6.5: Chapter 40- American Budget Priorities

- Page ID

- 73481

Categories of Federal Spending

We can better understand the federal bureaucracy if we understand that it is through those agencies that the United States spends its tax revenue. Where does the money go? There are numerous ways to analyze the federal budget. Perhaps the easiest to understand is to use figures from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and break federal spending down into just three categories, with some subcategories therein: (1)

Mandatory Spending—Mandatory spending refers to programmatic spending that is essentially automatic. Congress sets eligibility requirements and benefit formulas. If you meet the eligibility requirements, you are entitled to receive the benefit according to the formula. That’s why this category is also referred to as entitlement spending. Mandatory spending is the largest overall category of government spending and it has been growing due to factors such as increases in medical costs that affect the budgets for Medicare and Medicaid. Mandatory spending can be broken down into the following buckets:

- Social Security—About 24 cents of every federal dollar go to the Social Security program. It is primarily a program to fight poverty among the elderly, although it has other components such as the Supplemental Security Income program to assist the blind and disabled. Through payroll deductions, workers pay into the system to support people who are currently retired—look for something that says FICA on your paycheck. In turn, current workers will be supported by today’s children when they enter the workforce.

- Medicare—About 15 cents of every federal dollar go to the Medicare program, which provides health insurance for retired people. This is necessary because the American health insurance system primarily relies on employer-based health insurance, which people lose when they retire.

- Medicaid—About 9 cents of every federal dollar go to the Medicaid program, which provides health insurance for people who fall below certain income levels.

- Other—The United States has many other mandatory spending programs. About 13 cents of every federal dollar go to fund programs like unemployment compensation, military retirement, veterans’ benefits, food stamps, and the earned income tax credit.

Discretionary Spending—Discretionary spending refers to federal spending that changes year to year as Congress passes appropriation bills funding particular agencies. Presidents make proposals to Congress for what they’d like to see spent, and each congressional chamber has its own budget committees. However, it is widely recognized across the political spectrum that the congressional budget process has been broken for a long time, with Congress routinely passing stopgap measures and continuing resolutions to keep the government open. (2) Given that dysfunctional context, discretionary spending falls into two categories:

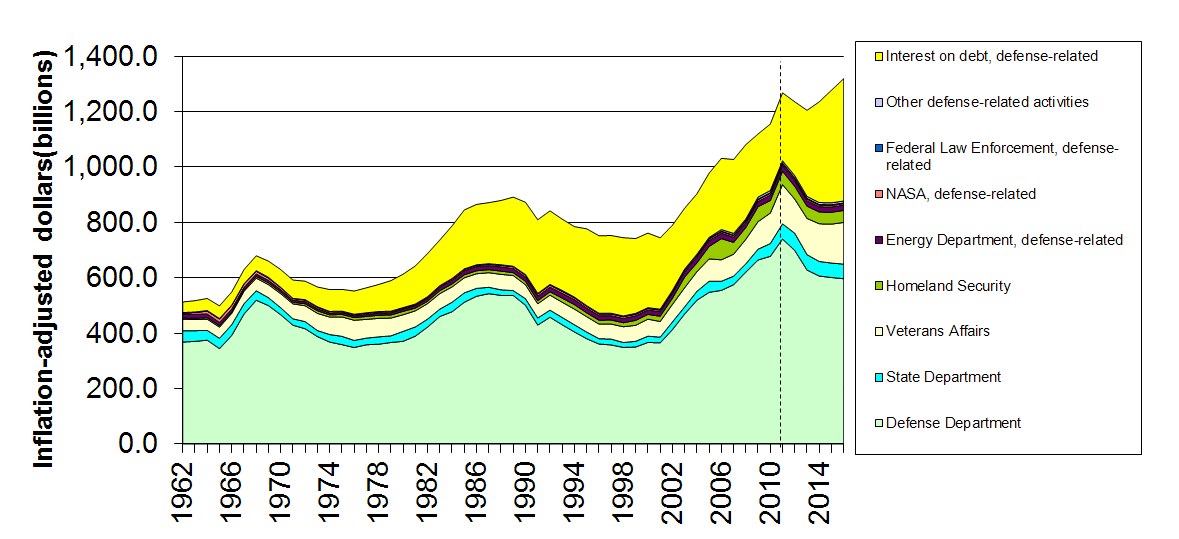

- Defense Spending—About 14 cents of every federal dollar go to fund the Department of Defense. Defense spending is a misleadingly low number for two reasons. First, much defense-related spending is counted as nondefense spending. For example, spending for nuclear weapons development is not counted here because it occurs under the auspices of the Department of Energy. Similarly, military veteran spending falls into the non-defense category even though it is supporting the American military superstructure. Some spending in the Department of Homeland Security is defense-like but is counted as non-defense spending. Spending on the intelligence agencies is also not counted as defense spending. The second reason that defense spending is not fully accurate is due to the fact that the United States sometimes treats its active war-fighting money as “off budget.” For example, the George W. Bush administration took most of the war spending for the Iraq and Afghanistan invasions off budget to make budget deficits look smaller than they actually were and to avoid stirring up opposition to the war. (3) This is also a good place to note that the Department of Defense has never passed an audit, which was required of all federal agencies in 1990. (4)

- Nondefense Spending—About 14 cents of every federal dollar go to non-defense spending. When we consider that some of this spending is really defense spending, we realize that non-defense discretionary spending is a surprisingly small portion of federal spending. This money goes to support all of the things that pop into people’s heads when we think of government—the National Park Service, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Internal Revenue Service, the Department of Education, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the National Weather Service, etc. These agencies are often given enormous regulatory and enforcement mandates without the resources they need. For example, the National Taxpayer Advocate report to Congress says that the Internal Revenue Service does not have adequate resources nor does it have the kind of modern and robust IT infrastructure it needs to do its job well. (5) To cite another example, the National Park Service budget has barely increased in the past two decades while visits to national parks have exploded, and deferred maintenance keeps piling up—even as national parks provide an estimated $100 billion in annual benefits to the American people. (6)

Interest on the Debt—Because the federal government fails to take in enough tax revenue to cover its spending, every year we spend hundreds of billions of dollars to service our debt—that is, we pay interest to wealthy people, institutional investors, and banks who lend the U.S. government money by buying Treasury bonds. Interest on the debt accounts for nearly 10 cents of every one dollar the U.S. government spends. Interest on the debt represents an interesting and sad revenue transfer from the middle class to the wealthy. Robert Reich, the former Secretary of Labor and public policy professor, points out that tax rates for wealthy families and corporations used to be higher than they are today, and the government generally did not run a significant deficit. What we’ve done since the 1950s is to reduce taxes on the wealthy and on corporations and increase the annual deficit, and then we’ve turned to those very wealthy individuals and corporations to lend the government money, for which they get a safe and secure return on their investment. What’s happening, says Reich, is that “the government pays the rich interest on a swelling debt, caused largely by lower taxes on the rich.” The middle class is providing a nice subsidy to the wealthy via the interest on the federal debt. (7)

What If?

References

- Office of Management and Budget Fiscal 2019 Budget.

- For example, Erica Werner, “Senate Passes Stopgap Spending Bill to Keep Government Open through Nov 21, Sending Measure to Trump,” Washington Post. September 26, 2019. For good diagnoses of the ills of the budget process as well as suggestions to improve it, see the material put out by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

- Michael Boyle, “How the U.S. Public Was Defrauded by the Hidden Cost of the Iraq War,” The Guardian. March 11, 2013.

- Courtney Bublé, “Defense Department Fails Its Second Audit, Yet is Making Progress,” Government Executive. November 18, 2019.

- National Taxpayer Advocate, Annual Report to Congress 2019.

- Linda J. Bilmes and John B. Loomis, editors, Valuing U.S. National Parks and Programs: America’s Best Investment. New York: Routledge, 2019.

- Robert Reich, “The Middle Class Pay for the Government. The One Percent Profit From It,” Newsweek. February 11, 2020.

- David Cay Johnston, “The True Cost of National Security,” Columbia Journalism Review. January 31, 2013. William Hartung and Mandy Smithburger, “Boondoggle, Inc.: Making Sense of the $1.25 Trillion National Security State Budget,” Counterpunch. May 9, 2019.

- Chris Salcedo, “Stop Overspending on the F-35,” Townhall. September 9, 2019. Mike Stone, “Pentagon Announces F-35 Jet Prices for Next Three Years,” U.S. News and World Report. October 29, 2019.

- FY 2021 Budget Proposal for the Department of Health and Human Services. Budget for CDC on page 43.

- Dave Lindorff, “Truly Remaking Social Security is the Key to Having a Livable Society in the US,” Counterpunch. February 19, 2020.

Media Attributions

- InflationAdjustedDefenseSpending © Johnpseudo is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license