4.1: What is Democracy?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 135838

- Dino Bozonelos, Julia Wendt, Charlotte Lee, Jessica Scarffe, Masahiro Omae, Josh Franco, Byran Martin, & Stefan Veldhuis

- Victor Valley College, Berkeley City College, Allan Hancock College, San Diego City College, Cuyamaca College, Houston Community College, and Long Beach City College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define democracy.

- Recognize the origins and characteristics of democracies.

- Distinguish between (the) types of democracy.

Introduction

“Many forms of Government have been tried, and will be tried in this world of sin and woe. No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.…”

— Winston Churchill, November 11th, 1947

More than half of the governments currently in existence operate under some variation of democracy. The global trends towards democratization worldwide during the twentieth century prompted some to conclude that democracy is simply the best, or most ideal, form of government. Indeed, near the end of the twentieth century, political scientist Francis Fukuyama wrote a book entitled, The End of History and the Last Man, where he argued humanity had reached the end of history because many countries had adopted forms of liberal democracy. His book was a best-seller which energized many about the prospects of a world which embraces democracy and will not again suffer the likes of major World Wars and conflicts. Twenty years after this publication, however, and in light of events like the September 11th attacks on the United States, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the rise of China, the backsliding of Russia, the COVID-19 pandemic and the eventual fall of Afghanistan back to authoritarian rule, Fukuyama mostly retracted his conclusion that the world had accepted democracy as the standard. Instead, he now asserts that issues related to political identity now threaten the security of geo-political stability. The many challenges facing democracy, democratization, and democratic backsliding (discussed in Chapter 5), prompts us to take a hard look at democracy, its types, its institutions and models, and various manifestations throughout the world. Is democracy the best form of government? What are its advantages and disadvantages?

Francis Fukuyama is an American Political Scientist, economist, and author of books and journal articles. From left to right, his 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man, prompted discussion over whether the world had reached the end of history because so many countries had been adopting liberal democracy as their form of government. One of his more recent books, Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment, came out in 2018, and his conclusions began veering away from the belief that the world had accepted liberal democracy. Instead, political identity and the weight of historical disputes potentially impede global geopolitical potential for long-term peace.

Origins, Definitions and Characteristics of Democracy

Although there is evidence of what anthropologists have designated primitive democracy, wherein small communities have face-to-face discussions in order to make decisions, as far back as 2,500 years ago, the first formal application of democratic institutions and processes is generally attributed to ancient Greece. Athens, Greece is generally credited with being the birthplace of democracy. In its simplest terms, democracy is a government system in which the supreme power of government is vested in the people. Democracy comes from the Greek word, dēmokratiā, where “demos” means “people”, and “kratos” meaning “power” or “rule.” Prior to the formation of legal reforms, Athens had operated as an aristocracy.

An aristocracy is a form of government where power is held by nobility or those concerned to be of the highest classes within a society. Aristocracy proved troublesome for Athens, and the people eventually rallied under an Athenian leader named Solon (circa 640 - 560 B.C.E.). In trying to meet the demands of the people, Solon attempted to satisfy all classes of the Athenian population, rich and poor alike, to devise a form of government which satisfied all. To this end, in 594 B.C.E., Solon created legal reforms and a constitution, which provided the foundations for citizen participation in government affairs, and abolished slavery of Athenian citizens. Under this construct, adult males who had completed their military training were given the right to vote, and as much as 20% of the population was considered to be active in making laws. Eventually, democracy in Athens failed, due to both internal and external factors. Internally, there was heavy criticism that the aristocracy was still in force, and able to pervert and manipulate legal outcomes to their own benefit. Further, the works of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, all of whom were critical of the merits and feasibility of democracy, led to the erosion of trust in democracy in Athens. Generally, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, though they had their own unique critiques of democracy, tended to value political stability over the potential of “rule of the mob.” Externally, and tied to the prospect of political stability, Athens faced frequent challenges to its democracy from the outside. The Peloponnesian War, the changes in leadership from King Phillip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great, and finally, the rise of the Roman Empire, all are also attributed to the eventual decline of democracy in ancient Greece. After the fall of democracy in Greece, the prospect of democracy did not re-emerge as a feasible, or even desired, option until the early modern era in the 1600s.

Ancient concepts and manifestations of democracy differ greatly from modern conceptualization and application of democracy. One of the key differences is in the way power from the people is channeled; the difference becomes apparent in comparing a direct democracy versus an indirect democracy. A direct democracy enables citizens to vote directly, or participate directly, in the formation of laws, public policy and government decisions. In this system, citizens personally get involved in all aspects of politics, and are able to change constitutional laws, recommend referendums and make suggestions for laws, and mandate the activities and actions of government officials. To some extent, Athens exercised a direct democracy in that adult male citizens, who had completed their military training, could participate directly in the making of laws. It was not a 'perfect' democracy in that not all citizens, male and female, rich and poor, could participate, but it did have a mechanism for a certain class of citizen participating, i.e. males. In contrast, indirect democracy channels the power of the people through representation, where citizens elect representatives to make laws and government decisions on their behalf. In this scenario, citizens of the country are granted suffrage, which is the right to vote in political elections and propose referendums. In a healthy democracy, elections are both free and fair. Free elections are those where all citizens are able to vote for the candidate of their choice. The election is free if all citizens who meet the requirements to vote (e.g. are of lawful age and meet the citizenship requirements, if they exist), are not prevented from participating in the election process. Fair elections are those in which all votes carry equal weight, are counted accurately, and the election results are able to be accepted by parties. Ideally, the following standards are met to ensure elections are free and fair:

Before the Election

- Eligible citizens are able to register to vote;

- Voters are given access to reliable information about the ballot and the elections;

- Citizens are able to run for office.

During the Election

- All voters have access to a polling station or some method of casting their vote;

- Voters are able to vote free from intimidation;

- The voting process is free of fraud and tampering.

After the Election

- Ballots are accurately counted and the results are announced;

- The results of the election are accepted / respected / honored.

The integrity of the election is of paramount importance in democracies, for if the process is not found to be free or fair, it violates the core principles of what constitutes a democracy: by the people, for the people.

Indirect democracy is what most democratic countries today practice, partly because of logistics (In the U.S., how would every single adult citizen directly participate in the making of laws? Would requiring a vote for every decision be time efficient?), and to another extent, a question over whether voting is always the best option for determining just, equitable or ideal outcomes. In a representative democracy, citizens, to some extent, outsource the power of lawmaking to those who, ideally, either have expertise in making laws or who may be granted a greater depth of information in order to make decisions.In this sense, not every citizen necessarily wants to be involved in every government decision, but would prefer selecting a representative to getting political work done. Further, although most democratic countries do practice indirect democracy, there are often some mechanisms that align with some characteristics of a direct democracy. For instance, the U.S. has a representative democracy, but voters in some states have the ability to put forth initiatives and referendums, also referred to as Ballot Propositions. Overall, democracy’s definition, if practiced as indirect democracy, can be understood as: a government system in which the supreme power of the government is vested in the people, and exercised by the people through a system of representation which includes the continued practice of holding free and fair elections.

Importantly, democracy has a number of characteristics which can be central to understanding the variation in democracies that exist worldwide today. These differences also highlight the difference between concepts of ancient democracy versus contemporary democracy. Ancient democracy had no concept or foundations for widespread suffrage or the protection of civil liberties. Some of these modern accepted democratic themes include (but are not limited to): free, fair and regular elections (ideally, with the inclusion of more than one viable political party), respect for civil liberties (freedom of religion, speech, the press, peaceful assembly; freedom to criticize the government) as well as the protection of civil rights (freedom from discrimination based on various characteristics deemed important in society). Democracies which not only facilitate free and fair elections, but also ensure the protection of civil liberties are called liberal democracies. Although these are the general themes, there is still ample debate among scholars about the importance and weight of these characteristics. Larry Diamond, an American political sociologist and a scholar of democratic studies, put forth the following four characteristics which make a democracy, a democracy. A democracy must include:

- A system for choosing and replacing the government through free and fair elections;

- Active participation of the people, as citizens, in politics and civic life;

- The protection of human rights of all citizens;

- A rule of law in which the laws and procedures apply equally to all citizens. (Diamond 2004)

Karl Popper, an Austrian-British academic and philosopher (whom you may recognize from Chapter 2 for his work on the nature of inquiry and the recognition of falsification theory), had a more blunt definition for democracy, “I personally call the type of government which can be removed without violence ‘democracy,’ and the other, ‘tyranny.’ (Popper 2002). Instead of citing specific characteristics of democracy, which Popper was hesitant to do given the wide variation in democracies that exist, he simply contrasted it with outright tyranny. In general, Popper emphasized the importance not in how the people could exercise authority, but that they have access, availability and opportunity, through some means, to control their leaders without violence, retribution or revolution.

Other scholars have noted more rigid qualifications for democracy. In looking at the world of Robert Dahl, Ian Shapiro and Jose Antonio Cheibub, all political scientists, they assert that every vote in a representative democracy must carry equal weight, and that the rights of citizens must be equally protected by a well-defined and clear “law of the land;” in most cases, the “law of the land,” rests with a written constitution. The rights and liberties of citizens must be protected by the law of the land. (Dahl, Shapiro, Cheibub, 2003)

Overall, there are hundreds of critiques and frameworks for defining democracies and noting its characteristics, and scholars are generally not in full agreement on what constitutes a perfect democracy. Nevertheless, reaching some consensus on the characteristics is important if scholars want to advance the understanding of regime types like democracy. The difference in perception of democracy can be seen in how some organizations choose to measure democracy across countries. At present, there are at least eight organizations which attempt to quantify the existence and health of democracies worldwide. These eight include: Freedom House, Economist Intelligence Unit, V-Dem, the Human Freedom Index, Polity IV, World Governance Indicators, Democracy Barometer, and Vanhanen’s Polyarchy Index. In Table 4.1.1, a few of these are highlighted based on what they identify as main characteristics of democracy. This table shows the differences in components considered when trying to measure democracy. From left to right, Freedom House, Economist Intelligence Unit, and Varieties of Democracy; all are organizations which attempt to determine whether countries are democratic and assess the strength of their democratic institutions.

Table 4.1.1: Measuring Democracy

| Index | Freedom House | Economist Intelligence Unit | Varieties of Democracy |

| Components/ Characteristics Measured |

-Elections -Participation -Functioning of Government -Free Expression -Organizational Rights -Rule of Law -Individual Rights |

-Elections -Participation -Functioning of Government -Political Culture -Civil Liberties |

-Elections -Participation -Deliberation -Egalitarianism -Individual Rights |

The different organizations, choosing different areas of emphasis and weight for characteristics of democracy, yield different outcomes in terms of identifying whether a country is a democracy, as well as judging the healthiness of a democracy. For instance, as of 2018, the Varieties of Democracies Project finds there are currently 99 democracies, and 80 autocracies. Autocracies are forms of government where countries are ruled either by a single person or group, who/which holds total power and control. For this same time-period, the Polity IV Index disagrees, finding 57 full democracies, 28 mixed-regime types, and 13 autocratic regimes. Importantly, the Polity IV Index does not take suffrage into consideration as a meaningful indicator of democracy. Freedom House also arrives at different outcomes for this same time-period, asserting that 86 countries are democracies, with 109 non-democracies. Finally, the Economist Intelligence Unit found 20 countries to be fully democratic, and 55 countries have “flawed democracies.” Given that scholars and these organizations have acknowledged that different types of democracies exist, it is now useful to discuss these types, as well as the implications for these types on the institution of democracy.

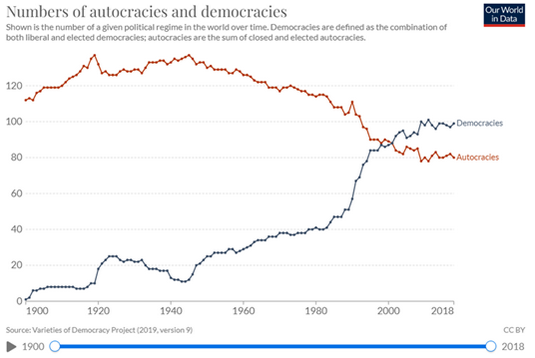

The number of democracies has significantly grown worldwide since 1900. Political scientists have sometimes called jumps in the number of democracies ‘waves.’ In this way, there have been three major waves of democratization: World War I (First wave, 1828-1926), with subsequent “waves” of democratization coming following World War II (Second wave) and the democratic transitions in Portugal, Spain and Latin American in the 1970s (Third wave).

Types of Democracy

The different organizations, choosing different areas of emphasis and weight for characteristics of democracy, yield different outcomes in terms of identifying whether a country is a democracy, as well as judging the healthiness of a democracy. For instance, as of 2018, the Varieties of Democracies Project finds there are currently 99 democracies, and 80 autocracies. Recall, autocracies are forms of government where countries are ruled either by a single person or group, who/which holds total power and control. For this same time-period, the Polity IV Index disagrees, finding 57 full democracies, 28 mixed-regime types, and 13 autocratic regimes. Importantly, the Polity IV Index does not take suffrage into consideration as a meaningful indicator of democracy. Freedom House also arrives at different outcomes for this same time-period, asserting that 86 countries are democracies, with 109 non-democracies. Finally, the Economist Intelligence Unit found 20 countries to be fully democratic, and 55 countries have “flawed democracies.” Given that scholars and these organizations have acknowledged that different types of democracies exist, it is now useful to discuss these types, as well as the implications for these types on the institution of democracy.