17.5: Discussion

- Page ID

- 77205

Environmental changes can modify health and its determinants in ways that produce security and governance challenges from the local to the global scale. From the standpoint of human security, this chapter has exemplified that security risks related to health have primarily been conceptualized in relation to emergent biological threats, but that a conceptualization of social-ecological systems encourages us to consider dimensions of time and space in manifesting systems vulnerabilities and its ability to adapt to change.

Environmental change will exacerbate existing inequities, and will also produce emergent implications for human health and the public and acute care response system to identify threats that may not be immediate, but long term and unfolding over broad geographic areas rather than resulting from a single point of origin. The time and space considerations here are significant, given that environmental change will continue to unfold in perpetuity, affecting different bioregions of the planet and the populations that reside there in nuanced and highly contextual ways. Moreover, it raises significant questions about how to promote environmental health in ways that are just and fair, thereby requiring an ethical analysis of the equity impacts of change across different scales (i.e. local, regional, national, international, planetary), but also the governance responses to promoting sustainability and mitigating or adapting to associated health impacts (Buse, Smith, et al., 2018). If normative dimensions of the health security discourse remain focused on the emergence and treatment of direct, biophysical risks to human populations, we risk limiting our response to much larger, slower-moving emergencies that will undoubtedly affect all life on the planet.

Towards Integrative Approaches to Health Security and Social-ecological Change

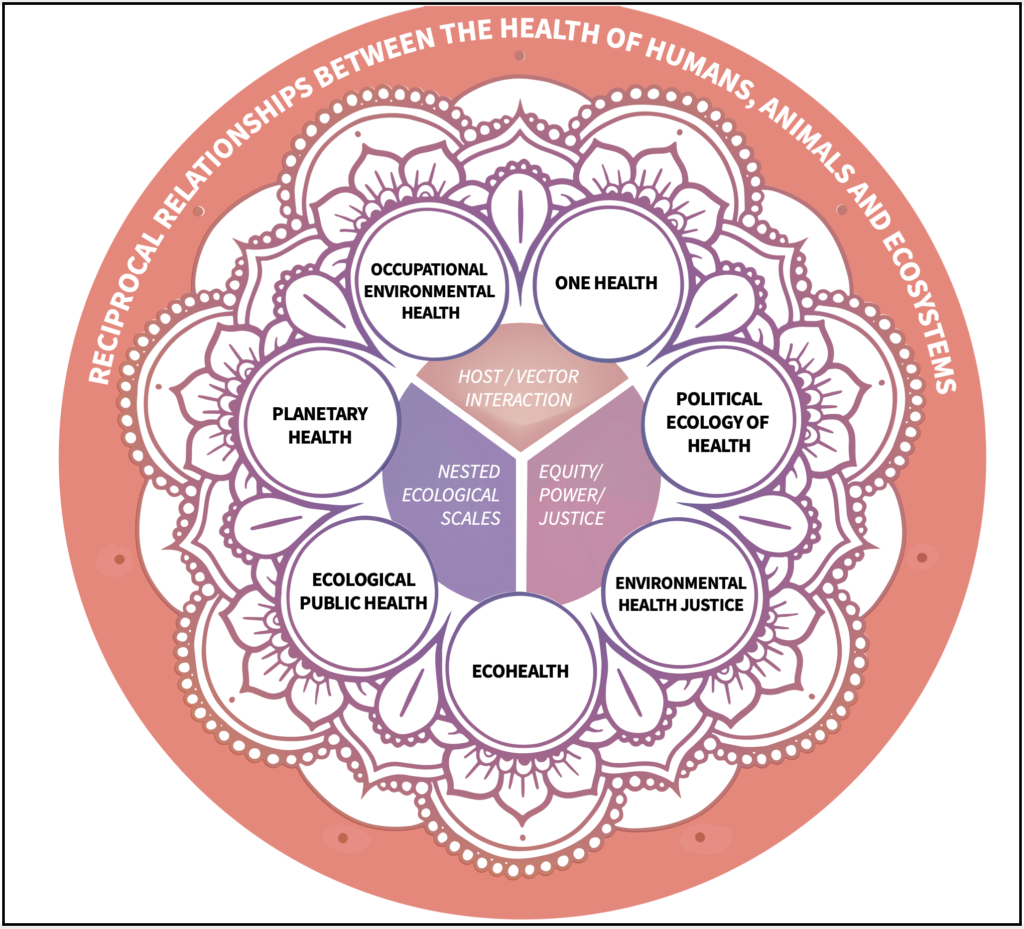

Fortunately, scholarship linking environmental and ecological contexts to the health of human and non-human entities has grown considerably over the past 150 years (Buse, Oestreicher, et al., 2018). For example, Buse, Oestreicher, et al. (2018) outline the emergence of seven ‘fields’ of environmental public health practice that simultaneously seek to address the disease/host interface present across much of the health security discourse, but to consider those interactions across nested ecological scales in ways that are attentive to equity and justice (see Figure 17.3). These fields are further built upon by Oestreicher et al. (2018) to conceptualize a variety of scholarly and applied disciplines actively working to understand and respond to the health risks posed by environmental change.

Human and health security has not necessarily been at the fore of any one of these field developments, but is implicit to their study. In the above section on health security, we see that it is often framed in response to an emerging threat (e.g. climate refugees and mass migrations, exposure to pandemic influenza) that rely on the interaction between a broader physical context and the human body. However, understanding how fields and systems are nested within one another encourages the consideration of the determinants of health, and how health promoting and protecting resources may unfairly benefit some segments of society relative to others. In other words, each of these fields, by virtue of their engagement with health and its determinants, implicitly understands that the health and security of a population is a fundamental and orienting goal of many public health responses to various crises.

Recommendations for Future Research, Education and Practice

What is clear from the analysis above is the emergence of several trajectories and priorities for research and capacity-strengthening to support policies and practices that can promote health security in a time of profound environmental change. First, there is an analytic requirement for health security to more fulsomely engage with existing definitions of health security in ways that account for its social, political, economic and environmental determinants. Conventional definitions overly privilege direct, biophysical risks to human health, perhaps risking considerations of the emergent, distal, and indirect risks to health and well-being posed by unique interactions among specific places and determinants of health. Broadening the health security definition is particularly helpful in recognizing environmental change as a considerable threat to health security in the 21st century. Not only will humanity continue to struggle to adapt to the impacts of climate change and a host of other bio-geo-chemical change processes that threaten our very existence if left unaddressed, but such a definition would necessarily broaden the spatial and temporal purview of health security. Indeed, many of the ecological threats to human health discussed in this chapter are playing out on timescales that not only create direct and immediate health risks, but they will continue to do so, changing and evolving in form and severity, over the course of generations. Recognizing slow moving emergencies as inherent risks to health security that unfold over diverse parts of the planet is essential given the spatial and equity dynamics at play.

Second, concerted research attention needs to be directed towards the equity dimensions of health security responses to the health impacts of environmental change, but also conventional biosecurity threats such as weapons of mass destruction and biological agents. Many of the health security threats unfolding around the world disproportionately affect low and middle-income countries due to significant capacity and infrastructure challenges, despite much of the world’s pollution and ecological threshold exceedances being driven by high-income countries’ past rapid industrial growth, and middle-income countries’ current growth. The health equity impacts of environmental change are well-studied, but further policy guidance on promoting equitable responses to health security issues, including weighing multiple trade-offs across multiple emergencies operating at different regional and temporal scales, is desperately needed. Research that seeks to unpack the equity dimensions of a just and equitable response to the health security implications of global environmental change must ask important questions about the distribution of resources and populations serviced by interventions. This is of particular relevance in contexts defined by colonial histories of physical and cultural violence, particularly against Indigenous populations, or where pre-existing population groups are differentially exposed to an environmental harm through unjust land-use or zoning policies. Ensuring a fair and equitable process is therefore central to the pursuit of environmental health justice, and is a rich area for future research on health security.

Third, there is considerable need for capacity-strengthening efforts that promote integrative understandings of health, human security and the drivers and impacts of environmental change. The discussion throughout this chapter has demonstrated the myriad ways in which health outcomes manifest from ecological change processes, but also the ways in which they produce security threats for individuals, regions, nation states and the broader international community. In embracing a definition of health security that includes the determinants of health, we draw attention to the integrative imperatives that cross-cut spatial, temporal, sectoral, value-based and disciplinary responses to security threats (see Table 17.1).