4.1: Introduction

- Page ID

- 38659

What is culture? When some people speak of culture, they are thinking of high culture (e.g. ballet or opera). Others may think of current, prominent topics (i.e. pop culture). Academic settings, though, are referring to something else. Culture is a learned behavior and a human construct. Culture exists to answer questions. Some of the questions that are answered are philosophical or ideological, for example, “Where did we come from?” or “What is acceptable behavior?” Other questions revolve around daily life. “How do we secure shelter, clothe ourselves, produce food, and transmit information?” Culture provides us with guidance for our lives. It both asks and answers questions. Children, from an early age, start asking “What is my place in the world?” Culture helps to answer that.

The word culture itself comes the Latin word cultura, meaning cultivation or growing. This is precisely what humans do with both their material and abstract cultural components. Humans, since early childhood, learn to shape, create, share, and change their culture. Culture is the very vehicle we use to navigate through our environments. Culture is a form of communication and it evolves. And as a type of compass, it leads.

4.1.1 Components of Culture

At the most simplistic levels, culture can be either concrete and tangible, or abstract. Either way, culture is used to express identity for both individuals and groups. And whether it is concrete or abstract, again it is a human construct used as a way to create a sense of belonging. People convey culture through various outlets such as festivals, food, and architecture. They are able to meet their worldwide fundamental needs while maintaining individual group qualities. Culture can be classified into three different categories: mentifacts (ideas or beliefs), artifacts (goods or technology), and sociofacts (forms of social organization).

All cultures have underlying beliefs and thought processes. These beliefs include religion (Chapter 6) and language (Chapter 5) but go far beyond that. Other important beliefs include things like nationalism (see Chapter 8), customs orprejudices. These beliefs can be expressed through various avenues, using a variety of auditory, visual, and tactile means. For example, nationalism can be expressed through song, cuisine, dress, and public events. You can hear nationalism in the form of an anthem, see it in the form of a flag, taste it when you eat a dish that represents a group of people, and feel it in the form of a piece of jewelry.

Technology is a human construct. From our earliest inventions (fire, weapons) to a supercomputer, the things that people build are products of their perceived needs, their technical abilities and their available resources. Technology includes clothing, foods and housing. Another name for technology is material culture. Think of material culture as the material that archaeologists study. The materials that we use are often left behind for later people to study, like the clay tablets the Sumerians used to record their writing or the remnants of an Iroquois longhouse used for shared living. Other components of culture (like ideas) leave fewer traces. We can find material culture related to burial practices that date back millennia but may not always have the material evidence to show how people grieve.

Lifestyle is a component of culture that can be overlooked, but it is vitally important. In many cultures, a family is a very large unit and people can tell in great detail their exact relationship to everyone else in a place. In the modern context, a family could consist of a single parent and a child and it is possible to live in a neighborhood filled with unrelated people and not know the name of a single neighbor.

Culture can be seen either through the lens of a microscope or through that of a telescope. Folk culture is local, small and tightly bound to the immediate landscape. Popular culture is large, dispersed, and globalizing. These two forms of culture are not totally separated. They are related and both currently exist in the world. Prior to about 2008, most people on Earth lived in rural communities, often practicing a folk culture. The world as a whole is moving toward popular culture.

4.1.2 Cultural Reproduction

As human beings, we reproduce in two ways: biologically and socially. Physically we reproduce ourselves through having children. However, culture consists solely of learned behavior. In order for culture to reproduce itself, it has to be taught. This is what makes culture a human creation. How is culture transmitted? Human beings are natural mimics. This is the way we learn to speak, and it is the way we learn the rest of our culture as well. We learn through observation and, subsequently, through practice. At another scale, mimicry is the mechanism that drives cultural diffusion. Human beings copy the things we like. The old line “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery,” perfectly describes the human desire to incorporate successful adaptations.

How people have shared culture has changed drastically over time. This can partly be attributed to the channels in which we share culture. In the past, culture was shared orally and in person. Words eventually became written, the written became electronic, and we now have access to things from anywhere at any time.

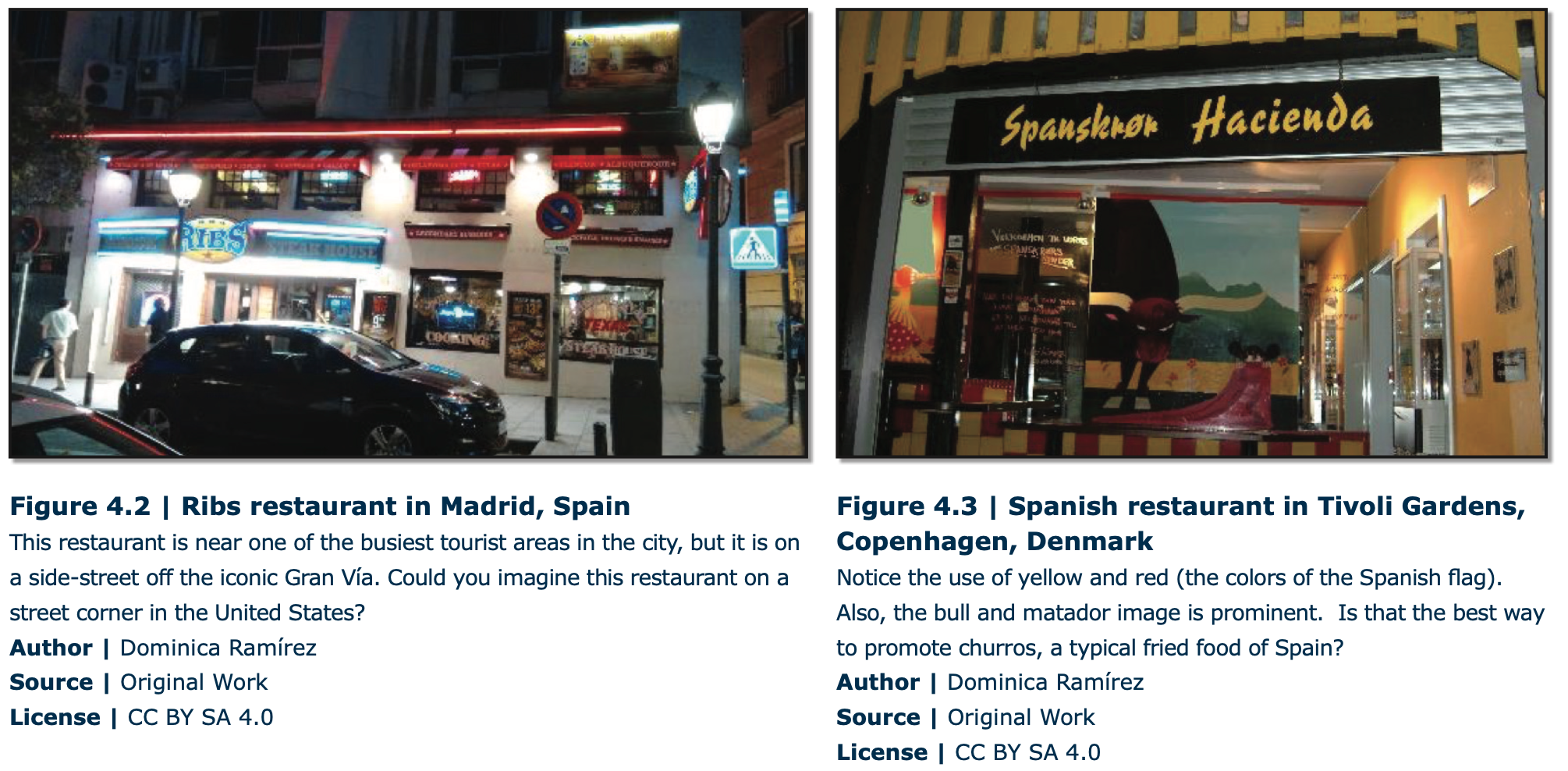

The debate over authenticity has also become a topic of debate. If culture is created, recreated, and is fluid, how can we define authenticity? Has culture become placeless? Placelessness or the irrelevance of place has become a central topic in the contemporary philosophy of geography. Can people have an All-American dining experience in the heart of Madrid, Spain? Can they experience Spanish street-food at a historic theme park in Copenhagen, Denmark? As the following pictures show, icons representing other places are now common in the landscape.

4.1.3 Culture Hearths

Human beings have always had learned behaviors, it’s one of the defining characteristics of human beings. Cultural evolution describes the increasing complexity of human societies over time. Our earliest cultures were simple. Welived in small groups, ranged across fairly large areas, and lived off the natural landscape. Human impact on the environment is less than it is now, but there was an impact. Earlier peoples burned forests to clear land and flush game, and in some places hunted the megafauna to extinction.

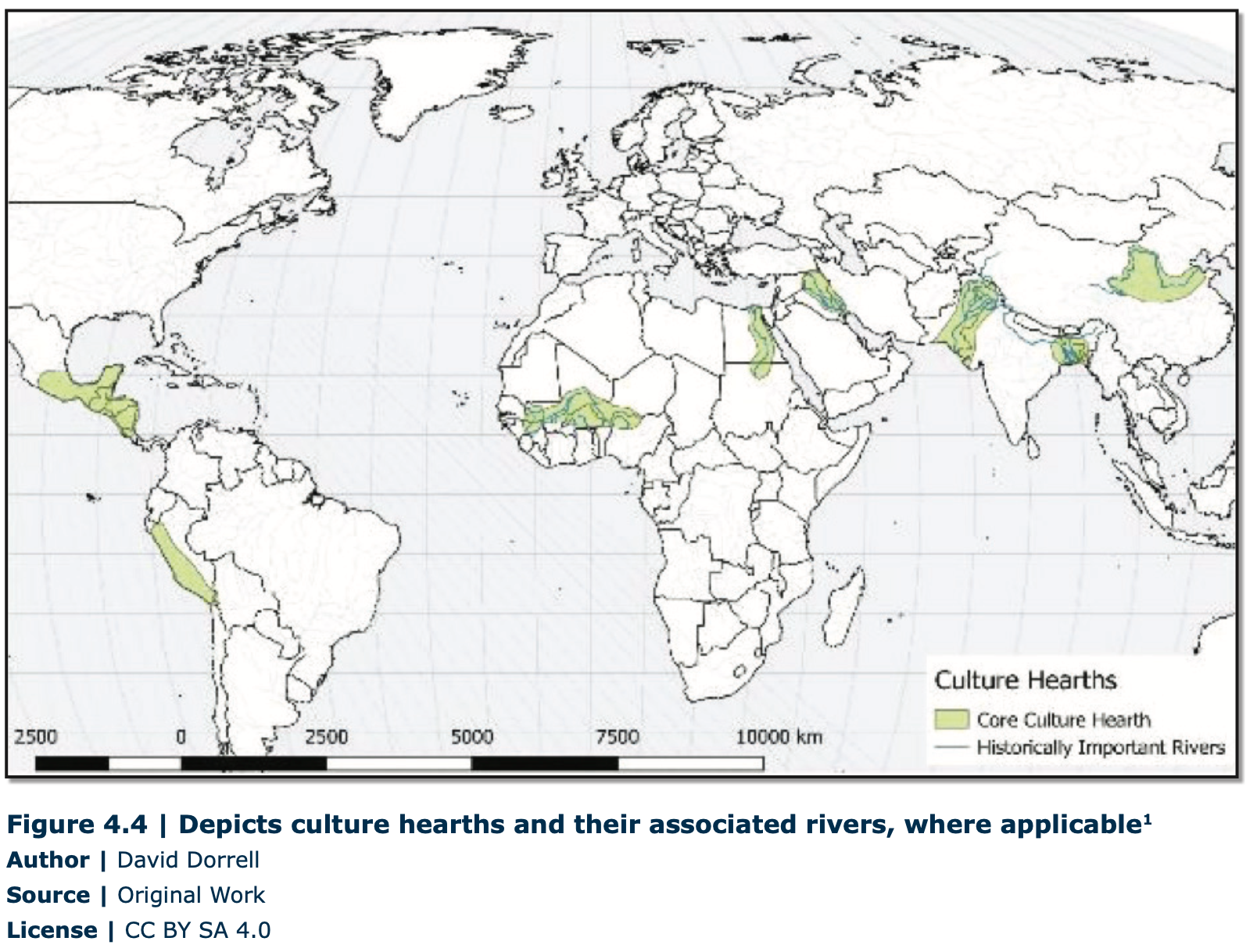

Recognizable cultures have places of origin. The word culture refers to cultivation or growing. We care for something, we nurture an idea as it grows. All cultural elements have a place of origin. Some places have been responsible for a great deal of cultural development. We call these places culture hearths. Culture hearths provided many of the cultural elements (technologies, organizational structures, and ideologies) that would diffuse to other places and later times. Cultural hearths provide operational scripts for societies.

Culture hearths are closely associated with the foods that they domesticated. food is an important cultural element due to the fact that it is both a technology as well as form of expression. Although the preceding map shows areas of ancient civilization, these are not the only places that have contributed to contemporary cultures. Ideas can arise anywhere, but ancient ideas collected in these places.

Cultures incorporate pieces of other cultures. Some recognizable themes in creation myths are stories of great floods or other cataclysmic events, and these types of stories recycled through history. Languages without writing will often reuse another language’s writing system. Once again, desirable characteristics get copied.