12.3: Urbanization

- Page ID

- 38717

12.3.1 Urban Origins

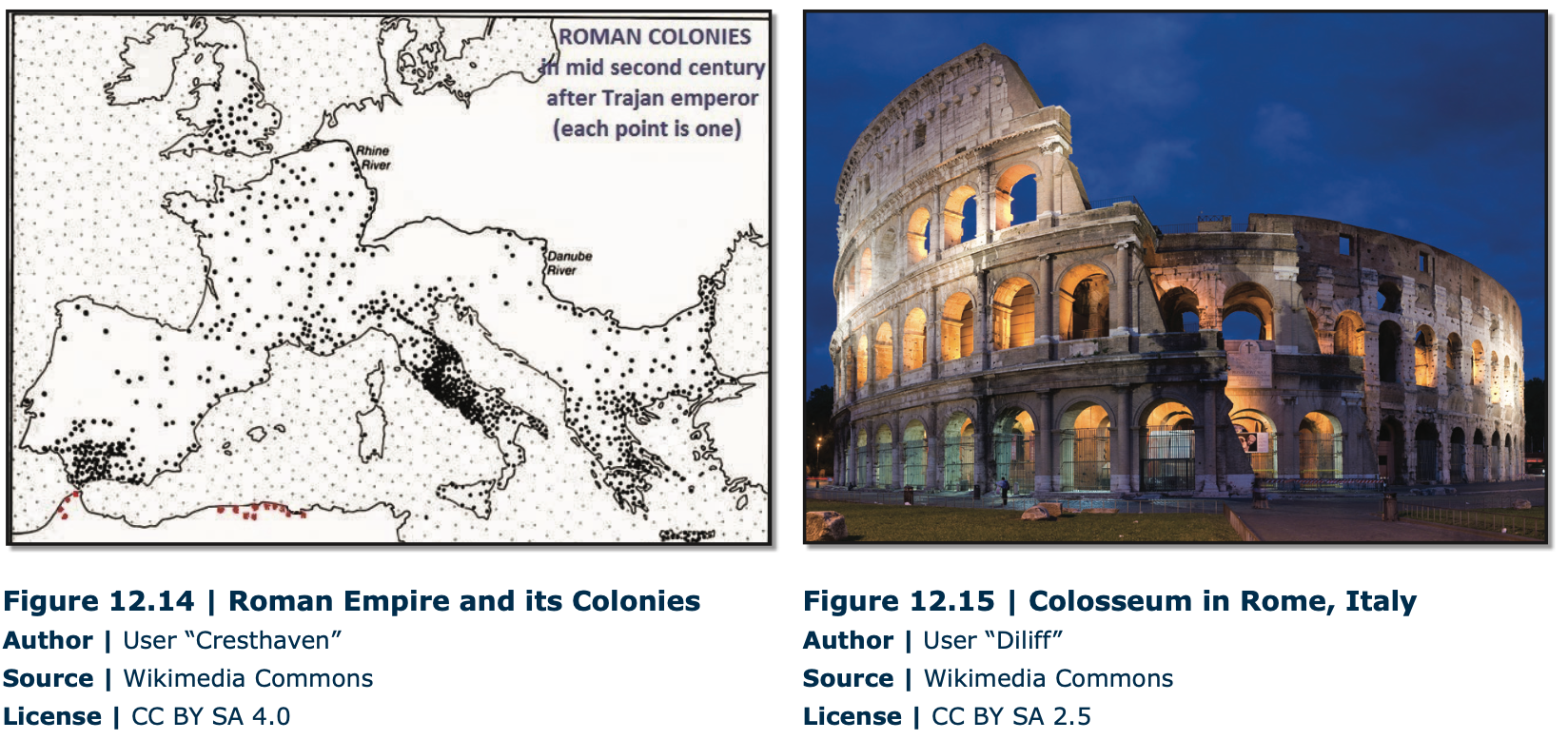

The earliest towns and cities developed independently in the various regions of the world. These hearth areas have experienced their first agricultural revolution, characterized by the transition from hunting and gathering to agricultural food production. Five world regions are considered as hearth areas, providing the earliest evidence for urbanization: Mesopotamia and Egypt (both parts of the Fertile Crescent of Southwest Asia), the Indus Valley, Northern China, and Mesoamerica (Figure 12.9). Over time, these five hearths produced successive generations of urbanized world-empires, followed by the diffusion of urbanization to the rest of the world.

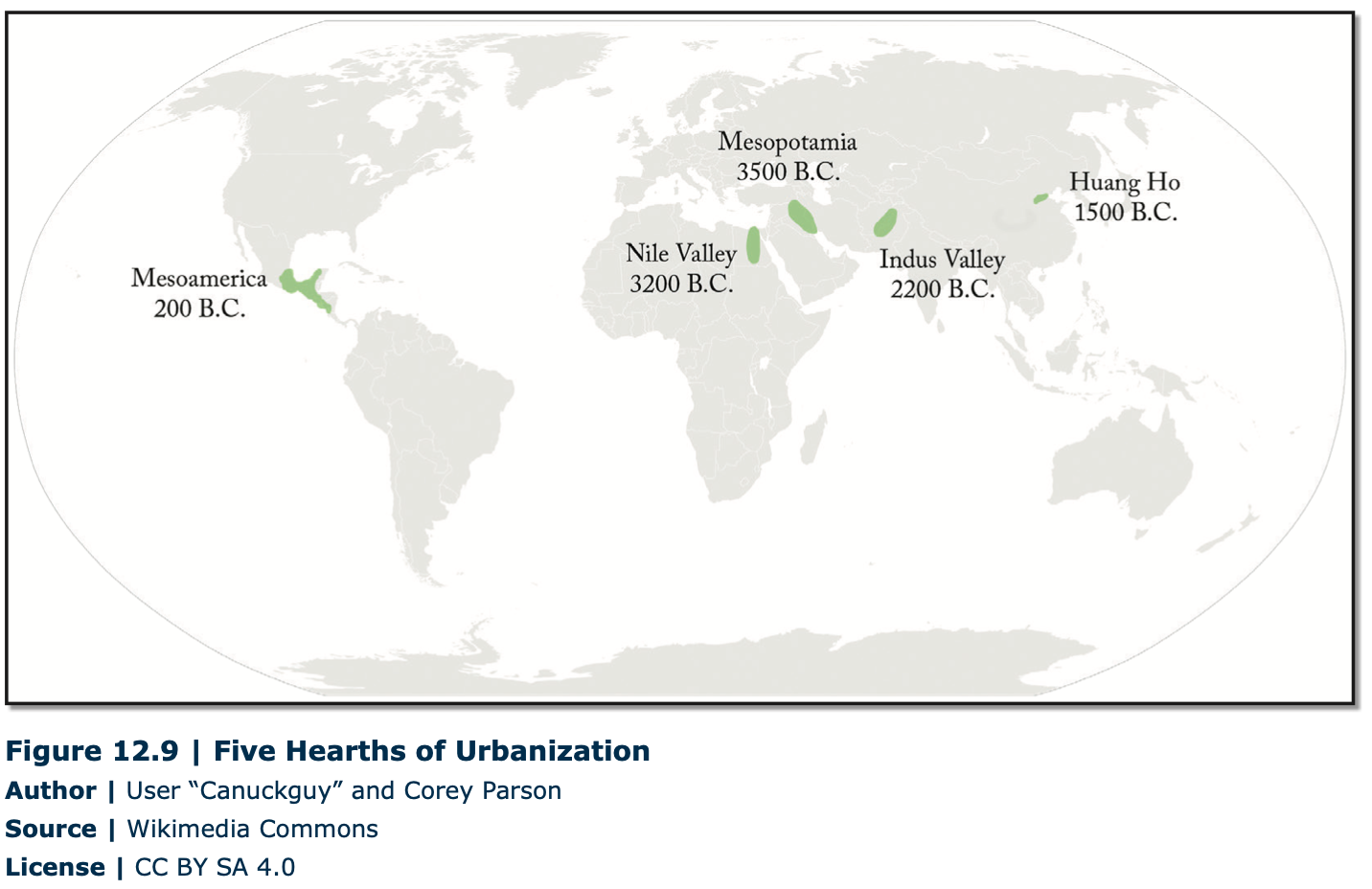

The first regions of independent urbanism were in Mesopotamia and Egypt from around 3500 B.C. Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, was the eastern part of the so-called Fertile Crescent (Figure 12.10). From the Mesopotamian Basin, the Fertile Crescent stretched in an arc across the northern part of the Syrian Desert as far west as Egypt, in the Nile Valley. In Mesopotamia, the significant growth in size of some of the agricultural villages formed the basis for the large fortified citystates of the Sumerian Empire such as Ur, Uruk, Eridu, and Erbil, in present-day Iraq. By 1885 B.C., the Sumerian city-states had been taken over by the Babylonians, who governed the region from Babylon, their capital city. Unlike in Mesopotamia, internal peace in Egypt determined no need for any defensive fortification. Around 3000 B.C. the largest Egyptian city was probably Memphis (over 30,000 inhabitants). Yet, between 2000 and 1400 B.C., urbanization continued with the founding of several capital cities such as Thebes and Tanis.

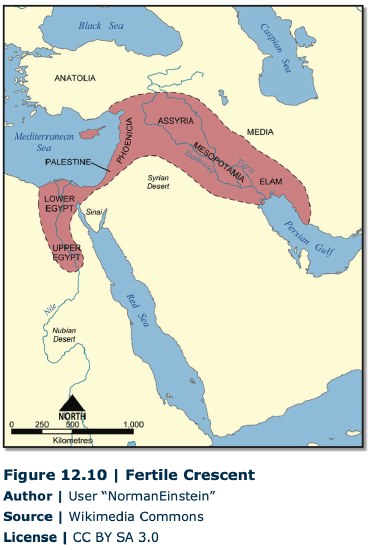

About 2500 B.C, large urban settlements were developed in the Indus Valley (Mohenjo-Daro, especially), in modern Pakistan, and later, about 1800 B.C., in the fertile plains of the Huang He River (or Yellow River) in Northern China, supported by the fertile soils and extensive irrigation systems. Other areas of independent urbanism include Mesoamerica (Zapotec and Mayan civilizations, in Mexico) from around 100 B.C. and, later, Andean America from around A.D. 800 (Inca Empire, from northern Ecuador to central Chile). Teotihuacan (Figure 12.11), near modern Mexico City, reached its height with about 200,000 inhabitants between A.D. 300 and 700.

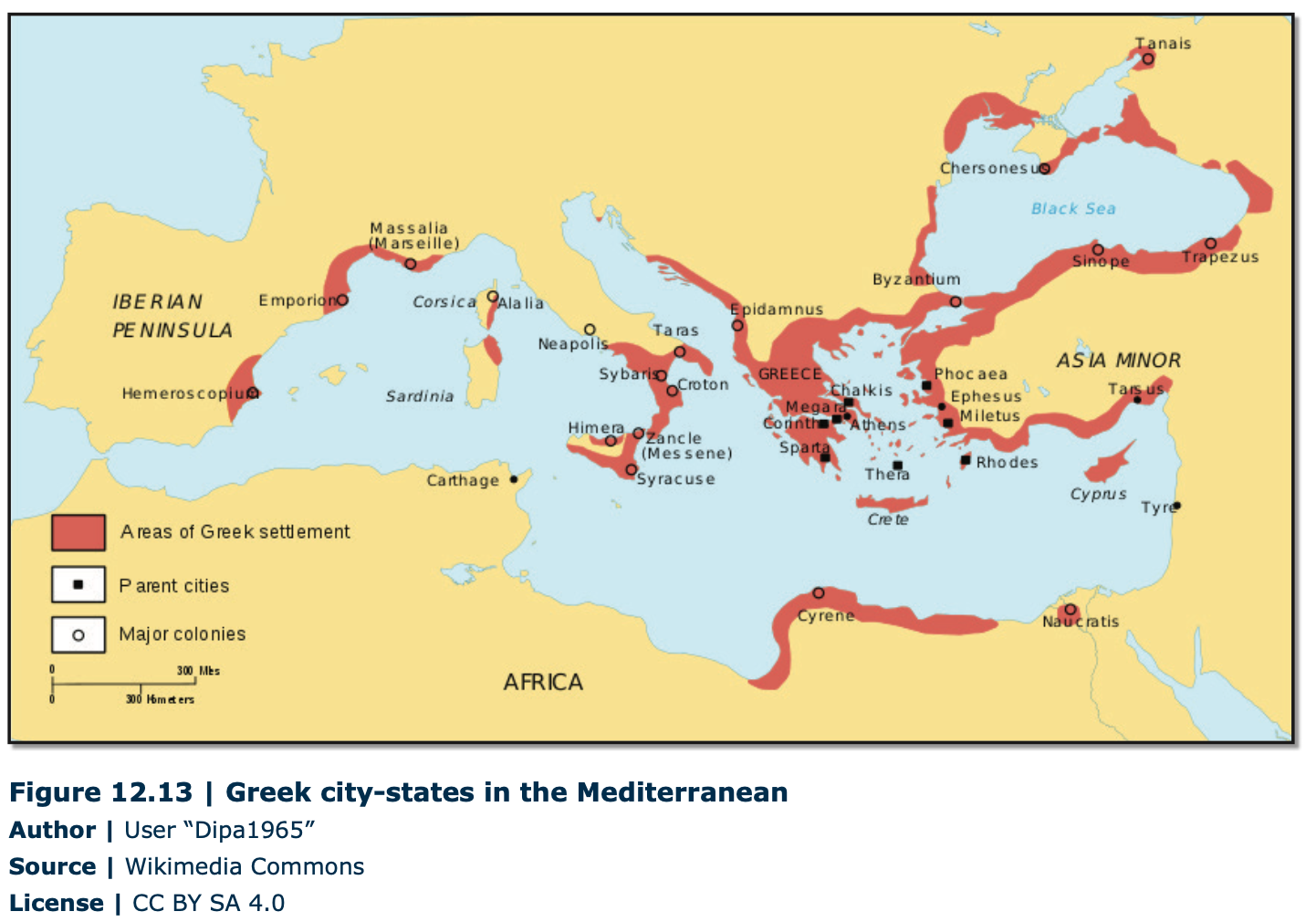

The city-building ideas eventually spread into the Mediterranean area from the Fertile Crescent. In Europe, the urban system was introduced by the Greeks, who, by 800 B.C., founded famous cities such as Athens, Sparta, and Corinth. The city’s center, the “acropolis,” (Figure 12.12), was the defensive stronghold, surrounded by the “agora” suburbs, all surrounded by a defensive wall. Except for Athens, with approximately 150,000 inhabitants, the other Greek cities were quite small by today’s standards (10,000-15,000 inhabitants). The Greek urban system, through overseas colonization, stretched from the Aegean Sea to the Black Sea, around the Adriatic Sea, and continued to the west until Spain (Figure 12.13).Although the Macedonians conquered Greece during the 4th century BC, Alexander the Great extended the Greek urban system eastward toward Central Asia. The location of the cities along Mediterranean coastlines reflects the importance of long-distance sea trade for this urban civilization.

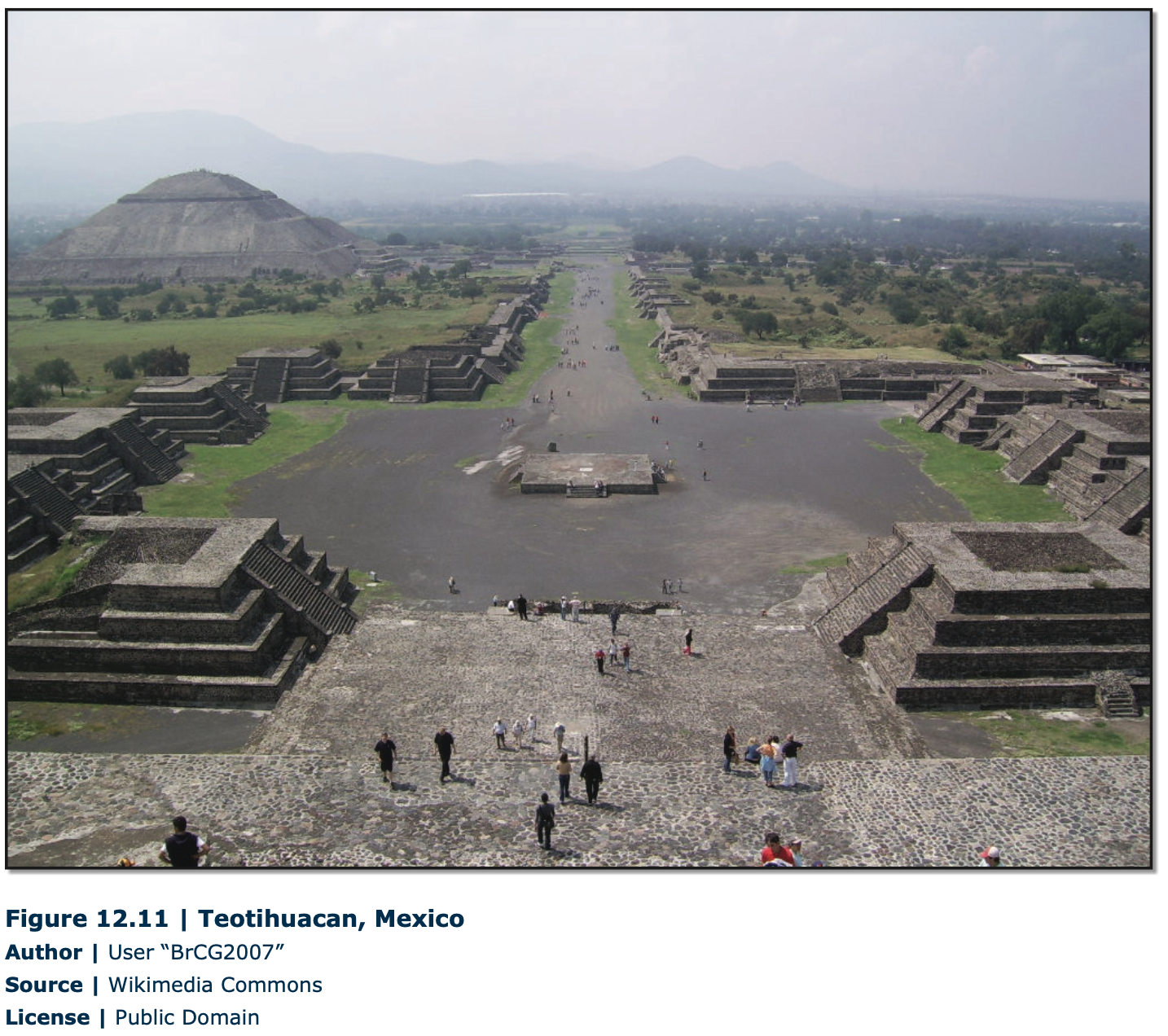

With the impressive feats of civil engineering, the Romans had extended towns across southern Europe (Figure 12.14), connected with a magnificent system of roads. Roman cities, many of them located inland, were based on the grid system. The center of the city, “forum,” surrounded by a defensive wall, was designated for political and commercial activities. By A.D. 100, Rome reached approximately one million inhabitants, while most towns were small (2,000-5,000 inhabitants). Unlike Greek cities, Roman cities were not independent, functioning within a wellorganized system centered on Rome. Moreover, the Romans had developed very sophisticated urban systems, containing paved streets, piped water and sewage systems and adding massive monuments, grand public buildings (Figure 12.15), and impressive city walls. In the 5th century, when Rome declined, the urban system, stretching from England to Babylon, was a well-integrated urban system and transportation network, laying the foundation for the Western European urban system.

With the impressive feats of civil engineering, the Romans had extended towns across southern Europe (Figure 12.14), connected with a magnificent system of roads. Roman cities, many of them located inland, were based on the grid system. The center of the city, “forum,” surrounded by a defensive wall, was designated for political and commercial activities. By A.D. 100, Rome reached approximately one million inhabitants, while most towns were small (2,000-5,000 inhabitants). Unlike Greek cities, Roman cities were not independent, functioning within a wellorganized system centered on Rome. Moreover, the Romans had developed very sophisticated urban systems, containing paved streets, piped water and sewage systems and adding massive monuments, grand public buildings (Figure 12.15), and impressive city walls. In the 5th century, when Rome declined, the urban system, stretching from England to Babylon, was a well-integrated urban system and transportation network, laying the foundation for the Western European urban system.

12.3.2 Dark Ages

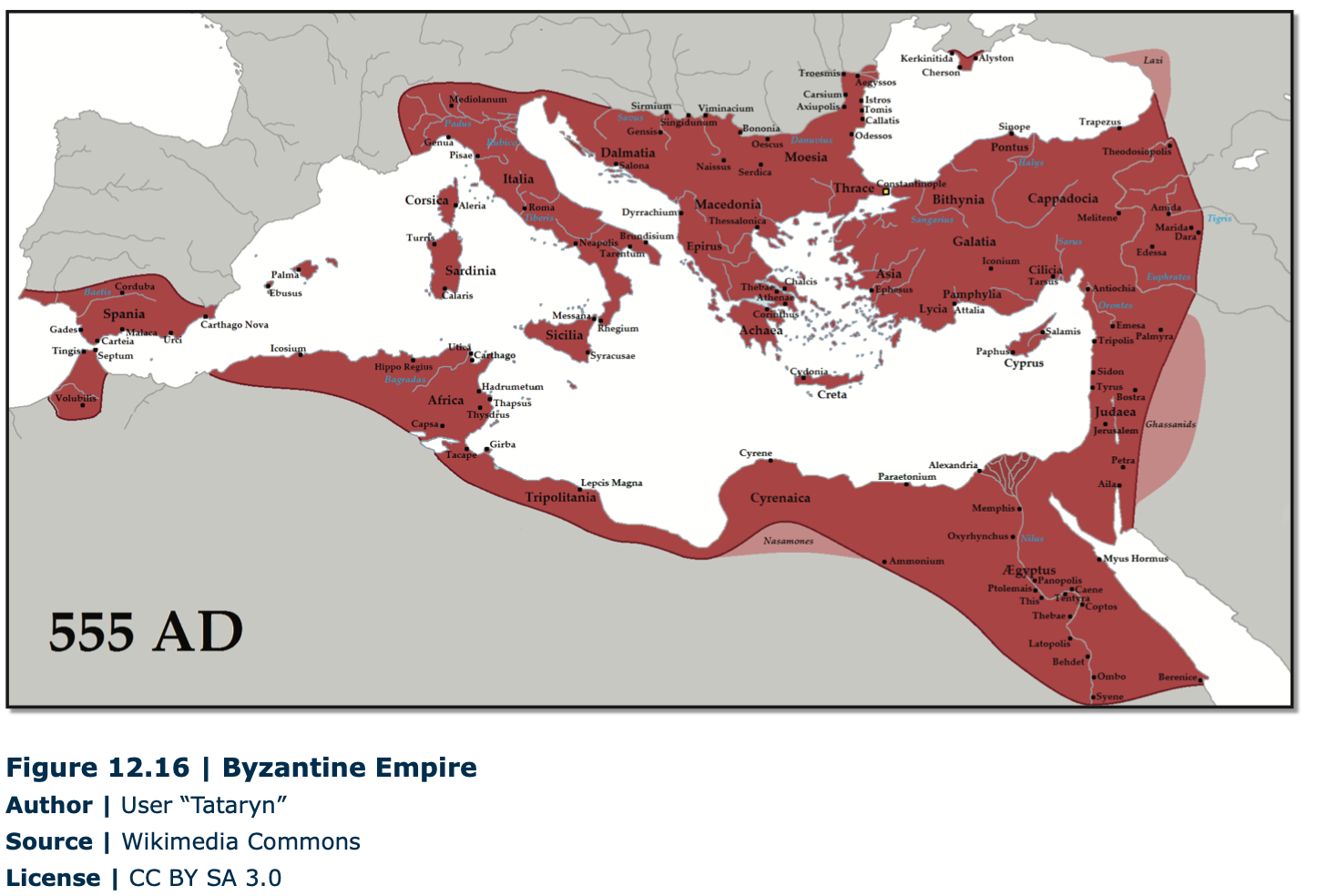

Although urban life continued to flourish in some parts of the world (Middle East, North and sub-Saharan Africa), Western Europe recorded a decline in urbanization after the collapse of the Roman Empire in the fifth century. Duringthis early medieval period, A.D. 476-1000, also known as the Dark Ages, feudalism was a rurally oriented form of economic and social organization. Yet, under Muslim influence in Spain or under Byzantine control, urban life was still flourishing. As Rome was falling into decline, Constantine the Great moved the capital of the Roman Empire to Byzantium, renaming the city Constantinople (current Istanbul, Turkey). With its strategic location for trade, between Europe and Asia, Constantinople became the world’s largest city, maintaining this status for most of the next 1000 years (Figure 12.16).

Most European regions, however, did have some small towns, most of which were either ecclesiastical or university centers (Cambridge, England and Chartres, France), defensive strongholds (Rasnov, Romania), gateway towns (Bellinzona, Switzerland), or administrative centers (Cologne, Germany). The most important cities at the end of the first millennium were the seats of the world-empires/ kingdoms: the Islamic caliphates, the Byzantine Empire, the Chinese Empire, and Indian kingdoms.

12.3.3 Urban Revival in Europe

From the 11th century onward, a more extensive money economy developed. The emerging regional specializations and trading patterns provided the foundations for a new phase of urbanization based on merchant capitalism. By 1400, long distance trading was well established based not only on luxury goods but also on metals, timber, and a variety of agricultural goods. At that time, Europe had about 3000 cities, most of them very small. Paris, with about 275,000 people was the dominant European city. Besides Constantinople (Byzantium) and Cordoba (Spain), only cities from northern Italy (Milan, Florence), and Bruges (Belgium) had more than 50,000 inhabitants.

Between the 14th and 18th centuries, fundamental changes occurred that transformed not only the cities and urban systems of Europe but also the entire world economy. Merchant capitalism increased in scale and the Protestant Reformation and scientific revolution of the Renaissance stimulated economic and social reorganization. Overseas colonization allowed Europeans to shape the world’s economies and societies. Spanish and Portuguese colonists were the first to extend the European urban system to the world’s peripheral regions. Between 1520 and 1580 Spanish colonists established the basis of a Latin American urban system. Centralization of political power and the formation of national states during the Renaissance determined the development of more integrated national urban systems.

12.3.4 Industrial Revolution and Urbanization

Although the urbanization process had already progressed significantly by the 18th century, the Industrial Revolution was a powerful factor accelerating further urbanization, generating new kinds of cities, some of them recording an unprecedented concentration of population. Manchester, for example, was the shock city of European industrialization in the 19th century, growing from a small town of 15,000 inhabitants in 1750 to a world city by 1911 with 2.3 million. Industrialization spread from England to the rest of Europe during the first half of the 19th century and then to different parts of the world. Moreover, followed by successive innovations in transport technology, urbanization increased at a faster pace. The canals, railroads, and steam-powered transportation reoriented urbanization toward the interior of the countries. In North America, the shock city was Chicago, which grew from 4,200 inhabitants in 1837 to 3.3 million in 1930. Its growth as an industrial city followed especially the arrival of the railroads, which made the city a major transportation hub. In the 20th century, the new innovations significantly helped urban development.

By the 19th century, urbanization had become an important dimension of the world-system. The higher wages and greater opportunities in the cities (industry, services) transformed them into a significant pull factor, attracting a massive influx of rural workers. Consequently, the percentage of people living in cities increased from 3 percent in 1800 to 54 percent in 2017.3 In developed countries, 78 percent live in urban areas, compared with 49 percent in developing countries, reflecting the region’s and/or the country’s level of development.

12.3.5 City-Size Distribution

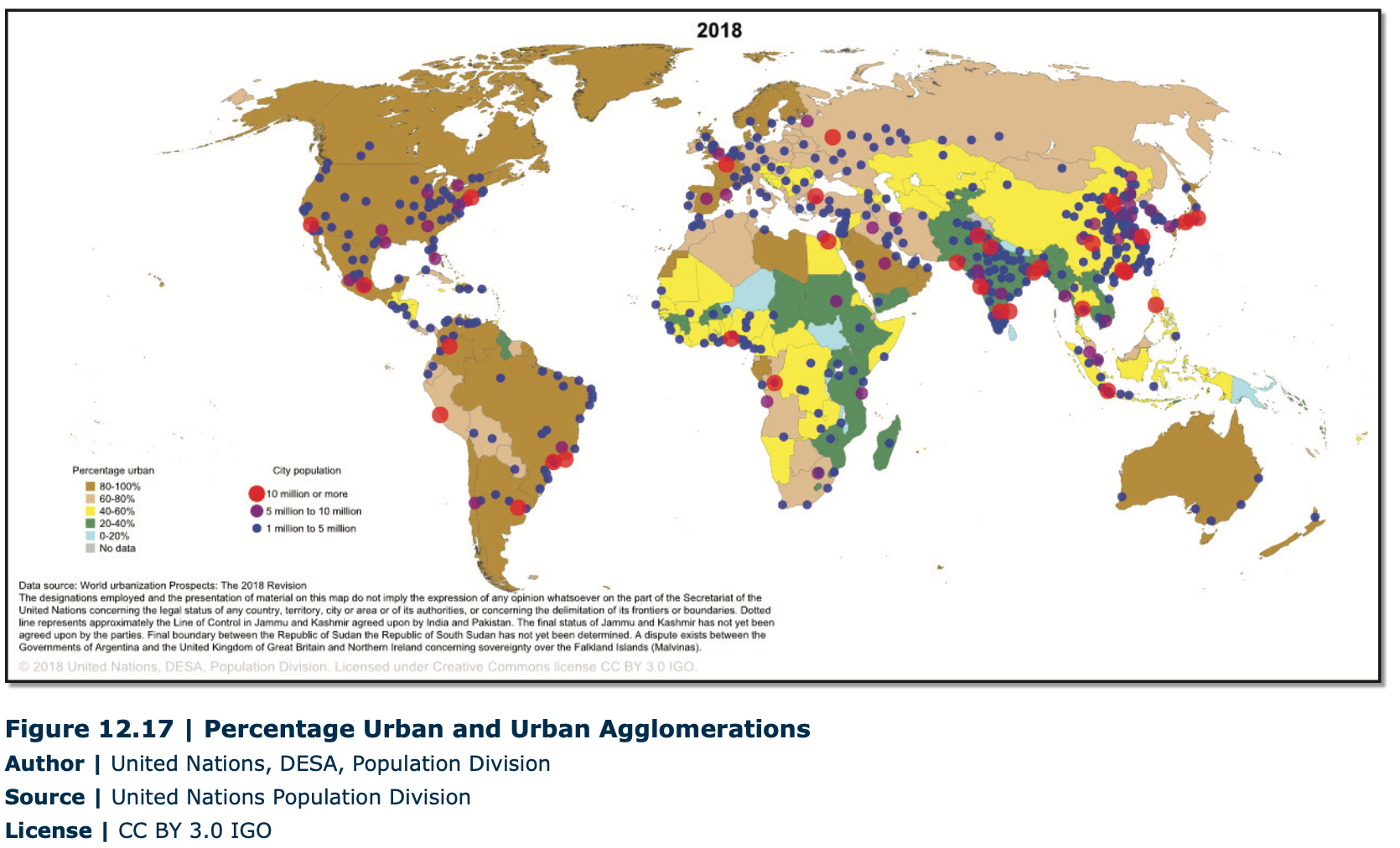

Most developed countries have a higher percentage of urban people, but developing countries have more of the very large urban settlements (Table 1, Figure 12.17). In 1950, out of the world’s 30 largest metropolitan areas, the first three metropolitan areas were in developed countries: New York (U.S.), Tokyo (Japan), and London (UK), two of which (New York and Tokyo) had more than 10 million inhabitants. After 30 years, in 1980, a significant change was recorded. Although metro New York increased from 12.3 million to 15.6 million, Tokyo, with 28.5 million inhabitants, became the largest metropolitan area in the world, a position which the city still maintains. In addition, except for Osaka, the second metropolitan area from Japan, two large metropolitan areas in developing countries were added, Mexico City (Mexico) and Sao Paulo (Brazil). The number of large metropolitan areas continued to increase after 2010, adding more developing countries such as India (Delhi and Mumbai/Bombay), China (Shanghai and Beijing), Bangladesh (Dhaka), and Pakistan (Karachi) from Asia; and Egypt (Cairo), Nigeria (Lagos), and Democratic Republic of the Congo (Kinshasa) from Africa. Each of these metropolitan areas is expected to have over 20 million inhabitants after 2020, adding Delhi and Shanghai to the largest metropolitan areas with over 30 million inhabitants. In the United States, New York-Newark is the largest metropolitan area, in which the population was constantly increasing from 12.3 million in 1950 to 15.6 million in 1980 and 18.3 million in 2010, having the potential to reach 20 million in 2030. Yet, unlike the developing countries, characterized by a very fast urban growth rate, the developed countries had recorded a moderate urban growth rate.

Table 12.1 | The World’s 30 Largest Metropolitan Areas, Ranked by Population Size4

1950, 1980, 2010, 2020, 2025, 2030 (in millions)

|

1950 |

1980 |

2010 |

2020 |

2025 |

2030 |

|

|

World |

New York-12.3 Tokyo-11.2 London-8.3 |

Tokyo-28.5 Osaka-17.0 |

Tokyo-36.8 Delhi-21.9 Mexico City-20.1 Shanghai-19.9 Sao Paulo-19.6 Osaka-19.4 Bombay-19.4 New York- Newark-18.3 Cairo-16.9 Beijing-16.1 |

Tokyo-38.3 Delhi-29.3 Shanghai-27.1 Beijing-24.2 Bombay-22.8 Sao Paulo-22.1 Mexico City-21.8 Dhaka-20.9 Cairo-20.5 Osaka-20.5 |

Tokyo-37.8 Delhi-32.7 Shanghai-29.4 Beijing-26.4 Bombay-25.2 Dhaka-24.3 Mexico City-22.92 Sao Paulo-22.90 Cairo-22.4 Karachi-22.01 Osaka-20.3 Lagos-20.03 |

Tokyo-37.19 Delhi-36.06 Shanghai-30.7 Bombay-27.8 Beijing-27.7 Dhaka-27.3 Karachi-24.8 Cairo-24.5 Lagos-24.2 Mexico City-23.8 Sao Paulo-23.4 Kinshasa-20.00 |

|

United States |

New YorkNewark-12.3 Chicago-5.0 Los Angeles- Long Beach- Santa Ana 4.0 Philadelphia 3.1 Detroit 2.7 Boston 2.5 San FranciscoOakland-1.8 |

New YorkNewark-15.6 Los AngelesLong BeachSanta Ana-9.5 Chicago-7.2 Philadelphia-4.5 |

New YorkNewark-18.3 Los AngelesLong BeachSanta Ana-12.1 |

New YorkNewark-18.7 Los Angeles- Long BeachSanta Ana-12.4 |

New YorkNewark-19.3 Los Angeles- Long BeachSanta Ana-12.8 |

New YorkNewark-19.89 Los Angeles- Long BeachSanta Ana13.26 |

|

Summary: |

|||||||

|

Year |

1 5 mil |

5 10 mil |

10 15 mil |

15 20 mil |

20 25 mil |

25 30 mil |

> 30 mil |

|

1950 |

22 |

6 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

1980 |

6 |

19 |

2 |

2 |

- |

1 |

- |

|

2010 |

- |

7 |

13 |

7 |

2 |

- |

1 |

|

2020 |

- |

- |

12 |

8 |

7 |

2 |

1 |

|

2025 |

- |

- |

10 |

8 |

7 |

3 |

2 |

|

2030 |

- |

- |

10 |

8 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

The relationship between the size of cities and their rank within an urban system is known as rank-size rule, describing a regular pattern in which the nth-largest city in a country or region is 1/n the size of the largest city. According to the rank-size rule, the second-largest city is one-half the size of the largest, the third-largest city is one-third the size of the largest city, and so on. In the United States, the distribution of settlements closely follows the rank-size rule, but in other countries, the population of the largest city is disproportionately large in relation to the secondand third-largest city in that urban system. These cities are called primate cities (Buenos Aires, for example, is 10 times larger than Rosario, the second largest city in Argentina). Yet, cities do not necessarily have to be primate in order to be functionally dominant (economic, political, cultural) within their urban system. The functional dominance of the city is called centrality. Moreover, some of the largest metropolises, closely integrated within the global economic system and playing key roles beyond their own national boundaries, qualify as world cities. Today, because of the importance of their financial markets and associated business services, London, New York, and Tokyo dominate Europe, the Americas, and Asia, respectively.