2.1: The Scientific Method and Comparative Politics

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 135830

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Consider the factors which make political science, and thereby comparative politics, a science.

- Identify and be able to describe the steps and key terms used in the scientific method.

Introduction

When many people consider the field of science, they may think of laboratories filled with clinicians in white lab coats, chemical experiments with bubbling vials, or vast chalkboards of mathematical equations. Many times, the word ‘science’ will conjure images of what are called the hard sciences. Hard sciences, such as chemistry, mathematics, and physics, work to advance scientific understanding in the natural or physical sciences. In contrast, soft sciences, like psychology, sociology, anthropology and political science, work to advance scientific understanding of human behavior, institutions, society, government, decision making, and power. Based on their interests and scope of inquiry, the soft sciences are interested in the social sciences, which are the fields of inquiry that scientifically study human society and relationships. Both hard and soft sciences provide significant contributions to the world of scientific inquiry, though soft sciences are often misunderstood and underappreciated for their contributions, largely based on lack of understanding of how these sciences engage the scientific method. In considering the different challenges facing hard and soft sciences, Physicist Heinz Pagels called the social sciences the “sciences of complexity,” and said further, “the nations and people who master the new sciences of complexity will become the economic, cultural, and political superpowers of the 21st century" (Pagels, 1988). To this end, the advancements made by the soft sciences, like political science, should not be undercut or diminished, but sought to be understood and further pursued. Indeed, as science is defined as the systematic and organized approach to any area of inquiry, and utilizes scientific methods to acquire and build a body of knowledge, political science, as well as comparative politics as a subfield of political science, embody the essence of the scientific method and possess deep foundations for the scientific tools and theory formation which align with their areas of inquiry.

Recall from Chapter One, “Comparative politics is a subfield of study within political science that seeks to advance understanding of political structures from around the world in an organized, methodological, and clear way”. The scholars of comparative politics are interested in understanding how particular incentives, patterns and institutions may prompt people to behave in certain ways. This understanding takes place in countries that are both similar in their outlook, but also different as well (Later, in relation to case selection, we will broach Mill’s approaches of Most Similar Systems Approach, and Most Different Systems Approach). In observing countries and their similarities and differences, we need to be able to distinguish between actions or decisions that are happening systematically from actions or decisions that may happen randomly. To this end, political scientists follow and rely on the rules of scientific inquiry to conduct their research. In the sections below, we introduce characteristics which affirm political science as a science, followed by the principles of scientific methods and the process of scientific inquiry as it is applicable to comparative politics.

Why is Political Science a Science?

The nature of human behavior within political relationships has been studied and considered for centuries, but has not always operated under a strictly scientific scope. Thucydides, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle all provided observations on their political worlds and ideas about why states and political actors may behave the way they do. The contributions of many famous philosophers and political thinkers over time has lent greatly to the field of politics, but the modern conception of Political Science is one that, like other social sciences, follows the scientific method and is based on a large depth of philosophy tradition regarding the nature of inquiry. Beginning in the late 1800s, scholars began attempting to treat political science, and indeed most of the social sciences, as a hard science that could utilize the scientific method. Through decades of debate, some level of consensus was met through scholastic political science communities as to defining the characteristics of research in political science and how research could best be conducted.

A seminal work in the field of Political Science that sought to describe the features of scientific research within the field came from Gary King, Robert Keohane and Sidney Verba, who wrote, Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research in 1994. Although the book was discussing political science in relation to qualitative research methods, which will be discussed later in this chapter, they also spent a generous amount of time considering what scientific research in political science looks like.

According to King, Keohane, and Verba (1994), scientific research has four main characteristics. First, one of the primary purposes of scientific research is to make descriptive or causal inferences. An inference is a process of drawing a conclusion about an unobserved phenomenon, based on observed (empirical) information. It is important to note that accumulation of facts, by itself, does not make such an effort scientific. This is true no matter how systematically one is collecting the facts or the types of information being collected. In order for a study to be scientific, it requires the additional step of going beyond the immediately observable information in an effort to learn about something broader that is not directly observable. The process of making inferences can help us learn about the unobserved facts by describing it based on empirical information. For example, while we cannot directly observe democracy, political scientists have identified various tenets and characteristics of democratic nations, to the extent where we can describe such a concept. We can also learn the causal effects from the observed information. For example, political scientists have been studying and attempting to identify the cause of war and the process of a successful war termination.

Second, the procedures of scientific research must be public. Scientific research relies on 'explicit, codified, and public methods' so that the reliability of a study can be assessed effectively. It is critical that the process of gathering and analyzing information/data are reliable for the above described process of making inferences. As a condition for publication, it is often required for the authors of a published work to share data files or survey questionnaires to ensure that anyone could possibly replicate the work to assess its reliability as well as to evaluate the appropriateness of the method being used in such work.

Third, because of the fact that the process of making inferences is imperfect, the conclusions of scientific research are uncertain as well. Researchers must be aware of a reasonable estimate of uncertainty in their work to ensure that they can effectively interpret their conclusions. By definition, inferences without some level of uncertainty are not scientific. This idea relates to one of the most critical characteristics of a good theory, that is a theory must be falsifiable (discussed more in the sections below).

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the content of scientific research is the method. It means that whether one’s research is scientific or not is determined by the way it is conducted as opposed to the subject matter of what is being studied. Scientific research must adhere to a set of rules of inference because its validity is dependent on how closely one follows such rules and procedures. Simply put, one can virtually study anything in a scientific manner as long as the researcher follows the rules of inference and scientific methods.

The Scientific Method

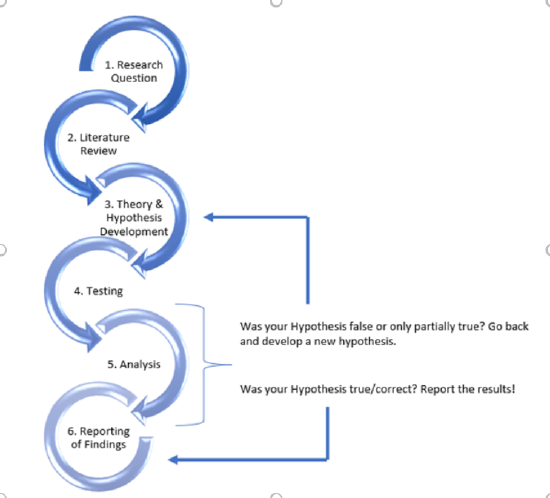

If you have ever enrolled in a science course, you have likely encountered the scientific method. The scientific method is a process by which knowledge is acquired through a sequence of steps, which generally include the following components: question, observation, hypothesis, testing of the hypothesis, analysis of the outcomes, and reporting of the findings. Ideally, use of the scientific method will build a body of knowledge and culminate in the formation of inferences and potentially theories for why/how phenomena exist or occur. It is useful to briefly consider each of these components in deconstructing how political scientists approach their areas of interest.

Broadly speaking the scientific method within political science will involve the following steps (each of these steps will be explored in-depth in this section):

- The research question: Develop a clear, focused and relevant research question. Although this sounds like a simple step, the following section will lay out, in detail, the complexity of forming a sound research question.

- Literature review: Research the context and background information and previous research regarding this research question. This part becomes the political scientist’s literature review. A literature review becomes a section of your research paper or research process which collects key sources and previous research on your research question and discusses the findings in synthesis with each other. From this work, you are able to have a full scope of understanding of all previous work performed on your topic, which will enhance knowledge in the field.

- Theory and hypothesis development: Develop a theory that explains a potential answer to your research question. A theory is a statement that explains how the world works based on experience and observation. From the theory, you will construct hypotheses to test the theory. A hypothesis is a specific and testable prediction of what you think will happen; a hypothesis, or set of hypotheses, will describe, in very clear terms, what you expect will happen given the circumstances. Within the hypothesis, variables will be identified. A variable is a factor or object that can vary or change. As political scientists are concerned with cause-and-effect relationships, they will divide the variables into two categories: independent variables (explanatory variables) are the cause, and these variables are independent of other variables under consideration in a study. Dependent variables (outcome variables) are the assumed effect, their values will (presumably) depend on the changes in the independent variables.

- Testing: A political scientist, at this stage, will test the hypothesis, or hypotheses, through observation of the relationship between the designated variables.

- Analysis: When the testing is complete, political scientists will need to review their results and draw conclusions about the findings. Was the hypothesis correct? If so, they will be able to report the success of their findings. Was the hypothesis incorrect? That’s okay! A famous quip in this field is, 'no finding is still a finding.' If the hypothesis was not proven true, or fully true, then it is back to the drawing board to rethink a new hypothesis and do the testing again.

- Reporting of findings: Reporting results, whether the hypothesis is true, partially true, or outright false, is critical to the advancement of the overall field. Typically, researchers will attempt to publish their findings so the findings are public and transparent, and so others may continue research in that area.

Step One: The Research Question

Most research, of any kind, begins with a question. Indeed, before a researcher can start thinking about describing or explaining a phenomenon, one must start with refining the question about one’s phenomenon of interest. After all, political science research is about solving an unsolved puzzle, so we must identify a question to be answered through rigorous research. So how do you determine what characteristics define a good political research question?

First, a substantive and quality political science question needs to be relevant to the real political world. It does not mean that the research questions must only address current political affairs. In fact, many political scientists study historical events and past political behaviors. However, the results of political science research are often relevant to the current political environment and may come with policy implications. A political research question that is highly hypothetical may be interesting and important on its own. Second, as an academic discipline, political science research is a means through which the discipline grows in terms of its knowledge about the political realm. As such, good political science research needs to contribute to the field. Overall, a political science research question must be a question, and this is an important point. A question in this context must be something that the answer to such a statement has a chance of being wrong. In other words, a research question has to be falsifiable. Falsifiability is a word coined by Karl Popper, a philosopher of science, and is defined as the ability for a statement to be logically contradicted through empirical testing. (Empirical analysis is defined as being based on experiment, experience or observation).

Importantly, some questions are inherently non-falsifiable, meaning the question cannot be proven true or false under present circumstances, particularly questions which are subjective (e.g. Are oranges better than lemons?) or technical limitations (Do angry ninja-robots live in Alpha Centauri?). Consider the subjective example in political science, a question like: Which one is better, North Dakota or South Dakota? This question is subjective and may ultimately, if not further described or delineated, result in nothing more than a matter of one’s taste. If the question was more refined and not simply a case of some abstract definition of ‘better than,’ perhaps the researcher is actually trying to ask something that can be proven: Which state is more economically productive, North or South Dakota? From here, the researcher could lay out metrics for what constitutes economically productive, and try to build from there. Consider now a technical limitations problem in political science, for instance, what if someone tried to ask: Does investing in a country’s education system always mean they will eventually become democratic? There’s two problems with this question. First, making a blanket statement that investing in education always leads to democracy can lend itself to problems. Will you be able to test every situation and circumstance where education systems are invested in and democracy happens? Second, there’s an issue with the word ‘eventually.’ A country that invests heavily in education could become democratic 700 years from now. If the time span ends up being 700 years, we cannot truly infer that it was the initial investment in education that was the cause of that county’s democratic transition.

Step Two: The Literature Review

Once you’ve found the research question, it’s important to consider how much you actually know about the topic, and to do a search about any relevant previous research that has ever been done on the topic. To this end, creating a literature review is vital to any research study. Recall, a literature review is a section of your research paper or research process which collects key sources and previous research on your research question and discusses the findings in synthesis with each other. The literature review can raise both previous research that has been done on a topic, as well as best practices regarding research methodologies given the question you’ve chosen. In most cases, the literature review itself will have its own introduction, body and conclusion. The introduction will explain the context of the research question and a thesis which will tie together the research you’ve collected. The body will summarize and synthesize all the research, ideally in either chronological, thematic, methodological or theoretical order.

For instance, maybe it makes the most sense to arrange the research you’ve looked at in chronological order, beginning with the early research and culminating in the most recent research on a topic. Or, maybe your research contains a number of interrelated themes, in which case, it may be ideal to introduce previous research as it is categorized based on its theme. Or, perhaps the most interesting part of your research will be the research methods previously employed to answer the research question. In this case, doing a survey of the previous research methods might be ideal. Finally, it’s possible that the literature review may be best organized by considering previous theories that have existed in relation to your research question. In this case, introducing the existing theories in order would be most helpful to your reader and to your understanding of the research context. In general, it’s important to consider the best way to showcase, summarize and synthesize previous research so it is clear to the readers and other scholars interested in the topic.

Step Three: Theory and Hypothesis Development

Given the research question and your exploration of previous research that has been organized in the literature review, it is now time to consider the theories and hypothesis that you will be using. Usually, the theory helps build your hypotheses for the study. Recall, a theory is a statement that explains how the world works based on experience as an observation.

A scientific theory consists of a set of assumptions, hypotheses, and independent (explanatory) and dependent (outcome) variables. First, assumptions are statements that are taken for granted. These statements are necessary for the researchers to proceed with their research so they are not usually challenged. For example, many international relations scholars assume that the world is anarchic, meaning that there is no meaningful central authority to enforce the rules of law. Also, scientific researchers are implicitly assuming that an objective truth exists. If we were to start a scientific inquiry by testing the assumption about the existence of an objective truth, we will never be able to proceed with the actual question of interest since such an assumption is not really testable. Again, we typically do not challenge a set of assumptions in scientific research.

Political science research involves both generating and testing hypotheses. Researchers may start with observing many cases that relate to a topic of inquiry. There are several methods. First, through inductive reasoning, scientists look at specific situations and attempt to form a hypothesis. Second, political scientists may also rely on deductive reasoning, which occurs when political scientists make an inference and then test its truth using evidence and observations. Recall, a hypothesis is a specific and testable prediction of what you think will happen; a hypothesis, or set of hypotheses, will describe, in very clear terms, what you expect will happen given the circumstances. Within the hypothesis, variables will be identified. Remember, a variable is a factor or object that can vary or change. Again, as political scientists are concerned with cause-and-effect relationships, they will divide the variables into two categories: independent variables (explanatory variables) are the cause, and these variables are independent of other variables under consideration in a study. Dependent variables (outcome variables) are the assumed effect, their values will (presumably) depend on the changes in the independent variables.

Steps Four and Five: Testing and Analysis

The testing of a theory and set of hypotheses will depend on the research method you decide to employ. This will be discussed in Section 2.2: Four Approaches to Research. For our purposes, the basic research approaches of interest will be: the experimental method, the statistical method, case study methods, and the comparative method. Each one of these methods involves research questions, use of theories to inform our understanding of the research problem, hypothesis testing and/or hypothesis generation.

Similarly, analysis of outcomes can be reliant on the research methodologies employed. As such, analysis is also considered in Section 2.2. Overall, analysis of the findings are critical to the advancement of the field of political science. It is important to interpret findings as accurately and objectively as possible in order to lay the foundations for further research to occur.

Step Six: Reporting of Findings

A critical feature of the scientific method is to report your research findings. Granted, not all research will result in publication, though publication is often the goal of research that hopes to extend the political science field. Sometimes research, if not published, is shared through research conferences, books, articles or digital media. Overall, the sharing of information helps lend others to further research into your topic, or helps spawn new and interesting directions of research. Interestingly, one can compare a world where research is shared versus where it was not shared. During the flu pandemic of 1918, many of the countries of the world did not have freedom of the press, including the United States, which had implemented Sedition Acts in the midst of World War I. In the midst of a hindered press and the lack of freedom of speech, many doctors around the world were not able to communicate their ideas or treatment plans for handling the flu pandemic at that time. Inundated with swarms of patients, flummoxed by the nature of a flu that was killing young, healthy adults, but largely sparing older individuals, doctors were trying all sorts of treatment methods, but were unable to broadly share their results of what worked and didn’t work well for treatment.

Contrast this with the COVID-19 pandemic, many doctors were working on treatment plans worldwide, and were able to share their ideas on how to best treat COVID. Initially, there was a heavy reliance on ventilators. In time, some doctors found that repositioning patients on their stomachs may be one way to avoid a ventilator and bide time for the patient to recover without having to resort to a ventilator right away. All told, the sharing of results is critical to learning about a research area or question. If scientists, as well as political scientists, are unable to share what they’ve learned, it can stall the advancement of knowledge altogether.