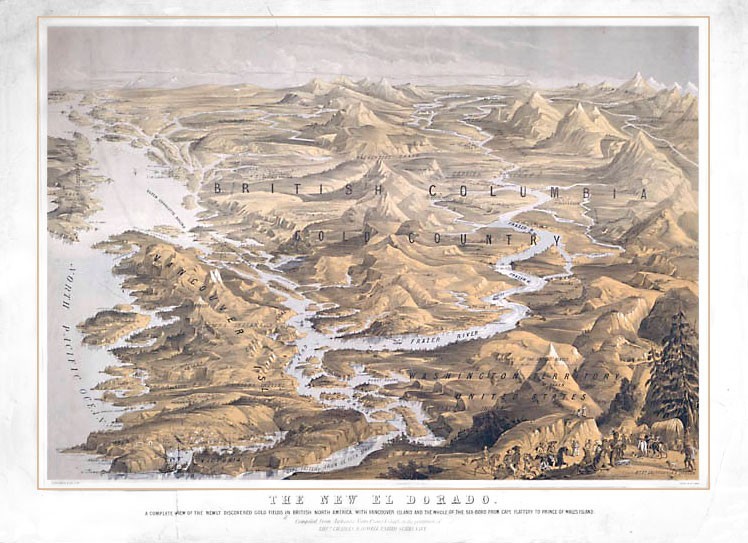

- Figure 4.3 BC as the new El Dorado by Peter Winkworth- Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. R9266-3470 Peter Winkworth Collection of Canadian This image is in the Public Domain and is available from Library and Archives Canada (www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/pam_archives/public_mikan/index.php?fuseaction=genitem.displayItem&lang=eng&rec_nbr=3022666&rec_nbr_list=3022666).

- Figure 4.4 British Columbia gold rush: Regions and timeline created by Hilda Anggraeni

- Figure 4.5 Women panning for Gold by Louis Denison Taylor is in the Public Domain (source: http://searcharchives.vancouver.ca/woman-panning-for-gold)

- Figure 4.6 First Nations people camped on Alexander Street beach at foot of Columbia Street by Major James Skitt Matthews is in the Public Domain (source: http://searcharchives.vancouver.ca/first-nations-people-camped-on-alexander-street-beach-at-foot-of-columbia-street)