2.2: Four Approaches to Research

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 135831

- Dino Bozonelos, Julia Wendt, Charlotte Lee, Jessica Scarffe, Masahiro Omae, Josh Franco, Byran Martin, & Stefan Veldhuis

- Victor Valley College, Berkeley City College, Allan Hancock College, San Diego City College, Cuyamaca College, Houston Community College, and Long Beach City College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify, and distinguish between, the four different approaches to research.

- Consider the advantages and disadvantages of each research approach.

- Compare and contrast the four approaches to research.

- Identify best practices for when and how to use case studies.

Introduction

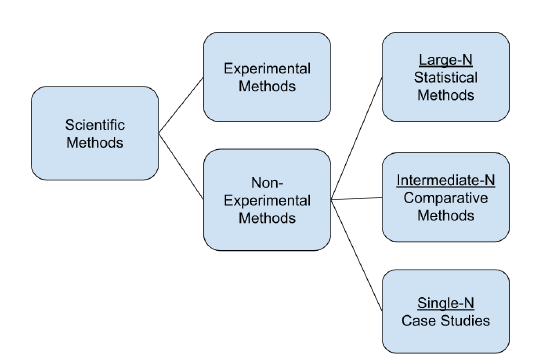

In empirical research, there are four basic approaches: the experimental method, the statistical method, case study methods, and the comparative method. Each one of these methods involves research questions, use of theories to inform our understanding of the research problem, hypothesis testing and/or hypothesis generation. Each method is an attempt to understand the relationship between two or more variables, whether that relation is correlational or causal, both of which will be discussed below.

The Experimental Method

What is an Experiment? An experiment is defined by McDermott (2002) as “laboratory studies in which investigators retain control over the recruitment, assignment to random conditions, treatment, and measurement of subjects” (pg. 32). Experimental methods are then the aspects of experimental designs. These methodological aspects involve “standardization, randomization, between-subjects versus within-subject design, and experimental bias” (McDermott, 2002, pg, 33). The experimental method assists in reducing bias in research, and for some scholars holds great promise for research in political science (Druckman, et. al. 2011). Experimental methods in political science almost always involve statistical tools to discern causality, which will be discussed in the next paragraph.

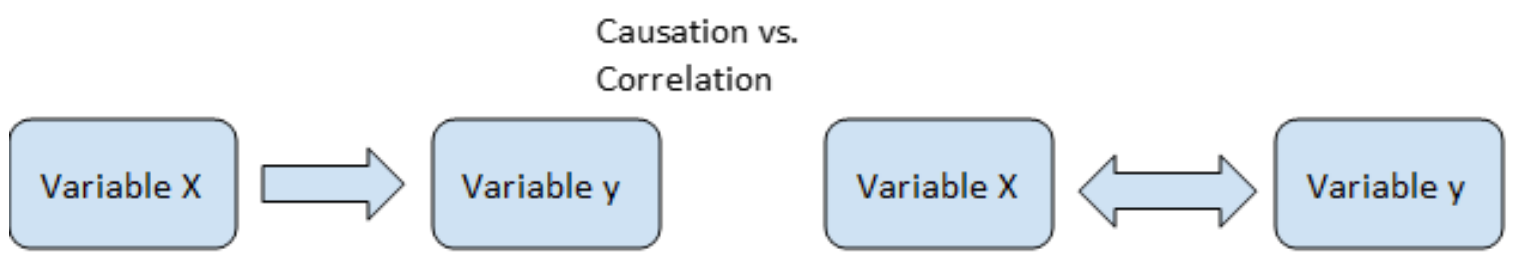

An experiment is used whenever the researcher seeks to answer causal questions or is looking for causal inference. A causal question involves discerning cause and effect, also referred to as a causal relationship. This is when a change in one variable verifiably causes an effect or change in another variable. This differs from a correlation, or when only a relationship or association can be established between two or more variables. Correlation does not equal causation! This is an often repeated motto in political science. Just because two variables, measures, constructs, actions, etc. are related, does not mean that one caused the other. Indeed, in some cases, the correlation may be spurious, or a false relationship. This can often occur in analyses, especially if particular variables are omitted or constructed improperly.

A good example involves capitalism and democracy. Political scientists assert that capitalism and democracy are correlated. That when we see capitalism, we see democracy, and vice versa. Notice, that nothing is said about which variable causes the other. It may well be that capitalism causes democracy. Or, it could be that democracy causes capitalism. So X could cause Y or Y could cause X. In addition, X and Y could cause each other, that is capitalism and democracy cause each other. Similarly, there could be an additional variable Z that could cause both X and Y. For example, it may not be that capitalism causes democracy or that democracy causes capitalism, but instead something completely unrelated, such as the absence of war. The stability that comes from an absence of war could be what allows both capitalism and democracy to flourish. Finally, there could be a(n) intervening variable(s), between X and Z. It is not capitalism per se that leads to democracy, or vice-versa, but the accumulation of wealth, often referred to as the middle class hypothesis. In this case, it would be X→A→Y. Using our example, capitalism produces wealth, which then leads to democracy.

Real world examples of the discussion above exist. Most wealthy countries are democratic. Examples include the United States and most of western Europe. However, this is not the case for all. The oil producing countries in the Persian Gulf are considered wealthy, but not democratic. Indeed, the wealth produced in natural resource rich countries may reinforce the lack of democracy as it mostly benefits the ruling classes. Also, there are countries, such as India, which are strong democracies, but are considered developing, or poorer nations. Finally, some authoritarian countries adopted capitalism and eventually became democratic, which would seem to confirm that middle class hypothesis discussed above. Examples include South Korea and Chile. However, we see plenty of other countries, such as Singapore, that are considered quite capitalistic have developed a strong middle class, but have yet to fully adopt democracy.

These potential contradictions are why we are careful in political science with making causal statements. Causality is difficult to establish, especially when the unit of analysis involves countries, which is often the case in comparative politics. Causality is a bit easier to establish when experimentation involves individuals. The inclusion of a treatment variable, or the manipulation of just one variable across a number of cases, can suggest causality. The reiteration of an experiment multiple times can confirm this. A good example includes interviewer effects among respondents in surveys. Experiments consistently show that the race, gender, and/or age of the interviewer can affect how an interviewee responds to a question. This is especially true if the interviewer is a person of color and the interviewee is white and the question that is asked is about race or race relations. In this case, we can make a strong argument that interviewer effects are causal. That X causes some kind of effect in Y.

Given this, are there any causal statements made by comparativists? The answer is a qualified yes. Often, the desire for causality is why comparative political scientists study a small number of cases or countries. One case/country, or small number of cases/countries, analyses lend itself well to searching for a causal mechanism, which will be discussed in further detail in Section 2.4 below. Are there any causal statements in comparative politics that involve lots of cases/countries? The answer is again a qualified yes. Democratic peace theory is explained in Section 4.2 of this textbook:

“Democracies per se do not go to war with each other because they have too much in common - they have too many shared organizational, political and socio-economic values to be willing to fight each other - therefore, the more democratic nations there are the more peaceful the world will become and remain.”

This is as close as it comes to empirical law in comparative politics. Yet even in democratic peace theory there are ‘exceptions’. Some cite the U.S. Civil War as a war between two democracies. However, an argument can be made that the Confederacy was a flawed or unconsolidated democracy and ultimately not a war between two real democracies. Others point to U.S. interventions in various countries during the Cold War. These countries, Iran, Guatemala, Indonesia, British Guyana, Brazil, Chile, and Nicaragua, were all democracies. Yet, even these interventions are not convincing to some scholars as they were covert missions in countries that were not quite democratic (Rosato, 2003).

Statistical Methods

What are Statistical Methods? Statistical methods are the use of mathematical techniques to analyze collected data, usually in numerical form, such as interval or ratio-scale. In political science, statistical analyses of datasets are the preferred method. This mostly developed from the behavioral wave in political science where scholars became more focused on how individuals make political decisions, such as voting in a given election, or how they may express themselves ideologically. This often involves the use of surveys to collect evidence regarding human behavior. Potential respondents are sampled through the use of a questionnaire constructed to elicit information regarding a particular subject. For example, we may develop a survey that asks Americans regarding their intention on taking one of the approved COVID-19 vaccines, if they intend to get a booster in the future, and their thoughts on pandemic-related restrictions. Respondent choices are then coded, usually using a scale of measurement, and the data is then analyzed often with the use of a statistical software program. Researchers may also rely on the existing data from various sources (e.g., government agencies, think tanks, and other researchers) to conduct their statistical analyses. Scholars probe for correlations among the constructed variables for evidence in support of their hypotheses on the topic (Omae & Bozonelos, 2020).

Statistical methods are great for discerning correlations, or relationships between variables. Advanced mathematical techniques have been developed that permit understanding of complex relationships. Given that causation is difficult to prove in political science, many researchers default to the use of statistical analyses to understand how well certain things relate. This is particularly true when it comes to applied research. Applied research is defined as “research that attempts to explain social phenomena with immediate public policy implications'' (Knoke, et. al. 2002, pg. 7). Statistical methods are also the preferred approach when it comes to the analysis of survey data. Survey research involves the examination of a sample derived from a larger population. If the sample is representative of the population, then the findings of the sample will allow for the formation of inferences about some aspect of the population (Babbie, 1998).

At this point, we should review the discussion regarding one of the major partitions in political science, as noted in Chapter One, quantitative methods involve a type of research approach which centers on testing a theory or hypothesis, usually through mathematical and statistical means, using data from a large sample size. Qualitative methods are a type of research approach which centers on exploring ideas and phenomena, potentially with the goal of consolidating information or developing evidence to form a theory or hypothesis to test. Quantitative researchers collect data on known behavior or actions, or close-ended research where we already know what to look for, and then make mathematical statements about them. Qualitative researchers collect data on unknown actions, or open-ended research where we do not already know what to look for, and then make verbal statements about them. This divide has subsided somewhat, with concerted efforts to develop mixed methods research designs, however, researchers often segregate themselves into one of these two camps.

When looking at the three basic approaches, the first two methods - experimental and statistical - fall squarely into the quantitative camp, whereas comparative politics is mostly considered as qualitative. Experimental and statistical methods have their roots in the behavioral revolution of the 1950s, which shifted the focus of the inquiry from institutions to the individual. For example, the fields of behavioral economics and social psychology are well suited for experiments. Both studies focus on the behavior of individual people. For example, behavioral economists are interested in human judgment when it comes to financial and economic decisions. Social psychologists have been traditionally more interested in learning behavior and information processing. As political science has shifted more towards the study of individual political behavior, experimentation and statistical analysis of collected data, through experiments, surveys and other methods.

For more on the history of this divide and how it has affected political science, see Franco and Bozonelos’s (2020) chapter on the History and Development of the Empirical Study of Politics in Introduction to Political Science Research Methods.

The Comparative Method

What is the Comparative Method? The comparative method is often considered one of the oldest approaches in the study of politics. Ancient Greek philosophers, such as Plato, the author of The Republic, Aristotle, the author of Politics, and Thucydides, the author of the History of the Peloponnesian War wrote about politics in their times in a comparative manner. Indeed, as Laswell (1968) said, all science is 'unavoidably comparative'. Most scientific experiments or statistical analyses will have a control or reference group. The reason is so that we can compare the results of our current experiment and/or analysis to some baseline group. This is how knowledge develops; by grafting new insights through comparison.

Likewise, comparison is more than just description. We are not only analyzing the differences and/or similarities, we are conceptualizing. We cannot overstate the importance of concepts in political science. A concept is defined as “an abstract or generic idea generalized from particular instances” (Merriam-Webster). For political scientists, concepts are “generally seen as nonmathematical and deal with substantive issues” (Goertz, 2006). For example, if we want to compare democracies, we must first define what exactly constitutes a democracy.

Even in quantitative analyses, concepts are always understood in verbal terms. Given that there are quite a few ways to formulate quantitative measurements, conceptualization is key. Developing the right scales, indicators, or reliability measures is predicated on having one’s concepts right. A good example is the simple, yet complicated concept of democracy. Again, what exactly constitutes a democracy? We are sure that it must include elections, but not all elections are the same. An election in the U.S. is not the same as an election in North Korea. Clearly, if we want to determine how democratic a country is, and develop good indicators from which to measure, then concepts matter.

Comparative methods occupy an interesting space in methodology. Comparative methods involve “the analysis of a small number of cases, entailing at least two observations”. Yet it also involves “too few [cases] to permit the application of conventional statistical analysis” (Lijphart, 1971; Collier, 1993, pg 106). This means that the comparative method involves more than a case study, or single-N research (discussed in detail below), but less than a statistical analysis, or large-N study. It is for this reason that comparative politics is so closely intertwined with the comparative method. As we tend to compare countries in comparative politics, the numbers end up somewhere in between, anywhere from a few to sometimes over fifty. Cross-case analysis through the comparison of key characteristics, are the preferred methods in comparative politics scholarship.

Case Studies

Why would we want to use a case study? Case studies are one of major techniques used by comparativists to study phenomena. Cases provide for the in-depth traditional research. Many times there is a gap in knowledge, or a research question that necessitates a certain level of detail. Naumes and Naumes (2015) write that the case studies involve storytelling, and that there is power in the story’s message. Clearly, these are stories that are based in fact, rather than in fiction, but nevertheless, are important as they describe situations, characters, and the mechanisms for why things happen. For example, the exact cause of how the SARS-CoV-2 virus, more commonly referred to as COVID-19, will involve telling that story.

A case is defined as a “spatially delimited phenomenon (a unit) observed at a single point in time, or over some period of time” (Gerring, 2007). Others define a case as “factual description of events that happened at some point in the past” (Naumes and Naumes, 2015). Therefore, a case can be broadly defined. A case could be a person, a family household, a group or community, or an institution, such as a hospital. The key question in any research study is to clarify the cases that belong and the cases that do not belong (Flick, 2009). If we are researching COVID-19, at what level should we research? This is referred to as case selection, which we discuss in detail in Section 2.4.

For many comparativists in political science, the unit (case) that is often observed is a country, or a nation-state. A case study then is an intensive look into that single case, often with the intent that this single case may help us better understand a particular variable of interest. For example, we could research a country that experienced lower levels of COVID-19 infections. This case study could consist of a single observation within the country, with each observation having several dimensions. For example, if we want to observe the country’s successful COVID-19 response, that observation could include the country’s level of health readiness, their government’s response, and the buy-in from their citizens. Each of these could be considered a dimension of the single observation - the successful response.

This description listed above is considered the traditional understanding of case study research - the in-depth analysis of one case, in our example of that one country, to find out how a particular phenomenon took place, a successful COVID-19 response. Once we research and discover the internal processes that led to the successful response, we naturally want to compare it to other countries (cases). When this happens, shifting the analysis from just one country (case) to other countries (cases), we refer to this as a comparative case study. A comparative case study is defined as a study that is structured on the comparison of two or more cases. Again, for comparative political scientists, we often compare countries and/or their actions.

Finally, as mentioned in Chapter One, there can also exist subnational case study research. This is when subnational governments, such provincial governments, regional governments, and other local governments often referred to as municipalities, are the cases that are compared. This can happen entirely within a country (case), such as comparing COVID-19 response rates among states in Mexico. Or it can happen between countries, where subnational governments are compared. This often occurs in studies of European and/or European Union policy. There are quite a few subnational governments with significant amounts of political power. Examples include fully autonomous regions, such as Catalonia in Spain, partially autonomous regions, such as Flanders and Walloons in Belgium, and regions where power was devolved, such as Scotland within the UK.

Use of Case Studies in Comparative Politics

As mentioned above, case studies are an important part of comparative politics, but they are not exclusive to political science. Case studies are used extensively in business studies for example. Ellet (2018) notes that case studies are “an analogue of reality”. They help readers understand particular business decision scenarios, or evaluation scenarios where some process, product, service, or policy is being evaluated on their performance. Business case studies also feature problem diagnosis scenarios, where the authors research when a business is not successful, and try to understand the actions, processes, or activities that led to failure. Case studies are also relevant in medical studies as well. Clinical case studies investigate how a diagnosis was made. Solomon (2006) notes that many of the case studies published by physicians are anecdotal reports, where they notate their procedures for diagnosis. These case studies are vitally important for the field of medicine as they allow researchers to form hypotheses on particular medical disorders and diseases.

Case studies are vital to theory development in political science. They are the cornerstones of different discourses in the discipline. Blatter and Haverland (2012) note that a number of case studies have reached ‘classic’ status in political science. These include Robert Dahl’s Who Governs? [1961], Graham T. Allison’s Essence of Decision [1971], Theda Skocpol’s States and Social Revolutions [1979], and Arend Ljiphart’s The Politics of Accommodation [1968]. Each of the classics is a seminal study into an important aspect in political science. Dahl’s work popularized the concept of pluralism, where different actors hold power. Allison studied the decision-making processes during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, whose work was influential for public policy analysis. Skocpol’s book laid out the conditions from which a revolution may take place. Skocpol’s work coincided with the rise of neo-institutionalism in the 1970s, where political scientists began to refocus their attention on the role of institutions in explaining political phenomena. Finally, Ljiphart gave us the concepts of “politics of accommodation” and “consensus democracy”. The terms are central to our understanding of comparative democracy.

As mentioned earlier, cases in comparative politics have historically focused on the nation-state. By this we mean that researchers compare countries. Comparisons often involve regime types, including both democratic and nondemocratic, political economies, political identities, social movements and political violence. All of these comparisons require scholars to look within countries and then compare. As stated in Chapter One, this “looking within” is what separates comparative politics from other fields of political science. Thus, as the nation-state is the most relevant and important political actor, this is where the emphasis tends to be.

Clearly, the nation-state is not the only actor in politics. Nor is the nation-state, the only level of analysis. Other actors exist in politics, from subnational actors, ranging from regional governments to labor unions, and all the way to insurgents and guerillas. There also exist transnational actors, such as nongovernmental organizations, multinational corporations, and also more sinister groups such as criminal and terrorist networks. In addition, we can analyze at different levels, including the international (systemic) level, the subnational level, and at the individual level. However, nation-states remain the primary unit and level of analysis in comparative politics.