4.5: Voting and Citizen Participation

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 128425

- Robert W. Maloy & Torrey Trust

- University of Massachusetts via EdTech Books

Standard 4.5: Voting and Citizen Participation in the Political Process

Describe how a democracy provides opportunities for citizens to participate in the political process through elections, political parties and interest groups. (Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for History and Social Studies) [8.T4.5]

FOCUS QUESTION: How have Americans' right and opportunities to vote changed over time?

Democracies depend on the active and informed involvement of their members, or what Standard 4.5 calls "citizen participation in the political process." If only a limited number of people participate, then democracy gives way to a system of government where elites, powerful special interests, and unrepresentative coalitions make decisions for everyone else.

You can go here for a visual timeline of the History of Voting in America from the Office of the Secretary of State of the state of Washington.

See also Voting Rights: A Short History from the Carnegie Corporation of New York (2019).

This voting timeline sets the stage for two major major voting rights bills that have been introduced in Congress following the 2020 Presidential election and the January 6, 2021 insurrection at the Capitol: the For the People Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act.

The For the People Act protects the right to vote, ends partisan gerrymandering, reduces the influence of corporate money in elections, and establishes new ethics rules for elected officials. The John Lewis Act restores the power of the Department of Justice to prevent states from restricting people's right to vote. In congressional votes in 2021, both were unanimously supported by Democrats and unanimously opposed by Republicans.

Who Do Voters Vote For?

How many elected officials do people vote for in the United States? The number may surprise you.

Besides one President, 100 senators and 435 members of the House of Representatives, there are some 7000 state legislatures, 3000 counties, and 19,000 cities and towns, all with multiple elected offices from mayors, selectboards, and judges to coroners, registers of deeds, mosquito-control boards, and in one Vermont town, dogcatcher. Political scientist Jennifer L. Lawless (2012) puts the number of elected officials at 519,682, although that number substantially undercounts all the other organizations that elect people, from political parties to worker-owned companies and local co-ops.

Who Was and Was Not Allowed to Vote in US History

Although there is no right to vote explicitly set forth in the Constitution, voting is the most commonly recognized form of citizen participation. Yet, since the first colonists arrived in North America, women, people of color, and even groups of men have struggled to gain the right to vote.

Before 1790, mainly only White male property owners 21 years old and older could vote, although free men of color could vote in Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island before 1790, and New Jersey allowed some women to vote until 1807.

Voter participation expanded dramatically in the early 19th century when White men no longer had to hold property in order to vote. To learn more, go to The Expansion of Democracy during the Jacksonian Era.

Voting rights for African American males were established by the 15th Amendment in 1870, which declared that "the right of citizens of the United States to vote cannot be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude" (Voting Rights for African Americans, Library of Congress).

Native Americans gained the right to vote in 1924, although the final state to allow Indians to vote was New Mexico in 1962 (Voting Rights for Native Americans, Library of Congress). The 26th Amendment established the right to vote for 18- to 21-year-olds in 1971.

Voting rights for women were established by the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, but small numbers of women had been voting in some places for a long time. Women voted in New Jersey from 1797 to the early 1800s. They were also granted the right to vote in the territories of Wyoming (1869) and Utah (1870). The history of voting rights for women are explored at Rightfully Hers: Woman Suffrage Before the 19th Amendment from the National Archives.

Minor v. Happersett (1875) Supreme Court Case

During the 1872 Presidential election, Virginia Minor, an officer in the National Women’s Suffrage Association, challenged in court voting restrictions against women.

The first part of Virginia Minor's case was heard in the same courtroom in St. Louis, Missouri where the Dred Scott case was argued in 1847. Minor v. Happersett (1875) eventually went to the Supreme Court, which ruled the Constitution did not grant women the right to vote (Virginia Minor and Women's Right to Vote). Still, Virginia Minor's activism added momentum to the suffrage movement. By the time of the passage of the 19th Amendment, women were already voting in 15 states (Centuries of Citizenship: A Constitutional Timeline).

Learn more at a U.S. Voting Rights Timeline (Northern California Citizenship Project, 2004), a timeline of the History of Voting in America (Office of the Washington Secretary of State), and by visiting the resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki page about Voting Rights in Early 19th Century America.

Voting and the 2016 and 2020 Presidential Elections

Even given the long struggles to expand access to voting, a surprisingly low percentage of people actually participate in national elections. Just 55.7% of the voting-age population cast ballots in the 2016 Presidential Election (Pew Research Center, 2018), while 53% voted in the 2018 midterm elections - the highest number in four decades (United States Census Bureau, April 23, 2019). Turnout is often lower in state, local, or primary elections. Since 1948, Massachusetts has varied between a high of 92% in 1960 (when John F. Kennedy ran for President) to a low of 51% in 2014 (Voter Turnout Statistics, Massachusetts Secretary of State Office, 2020).

The 2020 Presidential election saw 66.5% of the voters casting a ballot, the highest percentage since 1900 (NPR, November 25, 2020). Joe Biden became the first candidate running for President to win more than 80 million votes, the most votes ever cast for a Presidential candidate and 14 million more votes than Hillary Clinton received in 2016. Donald Trump received 11 million more votes than he did in winning the Presidency four years ago.

The Myth of Voter Fraud

Despite repeated claims by the defeated 2020 Presidential candidate Donald Trump and his supporters, voter fraud is "exceedingly rare" in United States elections (Brennan Center for Justice, January 6, 2021). The U.S. Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency declared the 2020 Presidential election the "most secure" in American history, adding there was "no evidence that any voting system deleted or lost votes, changed votes, or was in any way compromised" (Joint Statement, November 12, 2020).

In legal terms, voter fraud is defined as votes cast illegally by an individual by methods such as voting twice, impersonating another voter, or voting when or where one is not registered to vote. There is also a broader category known as election fraud where individuals or organizations seek to interfere with a free and fair election through systematic voter suppression or intimidation, such as buying votes, forging signatures, misinforming voters about polling places and times, deliberately not counting certain votes, or interfering with the collection and counting of mail-in and absentee ballots.

Election fraud also includes violations of campaign finance laws (FindLaw, March 18, 2020). In 2018, Michael Cohen, Donald Trump's former lawyer, pled guilty to multiple counts of tax evasion and campaign finance violations involving unlawful campaign contributions. Donald Trump (known as "Individual 1") was an unindicted co-conspirator in the case (United States Attorney's Office, Southern District of New York, August 21, 2018).

Modules for this Standard

What influences citizens to participate in the political process through voting? The modules for this standard examine this question by first assessing why people do and do not vote before reviewing how secret ballots, poll taxes, literacy tests and modern-day voter suppression laws have impacted people’s voting behaviors and voting rights. A third module asks how the United States might get more people to vote, especially young people.

Information about the processes of elections for Congress and President can be found in Topic 3.4 of this book.

Modules for this Standard Include:

4.5.1 INVESTIGATE: Who Votes and Who Does Not Vote in the United States?

Elections in the United States are decided not only by who votes, but by who does not vote and who is not allowed to vote. FairVote, an election advocacy organization, estimates only about 60% of eligible voters cast a ballot in a presidential election, while as few as 30 to 40% vote in midterm elections. Turnout is generally even lower in local or off-year special elections (Voter Turnout Rates, 1916-2018, FairVote).

In 2016, Donald Trump won the Presidency even though he lost the popular vote to Hillary Clinton by 2,864,974 votes (other candidates received 7,804,213 votes as well). These vote totals mean he was elected President by a little more than a quarter of the eligible voters. View the election results on this interactive map.

In many districts around the country, the number of non-voters actually exceeded the number of people who actually voted. Here is a map of the United States that shows non-voters in the 2016 election.

Voter participation in the United States is lower than in many other countries around the world—Belgium, Sweden and Denmark all have voter turnout rates of 80% or higher. However, Switzerland however consistently has a very low voter turnout—in 2015, less than 39% of the Swiss voting-age population cast ballots for the federal legislature (Pew Research Center, 2018).

Those who vote in this country tend to have more education, higher income, are older in age, and are more likely to be married. Young people, ages 18 to 30, are the least likely group to vote with a rate of 44%. By contrast, 62% of 31- to 60-year-olds and 72% of those 60 and older vote.

Other facts of note include:

- Nearly 30% of the electorate is Black, Hispanic, Asian-American, or some other ethnic minority (quoted from David W. Blight, "On the Election," The New York Review of Books, November 5, 2020, p. 4)

- Individuals with more education are more likely to vote than those with less education.

- Whites are more likely to vote than African Americans, Latinos, and Asians, and citizens of color also lag behind Whites in voter registration rates.

- Nevertheless, Black Voters are credited with helping to deliver three key electoral college states to Joe Biden in the 2020 Presidential elections, accounting for 50% of all Democratic votes in Georgia (16 electoral votes); 20% of Democratic votes in Michigan (16 electoral votes); and 21% of Democratic votes in Pennsylvania (20 electoral votes), effectively making the difference between victory or defeat for Biden in those states (Brookings, November 24, 2020).

Women Voters and the Voting Gender Gap

Today, women are more likely to vote than men, part of a marked voting gender gap. The 1980 Presidential election was a milestone for women voters. It was the first election in which women and men cast the same share of votes. At the same time, only 47% of women voted for Republican winner Ronald Reagan compared to men, 55% of whom supported Reagan. It was the first observable gender gap in Presidential voting, and trend that has continued with women increasingly likely to vote for the Democratic presidential candidate (Women Won the Right to Vote 100 Years Ago. They Didn't Start Voting Differently from Men Until 1980, FiveThirtyEight, August 19, 2020).

Since 1980, women have continued to expand their participation in voting. In every presidential election before 1980, the proportion of men voting exceeded women; in every presidential election since 1980, the proportion of women voting for President has exceeded that of men (Center for American Women and Politics, 2019).

Stated differently, in 2012 and 2016 presidential elections, women outvoted men by 10 million ballots, a number equaling all the votes cast in the state of Texas in 2016. As one commentator noted, "The United States of Women is larger than the United States of Men by a full Lone Star State" (Thompson, 2020, para. 2).

Why People Do Not Vote

Non-voters give different reasons for staying away on election day. According to a 2015 report from the Public Policy Institute of California, the reasons why registered voters do not always vote include:

- Lack of interest (36%)

- Time/schedule constraints (32%)

- Confidence in elections (10%)

- Other (10%)

- Process related (9%)

- Don't know (2%)

Just before the 2020 presidential election, FiveThirtyEight researchers found that non-voters tend to have lower incomes, are young, do not belong to a political party, and are predominantly Asian American or Latino. Among the major reasons given for not voting were missing the registration deadline, not being able to get off work or find where to go to vote, and feeling that the system is broken and their vote will not matter (Why Many Americans Don't Vote, October 28, 2020).

But the FiveThirtyEight pollsters also found other reasons for not voting, besides disinterest or alienation. Many people want vote but cannot. Some reported being unable to access a polling location because of a physical disability. Others said they did not receive an absentee ballot on time, were told their name was not on the registered voter list, did not have an accepted form of identification, or could not receive help filling out a ballot.

Do these reasons apply to people in Massachusetts? What other reasons might people have for not voting?

Suggested Learning Activities

- Investigate online data

- Investigate online data from:

- Interactive maps and cinematic visualizations of how Americans have voted in every election since 1840, Voting America, a website developed by the University of Richmond

- How Many Voted in Your Congressional District in 2018?, United States Census Bureau

- Voter Turnout, MIT Election Data & Science Lab

- What did you uncover about how and why people vote?

- Investigate online data from:

- Civic action project

- Design a proposal, podcast series, social media campaign, or PSA to encourage more people - especially more young people - to vote.

- State your view

- Is voter apathy or lack of voter access the greatest barrier to people voting in this country?

- What evidence can you cite to support your opinion?

- Analyze election results

- Political scientists have identified multiple reasons why people voted for Donald Trump in 2016. What is your view?

- People voted for Trump in response to issues of race and religion. Studies show support for Trump strongly correlated with negative views and overt racial hatred toward Black and Muslim Americans as well as immigrants.

- People voted for Trump in response to issues of economic and technological change. Studies show strong support for Trump in communities hit hard by declines of manufacturing jobs.

- People voted for Trump in response to media coverage of the election.

- People voted for Trump based on religious views. 84% of evangelicals voted for Trump, as did 60% of White Catholics.

- Political scientists have identified multiple reasons why people voted for Donald Trump in 2016. What is your view?

Online Resources for Women's Suffrage, Voting, and Not Voting

- Learn more about the Minor v. Happersett case and women's suffrage using the following resources:

- Virginia Minor and Women's Right to Vote, Gateway Arch, National Park Service

- Newspaper Coverage of Minor v. Happersett, April 3, 1875

- The Legal Case of Minor v. Happersett, from the Women's History Museum

- The Suffragist, Smithsonian lesson plan and media

- Voting resources:

- State-by-State Voter Turnout Maps from FairVote for the 2018, 2016, 2014 and 2012 elections

- Top Ten States with Highest Voter Turnout, ThoughtCo. (March 7, 2019)

- Why Vote? Map-based learning activity from the Boston Public Library

- LEARNING PLAN: The True History of Voting Rights, Teaching Tolerance

Teacher-Designed Learning Plan: Voting from Ancient Athens to Modern America

Voting from Ancient Athens to Modern America is a learning unit developed by Erich Leaper, 7th-grade teacher at Van Sickle Academy, Springfield Massachusetts, during the spring 2020 COVID-19 pandemic when schools went to all remote learning. The unit covers one week of instructional activities and remote learning for students.

It addresses the following Massachusetts Grade 7 and Grade 8 curriculum standards as well as Advanced Placement (AP) Government and Politics unit.

- Massachusetts Grade 7

- Explain the democratic political concepts developed in ancient Greece: a) the "polis" or city state; b) civic participation and voting rights; c) legislative bodies; d) constitution writing; d) rule of law.

- Massachusetts Grade 8

- Describe how a democracy provides opportunities for citizens to participate in the political process through elections, political parties and interest groups.

- Advanced Placement: United States Government and Politics

- Unit 5: Political Participation

- Topic 5.2: Voter Turnout

- Unit 5: Political Participation

This activity can be adapted and used for in-person, fully online, and blended learning formats.

4.5.2 UNCOVER: Voter Suppression and Barriers to Voting

Voter suppression has been defined as "an effort or activity designed to prevent people from voting by making voting impossible, dangerous or just very difficult" (quoted in The True History of Voting Rights, Teaching Tolerance). Voter suppression and barriers to voting can legal and organized, illegal and organized, or illegal and unorganized.

Throughout U.S. history and even while constitutional amendments, court cases, and state and federal laws expanded the right to vote, Poll Taxes, Literacy Tests, and more recently, Voter Restriction Policies, including Voter Identification (ID) laws were used to limit voting by African Americans and other people of color in many states (Berman, 2015).

Carol Anderson has documented this history in her book, One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression is Destroying Our Democracy (2018).

Link here to find out Which states make it hardest to vote?

In this UNCOVER section, we look more closely at how secret ballots, poll taxes, literacy tests, and current day voter restriction laws have made it harder for many people to vote, in the past and today.

Secret Ballots

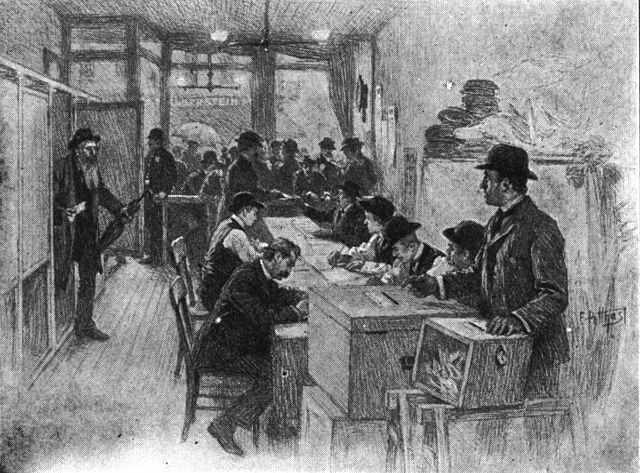

The modern-day image of a solitary citizen going behind a screen or curtain at a voting booth (like the one pictured above) to cast a secret ballot is not the way voting happened for much of United States history (The Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities, 2020).

In the 18th and 19th centuries, noted historian Jill Lepore (2008, 2018), voting was done in public, sometimes by voice, or by a show of hands, or by tossing beans or pebbles into a hat. Paper ballots were only used in some states - Kentucky had voice voting until 1891.

Paper ballots, noted Lepore, were known as "party tickets," printed by political parties (Lepore, 2008, para. 3). Fraud and intimidation were rampant, especially in urban centers where political bosses dominated local politics. According to Lepore, "In San Francisco, party bosses handed out 'quarter eagles,' coins worth $2.50. In Indiana, tens of thousands of men sold their suffrages for no more than a sandwich, a swig, and a fiver" (para. 23).

Reform came with the introduction of the Australian ballot or secret ballot. In 1856, the country of Australia began requiring the government to print ballots and local officials to provide voting booths where individuals could vote in private and in secret. The Australian ballot made its way first to England and then to the United States.

Massachusetts passed the nation's first statewide Australian ballot law in 1888. By 1896, "thirty-nine of forty-five states cast secret, government-printed ballots" (Lepore, 2008, para. 27). At that time, 88% of the nation's voters voted. The numbers of people voting have been declining ever since.

Paradoxically, government printed ballots as part of secret balloting were harder to read "making it more difficult for immigrants, former slaves and the uneducated poor to vote" (Lepore, 2008, para. 25). Many southern states embraced the reform, helping to limit Black men from voting.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Carol Anderson explains the impact of voter suppression on citizens of color.

Poll Taxes

A poll tax is a fee charged to anyone seeking to vote in an election. Poll taxes have been used as a way to keep people who could not afford to pay the tax, particularly African Americans in the South, from participating in local, state and national elections. Poll taxes were outlawed by the 24th Amendment in 1964.

Learn more about poll taxes in United States history:

- White Only: Jim Crow in America discusses ways African Americans were denied the vote

- Edward M. Kennedy Poll Tax Amendment (1965) - Senator Kennedy unsuccessfully sought to extend the 24th Amendment to state and local elections.

Literacy Tests

In political settings, a literacy test is an exam used to assess a potential voter's reading and writing skills as well as civic and historical knowledge. Officials made the questions so difficult that hardly anyone could pass.

Connecticut was the first state to require a literacy test; it was intended to keep Irish immigrants from voting. In the American South, literacy tests were used to prevent African Americans from registering to vote.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 ended the use of literacy tests (Literacy Tests and the Right to Vote).

Modern-Day Voter Restriction Policies

Although restrictions on voting based on race or gender are no longer allowed by law, voter restriction policies are in place in many states that limit people's access to voting.

Widely used voter restriction practices include Voter and Photo Identification (ID) Laws, cutbacks in early voting times and days, and reduced opportunities for people to register to vote.

Proponents claim these laws are needed to prevent voter fraud, although virtually no evidence of such fraud exists (Voter Fraud? Or Voter Suppression?).

For a 2018 example of voter suppression practices, read the following news story: After Stunning Democratic Win, North Dakota Republicans Suppressed the Native American Vote. A federal court found that North Dakota's voter identification laws were disproportionately burdensome to Native Americans.

In the aftermath of the 2020 Presidential election, representatives from both political parties began proposing state-level voting reform legislation, filling hundreds of bills in states throughout the country ("After Record Turnout, GOP Tries to Make It Harder to Vote," Boston Sunday Globe, January 31, 2021). Democrats sought to expand ballot access (such as allowing felons to vote or automatically registering voters at motor vehicle bureaus) while Republicans seek to limit voting (repealing no-excuse absentee ballots or restricting the mailing of absentee ballots to voters).

By May 2021, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, 404 voter restriction bills had been introduced in 48 states. In 11 of those states, including the battleground states of Georgia and Florida, Republican-dominated legislatures had passed a wave of voting laws, putting in place the following policies, many of which impact absentee voting and ballot drop boxes (FiveThirtyEight, May 11, 2021):

- Requiring proof of identity for absentee voting

- Limiting the number of absentee ballots a person can deliver for non-family members

- Requiring signature on absentee ballot match signature on voter registration card (Idaho)

- Limiting absentee ballot requests to one election cycle

- Restricting the locations of ballot drop boxes

- Mandating ballot drop boxes be used only when an election staff member is present

- Eliminating allowing people to register to vote on election day (Montana)

- Banning giving food and water to people waiting in line to vote

Interested in learning more? Check out KQED Learn's "Is Voting Too Hard in the U.S.?" video (below) and discussion activity.

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Video explaining the obstacles to voting faced by many Americans, such as voter ID laws, poll closures, and voter purges.

Suggested Learning Activities

- Take a literacy test

- Can You Pass a Literacy Test? from PBS

- 1965 Alabama Literacy Test

- Consider: Would you be eligible to vote based on your test score?

- Propose a national felony voting policy

- Watch the video: Should People Convicted of a Crime Be Allowed to Vote? from KQED Learn

- In some states, individuals convicted of a crime can vote while in prison; in other states, a felon is barred from ever voting (Felony Voting Rights, National Conference of State Legislatures, October 2020).

- Draft a proposal for a national policy on felony voting

- Resource for additional information: Pros and Cons for Felony Voting

- State your view

- Do you support a Right to Vote Amendment to the Constitution? Why or why not?

- Construct a national voting rights timeline

- Use the following Supreme Court cases to design an interactive multimodal timeline (using Tiki-Toki, Timeline JS, Canva, or another tool) showcasing the history of voting rights:

- Leser v. Garnett (1922) - This decision by the Supreme Court reaffirmed the 19th Amendment that women had the right to vote. Supreme Court Upholds Voting Rights for Women, February 27, 1922

- Guinn v. United States (1915)

- Baker v. Carr (1962)

- Oregon v. Mitchell (1970)

- Crawford v. Marion County Election Board (2008)

- Shelby County v. Holder (2013)

- Evenwel v. Abbott (2016)

- What other cases would you add?

- Use the following Supreme Court cases to design an interactive multimodal timeline (using Tiki-Toki, Timeline JS, Canva, or another tool) showcasing the history of voting rights:

Online Resources for Voting, Poll Taxes, Literacy Tests, and Voter Restriction Laws

- BOOK: Making Young Voters: Converting Civic Attitudes into Civil Action. John B. Holbein & D. Sunshine Hillygus. Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- BOOK: Blackballed: The Black Vote and US Democracy. Darryl Pickney. New York Review Books, 2020.

- Future Voters Project, Teaching Tolerance Magazine

- Expansion of voting and women's suffrage after the Civil War

- Voting Rights and Voter Suppression

- Learning Plans:

- Barriers to Voting, Pennsylvania Bar Association

- Who Gets to Vote?, Washington State Legislature

4.5.3 ENGAGE: Voting by Mail; How Would You Get More People, Especially Young People, to Vote?

Getting more people, especially young people, to vote is a complex public policy and educational problem. There are many proposals and no easy solutions. For an overview, read To Build a Better Ballot: An Interactive Guide to Alternative Voting Systems.

The following section provides an overview of voting reform proposals. What changes are you prepared to support, and why?

Expanded Vote-by-Mail (Vote-at-Home) and Universal Mail-In Voting

Mail-in voting (then called absentee voting) first began during the Civil War when both Union and Confederate soldiers could mail in their votes from battlefields and military encampments. Again, during World War II, soldiers were allowed to vote from where they were stationed overseas. States began allowing absentee voting for civilians who were away from home or seriously ill during the 1880s. California became the first state to permit no-excuse absentee voting (voting by mail for any reason) during the 1980s (Absentee Voting for Any Reason, MIT Election Data Science Lab).

The COVID-19 pandemic renewed calls for the United States to expand vote-by-mail options for American elections. Presently, there are two ways to vote by mail: 1) universal vote-by-mail (also known as vote-at-home), where the state mails ballots to all enrolled voters and 2) absentee balloting, where those who are unable to vote in person on election day must request an absentee ballot and state their reasons for doing so.

In 2016, 33 million people (one-quarter of all votes) voted using one of these procedures. The 2020 election had 60 million people vote by mail, doubling previous totals and accounting for as much as 45% of the total voter turnout (Bazelon, 2020, p. 14, 18).

Five states - Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah and Washington - have universal vote-by-mail in place. In Colorado, which has had its universal vote-by-mail system in place since 2014, fewer than 6 percent vote in person on election day; everyone else votes by mail.

Some states with absentee ballot rules have strict deadlines for getting a ballot and when a deadline is missed, the individual cannot vote.

Voting by mail does not give an advantage to either major political party nor does it increase chances for election fraud (How Does Vote-By-Mail Work and Does It Increase Voter Fraud?, Brookings, June 22, 2020). There is emerging evidence that mail-in voting does increase participation: 1) The vote-at-home states of Colorado, Oregon and Washington were among the top ten in states in voter turnout nationwide; 2) Utah, another vote-at-home state, had the most growth in voter turnout nationally since 2104; 3) Vote at home states outperformed other states by 15.5 percentage points in the 2018 primaries (Nichols, 2018, para. 14). Researchers acknowledge that other factors beside voting by mail might have contributed to increased turnout in those states.

Expanded vote-by-mail proposals include no-excuse absentee voting and extending all-mail elections to every state so everyone receives a ballot in the mail which can be returned by mail or in-person at a voting center (All-Mail Elections: aka Vote-by-Mail, National Conference of State Legislatures).

Read Voting by Mail?, an excerpt from the book Democracy in America? What Has Gone Wrong and What Can We Do About It by political scientists Benjamin I. Page and Martin Gilens (2020).

Compulsory Voting and Universal Civic Duty Voting

In Australia, Argentina, Belgium, Mexico and 18 other countries around the world, it is against the law not to vote. Non-voters face fines and other penalties (22 Countries Where Voting is Compulsory).

Some observers believe that voting should be made compulsory in the United States to get more people involved in the democratic process. Other commentators focus on getting more people registered to vote as a way to increase voter turnout at election time. Presently, in every state except North Dakota, a person must be registered to vote in order to cast a ballot in an election. It is estimated that more than 20% of potentially eligible voters nationally are not registered to vote (Pew Issue Brief, 2017).

Other commentators believe that instilling a ethos that voting is a civic duty is the way to promote greater participation in local, state and national elections. This is known as universal civic duty voting. While advocates of this idea may favor small fines for not voting, they recognize that it is a person's right not to vote if they so choose. The goal is to develop from young ages the disposition that voting is one of the duties or responsibilities that a person has in the democracy. For more, read Lift Every Voice: The Urgency of Universal Civic Study Voting, Brookings (July 20, 2020).

Ranked-Choice Voting or Instant Runoff Voting (IRV)

Ranked-choice or instant runoff voting is being adopted by communities around the country as well as the state of Maine - it is also discussed in Topic 3.4 in this book. The Committee for Ranked Choice Voting explains how it works:

Ranked choice voting gives you the power to rank candidates from your favorite to your least favorite. On Election Night, all the ballots are counted for voters’ first choices. If one candidate receives an outright majority, he or she wins. If no candidate receives a majority, the candidate with the fewest first choices is eliminated and voters who liked that candidate the best have their ballots instantly counted for their second choice. This process repeats and last-place candidates lose until one candidate reaches a majority and wins. Your vote counts for your second choice only if your first choice has been eliminated. (para. 1)

Make Election Day a National Holiday

This idea is simple: make Election Day a national holiday, so people have the time to vote. Numerous countries around the world do so and they generate much higher voter turnout than the U.S. One concern is the loss of revenue for businesses, especially since Juneteenth was just added as a new holiday in 2021. One suggestion countering this problem would be to combine Veterans Day and Election Day in one holiday (Make Election Day a National Holiday, Brookings, June 23, 2021). No new holiday is then added, and voting is further highlighted as everyone's civic duty.

Expanded Early Voting

Early voting means that people can vote on specified days and times before an actual election day, making it possible to fit voting into busy schedules while avoiding long lines and delays at the polls. State laws governing early voting vary across the country; this source includes a state-by-state early voting time chart.

Automatic Voting Registration (AVR)

As of 2020, in 16 states and the District of Columbia, a person is automatically registered to vote when registering for a driver's license (known as Motor Voter Registration) or interacting with some other government agency—unless that person formally opts out. Voter Rolls are Growing Owing to Automatic Voter Registration, NPR (April 11, 2019).

Letting Students Miss School to Vote

Under a law passed in Illinois in 2020 that was initiated by the efforts of high school student activists, students may be excused from classes for up to 2 hours on election day or any day that early voting is offered to vote in general, primary, or special elections. Text of Public Act 101-0624.

Lower the Voting Age to 16 or 17

Lowering the voting age follows from the fact that in most states, 16 year-olds can get married, drive, pay income tax, get a passport, leave school, work full time, and join a union, among other activities (Teenagers are Changing the World. They Should Be Allowed to Vote). In one third of the states, 17-year-olds can register to vote if they turn 18 by election day. There is more information at The Case for Allowing 16-year-olds to Vote.

Same-Day Registration (SDR)

As of May 2021, twenty states and the District of Columbia allow same-day registration (SDR). Under SDR, a person can be automatically registered to vote when they arrive at the polls on election day. In states without SDR, voters must register to vote, often well before Election Day. University of Massachusetts Amherst researcher Jesse Rhodes and colleague Laura Williamson found that SDR boosted Black and Latinx voter turnout between 2 and 17 percentage points as compared to similar states that do not permit same day voter registration.

Additional Proposals

Additional ideas include online voter registration, text alerts reminders to vote, registering young voters at rock concerts and other youth-related events, and extending voting rights for ex-prisoners.

Some observers believe becoming a voter begins at school, as in the following example:

Democracy Prep Public Schools

The founders of the Democracy Prep public school network believe they have a successful model for increasing civic participation, including voting, by students. Democracy Prep serves students in New York City; Camden, New Jersey; Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Las Vegas, Nevada; and San Antonio, Texas. Students are admitted to these schools by randomized lotteries which allow for statistical comparisons between student groups. One study found "Democracy Prep increases the voter registration rates of its students by about 16 percentage points and increases the voting rates of its students by about 12 percentage points" (Gill, et al., 2018, para. 1).

The National Education Policy Center urges caution in interpreting these results. Students chose to apply to Democracy Prep so they may have been inclined toward civic participation before attending. The school had abundant resources from federal grants to develop a strong curriculum.

Still, it is important to ask: How Democracy Prep did promote civic participation and voting among its students? Students were encouraged to "feel an obligation to be true and authentic citizens of a community" (DemocracyPrep, 2020, para. 3). As part of their education, students get to visit with legislators, attend public meetings, testify before legislative bodies, discuss essays on civics and government, participate in "Get Out the Vote" campaigns, and develop a senior-level "Change the World" capstone project.

How many of those actions are happening or could happen at your school?

Media Literacy Connections: Digital Games for Civic Engagement

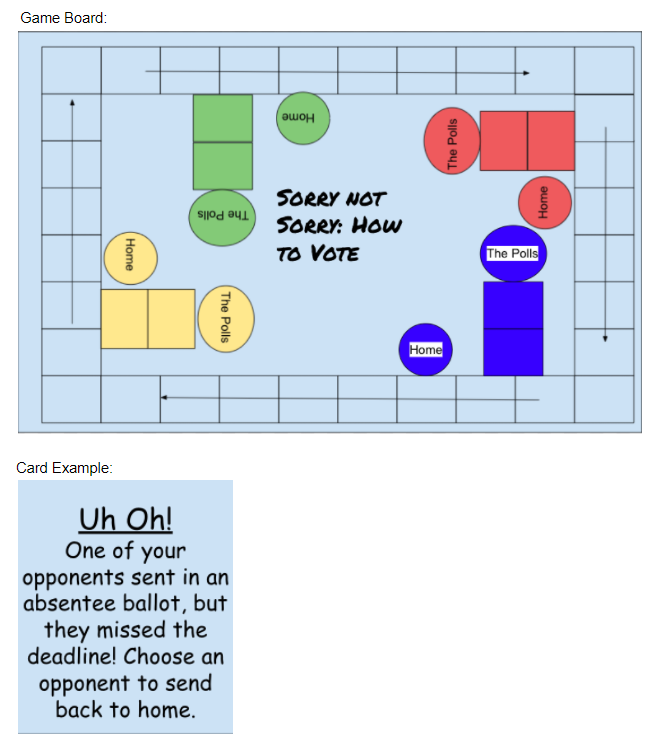

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): Sorry not Sorry: How to Vote by Caroline Gabriel, Ruihan Luo, & Sara Shea

Many educators and game designers believe so and are developing serious games to promote civic awareness and participation. In these activities, you will evaluate a currently available, politically themed online digital games, then design your own game about voting and politics.

Suggested Learning Activities

- Propose a change in your school or classroom

- What changes in school curriculum and activities do you believe would increase civic participation and voting by young people?

- Evaluate voting reform proposals

- Assess and then rank the voting reform proposals in this section according to your first to last priorities, explaining your reasons why.

-

- What other voting reform proposals would you propose?

- Civic Action Project: Design ways to improve voting for people with disabilities

- Listen to the NPR podcast Voters with Disabilities Fight for More Accessible Polling Places

- About 1 in 6 -- more than 35 million -- eligible voters have a disability, a third of whom report difficulties in be able to vote

- Commonly cited barriers include seeing and writing ballots, using voting equipment, traveling to voting locations, getting inside polling places and more.

- Design ways to address these and other potential barriers facing voters with disabilities

- Listen to the NPR podcast Voters with Disabilities Fight for More Accessible Polling Places

Standard 4.5 Conclusion

Voting offers citizens the opportunity to participate directly in democratic decision-making, yet voter turnout in the United States is low with only about 60% of eligible voters casting a ballot in presidential elections, 40% in midterm elections, and often even lower percentages in local elections. INVESTIGATE looked at whether voter apathy or lack of voter access impacts who votes and who does not. UNCOVER examined how poll taxes, literacy tests, and more recently, voter restriction laws, have limited voting by African Americans and members of other diverse groups in American society. ENGAGE asked what steps can be taken to get more people, especially younger people, to vote.