1.5: The People of Texas

- Page ID

- 129178

Every ten years, the U.S. conducts a census to try to count every person living in the country. We need those numbers to reapportion the seats in the U.S. House of Representatives and to determine how many seats each state will receive. We need the numbers to determine the number of electoral college votes a state will get when electing the president. And, these numbers are used to redraw congressional and state legislative boundaries to account for population shifts. In 2016, Texas received $59.4 billion based on its population for federal programs like Medicaid, Federal Student Loans, Federal Pell Grants, School Meals Programs, High Planning, and more.\(^{26}\) An undercount of just one percent could result in a loss of millions of dollars. The census also gives us information about people of color, immigrants, children, low-income populations, and renters. Obviously, the government is worried about the 2020 census because of the pandemic and the very real possibility of an inaccurate count. In this section, the discussion will revolve around the demographics of the state and those people of Texas.

Population

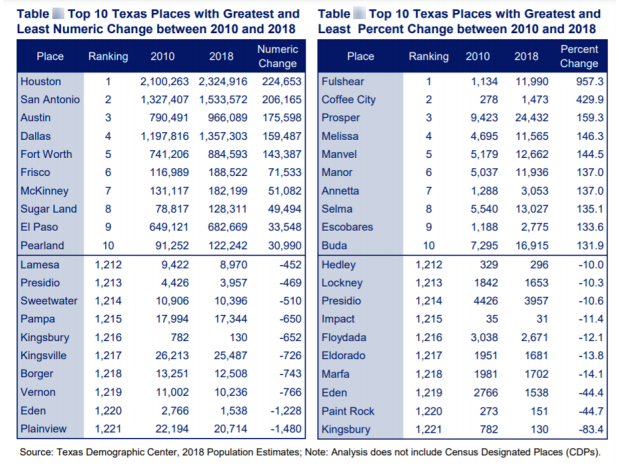

Texas is the second most populous state in the United States, after California. In December of 2019, the Texas Demographic Center estimated the population for Texas at 28,702,243 which represents an almost fifteen percent increase from the census count of 25,145,565 in April of 2010. For every year since 2006, Texas had added more population than any other state, with most of that growth in the big cities. The population density in 2019 stood at almost 110 residents per square mile of land area, higher than the national population density. However, most of the population live in the major cities such as Houston, San Antonio, Dallas-Fort Worth, and Austin. The majority of the counties experienced population growth, especially those metropolitan counties (Table 1.5.1).

As Table 1.5.1 shows, most of the population growth came from the large urban cities. Those top ten cities added over one million people in population between 2010 and 2018 which accounted for thirty-two percent of the population growth in Texas. As the bottom of the table shows, those areas with the greatest population losses are mostly rural and sparsely populated. This is particularly true in the Panhandle and West and East Texas.

Table 1.1 also shows the top ten areas with the fastest growth rates and most of them are in the suburban areas. For instance, Fulshear is located in Fort Bend County adjacent to Houston and had the fastest rate of growth, over ten times from that of 2010. Coffee City is located in the Dallas-Fort Worth area and grew over five times from that of 2010. And the rest of those areas saw at least a thirty percent increase in their populations. At the bottom of the table, the decline is most evident in the rural areas not adjacent to a metropolitan area. Even though Texas added over 3.55 million people between 2010 and 2018, it is not evenly distributed across race and ethnicity.

Race and Ethnicity

According to population estimates from the United States Census released in July of 2019, nonHispanic Whites account for about 41.2 percent, Hispanics 39.7 percent, African Americans 12.9 percent, Asian Americans 5.2 percent, and American Indians one percent of the total population in Texas. The remainder would include two or more races or other. Texas is one of only six states to be a majority minority state, which means Hispanics, African Americans, Asian Americans, and American Indians combined equal more population (58.8 percent) than the nonHispanic White population (41.2 percent). It is expected that Hispanics will become the largest population group in Texas as early as 2022.

Non-Hispanic Whites had a decline in population while Hispanics experienced an increase. Between 2010 and 2018, Hispanics saw an increase of almost two million people. By contrast, African Americans saw an increase of 541,760 people, Whites saw an increase of 484,211, and Asians saw an increase of 473,193. While the Hispanic community is growing across the state, forty-seven percent live in the state’s five biggest counties—Harris, Bexar, Dallas, Tarrant, and Travis. Although the numbers are smaller, the rate of growth of the Asian population has seen the largest increase from 2010 at forty-nine percent. The Hispanic population has grown twenty percent, the Black population nineteen percent and the White population four percent. The number of Blacks continue to grow, but their share of the population has remained fairly stable at just over twelve percent.

Almost all Texans are immigrants. They just arrived at different times making Texas the diverse state it is today. During the 300 years of Spanish rule, people came from Spain, the West Indies, the Canary Islands, but mostly from Mexico. Then the Mexican government opened up Mexican Texas for immigration to keep control of the area. After independence, waves of Anglo and European people came to Texas. Finally, by the end of the twentieth century, non-European immigration became the settlement story.

Non-Hispanic Whites

Between 1821 and 1835, Stephen F. Austin and a few others settled about 30,000 Anglo-Americans in Texas during a period referred to as Anglo-American Colonization. Cotton farming was prevalent in eastern Texas and trade was established with the U.S. through New Orleans. Throughout the nineteenth century, the availability of cheap land continued to attract settlers from the U.S. Johann Friedrich Ernst bought land from Austin in 1831 and attracted more German settlers due to the glowing letters he wrote home. Henri Castro also brought Germans to Texas, establishing a large colony in Castroville, southwest of San Antonio. The Society for the Protection of German Immigrants in Texas was formed to raise money to buy land grants and over 7,000 immigrants from Germany followed. Wars in Europe continued the immigration bringing the English, Irish, Dutch, Poles, Swedes, Norwegians, Czechs, Italians and the French to the U.S. and Texas. The diverse European immigrants can still be found in town names, architectural styles, music and the food in Texas.

Most Anglos who moved to Texas believed it would eventually become part of the United States, but after independence in 1836, it took almost ten years to achieve statehood. As a Republic, Texas had no political parties. Sensationalistic newspapers advocated for or against particular personalities, like Sam Houston, the military hero who had won independence at the Battle of San Jacinto. Texas finally did become a state in 1846, but despite the objections of proUnionists like Houston and others, especially the Bexar County Germans, Texas was drawn into the Civil War, seceding from the Union February 1, 1861.

The Reconstruction period between1865-1899 was tumultuous and bitter for former Confederates. Union troops occupied the state, and an autocratic E. J. Davis was appointed governor to enforce loyalty to the Union of former Confederates and protect the rights of newly freed African Americans. Once the old elites had regained power, Texas aligned with the southern Democratic Party and remained a Democratic one-party state for a hundred years.

Hispanic Americans During the early 1700s, the Spanish sent more than thirty expeditions into Texas. San Antonio had a military post and a mission (the Alamo). Missions were also established in Nacogdoches to the east, Goliad in the south, and El Paso in the west. With Mexican independence in 1821 the Mexican government moved from monarchy to republic to dictatorship, with numerous coups in between, seemed distant at best. But Texians (Anglo colonists) and Tejanos (Texans of Mexican descent) chafed as President Santa Anna sought to increase taxes and centralize power in Mexico City. These conflicts evolved into a full-scale revolt, and fought together for independence from Mexico.

The Hispanic population in Texas became Mexican Texans after Texas won its independence n 1836. Then when Texas became a part of the U.S., Mexican Texans became Mexican Americans. Today Texans may identify as Hispanic, Latino, Mexican American, Mexicano, Chicano, or Tejano. Thousands of Mexicans from El Paso to the Valley where the Rio Grande River meets the Gulf of Mexico, became Texans. After the Civil War, many Mexican workers came to Texas to work on the railroads and on farms and ranches. This immigration expanded even more with the Mexican Revolution of 1910 when refugees escaped Mexico to come to Texas. Many Mexican Americans in Texas have roots back to early frontier settlement and have played a major role in the culture, economy, and political life of Texas from the beginning.

Large numbers of the Hispanic population can be found in the cities of Houston, Dallas/Fort Worth, San Antonio, Austin and El Paso. Also, large numbers in the southern Rio Grande Valley and in the counties bordering Mexico. Forty-seven percent of the Hispanic population live in the state’s five largest counties—Harris, Bexar, Dallas, Tarrant ,and Travis. The population has grown by more than two million since 2010 to a total of about 11.5 million, and the Texas demographer predicts that Hispanics will be the state’s largest population group by the summer of 2021. In 2018, Texas gained nine Hispanic residents for every additional White resident.\(^{27}\)

African Americans

People of African descent have been in Texas since the Spanish Colonial Era. Their population expanded during the period of Mexican rule as the Anglo immigrants brought enslaved people to work in the fields. By 1860, thirty percent of Texas’s population were enslaved peoples.\(^{28}\) The Confederacy lost the Civil War in 1865, and on June 19 that year— Juneteenth—word of the Emancipation Proclamation reached Texas. After the Civil War, many stayed as laborers or sharecroppers, while other large groups settled in the segregated parts of the large cities, especially Dallas and Houston. During Reconstruction, thirty-five African Americans held elected office in the Texas legislature. After Reconstruction, those in power passed segregationist Jim Crow laws that curtailed the rights of African Americans and their engagement in political life. These laws were in effect until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were passed under President Lyndon B. Johnson, making segregation illegal and outlawing discrimination at the voting booth.

Texas ranks tenth in the nation with high political engagement among African Americans. There are approximately 1.5 million Black voters in Texas, more than any other state in the country and they form the base of the Texas Democratic Party. The party issued the following statement before the November 2020 election, “Make no mistake about it, Black voters are the backbone of the Texas Democratic Party.” \(^{29}\) In 2020, data indicated that eightynine percent of Black voters supported President Biden.\(^{30}\) Turnout in the election showed that the Black vote was almost exactly the same as the Anglo vote with 58.8 percent and 58.6 percent respectively. \(^{31}\) More important, organizational efforts by Black groups have created outreach plans to be sure they are registered to vote, that they do vote, and that they vote Democratic. Another statement by the Texas Democratic Party, “The Texas Democratic Party couldn’t be more thrilled to partner with Powered By People and the Texas Coalition of Black Democrats to launch the most expansive Black voter contact program in Texas history. For too long, Black voters have been underrepresented in outreach and investment by organizations that haven’t truly harnessed or understood the power of the Black vote.”\(^{32}\)

Asian Americans

Vietnamese Americans, Chinese Americans, Filipino Americans, Korean Americans and Japanese Americans dominate the Asian population in Texas. The Asian Texas population has grown primarily in western Houston, the suburban areas of Dallas and Arlington, and Austin. There is also a large number of Asian Texans long the Gulf Coast because the shrimp and fishing industry attracted thousands of Vietnamese, Filipinos, and Chinese during the 1970s and 1980s to escape their country’s government. The Vietnamese were particularly drawn to the Gulf Coast due to the similarity of the climate to home. Families worked together to purchase shrimp boats and to bring other families to Texas from Vietnam. Over 210,000 Vietnamese live in Texas and Vietnamese is the third most spoken language in Texas.

Neither of the political parties have done much to reach the Asian Texas population until recently. In the 2020 election, fifty-one percent turned out to vote, almost eight percent higher than the national average turnout for this ethnic group.\(^{33}\) And sixty-three percent supported President Biden.\(^{34}\) Asian Texans have traditionally voted Republican, but that seems to be changing as well. And although only about five percent, or 1.5 million people are Asian Texan, they are a fast-growing group in the state.\(^{35}\) While there are differences among the different ethnic groups, they tend to end up behind one candidate. Vietnamese Americans and Filipino Americans tend to be slightly more conservative while the Indian Americans and Japanese Americans tend to be more progressive. In the future, both political parties will be courting this group.

American Indians

American Indian settlements have been discovered in Texas that are well over 12,000 years old. American Indians are not a single group but comprise many cultures and languages, with a wide variety of housing and food. After a rich history, only three federally recognized tribes still have reservations in Texas—the Alabama-Coushatta in Livingston, the Kickapoo in Eagle Pass, and the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo in El Paso.

The removal of indigenous peoples from Texas took place around the same time as the forced relocation of tribes from all across the country known as the Trail of Tears. When the second president of the Republic of Texas took office in 1838, Mirabeau B. Lamar declared an “exterminating war” on American Indians.\(^{36}\) Although the reasons given were attacks on settlers—especially in Central and West Texas—and suspicions that the Cherokee in East Texas would unite with Mexico,\(^{37}\) the real purpose of removing American Indians from the Republic was, as it had been thoughout the history of broken treaties in America, to acquire their land. Reservations were established for resettlement and when they closed, most of the occupants were relocated to reservations in Oklahoma.

The oldest remaining reservation in Texas is the Alabama-Coushatta with about 650 residents. The other two reservations are along the Rio Grande River received recognition in 1960. The Tiguas were brought from the area around Albuquerque, New Mexico, and live on trust land in El Paso County and have about 1,400 residents. The Kickapoos came from the Great Lakes region and received their land in 1985 and have about 650 residents.\(^{38}\)

Between the 1950s and 1980s, the federal government resettled about 40,000 American Indians in the Dallas/Fort Worth area to begin a program of integration into American culture. Today, there are about 4,000 Indians in that area. Linda Pahcheka-Valdez was nine years old when she moved from Cache, Oklahoma to Dallas. “They put us in areas like the West Dallas projects, and in the projects, our people became aware of each other,” she said.\(^{39}\) “We have four Native American Indian churches here in Dallas. And we have a tendency to find each other.”\(^{40}\) Tribal Council Chairperson Cecilia Flores of the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe acknowledges that voter turnout has been low. When an electronic bingo facility, which is run by the tribe and employs over 700 local people, was threatened with closure over conflicts with federal laws, the tribe began to organize. The hope is to increase voter participation so that their issues will be taken more seriously. “We’re doing a lot more voter education and letting people know that they do have a voice and that these issues that are out there on the table now,” said Flores, who is also a U.S. Air Force veteran.\(^{41}\) “We can have some influence if we have a voice in our voting and who our representatives are in Congress and at the state level.”\(^{42}\) Nationally, voter turnout among American Indian and Alaska Native voters is about one to ten percentage points below other racial and ethnic groups.

Age and Ability

Urban growth has been partly fueled by young people.\(^{43}\) Young people are also moving to West Texas, South Texas, and the Panhandle for jobs in the oil industry, making Texas younger than the average state. Almost twenty-six percent of Texas’s population is age eighteen or younger, which really lowers the median age of Texans. The median age in Texas is 34.4 years old; the median age nationally is 37.8.\(^{44}\) Since 2010, Texas has had the nation’s second highest population growth of people under eighteen years old.

In addition to becoming more diverse and urban and younger, however, as Texas grows, it also becomes older. Most of the aging is taking place in the rural counties as baby boomers are aging into the sixty-five plus range. Those sixty-five and older had the greatest increase with slightly more than one million. Almost thirteen percent of Texans are over the age of sixty-five and that number is expected to increase to twenty percent by 2050 as medical advances enable people to live longer. Texas Health and Human Services reports that this expected increase will mean an increase in all types of health and services such as health care, home care, personal care and long-term care.

With almost the same percentage, almost thirteen percent of all Texans have been identified as having a disability. Texas Health and Human Services defines a disability as people who are limited in one or more of major life activities—hearing, seeing, thinking or memory, walking or moving, taking care of personal needs (bathing, feeding, dressing) or living independently. Some are born with a disability; others are the result of accidents, injuries or just getting older.

The aging population along with the disabled population present challenges in meeting their needs. It is the goal of Texas Health and Human Services to help people in both of these groups to live independently in their own homes or communities when possible, help family caregivers the tools to care for these individuals, and to provide information about state and/or federal benefits and legal rights.

Income

In 2018, Texas enjoyed the fastest income growth in the U.S. Incomes expanded six percent as compared to 4.2 percent for other Americans.\(^{45}\) 2019 was another good year—overall median income was up, the number of families living in poverty decreased, and unemployment rates were lower. Nevertheless, even before the pandemic, the overall poverty rate in Texas is about fifteen percent, significantly higher than the 9.2 national average.\(^{46}\) Data showed that since the pandemic the number of food insecure households has doubled and the unemployment rate rose to 12.8 percent, though this is still below the national average of 14.7 percent.\(^{47}\) The number of children living in poverty comprise about twenty-two percent; the senior poverty rate is about eleven percent; women living in poverty is about sixteen percent, and about nine percent are living in extreme poverty. Approximately fifteen percent of Texans are food insecure, seventeen percent are uninsured, twenty-seven percent have low wage jobs, and thirty-six percent of working families are still under 200 percent of the poverty line. All of this means that the need for social welfare programs is high. Table 1.5.2 shows the number of Texans receiving assistance from a variety of these programs.

| Participation in Federal Programs | |

| Adults and children receiving welfare (TANF) | 61,621 |

| Children receiving food stamps (SNAP) | 2,564,138 |

| EITC recipients | 2,600,000 |

| Families receiving child care subsidies | 62,600 |

| Households receiving federal rental assistance | 277,000 |

| Households receiving LIHEAP (Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program) | 142,758 |

| Number of children enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP | 3,286,092 |

| Number of women and children receiving WIC (Women, Infants and Children supplemental nutrition program) | 746,246 |

| Participants in all Head Start programs | 72,087 |

Religion

Since the mid-1830s, Protestantism has dominated the religious life of Texans, although Catholicism was the first established religion in Texas. After achieving independence, Methodist, Baptist, Presbyterian, and Episcopal churches and parishes spread across the state. These denominations were certainly interested in personal evangelism, but they were also concerned with education, slavery and temperance. When Martin Ruter, Superintendent of the Methodist Texas Mission came to Texas in 1837, he believed that alcohol was to blame for the unruliness in Texas. He declared “profaneness, gaming, and intemperance” to be the “prevailing vices against which” Texans had “to contend.”\(^{48}\) To many pastors and priests, only total prohibition would be the desired outcome.

The Texas churches valued learning and they began establishing schools at an early date. The Catholic church had been teaching at the missions from the beginning of Texas mission history. Later, Protestant Sunday schools were present in Moses and Stephen Austin’s colonies. Churches founded a number of academies, institutes, colleges, and universities.

Mexican Texans have overwhelmingly been Roman Catholic, while African Texans have overwhelmingly been Baptist. After the Civil War, White congregations were divided over the decision to retain the former slaves within the congregations or to have them form their own churches. As one Houston Baptist said, “to exclude freedmen from White churches would leave them vulnerable to the combined evil of ignorance, superstition, fanaticism, and a political propagandism more dangerous and destructive to the best interests of both Whites and Blacks than Jesuitism itself.”\(^{49}\) African American Texans, on the other hand, wanted their new freedom and formed their own independent churches.

Modern Texans are more religious than their ancestors and more Texans belong to organized religious bodies than Americans at large. About sixty percent of Texans say religion is important in their lives and that can affect voting. As political scientist Matthew Wilson from Southern Methodist University put it, “I think as we move into the future we are going to see more of a kind of secularist, non-religious pushback against some things. So there will be changing dynamics, but religion is going to continue to be an important part of Texas politics for the foreseeable future.”\(^{50}\)

Education

Seventy-one percent of jobs in the future will require some college, but only thirty-two percent of high school graduates in Texas go on to some kind of post-secondary education, slightly lower than the national average of thirty-five percent, though still fifth among states for those who attained some college.\(^{51}\) Higher educational attainment is associated with higher earning power, with college degree recipients earning ninety-eight percent more on average.\(^{52}\) Austin-Round Rock is in the top ten for educational attainment nationally; McAllen-Edinburg Mission and Brownsville-Harlingen rank among the lowest, respectively.\(^{53}\) Discouragingly, Texas has the largest gender gap in educational attainment, and the seventh largest racial gap.\(^{54}\)

Texas is not unique when it comes to the issues it faces in educating its students, such as how to finance education, standardized testing of students, student population growth, school choice, setting school calendars, and dealing with aging infrastructure. However, as the Eighty-Seventh Texas Legislature meets in 2021, it must deal with a year of a pandemic leaving many students falling behind. At this point we do not have enough data to accurately predict just how far behind these students are, but it will be significant.

The first major hurdle is how to administer the State of Texas Assessment of Academic Readiness (STAAR) standardized test. Texas is requiring all districts to allow in-person learning for all students who want it and a survey taken at the end of October, 2020 showed 2.8 million students were in the classroom. But with a total of 5.5 million students, millions were still learning online. Current estimates say students are three months behind, but many fear that is a low estimate. The STAAR test was canceled in the spring of 2020 after the pandemic closed schools and learning was moved online. Many are calling for it to be canceled in 2021 as well. The Texas Education Agency has said that students must show up in person to take the STAAR test.\(^{55}\) By mid February 2021, the Commissioner altered his earlier requirement. Those students whose parents have kept them home as virtual learners during the pandemic do not need to take the STAAR test after all. That will not apply to the graduating seniors in the class of 2021, those students who do not show up to take the exam in person, whether they are still learning virtually will not graduate.\(^{56}\) The Texas Education Commissioner says that the data collected from the tests will show the educational gaps caused by the pandemic. Texas is moving ahead with plans to have all state required standardized tests online by 2022, with exclusions for students with disabilities or other special needs. However, the costs will affect districts across the state disproportionately, especially those that are small and rural.

Schools are struggling to find enough substitute teachers during the pandemic when the coronavirus has affected Texas teachers. Many administrators, school staff and others without credentials have been sent into the classroom. In some instances, other teachers are “adopting” another teacher’s class by posting lessons and recording videos for both classes. This is causing additional stress on students who do not know when or whether their teacher will be back in the classroom.

In the last legislative session, a bill was passed which made big changes to way schools are funded and added $6.5 billion into public education. That bill was passed while the Texas economy of booming, but will be much more difficult after a pandemic 2020 and high unemployment. Families and businesses have had to make cuts, and it is reasonable to expect that schools will also have to make cuts. There is no doubt that this legislative session will have to make tough decisions.

Gender

The population is almost evenly split on gender, with 49.6 percent male (13,625,413) and 50.4 percent female (13,843,701), but there are more women in Texas than there are men. Like race and ethnicity, this has implications for the economic health of the citizens of Texas. According to the National Women’s Law Center, women in Texas typically make eighty cents for every dollar paid to men, Black women typically make fifty-nine cents for every dollar paid to White men, and Hispanic women typically make forty-five cents for every dollar paid to White men. All of the numbers are lower than the national average. Approximately, twenty-three percent of women aged nineteen to sixty-four are uninsured and almost twenty-five percent of women of reproductive aged nineteen to fifty-four are uninsured. Just over twenty-three percent of women in Texas reported not receiving health care at some point in the last twelve months due to cost. Finally, thirty-seven percent of female-headed households in Texas live in poverty and just over twelve percent of women sixty-five and over live in poverty.\(^{57}\)

The first large scale, well-organized political movement of women in Texas began with the creation of the Texas chapter of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1882. Their primary objective was to stop the sale of whiskey, believing as they did that liquor was destroying the family. Through their political organizing, they pushed through state prohibition and helped to secure ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1919, securing national prohibition. But the larger importance of the WCTU was that its women members learned to organize, to lobby, and to plan political strategies.

A first for the women of Texas was the election of Miriam “Ma” Ferguson as governor in 1924, although she was to be governor in name only. Her husband, Jim “Pa” Ferguson, had resigned as governor before the Senate could take action on impeachment articles due to his questionable dealings and disputes over vetoing appropriations to the University of Texas. Her opponent was Judge Felix Robertson, a staunch supporter of the Ku Klux Klan so the voters of Texas had a choice between a woman or a white supremacist—many referred to it as a choice between the bonnet or the hood! After the election, it was Jim who moved his desk into the governor’s office; it was Jim who extended his hand as politicians entered the governor’s office; and it was Jim who sat in on meetings of the state’s boards and commissions.

Texas women can also boast some other firsts. Barbara Jordan, from Houston, ws the first Black woman to be elected to the Texas Senate in 1966. In 1972, she was elected President Pro Tempore of the Senate, and she became the first Black woman in American history to preside over a state legislative body. Also in 1972, Jordan was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, becoming the first Black woman from the South to occupy a seat in Congress. Journalists and political analysts dubbed 1992 as “The Year of the Woman,” but it arrived two years earlier in Texas, with the election of Governor Ann Richards. Her 1990 campaign against West Texas oilman Clayton Williams was one of the hardest fought and most widely publicized in the nation. It was the Richards campaign that made women’s candidacies for the highest offices, in the toughest of political campaigns seem possible.

After the 2020 election, women now hold twenty-seven percent of the legislative seats with a total of forty-eight females. Over the history of the Texas legislature, 5,444 have been men while only 179 have been women. Most women in the legislature are Democrats; there are only thirteen Republican women currently serving. Here in 2021, White men are still overrepresented in the Texas legislature.\(^{58}\)

Political Implications of Demographic Change

The Democratic Party had significant control over state and local politics from the time the 1876 constitution was ratified until the 1970s. For a period of time during the 1980s and early 1990s there was some two-party competition. The election of George W. Bush in 1994 marked a decisive shift. No Democrats have won any statewide races since that year. But in 2018 and 2020 changes in demographic characteristics, such as race, income, age, the location or movements of people, signaled a real partisan divide between those loyal to the Democratic Party and those loyal to the Republicans.

Going back to the 1960s, East Texas was home to conservative Democrats and a large African American population. The Gulf Coast and Houston was heavily industrialized and was on its way to becoming the center of the oil and gas industry. Central Texas was mostly Anglo and less populated, except for Austin, and Democratic. San Antonio and South Texas was Democratic with the Hispanic population being the majority in most of the counties. North Texas with Dallas and Fort Worth represented the corporate sector and was largely conservative and Republican. West Texas, mostly Anglo except for El Paso was solidly Republican. That Texas no longer exists. The geography of Texas has remained the same, but the political geography has changed over time.

The Urban/Rural Phenomena

Between 2010 and 2018, almost three million people moved to the four metro regions, but only twenty-one percent were Anglo. Additionally, as mentioned earlier in the chapter, more and more people are moving to the urban areas from outside the state, especially California, New York, and Illinois, bringing their political cultures to Texas. More important, the four large metropolitan areas of Houston to San Antonio-Austin and up to Dallas-Fort Worth form the “Texas Triangle.”\(^{59}\) There are eight counties in the Houston area, five counties around both San Antonio and Austin, and nine counties around Dallas and Fort Worth.

Since 2000, the large metro areas have become younger and more diverse and less supportive of Republican presidential candidates while the remaining counties, except for South Texas, have become more White and older and more supportive of the GOP nominees. Democrats from the rural areas are no longer winning elections except in South Texas, along the border, and in some local elections. If you exclude the twenty-eight counties in South Texas, which are still mostly Hispanic, that leaves 199 mostly Anglo counties with smaller metropolitan areas and the rural population with small towns. Equally significant, the suburbs are changing. The suburbs of the 1960s and 1970s were mostly middle and upper class Whites moving to places that were homogenous and like-minded. Today, younger and more diverse people want to be closer to the cities and they bring a different mindset to the changing composition of the suburbs.

In 2016, former President Trump received almost seventy-five percent of the rural vote compared to less than fifty percent of the metro vote. This trend intensified in the 2018 Beto O'Rourke–Ted Cruz race for the U.S. Senate. Despite O’Rourke’s appeal to younger voters who bucked predictions of a low youth turnout and voted in record numbers, incumbent Cruz won about seventy-three percent of the rural vote but less than forty-six percent of the metro vote. Cruz lost the metro vote and still won the election, but only by a 2.6 percent margin, the smallest margin since 1996.

Then comes the 2020 election with the trend basically the same, but with a few surprises. In 2020, young people again broke turnout records, so those traditional patterns may be changing.\(^{60}\) But President Biden’s urban wins could not offset the millions of votes in the rural areas that went for Trump. In analyzing the election results, the Texas Tribune broke up the 254 counties in Texas into several groups to explain what happened. In the “Big Blue” counties of Houston’s Harris County, San Antonio’s Bexar County, Dallas County, and Austin’s Travis County voted Democratic and Biden won by almost a million votes.\(^{61}\) In the “Six Fast-Changing Suburban” counties outside of Houston (Fort Bend), Austin (Williamson to the north and Hays to the south) and Dallas-Fort Worth (Collin and Denton north of Dallas and Tarrant in Fort Worth), Biden showed improvement over Hillary Clinton’s performance in 2016, but still lost to Trump by about 2,500 votes.\(^{62}\) In 2000, all of these counties were Republican, but by 2016, three of them voted Democratic. In 2020, Biden won four of them, including Williamson, Hays, Fort Bend ,and Tarrant.\(^{63}\) The “Red Wall” includes the rest of the state, except for the border region, which was solidly Trump country and where he won by 1.7 million votes.\(^{64}\) As Senator Cruz remarked about his own race, “Historically, the cities have been bright blue and surrounded by bright red doughnuts of Republican suburban voters. What happened in 2018 is that those bright red doughnuts went purple—not blue, but purple.”\(^{65}\)

Diversity and the Hispanic Surprise

As noted earlier in the chapter, data indicated that eightynine percent of Black voters supported President Biden. In the 2020 election, sixty-three percent of Asian Americans also supported President Biden, a group that traditionally votes Republican.The border counties were the big surprise. Biden underperformed in these twenty eight counties. He won with just over 150,000 more votes than Trump but with only seventeen percentage points. In 2016, Clinton won with thirty-three percentage votes.\(^{66}\)

In the November election, sixty-seven percent of the Hispanic voters supported President Biden. But, the Hispanic voter was not a given for Democrats. Former President Trump performed well in a number of heavily Hispanic populated counties in South Texas. While Zapata County was the only county that went Republican, in the ninety-five percent Hispanic Webb County the Republicans doubled their turnout.

These results have raised more questions than answers. How could a president who used racialized anti-Hispanic rhetoric and was so vocally anti-immigrant do so well in these counties? Ross Barrera, a retired U.S. Army colonel and chair of the Starr County Republican Party said it is a mistake to lump all Hispanics in one column. “It’s the national media that uses ‘Latino.’ It bundles us up with Florida, Doral, Miami. But those places are different than South Texas, and South Texas is different than Los Angeles. Here, people don’t say we’re Mexican American. We say we’re Tejanos.”\(^{67}\) They believe that the Trump campaign spoke to them as Tejanos— concerned about the oil and gas industry, gun rights, and abortion with positions more in line with the Republican Party. The chairman of the Republican Party of Texas, Allen West, recently addressed the Republican National Hispanic Assembly in February of 2021. He told the audience that the first and last places that he campaigned before the election was the Rio Grande Valley:

That’s what we did in the Rio Grande Valley. So, all of a sudden, you had counties that had never been red for 100 years. Because they heard that it’s not about defunding our police, it’s not about keeping away safety, security. It’s about making sure you have strong families. It’s about making sure you have better educational opportunities. It’s about making sure that you can be a victor, which is why people come to the United States of America through the front door, not the back door. Because they want to be a part of what I call the ‘equality of opportunity’ and not the ‘equality of outcomes.’”\(^{68}\)

To be sure, Trump still lost the statewide Hispanic vote by double digits, but things are changing in Texas and the Democrats can no longer count on their vote.

The Gender Gap

One change in particular is women. Latinas, for example, were much more likely to vote Democrat than Latino men. Fifty-nine percent of Latino men voted for Biden, but seventy-five percent of Latinas did.\(^{69}\) The gender gap is more pronounced among Whites, where White men overwhelmingly favor Republican candidates. But the smaller gap among White men and women in 2016 is better explained by urban vs. rural voters. In 2016 White women in urban areas were more likely to vote for Democratic candidates, a pattern that continued in 2018 and 2020. Age matters, too, with younger White and Hispanic voters, and urban voters generally, more likely to vote for Democratic candidates. The majority religion can influence state politics and seventy-seven percent of Texans say they are Christian. It does not matter whether you are a Democrat or Republican, both Democrats and Republicans say religion plays a role in politics. However, Evangelical White voters—whether male or female—are more likely to favor Republican candidates, especially if the voters live in rural areas. There could be change on the Texas horizon as the Catholic population grows and more people are moving to Texas from other states.

- Kevin McPherson and Bruce Wright, “Federal Funding in Texas,” Fiscal Notes, Texas Comptroller, https://comptroller.texas.gov/econom...ralfunding.php.

- Alexa Ura and Connie Hanzhang Jin, “Texas Gained Almost Nine Hispanic Residents for Every Additional White Resident Last Year,” Texas Tribune, June 20, 2019, exastribune.org/2019/06/20/texas-hispanic-population-pace-surpass-white-residents/.

- Heather Leighton, “1860 Census Map Shows Distribution of Slaves in the Houston Area, Southern States,” Chron. Mar. 21, 2018, https://www.chron.com/news/houstonte...es12769865.php.

- Tomas Kassahun, “Texas Has the Most Black Voters of All the States, So This Voting Initiative Aims to Ensure all of these Voice Are Heard,” Blavity: News, July 27, 2020, https://blavity.com/texas-has-the-mo...o-this-voting- Chapter 1: Political Culture and People 67 initiative-aims-to-ensure-all-of-these-voices-areheard?category1=politics&category2=news.

- Jakob Rodriguez, “Here’s How Texans Voted in the 2020 Election by Age, Race and more, according to AP’s Vote Cast,” KSAT.com, Nov. 3, 2020, https://www.ksat.com/news/local/2020...d-in-the-2020- election-by-age-race-and-more-according-to-aps-votecast/.

- “Percent Voting by Age, Gender, Educational Attainment, Race, and Family Income: November 2020 Presidential Election,” The Texas Politics Project, https://texaspolitics.utexas.edu/ARC.../0302_02/DEMOG RAPHICS.HTML.

- “Texas Democratic Party, Powered by People, and Coalition of Black Democrats Announce New, Expansive Joint Black Voter Outreach Program,” Texas Democrats, June 27, 2020, https://www.texasdemocrats.org/media...reach-program/.

- “Percent Voting: November 2020 Presidential Election,” https://texaspolitics.utexas.edu/ARC.../0302_02/DEMOG RAPHICS.HTML

- “Texas Exit Polls: How Different Groups Voted,” New York Times, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/...lls-texas.html; https://www.washingtonpost.com/elect...as-exit-polls/

- Alex Samuels, “Why Asian American Voters in Texas May Hold Outsized Importance in Key Races This Year,” The Texas Tribune, Oct. 22, 2020.\

- Mirabeau B. Lamar, Speech to the Texas Congress, December 20, 1838, House Journal, Third Congress / “Native American Relations in Texas,” Texas State Library and Archives Commission, https://www.tsl.texas.gov/exhibits/i...peech1838.html; Texas' Second President Calls for the Expulsion or Extermination of the Republic's Indians,” Digital History, https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/di...id=3&psid=3667.

- Mirabeau B. Lamar to John Linney and all other Chiefs and Headmen of the Shawnee (letter), May 1839, Texas Indian Papers , vol. 1, no. 35 / “Native American Relations in Texas,” Texas State Library and Archives Commission, https://www.tsl.texas.gov/exhibits/i...ey-1839-1.html; “Texas's Second President Denounces the Cherokees for Conspiring with Mexico,” https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/di...id=3&psid=3668.

- “American Indians in Texas,” Texas Almanac 2020–2021 (Austin: Texas State Historical Society, 2019), https://texasalmanac.com/topics/cult...merican-indian.

- Nataly Keomoungkhoun, “What Happened to Native American Tribes That Once Existed in North Texas?” Dallas Morning News, Sept. 9, 2020, https://www.dallasnews.com/news/curi...-investigates/.

- Keomoungkhoun, “Native American Tribes in North Texas?” https://www.dallasnews.com/news/curi...-investigates/

- Trinady Joslin, “Native American Tribes in Texas Rally to Increase Voter Turnout,” Texas Tribune, Sept. 25, 2020, https://www.texastribune.org/2020/09...voter-turnout/

- Joslin, “Native Americans Increase Voter Turnout,” https://www.texastribune.org/2020/09...voter-turnout/.

- Olga Garza, David Green, Spencer Grubbs and Shannon Halbrook, “Young Texans: Demographic Overview,” Fiscal Notes, Texas Comptroller, Feb. 2020, https://comptroller.texas.gov/econom...feb/texans.php.

- Texas Demographics, American Community Survey 2015, https://gov.texas.gov/uploads/files/...pdate_2016.pdf.

- Frank Holmes and Great Speculations, “6 Reasons Why Texas Trumps All Other U.S. Economies,” Forbes, Oct. 23, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/greatsp...h=11fa630158be.

- “Texas 2019,” Talk Poverty, Center for American Progress,

- J.C. Dwyer, “Hunger in Texas Doubles During the Pandemic,” Feeding Texas, July 13, 2020, http://www.feedingtexas.org/texas-hu...nce,well%20as% 20families%20with%20children; Texas Workforce Commission, “Texas Workforce Commission Committed to Help Texans Find Work, Training and Resources,” May 22, 2020, https://www.twc.texas.gov/news/texas...te-128-percent.

- John W. Storey, “Religion,” Texas State Historical Association Handbook of Texas, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/religion.

- John Storey, “Spiritual Awakening: The State’s Religious History Is as Diverse as Its People,” Authentic Texas, https://authentictexas.com/spiritual-awakening/.

- Julie Fine, “Beyond Belief: Faith in Texas: The Intersection of Religion and Politics,” 5 NBC DFW, Apr. 19, 2017, https://www.nbcdfw.com/news/local/be...olitics/17106/.

- “Bridging the Gap Between Educational Attainment and Workforce Demands,” Red Flags, Shaping Our Workforce, https://texas2036.org/education-workforce/

- Lara Korte, “Report Shows 280,000 Texans Returned to College after ‘Stopping Out’,” Statesman, Nov. 1, 2019, https://www.statesman.com/news/20191...pping-outrsquo.

- Russel Falcon, “Texas is one of the most uneducated states in the U.S., study says,” KXAN, Jan 20, 2020, https://www.kxan.com/news/education/...-s-study-says/; Adam McCann, “Most and Least Educated Cities in America,” WalletHub, July 20.2020, https://wallethub.com/edu/e/most-and...ed-cities/6656

- “Texas Has Largest Gender Gap in Education,” Texas Community College Association (TCCA), https://www.tccta.org/2018/01/30/tex...-in-education/; Adam McCann, “Most & Least Educated Cities in America,” WalletHub, July 20.2020, https://wallethub.com/edu/e/most-and...ed-cities/6656.

- Aliyya Swaby, “Texas Will Require Students to Take the STAAR Test in Person,” Texas Tribune, Jan. 29, 2021, https://www.texastribune.org/2021/01...est-in-person/.

- Aliyya Swaby, “Many Texas Students Can Skip STAAR Tests This Year, but High Schoolers Might Have to Show Up to Graduate,” Texas Tribune, Feb. 12, 2021.

- Lloyd Potter, “2018 Estimated Population of Texas, Its Counties, and Places,” Texas Demographic Center, https://demographics.texas.gov/data/tpepp/estimates/.

- Alexu Ura and Carla Astudillo, “In 2021, White Men Are Still Overrepresented in the Texas Legislature,” Texas Tribune, Jan. 11, 2021, https://apps.texastribune.org/featur...epresentation/.

- Austin Capitol Advisors, “Texas Triangle,” https://www.austincapitaladvisors.com/texas-triangle.

- Amal Ahmed, “Millennials and Gen Zers are Breaking Voter Turnout Records in Texas,” Texas Observer, Nov. 2, 2020, https://www.texasobserver.org/young-voterstexas-2020/.

- Mandi Cai, Matthew Watkins, Anna Novak, and Darla Cameron, “In Texas, Biden’s Urban Wins Couldn’t Offset Trump’s Millions of Votes in Rural, Red Counties,” Texas Tribune, Nov. 6, 2020, https://www.texastribune.org/2020/11...suburban-city/.

- Cai, et al., “Urban Couldn’t Offset Rural,” https://www.texastribune.org/2020/11...-suburbancity/

- Cai, et al., “Urban Couldn’t Offset Rural,” https://www.texastribune.org/2020/11...-suburbancity/.

- Cai, et al., “Urban Couldn’t Offset Rural,” https://www.texastribune.org/2020/11...-suburbancity/.

- Robert Costa and Robert Moore, “Take Texas Seriously: GOP Anxiety Spikes After Retirements, Democratic Gains,” Washington Post, Aug. 2, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/polit...4b8-11e9-8949- 5f36ff92706e_story.html.

- Cai, et al., “Urban Couldn’t Offset Rural,” https://www.texastribune.org/2020/11...-suburbancity/.

- Jack Herrera, “Trump Didn’t Win the Latino Vote in Texas. He won the Tejano Vote,” Politico, Nov. 17, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/magazi...tejanos-437027

- Stewart Doreen, “West: Republican Party Already Share Principles with Hispanics,” Midland Reporter Telegram, Feb. 11, 2021, https://www.mrt.com/insider/article/...s-15944741.php.

- Celeste Montoya, “What conclusions can we draw about the Hispanic vote in 2020?,” Fortune, Nov. 10, 2020, https://fortune.com/2020/11/10/hispa...umpbiden-2020/.